Walking and the Reinvention of Space by Robert J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

WINTER 2013 You spoke … We listened For the last year, many of you have asked us numerous times for high-resolution audio downloads using Direct Stream Digital (DSD). Well, after countless hours of research and development, we’re thrilled to announce our new high-resolution service www.superhirez.com. Acoustic Sounds’ new music download service debuts with a selection of mainstream audiophile music using the most advanced audio technology available…DSD. It’s the same digital technology used to produce SACDs and to our ears, it most closely replicates the analog experience. They’re audio files for audiophiles. Of course, we’ll also offer audio downloads in other high-resolution PCM formats. We all like to listen to music. But when Acoustic Sounds’ customers speak, we really listen. Call The Professionals contact our experts for equipment and software guidance RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT RECOMMENDED SOFTWARE Windows & Mac Mac Only Chord Electronics Limited Mytek Chordette QuteHD Stereo 192-DSD-DAC Preamp Version Ultra-High Res DAC Mac Only Windows Only Teac Playback Designs UD-501 PCM & DSD USB DAC Music Playback System MPS-5 superhirez.com | acousticsounds.com | 800.716.3553 ACOUSTIC SOUNDS FEATURED STORIES 02 Super HiRez: The Story More big news! 04 Supre HiRez: Featured Digital Audio Thanks to such support from so many great customers, we’ve been able to use this space in our cata- 08 RCA Living Stereo from logs to regularly announce exciting developments. We’re growing – in size and scope – all possible Analogue Productions because of your business. I told you not too long ago about our move from 6,000 square feet to 18,000 10 A Tribute To Clark Williams square feet. -

K-2 ELA Handout

COSA Common Core State Standards Regional Series “Reading and Writing in the Classroom” A Statewide Regional Series for District and School Leaders of CCSS Elementary (K-2) English Language Arts Session Locations: April 14, 2014 – Eagle Crest Resort, Redmond, OR April 28, 2014 – Linn County Expo Center, Albany, OR May 6, 2014 - Convention Center, Pendleton, OR ELA Presenter: Jon Schuhl, SMc Curriculum, [email protected] Goals of CCSS Reading and Writing in the Classroom . U.S. students will become more competitive with A+ countries. Colleges will have less remediation for incoming students. Students across the country will have standards that are of equal rigor. Allows for development of common Jon Schuhl assessments and teaching materials. SMc Curriculum Spring 2014 The Standards Define: The Standards Do NOT Define: . what is most essential . how teachers should teach . grade level expectations . all that can or should be taught . what students are expected to know and be able . the nature of advanced work to do . intervention methods or materials . cross-disciplinary literacy skills . the full range of supports for English learners . mathematical habits of mind and students with special needs ELA Features ELA Features Reading Writing: Text types, responding to reading, and research . Balance of literature and informational texts . Text complexity and growth of comprehension . Writing arguments/opinions . The reading standards place equal emphasis on . Writing informative/explanatory texts the sophistication of what students read and the . Writing narratives skill with which they read. Strong and growing across-the-curriculum emphasis on students writing arguments and informative/explanatory texts 1 ELA Features ELA Features Language: Conventions (grammar), effective use, Speaking and Listening: Flexible communication and vocabulary and collaboration . -

Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Listening for the Cosmic Other: Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age Paige Zalman West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Zalman, Paige, "Listening for the Cosmic Other: Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3797. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3797 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Listening for the Cosmic Other: Postcolonial Approaches to Music in the Space Age” Paige Zalman Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Musicology Travis Stimeling, Ph.D., -

Locating the Astronaut Body in Space

Wesleyan University The Honors College Locating the Astronaut Body in Space by Rachel Quinn Fischhoff Class of 2008 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Dance and American Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2008 Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Astronaut Body in Freefall 5 Chapter 2: The Lunar Stage 37 Chapter 3: How to Make Two Dances 59 Conclusion 77 Selected Primary Sources 80 Bibliography 83 Acknowledgements Thank you Rachel Hirsch, Martha Armstrong Gray, Ted Munter and Moses Rifkin for first teaching me to learn all things in all ways. I would like to thank Nicole Stanton for her unwavering support throughout this process, the faculty of the Dance and American Studies Departments for helping me become the choreographer, dancer, and thinker I am today, and of course my fellow majors, who have never stopped teaching and inspiring me. To the toothbrush owners and dinner patrons of 43A Home Avenue, thank you. Kathleen, David, and Martha Fischhoff, thank you for making all things possible. Introduction Even a cursory glance at contemporary media shows the vital place astronauts have come to occupy in the national imagination of the United States. Space Camp, located at 1 Tranquility Base in Huntsville, AL offers day and residential programs for children ages 7 to 18. The camp’s website also advertises programs designed for corporate groups, educators, and “Special Programs” for the visually impaired and hard of hearing. The space-related work of Hollywood icon Tom Hanks alone includes film (Apollo 13), a televised miniseries (From Earth to the Moon), an IMAX movie (Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D), and the forward to a recent popular science book (Andrew Chaikin’s A Man on the Moon). -

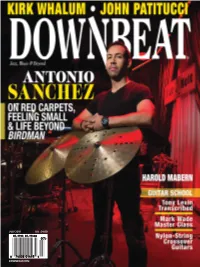

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 By

Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 By Elizabeth Sallinger M.M., Duquesne University, 2010 B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Paul R. Laird Roberta Freund Schwartz Bryan Kip Haaheim Colin Roust Leslie Bennett Date Defended: 5 December 2016 ii The dissertation committee for Elizabeth Sallinger certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 Chair: Paul R. Laird Date Approved: 5 December 2016 iii Abstract In 1968, the sound of the Broadway pit was forever changed with the rock ensemble that accompanied Hair. The musical backdrop for the show was appropriate for the countercultural subject matter, taking into account the popular genres of the time that were connected with such figures, and marrying them to other musical styles to help support the individual characters. Though popular styles had long been part of Broadway scores, it took more than a decade for rock to become a major influence in the commercial theater. The associations an audience had with rock music outside of a theater affected perception of the plot and characters in new ways and allowed for shows to be marketed toward younger demographics, expanding the audience base. Other shows contemporary to Hair began to include rock music and approaches as well; composers and orchestrators incorporated instruments such as electric guitar, bass, and synthesizer, amplification in the pit, and backup singers as components of their scores. -

6Th Grade Emergency Packet: Day 5

DAY 5 6th Grade Emergency Packet: Day 5 Reading & Writing: Directions: Complete the Reading & Writing MAP Review Packet. As you work through the packets, make sure you use the MAP Review Strategies listed below. READING 1. Read the questions before you read the passage. 2. Read the passage. Stop and think about what you are reading. 3. Read the questions and return to the text to select the best answer. 4. Think about the answer to the question before you start reading the answer choices. 5. Strike through any answers that you can rule out. 6. Always select the BEST answer. WRITING 1. Read the questions. 2. Think about the answer to the question before you start reading the answer choices. 3. Strike through any answers that you can rule out. 4. Always select the BEST answer. Math: Directions: Complete the Math MAP Review Packet. As you work through the packets, make sure you use the MAP Review Strategies listed below. MATH 1. Read the problems thoroughly. 2. Work out the problems to the side or on a separate piece of paper. 3. Strike through any answers that you can rule out. 4. Check your answer and make sure it makes sense in the problem. Day 5 of Emergency Packet: MAP Practice #5 Directions: Read the selection and answer questions 1-8 by circling the best answer. Feel free to mark up the text as you read to understand it completely. Then, answer the remaining writing questions 9-10. What Is a Spacesuit? By: David Hitt A spacesuit is much more than a set of clothes astronauts wear on spacewalks. -

LCSH Section W

W., D. (Fictitious character) Scott Reservoir (N.C.) Wa-Kan rōei shō (Scrolls) USE D. W. (Fictitious character) W. Kerr Scott Lake (N.C.) BT Calligraphy, Japanese W.12 (Military aircraft) Wilkesboro Reservoir (N.C.) Scrolls, Japanese USE Hansa Brandenburg W.12 (Military aircraft) William Kerr Scott Lake (N.C.) Wa-Kan rōeishū W.13 (Seaplane) William Kerr Scott Reservoir (N.C.) — Manuscripts USE Hansa Brandenburg W.13 (Seaplane) BT Reservoirs—North Carolina — — Facsimiles W.29 (Military aircraft) W Motors automobiles (Not Subd Geog) Wa-ko-ne-kin Creek (Utah) USE Hansa Brandenburg W.29 (Military aircraft) BT Automobiles USE Little Cottonwood Creek (Salt Lake County, W.A. Blount Building (Pensacola, Fla.) NT Lykan HyperSport automobile Utah) UF Blount Building (Pensacola, Fla.) W particles Wa language (May Subd Geog) BT Office buildings—Florida USE W bosons [PL4470] W Award W-platform cars BT Austroasiatic languages USE Prix W USE General Motors W-cars Wa maathi language W.B. Umstead State Park (N.C.) W. R. Holway Reservoir (Okla.) USE Mbugu language USE William B. Umstead State Park (N.C.) UF Chimney Rock Reservoir (Okla.) Wa no Na no Kuni W bosons Holway Reservoir (Okla.) USE Na no Kuni [QC793.5.B62-QC793.5.B629] BT Lakes—Oklahoma Wa-re-ru-za River (Kan.) UF W particles Reservoirs—Oklahoma USE Wakarusa River (Kan.) BT Bosons W. R. Motherwell Farmstead National Historic Park Wa wa erh W. Burling Cocks Memorial Race Course at Radnor (Sask.) USE Suo na Hunt (Malvern, Pa.) USE Motherwell Homestead National Historic Site Wa Zé Ma (Character set) UF Cocks Memorial Race Course at Radnor Hunt (Sask.) USE Amharic character sets (Data processing) (Malvern, Pa.) W. -

John Anthony Martinez CHARLES RAINEY Music Inc

RHYTHM INTENSIVE WORKSHOPS & SEMINARS DALLAS• NASHVILLE• LOS ANGELES• LONDON• ARGENTINA Rhythm Intensive is presented by Chuck Rainey & John Anthony Martinez CHARLES RAINEY Music Inc. (CRM) has been a long RhythmWho Intensive® has assembledWe a teamAre of prominent established ASCAP publishing professionals in the music industry. You won’t find more company. In 1980, CRM was passionate and inspired music educators anywhere. Our created to umbrella Chuck Rainey’s faculty includes Grammy Award winners, college professors, Co-Founders intellectual creative song rights. The legendary artists, and other gurus. company also directs and manages Chuck Rainey’s seminars and workshops throughout the global community of organized music. JOHN A. MARTINEZ Our missionWhat is to empower every localWe musician andDo music Founder and CEO of Fingerfoot Music maker. The skills developed in this program are invaluable for Productions (FMP), has been a member of musicians,producers, promoters and just about anyone else ASCAP since 1999 and is a voting member involved in music. of the National Association of Recording Arts and Sciences (the Grammys). FMP is a music production company based in the Dallas/ Fort Worth area of Texas (USA), providing A Program That’s Right for You! songwriting, music and audio services to the These clinics include all the topics from our syllabus. We will music and media industries. In 2004, FMP work together to develop a program tailored to suit the needs joined forces with Singapore based Electric of your organizations. Muse, consultants and developers of original music and multimedia. &Previous Guest Speakers Instructors John Anthony Martinez, Chuck Rainey, Thomas Dolby, Foley, Kevin Brandino, Jerry Jemmott, Vail Johnson, Rod Taylor, Victor Wooten, Bobby Vega, Ed Friedland, Chester Thompson, Dr. -

Title Format Released & His Orchestra South Pacific 12" 1958 Abdo

Title Format Released & His Orchestra South Pacific 12" 1958 Abdo, George & The Flames of Araby Orchestra Joy of Belly Dancing 12" 1975 Abdo, Geroge & The Flames of Araby Orchestra Art of Belly Dancing 12" 1973 Abney, Don, Jimmy Raney, Oscar Pettiford Music Minus One: A Rhythm Background Record For Any Musician Or Vocalist 12" 19NA Abrams, Muhal Richard Duet 12" 1981 Adderley, Cannonball The Cannonball Adderley Collection - Vol. 7: Cannonball in Europe 12" 1986 Somethin' Else 12" 1984 Domination 12" 1964 Cannonball Adderley Quintet In Chicago 12" 1959 African Waltz 12" 1961 Cannonball Takes Charge 12" 1959 Adderley, Cannonball Quintet Mercy, Mercy, Mercy! Live at 'The Club' 12" 19NA Ade, King Sunny Synchro System 12" 1983 Adelade Robbins Trio, Barbara Carroll Trio Lookin' for a Boy 12" 1958 Akiyosh, Toshiko-Lew Tabackin Big Band Road Time 12" 2 LPs 1976 Akiyoshi, Toshiko Lew Tabackin Big Band Tales of a Courtesan (Oirantan) 12" 1976 Albam, Manny Jazz Heritage: Jazz Greats of Our Time, Vol. 2 12" 1958 Alexander, Monty Alexander The Great 12" 1965 Facets 12" 1980 Monty Strikes Again: Monty Alexander Live In Germany 12" 1976 Duke Ellington Songbook 12" 1984 Spunky 12" 1965 Alexander, Monty & Ernest Ranglin Just Friends 12" 1981 Alexandria, Lorez The Band Swings Lorez Sings 12" 1988 Alexandria the Great 12" 1964 Lorez Sings Pres: A Tribute to Lester Young 12" 1987 For Swingers Only 12" 1963 Page 1 of 67 Title Format Released Alexandria, Lorez This Is Lorez 12" 1958 More Of The Great Lorez Alexandria 12" 1964 Allen, "Red" With Jack Teagarden And Kid Ory At Newport 12" 1982 Allen, Henry "Red" Giants Of Jazz 3 LP Box Set 1981 Ride, Red, Ride in Hi-Fi 12" 1957 Ridin' With Red 10" 1955 Allison, Mose V-8 Ford Blues 12" 1961 Back Country Suite 12" 1957 Western Man 12" 1971 Young Man Mose 12" 1958 Almeida, Laurindo with Bud Shank Brazilliance, Vol. -

Humberto Cane Record Collection, 1944-1998 700

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt596nc8sv No online items Finding Aid for the Humberto Cane Record Collection, 1944-1998 700 Processed by Maria Huacuja. Chicano Studies Research Center Library 2009 144 Haines Hall Box 951544 Los Angeles, California 90095-1544 [email protected] URL: http://chicano.ucla.edu Finding Aid for the Humberto 700 1 Cane Record Collection, 1944-1998 700 Contributing Institution: Chicano Studies Research Center Library Title: Humberto Cane Record Collection Creator: Cane, Humberto 1918 - 2000 Identifier/Call Number: 700 Physical Description: 7 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1944-1998 Abstract: This collection of LP records and audio cassette tapes is from the personal collection of Humberto Cane, Cuban born band leader, composer and arranger. COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library and Archive for paging information. Language of Material: English . Access Open for research. Acquisition Information This collection was given to the Chicano Studies Research Center by the UCLA music library. Deed is not on file here at the CSRC archive or at the UCLA music library. Provenance is inconclusive as of this writing. Biography Born in Matanzas, Cuba in 1918, multi-instrumentalist and band leader Humberto Cané organized one of the most highly regarded bands in the musical history of Mexico--specifically in the genres of Mambo and Cha Cha. In 1947 it was Cane's group that backed up Benny More in the recording of a now famous 10-inch LP at the outset of the popularization of Cha Cha and Mambo. -

CD 64 Motion Poet Peter Erskine Erskoman (P. Erskine) Not a Word (P

Prairie View A&M University Henry Music Library 5/23/2011 JAZZ CD 64 Motion Poet Peter Erskine Erskoman (P. Erskine) Not a Word (P. Erskine) Hero with a Thousand Faces (V. Mendoza) Dream Clock (J. Zawinul) Exit up Right (P. Erskine) A New Regalia (V. Mendoza) Boulez (V. Mendoza) The Mystery Man (B. Mintzer) In Walked Maya (P. Erskine) CD 65 Real Life Hits Gary Burton Quartet Syndrome (Carla Bley) The Beatles (John Scofield) Fleurette Africaine (Duke Ellington) Ladies in Mercedes (Steve Swallow) Real Life Hits (Carla Bley) I Need You Here (Makoto Ozone) Ivanushka Durachok (German Lukyanov) CD 66 Tachoir Vision (Marlene Tachoir) Jerry Tachoir The Woods The Trace Erica’s Dream Township Square Ville de la Baie Root 5th South Infraction Gibbiance A Child’s Game CD 68 All Pass By (Bill Molenhof) Bill Molenhof PB Island Stretch Motorcycle Boys All Pass By New York Showtune Precision An American Sound Wave Motion CD 69 In Any Language Arthur Lipner & The Any Language Band Some Uptown Hip-Hop (Arthur Lipner) Mr. Bubble (Lipner) In Any Language (Lipner) Reflection (Lipner) Second Wind (Lipner) City Soca (Lipner) Pramantha (Jack DeSalvo) Free Ride (Lipner) CD 70 Ten Degrees North 2 Dave Samuels White Nile (Dave Samuels) Ten Degrees North (Samuels) Real World (Julia Fernandez) Para Pastorius (Alex Acuna) Rendezvous (Samuels) Ivory Coast (Samuels) Walking on the Moon (Sting) Freetown (Samuels) Angel Falls (Samuels) Footpath (Samuels) CD 71 Marian McPartland Plays the Music of Mary Lou Williams Marian McPartland, piano Scratchin’ in the Gravel Lonely Moments What’s Your Story, Morning Glory? Easy Blues Threnody (A Lament) It’s a Grand Night for Swingin’ In the Land of Oo Bla Dee Dirge Blues Koolbonga Walkin’ and Swingin’ Cloudy My Blue Heaven Mary’s Waltz St.