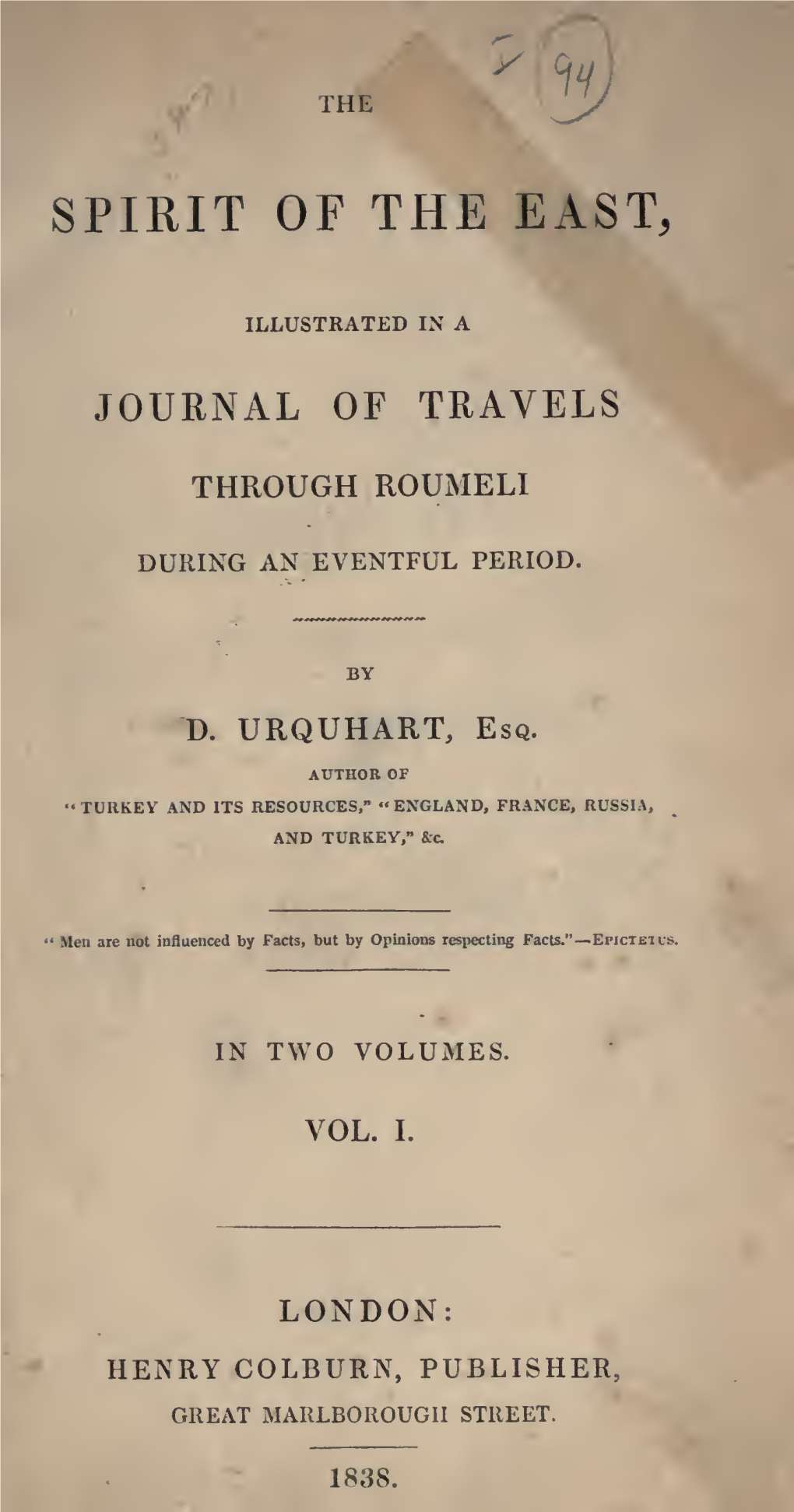

Spirit of the East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Is Ancient Greece?

WHERE IS GREECE? .Can we find Greece on the globe? .Which other countries are near Greece? Greece today .Greece is a small country in south east Europe. .Greece has an area of mainland, which is very mountainous, and hundreds of small islands dotted around in the Aegean and Ionian seas. .There are about 140 inhabited islands in Greece, but if you count every rocky outcrop, the total surges to about 3,000 . The largest island is Crete which is in the Mediterranean Sea. .The highest mountain in Greece is Mount Olympus (9,754 ft.), seat of the gods of Greek mythology. .The largest city and capital of Greece is Athens, with a population of over three million. .How big is Greece? Greece has a total area of 131.957 square kilometers (50,502 square miles). This includes 1,140 square kilometers of water and 130,800 square kilometers of land. .What is the flag of Greece like? The National Flag of Greece consists of four white and five blue alternating horizontal stripes, with a white cross on the upper inner corner. .Quick Facts about Greece .Capital: Athens .Population: 10.9 million .Population density (per sq km): 80 .Area: 131.957 sq km .Coordinates: 39 00 N, 22 00 E .Language: Greek .Major religion: Orthodox Christian .Currency: Euro Ancient Greece .The Ancient Greeks lived in mainland Greece and the Greek islands, but also in what is now Turkey, and in colonies scattered around the Mediterranean sea coast. .There were Greeks in Italy, Sicily, North Africa and as far west as France. -

The End of the Greek Millet in Istanbul

THE END OF THE GREEK MILLET IN ISTANBUL Stanford f. Shaw HE o cc u PAT I o N o F Is TAN B u L by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces following signature of the Armistice of Mondros (30 October 1918) was supposed to be a temporary measure, to last until the Peace Conference meeting in Paris decided on the finaldisposition of Tthat city as well as of the entire Ottoman Empire. From the start, however, the Christian religious and political leaders in Istanbul and elsewhere in what remained of the Empire, often encouraged by the occupation forces, stirred the Christian minorities to take advantage of the occupation to achieve greater political aims. Greek nationalists hoped that the occupation could be used to regain control of "Constantinople" and annex it to Greece along with Izmir and much of western Anatolia. From the first day of the armistice and occupation, the Greek Patriarch held daily meetings in churches throughout the city arousing his flock with passionate speeches, assuring those gathered that the long held dream of restoring Hellenism to "Constantinople" would be realized and that "Hagia Sophia" (Aya Sofya) would once again serve as a cathedral. The "Mavri Mira" nationalist society acted as its propaganda agency in Istanbul, with branches at Bursa and Band1rma in western Anatolia and at K1rkkilise (Kirklareli) and Tekirdag in Thrace. It received the support of the Greek Red Cross and Greek Refugees Society, whose activities were supposed to be limited to helping Greek refugees.• Broadsides were distributed announcing that Istanbul was being separated from the Ottoman Empire. -

Greek Independence Day Celebration

Comenius Project 2011 / 2012 The students, the teachers and language assistants in the Arco Iris School celebrated the Greek Liberation Day enjoying it for two week. The activities were as follows: 1) We have two posters to advertise this day, one to announce what is celebrated and the other to explain how they celebrate this day in Greece. Greek Independence Day Celebration The Greeks celebrate this day with military parades and celebrations throughout the country. Marching bands in traditional Greek military uniforms and Greek dancers in bright costumes move through the streets. Vendors serve roasted almonds, barbequed meat, baklava and lemonade to the flag waving crowds. The biggest parade is held in Athens. Additionally, the Greeks go to a special church service in honor of the religious events that took place on this day. Around the world, there are parades with a large Greek population. Independence Day in Greece On 25th March, Greece have their national day. They celebrate their independence from the Ottoman Empire in May 1832. The Ottoman Empire had been in control of Greece for more than 400 years. They celebrate on the 25th March because it is a holy day in Christianity and it was on this day that a priest waved a Greek flag as a symbol of revolution. This started the fight for independence. It lasted for many years. They celebrate the end of this war and the independence that followed every year on this day. 2) The students of 1st and 2nd, together with their teachers have done craft and related chips such as Greek flags, a slipper called "Tsaruchi" of his costume very representative for them and flags. -

ANCIENT GREECE? ▪Can We Find Greece on the Globe?

WHERE IS ANCIENT GREECE? ▪Can we find Greece on the globe? ▪Which other countries are near Greece? Greece today ▪Greece is a small country in south east Europe. ▪Greece has an area of mainland, which is very mountainous, and hundreds of small islands dotted around in the Aegean and Ionian seas. ▪There are about 140 inhabited islands in Greece, but if you count every rocky outcrop, the total surges to about 3,000 ▪ The largest island is Crete which is in the Mediterranean Sea. ▪The highest mountain in Greece is Mount Olympus (9,754 ft.), seat of the gods of Greek mythology. ▪The largest city and capital of Greece is Athens, with a population of over three million. ▪How big is Greece? Greece has a total area of 131.957 square kilometers (50,502 square miles). This includes 1,140 square kilometers of water and 130,800 square kilometers of land. ▪What is the flag of Greece like? The National Flag of Greece consists of four white and five blue alternating horizontal stripes, with a white cross on the upper inner corner. ▪Quick Facts about Greece ▪Capital: Athens ▪Population: 10.9 million ▪Population density (per sq km): 80 ▪Area: 131.957 sq km ▪Coordinates: 39 00 N, 22 00 E ▪Language: Greek ▪Major religion: Orthodox Christian ▪Currency: Euro Ancient Greece ▪The Ancient Greeks lived in mainland Greece and the Greek islands, but also in what is now Turkey, and in colonies scattered around the Mediterranean sea coast. ▪There were Greeks in Italy, Sicily, North Africa and as far west as France. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Ancient Greece

History/Geography- Ancient Greece- 6-week project- Summer Term 2 Children should complete this project over a 6-week period, with the advice that they spend 45 minutes per week working on this. The end goal is for children to be able to produce a piece of writing all about how Greece has changed. Lesson 1- An introduction to Ancient Greece Children should work through the powerpoint provided and see if they can identify Greece on a map. In their workbooks, children should list 3 places in Greece, remembering to focus on the spellings of proper nouns. They should then pick one of these places, research and write down 3 facts about this area. For example: Athens is famous for holding the Olympic Games. Lesson 2- Who were the Ancient Greeks? Children should read through the powerpoint about the Ancient Greeks. They should take notes about the Ancient Greek way of life. In their workbooks children should answer this question: How did the Ancient Greeks live? Children will need adult help to answer this, some sentence starters could be: Ancient Greeks were good at building, we know this because………………. Ancient Greek armies were strong………………………………………………. Children should aim to write at least 3 sentences in their workbooks, as they will be using this throughout their topic. Lesson 3- Greece now Using the powerpoint provided, children should look at the differences between Ancient Greece and the modern-day Greece. They should now fill in the worksheet provided, showing the differences between the two. Lesson 4/5- Greek travel agent challenge! Children now need to imagine that they are travel agents and should make a brochure persuading people to go on holiday to Greece. -

Powerpoint Guidance

Aim • To explore the geographical features of Greece. Success Criteria • Where in the World Is Greece? Greece is a country in Europe. It shares borders with Albania, Turkey, Macedonia and Bulgaria. Greece: The Facts Name: Greece Capital city: Athens Currency: Euro (€) Population: 11 million Language: Greek Average 50 – 121cm in the north Flag of Greece rainfall: 38 – 81cm in the south (Hellenic Republic) Greece: The Facts Greece is in southern Europe. It has a warmer climate than the UK. Greece Summer Winter Temperature Temperature Click to change between summer and winter temperatures. Coastline Greece has 8479 miles of coastline. In fact, no point is more than 85 kilometres from the coast. Use an atlas to find the location of these seas: Aegean Sea Mediterranean Sea Ionian Sea Aegean Sea Ionian Sea Mediterranean Sea ShowHide AnswersAnswers Islands There are over 2000 islands that make up the Greek nation. Around 170 of these islands are populated. If you counted every rocky outcrop, however, the number of islands would total more than 3000. Islands account for around 20% of the country’s land area. Crete is the largest of the Greek islands. Can you locate it? Have you been on holiday to Greece? Did you stay on one of the islands? Crete ShowHide AnswerAnswer Mainland Greece Greece is one of the most mountainous countries in Europe. In fact, there are no navigable rivers because it is so mountainous. In Greek mythology, Mount Olympus is said to be the seat of the Gods. Mount Olympus is the highest mountain in Greece. It measures 9754 feet high (3 kms). -

Tina Fey Hosts the Golden Globes Down to The

S o C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek- Americans N c v A weekly Greek-AMericAn PublicAtion www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 18, ISSUE 901 January 17-23, 2015 $1.50 Tina Fey Down to the Wire: New Democracy Cuts into SYRIZA’s Lead Hosts the Samaras Hopeful that Momentum Will Be Golden Enough for Reelection on January 25th ATHENS – With polls showing while elevating the anti-austerity the gap between the front-run - SYRIZA. Globes ning major opposition Coalition The latest opinion showed of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) and that New Democracy had closed his ruling New Democracy Con - the gap, that had been as high With Comic Pal servatives closing ahead of the as 3.2 percent, to 1.9 percent as Jan. 25 critical elections, Prime Samaras pounded home warn - Amy Poehler, Minister Antonis Samaras is still ings that a SYRIZA administra - hoping he can overtake his ri - tion –which has promised to Steals the Show vals. redo the Troika terms or walk At stake, he said, is the future away from the debt – could un - By Constantinos E. Scaros of the country. Samaras said the ravel the recovery, push Greece austerity measures he imposed out of the Eurozone and bring Elizabeth Stamatina Fey, bet - on orders of international financial catastrophe. ter known as Tina, whose Greek lenders – which he initially op - According to a nationwide ancestors include a survivor of posed – have worked and opinion poll conducted by Inter - the Chios Massacre of 1822, brought the country to the edge view on behalf of northern stood alongside her lifelong of a recovery from a crushing Greece's Vergina TV on a sample friend and fellow Saturday economic crisis even while cre - of 1,000 people, SYRIZA led with Night Live alumna Amy Poehler ating record unemployment and 28.3 percent but with New as the two comediennes hosted deep poverty while letting tax Democracy right behind at 26.4 the 2015 Golden Globe Awards cheats, politicians, and the rich percent. -

The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1820-1860

»OOM U üNviRsmr OFu om oti SEiATE HOUSE M,MET STRffif LOWDON WO* MU./ The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1 8 2 0 -1 8 6 0 Lucia Patrizio Gunning University College London, PhD Thesis, July 1997 Charles Thomas Newton and Dominic Ellis Colnaghi on horseback in Mitilene ProQuest Number: 10106684 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10106684 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 AOAOHÆC RCXAÎ k ÜNiVERSmf OF VDmCM gH^TE HOU^ / M A IH STTEEÎ t£riDOH WQÜ 3H I/ The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1820-1860 Lucia Patrizio Gunning University College London, PhD Thesis, July 1997 A bstract This thesis investigates the consular service in the Aegean from the final years of the Levant Company administration until 1860, a date that roughly coincides with the end of the British protectorate of the Ionian islands. The protectorate had made it necessary for the British Government to appoint consuls in the Aegean in order that they might look after the lonians. -

School Projects GREECE LITHUANIA POLAND

C O M E The four seasons and N the circle of I life U S School projects GREECE LITHUANIA POLAND May 2001 PORTUGAL THE NETHERLANDS Stella Lamprianou (www.digipass.gr) 1 The four seasons and the circle of life in Europe Gymnasium of Archagelos Archagelos Rhodes island GREECE MAY 2001 Stella Lamprianou (www.digipass.gr) 2 THIS MATERIAL WAS MADE BY Lamprianou Stella, English Teacher SPECIAL THANKS FOR THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO Gialelis Nikos, Greek Language Teacher Aidonidou Evi, Art Teacher Theodoridou Chrisana, German teacher PARTICIPANT PUPILS B CLASS 10. Lamprianou Maria 1. Argirou Dimitra 11. Makiari Dimitra 2. Ahiola Anna 12. Makiaris Nikolaos 3. Geronta Vasiliki 13. Mavriou Irene 4. Giasiranis Tsampikos 14. Dakas Tsampikos 5. Gogoulis Giannis 15. Ikouta Stella 6. Thoma Anthi 16. Paga Anthi 7. Kamma Anna 17. Panagiotas Michalis 8. Koliadi Natasa 18. Panagiotas Tsampikos 9. Koliou Stergoula 19. Pardalos Stefanos 10. Kontou Evi 20. Pardalou Tsampika 11. Louka Maria 21. PatsaiAnthi 12. Loukas Vasilis 22. Patsai Filitsa 13. Matsigou Irene 23. Peta Stamatia 14. Mavriou Tsampika 24. Pinnika Flora 15. Xetrihi Zoe 25. Portikala Natasa 16. Papanikolas Giorgos 26. Sarika Stella 17. Patsai Haroula 27. Serbis Grigoris 18. Tsakiris Savas 28. Skarpeti Katholiki 29. Spathas Antonis A CLASS 30. Tsakiris Iakovos 1. Afantenos Tsampikos 31. Fragou Maria 2. Gantaris Tsampikos 32. Handakari Maria 3. Giasirani Katerina 33. Hatzi Vagelitsa 4. Ikouta Hrisanthi 34. Hatzi Hrisoula 5. Koliou Efi 35. Hatzigeorgiou Eva 6. Koliou Nikolas 36. Hatzinikolas Panagiotis 7. Koliou Tsampikos 37. Psara Tsampika 8. Kontogiannou Tsampika 9. Kouros Nikitas Stella Lamprianou (www.digipass.gr) 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS 3 Participant teachers and pupils 4-5 Table of contents 6-10 Pupils’ paintings 11 Geophysical map of Greece 12 Political map of Greece 13 Rodos island 14-16 GREECE AT A GLANCE. -

Greek War of Independence (1821–1832) by Ioannis Zelepos

Greek War of Independence (1821–1832) by Ioannis Zelepos This article deals with developments leading up to, the unfolding of and the outcome of the Greek War of Independence which began in 1821, while focusing in particular on the international dimension of the conflict. Just as diaspora communities in western and central Europe who had been influenced by the French Revolution of 1789 had played a central role in the emergence of the Greek nationalist movement, the insurrection itself also quickly became an international media event throughout Europe. It was the European great powers who ultimately rescued the rebellion (which was hopelessly divided and which had actually failed militarily) through largescale intervention and who put the seal on Greek sovereignty in 1830/32. The emergence of Greece as a European project between great power politics and philhellenism had a profound effect on the further development of the country. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Nationalist Revolutionary Energy from the Late 18th Century Onward 2. Conditions on the Eve of the War of Independence 3. Start: The Rebellion in the Danubian Principalities (1821) 4. Escalation I: Insurrection in the Peloponnese, Central Greece and the Islands (1821) 1. Actors and Clientelist Structures 5. Escalation II: Nationalization of the Conflict in the Second Year of the War (1822) 1. Constitutional Crisis and Civil Wars of 1823/1824 6. Escalation III: Internationalization of the Conflict (1825–1827) 7. State Formation with Setbacks (1828–1832) 8. Greece as a European Project 9. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Literature 3. Notes Indices Citation Nationalist Revolutionary Energy from the Late 18th Century Onward The emergence of nationalist revolutionary energy in Greek-speaking milieus from the last decade of the 18th century has been documented.1 The Greek diaspora in central and western Europe provided the central impetus in this process, reflecting to a large degree the political upheavals of the period, which had been triggered by the French Revolution (➔ Media Link #ab) of 1789. -

Thucydides HISTORY of the PELOPONNESIAN WAR

Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR ■ HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvisori/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/00-index.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR:Index. Thucydides HISTORY OF THE PELOPONNESIAN WAR General Index ■ THE FIRST BOOK ■ THE SECOND BOOK ■ THE THIRD BOOK ■ THE FOURTH BOOK ■ THE FIFTH BOOK ■ THE SIXTH BOOK ■ THE SEVENTH BOOK ■ THE EIGHTH BOOK file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvisori/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/0-PeloponnesianWar.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 PELOPONNESIANWAR: THE FIRST BOOK, Index. THE FIRST BOOK Index CHAPTER I. The State of Greece from the earliest Times to the Commencement of the Peloponnesian War CHAPTER II. Causes of the War - The Affair of Epidamnus - The Affair of Potidaea CHAPTER III. Congress of the Peloponnesian Confederacy at Lacedaemon CHAPTER IV. From the end of the Persian to the beginning of the Peloponnesian War - The Progress from Supremacy to Empire CHAPTER V. Second Congress at Lacedaemon - Preparations for War and Diplomatic Skirmishes - Cylon - Pausanias - Themistocles file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvi...i/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/1-PeloponnesianWar0.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 PELOPONNESIANWAR: THE SECOND BOOK, Index. THE SECOND BOOK Index CHAPTER VI. Beginning of the Peloponnesian War - First Invasion of Attica - Funeral - Oration of Pericles CHAPTER VII. Second Year of the War - The Plague of Athens - Position and Policy of Pericles - Fall of Potidaea CHAPTER VIII. Third Year of the War - Investment of Plataea - Naval Victories of Phormio - Thracian Irruption into Macedonia under Sitalces file:///D|/Documenta%20Chatolica%20Omnia/99%20-%20Provvi...i/mbs%20Library/001%20-Da%20Fare/1-PeloponnesianWar1.htm2006-06-01 15:02:55 PELOPONNESIANWAR: THE THIRD BOOK, Index.