A Plan to Close Guantánamo and End the Military Commissions Submitted to the Transition Team of President-Elect Obama From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Finale Des Délégations Final List of Delegations Lista Final De Delegaciones

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (11 juin 2014) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 103e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (11 June2014) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 103nd Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (11 de junio de 2014) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 103.a reunión, Ginebra 2014 Workers' Delegate Afghanistan Afganistán SHABRANG, Mohammad Dauod, Mr, Fisrt Deputy, National Employer Union. Minister attending the Conference AFZALI, Amena, Mrs, Minister of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled (MoLSAMD). Afrique du Sud South Africa Persons accompanying the Minister Sudáfrica ZAHIDI, Abdul Qayoum, Mr, Director, Administration, MoLSAMD. Minister attending the Conference TARZI, Nanguyalai, Mr, Ambassador, Permanent OLIPHANT, Mildred Nelisiwe, Mrs, Minister of Labour. Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva. Persons accompanying the Minister Government Delegates OLIPHANT, Matthew, Mr, Ministry of Labour. HAMRAH, Hessamuddin, Mr, Deputy Minister, HERBERT, Mkhize, Mr, Advisor to the Minister, Ministry MoLSAMD. of Labour. NIRU, Khair Mohammad, Mr, Director-General, SALUSALU, Pamella, Ms, Private Secretary, Ministry of Manpower and Labour Arrangement, MoLSAMD. Labour. PELA, Mokgadi, Mr, Director Communications, Ministry Advisers and substitute delegates of Labour. OMAR, Azizullah, Mr, Counsellor, Permanent Mission, MINTY, Abdul Samad, Mr, Ambassador, Permanent Geneva. Representative, Permanent Mission, -

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Forensic Mental Health Evaluations in the Guantánamo Military Commissions System: an Analysis of All Detainee Cases from Inception to 2018 T ⁎ Neil Krishan Aggarwal

International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 64 (2019) 34–39 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Law and Psychiatry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijlawpsy Forensic mental health evaluations in the Guantánamo military commissions system: An analysis of all detainee cases from inception to 2018 T ⁎ Neil Krishan Aggarwal Clinical Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, Committee on Global Thought, Columbia University, New York State Psychiatric Institute, United States ABSTRACT Even though the Bush Administration opened the Guantánamo Bay detention facility in 2002 in response to the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, little remains known about how forensic mental health evaluations relate to the process of detainees who are charged before military commissions. This article discusses the laws governing Guantánamo's military commissions system and mental health evaluations. Notably, the US government initially treated detaineesas“unlawful enemy combatants” who were not protected under the US Constitution and the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Forms of Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, allowing for the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques.” In subsequent legal documents, however, the US government has excluded evidence obtained through torture, as defined by the US Constitution and the United Nations Convention Against Torture. Using open-source document analysis, this article describes the reasons and outcomes of all forensic mental health evaluations from Guantánamo's opening to 2018. Only thirty of 779 detainees (~3.85%) have ever had charges referred against them to the military commissions, and only nine detainees (~1.16%) have ever received forensic mental health evaluations pertaining to their case. -

SALIM AHMED HAMDAN, Petitioner, V. UNITED STATES of AMERICA

USCA Case #11-1257 Document #1362775 Filed: 03/08/2012 Page 1 of 65 [Oral Argument Scheduled for May 3, 2012] No. 11-1257 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA SALIM AHMED HAMDAN, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. Appeal From The Court Of Military Commission Review (Case No. CMCR-09-0002) REPLY BRIEF OF PETITIONER SALIM AHMED HAMDAN Adam Thurschwell Harry H. Schneider, Jr. Jahn Olson, USMC Joseph M. McMillan OFFICE OF THE CHIEF DEFENSE Charles C. Sipos COUNSEL MILITARY COMMISSIONS Rebecca S. Engrav 1099 14th Street NW Angela R. Martinez Box 37 (Ste. 2000E) Abha Khanna Washington, D.C. 20006 PERKINS COIE LLP Telephone: 202.588.0437 1201 Third Avenue, Suite 4800 Seattle, WA 98101-3099 Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant Telephone: 206.359.8000 SALIM AHMED HAMDAN Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant SALIM AHMED HAMDAN USCA Case #11-1257 Document #1362775 Filed: 03/08/2012 Page 2 of 65 CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES The Certificate as to Parties, Rulings, and Related Cases is set forth in Petitioner-Appellant Salim Ahmed Hamdan’s Principal Brief filed on November 15, 2011, and is hereby incorporated by reference. DATED: March 8, 2012 By: /s/ Charles C. Sipos One of the attorneys for Salim Ahmed Hamdan -i- USCA Case #11-1257 Document #1362775 Filed: 03/08/2012 Page 3 of 65 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES.........................................................................................................i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES..................................................................... iv GLOSSARY OF TERMS .......................................................................... xi SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT.............................................................................................. 3 I. MST Is Not Triable by Military Commission ....................... -

Table of Contents

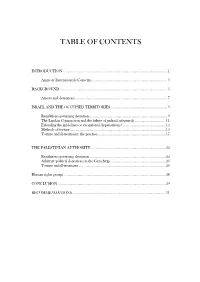

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

Unclassified//For Public Release Unclassified//For Public Release

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR PUBLIC RELEASE --SESR-Efll-N0F0RN- Final Dispositions as of January 22, 2010 Guantanamo Review Dispositions Country ISN Name Decision of Origin AF 4 Abdul Haq Wasiq Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 6 Mullah Norullah Noori Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 7 Mullah Mohammed Fazl Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 560 Haji Wali Muhammed Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war, subject to further review by the Principals prior to the detainee's transfer to a detention facility in the United States. AF 579 Khairullah Said Wali Khairkhwa Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 753 Abdul Sahir Referred for prosecution. AF 762 Obaidullah Referred for prosecution. AF 782 Awai Gui Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 832 Mohammad Nabi Omari Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 850 Mohammed Hashim Transfer to a country outside the United States that will implement appropriate security measures. AF 899 Shawali Khan Transfer to • subject to appropriate security measures. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

David Hicks, Mamdouh Habib and the Limits of Australian Citizenship

9/17/2015 b o r d e r l a n d s ejournal limits of australian citizenship vol 2 no 3 contents VOLUME 2 NUMBER 3, 2003 David Hicks, Mamdouh Habib and the limits of Australian Citizenship Binoy Kampmark University of Queensland I will continue to take an interest in the wellbeing of Mr Hicks as an Australian citizen to ensure that he is being treated humanely. Alexander Downer, Answer to Question on notice, 18 March 2003. 1. Citizenship is delivered in a brown paper bag at Australian ceremonies. You apply beforehand, and, if lucky, you are asked to attend a ceremony, where you are invited to take an oath (whether to God or otherwise), and witness the spectacle of having citizenship thrust upon you. ‘There has never been a better time to become an Australian citizen’ is marked on the package, which is signed by the Immigration Minister. Brown bags signify this entire process: we await the displays, the cameo aboriginal troupe intent on welcoming the naturalised citizen with a fire ceremony that misfires (or never fires), a lady with a speech impediment who deputises for the minister for Citizenship, and the various tiers of government expounding the virtues of civic responsibility. In short, the entire ceremony is a generous selfmocking; it is citizenship as comedy, a display of cultural symbols that are easily interchanged and shifted. The mocking of citizenship lies at the centre of Australia’s discourse on what it means to be an Australian citizen. It is parodic; it does not take itself seriously, which, some might argue, is its great strength. -

Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law — Volume 18, 2015 Correspondents’ Reports

YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW — VOLUME 18, 2015 CORRESPONDENTS’ REPORTS 1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Overview – United States Enforcement of International Humanitarian Law ............................ 1 Cases – United States Federal Court .......................................................................................... 3 Cases – United States Military Courts – Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (CAAF) ...... 4 Cases — United States Military Courts – United States Army ................................................. 4 Cases — United States Military Courts – United States Marine Corps .................................... 5 Issues — United States Department of Defense ........................................................................ 6 Issues — United States Army .................................................................................................... 8 Issues —United States Navy .................................................................................................... 11 Issues — United States Marine Corps ..................................................................................... 12 Overview – United States Detention Practice .......................................................................... 12 Detainee Challenges – United States District Court ................................................................ 13 US Military Commission Appeals ........................................................................................... 16 Court of Appeals for the -

Technology and Engineering International Journal of Recent

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering ISSN : 2277 - 3878 Website: www.ijrte.org Volume-8 Issue-2S6, JULY 2019 Published by: Blue Eyes Intelligence Engineering and Sciences Publication d E a n n g y i n g o e l e o r i n n h g c e T t n e c Ijrt e e E R X I N P n f L O I O t T R A o e I V N O l G N r IN n a a n r t i u o o n J a l www.ijrte.org Exploring Innovation Editor-In-Chief Chair Dr. Shiv Kumar Ph.D. (CSE), M.Tech. (IT, Honors), B.Tech. (IT), Senior Member of IEEE Blue Eyes Intelligence Engineering & Sciences Publication, Bhopal (M.P.), India. Associated Editor-In-Chief Chair Prof. MPS Chawla Member of IEEE, Professor-Incharge (head)-Library, Associate Professor in Electrical Engineering, G.S. Institute of Technology & Science Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India, Chairman, IEEE MP Sub-Section, India Dr. Vinod Kumar Singh Associate Professor and Head, Department of Electrical Engineering, S.R.Group of Institutions, Jhansi (U.P.), India Dr. Rachana Dubey Ph.D.(CSE), MTech(CSE), B.E(CSE) Professor & Head, Department of Computer Science & Engineering, Lakshmi Narain College of Technology Excellence (LNCTE), Bhopal (M.P.), India Associated Editor-In-Chief Members Dr. Hai Shanker Hota Ph.D. (CSE), MCA, MSc (Mathematics) Professor & Head, Department of CS, Bilaspur University, Bilaspur (C.G.), India Dr. Gamal Abd El-Nasser Ahmed Mohamed Said Ph.D(CSE), MS(CSE), BSc(EE) Department of Computer and Information Technology , Port Training Institute, Arab Academy for Science ,Technology and Maritime Transport, Egypt Dr. -

CTC Sentinel 4

JULY 2011 . VOL 4 . ISSUE 7 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC SentineL OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents The JRTN Movement and Iraq’s FEATURE ARTICLE 1 The JRTN Movement and Iraq’s Next Insurgency Next Insurgency By Michael Knights By Michael Knights REPORTS 6 Anwar al-`Awlaqi’s Disciples: Three Case Studies By Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens 10 Will Al-Qa`ida and Al-Shabab Formally Merge? By Leah Farrall 12 The Somali Diaspora: A Key Counterterrorism Ally By Major Josh Richardson 15 David Hicks’ Memoir: A Deceptive Account of One Man’s Journey with Al-Qa`ida By Ken Ward 17 Hizb al-Tahrir: A New Threat to the Pakistan Army? By Arif Jamal 20 The Significance of Fazal Saeed’s Defection from the Pakistani Taliban By Daud Khattak JRTN leader Izzat Ibrahim al-Duri, seen here in 1999. - Photo by Salah Malkawi/Getty Images 22 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity he stabilization of iraq This article argues that one driver for 24 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts has become wedged on a the ongoing resilience, or even revival, plateau, beyond which further of Sunni militancy is the growing improvement will be a slow influence of the Jaysh Rijal al-Tariq al- Tprocess. According to incident metrics Naqshabandi (JRTN) movement, which compiled by Olive Group, the average has successfully tapped into Sunni Arab monthly number of insurgent attacks fear of Iraq’s Shi`a-led government and between January and June 2011 was the country’s Kurdish population, while 380.1 The incident count in January offering an authentic Iraqi alternate to About the CTC Sentinel was 376, indicating that incident levels al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI). -

True and False Confessions: the Efficacy of Torture and Brutal

Chapter 7 True and False Confessions The Efficacy of Torture and Brutal Interrogations Central to the debate on the use of “enhanced” interrogation techniques is the question of whether those techniques are effective in gaining intelligence. If the techniques are the only way to get actionable intelligence that prevents terrorist attacks, their use presents a moral dilemma for some. On the other hand, if brutality does not produce useful intelligence — that is, it is not better at getting information than other methods — the debate is moot. This chapter focuses on the effectiveness of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation technique program. There are far fewer people who defend brutal interrogations by the military. Most of the military’s mistreatment of captives was not authorized in detail at high levels, and some was entirely unauthorized. Many military captives were either foot soldiers or were entirely innocent, and had no valuable intelligence to reveal. Many of the perpetrators of abuse in the military were young interrogators with limited training and experience, or were not interrogators at all. The officials who authorized the CIA’s interrogation program have consistently maintained that it produced useful intelligence, led to the capture of terrorist suspects, disrupted terrorist attacks, and saved American lives. Vice President Dick Cheney, in a 2009 speech, stated that the enhanced interrogation of captives “prevented the violent death of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of innocent people.” President George W. Bush similarly stated in his memoirs that “[t]he CIA interrogation program saved lives,” and “helped break up plots to attack military and diplomatic facilities abroad, Heathrow Airport and Canary Wharf in London, and multiple targets in the United States.” John Brennan, President Obama’s recent nominee for CIA director, said, of the CIA’s program in a televised interview in 2007, “[t]here [has] been a lot of information that has come out from these interrogation procedures.