The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1820-1860

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Is Ancient Greece?

WHERE IS GREECE? .Can we find Greece on the globe? .Which other countries are near Greece? Greece today .Greece is a small country in south east Europe. .Greece has an area of mainland, which is very mountainous, and hundreds of small islands dotted around in the Aegean and Ionian seas. .There are about 140 inhabited islands in Greece, but if you count every rocky outcrop, the total surges to about 3,000 . The largest island is Crete which is in the Mediterranean Sea. .The highest mountain in Greece is Mount Olympus (9,754 ft.), seat of the gods of Greek mythology. .The largest city and capital of Greece is Athens, with a population of over three million. .How big is Greece? Greece has a total area of 131.957 square kilometers (50,502 square miles). This includes 1,140 square kilometers of water and 130,800 square kilometers of land. .What is the flag of Greece like? The National Flag of Greece consists of four white and five blue alternating horizontal stripes, with a white cross on the upper inner corner. .Quick Facts about Greece .Capital: Athens .Population: 10.9 million .Population density (per sq km): 80 .Area: 131.957 sq km .Coordinates: 39 00 N, 22 00 E .Language: Greek .Major religion: Orthodox Christian .Currency: Euro Ancient Greece .The Ancient Greeks lived in mainland Greece and the Greek islands, but also in what is now Turkey, and in colonies scattered around the Mediterranean sea coast. .There were Greeks in Italy, Sicily, North Africa and as far west as France. -

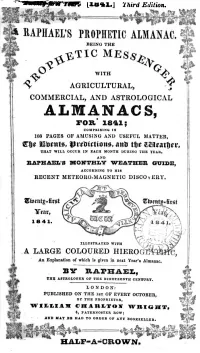

Raphael's Prophetic Almanac

Twenty - first Year . 1841 . ] Third Edition . & RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC SENGE . ELA BEING THE PROPHET ETIC MESSE WITH AGRICULTURAL , COMMERCIAL , AND ASTROLOGICAL ALMANACS , FOR ' 1841 ; COMPRISING IN 108 PAGES OF AMUSING AND USEFUL MATTER , The Events , Predictions , and the deather , THAT WILL OCCUR IN EACH MONTH DURING THE YEAR , AND RAPHAEL ' S MONTHLY WEATHER GUIDE , ACCORDING TO HIS RECENT METEORO - MAGNETIC DISCO v ERY . Twenty - first Twenty - first ¥ear , xids VCUAL 18 41 . V za ATIN W 184 1 . ILLUSTRATED WITH A LARGE COLOURED HIEROGLYPHIC , An Explanation of which is given in next Year ' s Almanac . BY RAPHAEL , ASTROLOGER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY . LONDON : PUBLISHED ON THE Ist OF EVERY OCTOBER , BY THE PROPRIETOR , WILLIAM CHARLTON WRIGHT . 4 , PATERNOSTER ROW ; AND MAY BE HAD TO ORDER OF ANY BOOKSELLER . HALF - A - OROWN . HUEROGLYPHIC FO TWENTY - FIRST ANNUAL NOTICE , 1841 . RAPHAEL continues to receive from all parts eulogistic ap proval of his labours . The sale last year mach increased , and RAPHAEL ' s industry has been prompted to make it still more useful and interesting . The uninitiated in the art of book - printing would be astonished were they to know the expense of getting out a work , small in appearance , but containing so many figures and calculations ; in truth , it is only the extensive circulation which RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC maintains which remune rates author and publisher . The work ( established twenty - one years ) requires much care and attention to understand it properly ; but , when this difficulty is conquered , our readers become ena . moured with the subject , fascinated with its contents , and recom . -

The End of the Greek Millet in Istanbul

THE END OF THE GREEK MILLET IN ISTANBUL Stanford f. Shaw HE o cc u PAT I o N o F Is TAN B u L by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces following signature of the Armistice of Mondros (30 October 1918) was supposed to be a temporary measure, to last until the Peace Conference meeting in Paris decided on the finaldisposition of Tthat city as well as of the entire Ottoman Empire. From the start, however, the Christian religious and political leaders in Istanbul and elsewhere in what remained of the Empire, often encouraged by the occupation forces, stirred the Christian minorities to take advantage of the occupation to achieve greater political aims. Greek nationalists hoped that the occupation could be used to regain control of "Constantinople" and annex it to Greece along with Izmir and much of western Anatolia. From the first day of the armistice and occupation, the Greek Patriarch held daily meetings in churches throughout the city arousing his flock with passionate speeches, assuring those gathered that the long held dream of restoring Hellenism to "Constantinople" would be realized and that "Hagia Sophia" (Aya Sofya) would once again serve as a cathedral. The "Mavri Mira" nationalist society acted as its propaganda agency in Istanbul, with branches at Bursa and Band1rma in western Anatolia and at K1rkkilise (Kirklareli) and Tekirdag in Thrace. It received the support of the Greek Red Cross and Greek Refugees Society, whose activities were supposed to be limited to helping Greek refugees.• Broadsides were distributed announcing that Istanbul was being separated from the Ottoman Empire. -

Greek Independence Day Celebration

Comenius Project 2011 / 2012 The students, the teachers and language assistants in the Arco Iris School celebrated the Greek Liberation Day enjoying it for two week. The activities were as follows: 1) We have two posters to advertise this day, one to announce what is celebrated and the other to explain how they celebrate this day in Greece. Greek Independence Day Celebration The Greeks celebrate this day with military parades and celebrations throughout the country. Marching bands in traditional Greek military uniforms and Greek dancers in bright costumes move through the streets. Vendors serve roasted almonds, barbequed meat, baklava and lemonade to the flag waving crowds. The biggest parade is held in Athens. Additionally, the Greeks go to a special church service in honor of the religious events that took place on this day. Around the world, there are parades with a large Greek population. Independence Day in Greece On 25th March, Greece have their national day. They celebrate their independence from the Ottoman Empire in May 1832. The Ottoman Empire had been in control of Greece for more than 400 years. They celebrate on the 25th March because it is a holy day in Christianity and it was on this day that a priest waved a Greek flag as a symbol of revolution. This started the fight for independence. It lasted for many years. They celebrate the end of this war and the independence that followed every year on this day. 2) The students of 1st and 2nd, together with their teachers have done craft and related chips such as Greek flags, a slipper called "Tsaruchi" of his costume very representative for them and flags. -

ANCIENT GREECE? ▪Can We Find Greece on the Globe?

WHERE IS ANCIENT GREECE? ▪Can we find Greece on the globe? ▪Which other countries are near Greece? Greece today ▪Greece is a small country in south east Europe. ▪Greece has an area of mainland, which is very mountainous, and hundreds of small islands dotted around in the Aegean and Ionian seas. ▪There are about 140 inhabited islands in Greece, but if you count every rocky outcrop, the total surges to about 3,000 ▪ The largest island is Crete which is in the Mediterranean Sea. ▪The highest mountain in Greece is Mount Olympus (9,754 ft.), seat of the gods of Greek mythology. ▪The largest city and capital of Greece is Athens, with a population of over three million. ▪How big is Greece? Greece has a total area of 131.957 square kilometers (50,502 square miles). This includes 1,140 square kilometers of water and 130,800 square kilometers of land. ▪What is the flag of Greece like? The National Flag of Greece consists of four white and five blue alternating horizontal stripes, with a white cross on the upper inner corner. ▪Quick Facts about Greece ▪Capital: Athens ▪Population: 10.9 million ▪Population density (per sq km): 80 ▪Area: 131.957 sq km ▪Coordinates: 39 00 N, 22 00 E ▪Language: Greek ▪Major religion: Orthodox Christian ▪Currency: Euro Ancient Greece ▪The Ancient Greeks lived in mainland Greece and the Greek islands, but also in what is now Turkey, and in colonies scattered around the Mediterranean sea coast. ▪There were Greeks in Italy, Sicily, North Africa and as far west as France. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Revista De Historia De América Número 15

THE CHILEAN FAILURE TO OBTAIN BRITISH RECOGNITION. 1823-1828 The year 1823 witnessed a significant modification of the attitude of the British Foreign Office toward Chile. Soon after coming into office in 1822 Canning took up the ques• tion of Hispanic America. He apparently believed it possible to gain Cabinet support for immediate recognition of the Hispanic American states. Confidently he offered media• tion to Spain, but without result. Many influences were at work to bring about closer Anglo-Chilean relations at this time. ln June, 1818, Com- modore Bowles of the Royal Navy wrote that the quantity of British trade with Chile made very desirable the appoint• ment of a commercial agent in that country,1 and sugges• tions of this type grew more frequent as time passed. In April, 1822, meetings were held by London merchants for the purpose of "maintaining" commercial intercourse with the Hispanic American nations,2 and Liverpool shipowners and merchants petitioned for recognition of the indepen• dence of those countries. Canning, supported by such evidence of public support, was able in 1823 to carry through the Cabinet his project 1 Bowles to Admiralty, 7 June, 1818 (Public Record Office, Ad• miralty 1/23, N° 84, secret); JosÉ PACÍFICO OTERO, Historia del liber• tador (4 vols.; Buenos Aires, 1932), II, pp. 432-433. 2 FREDERIC L. PAXSON, The independence of the South American republics, a stu y in recognition and foreign policy (Philadelphia, 1903), p. 203. 285 Derechos Reservados Citar fuente Instituto Panamericano de Geografia e Historia Charles W. Centner. R. H. A., Núm. 15 for the appointment of commercial agents to the South American republics. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Ancient Greece

History/Geography- Ancient Greece- 6-week project- Summer Term 2 Children should complete this project over a 6-week period, with the advice that they spend 45 minutes per week working on this. The end goal is for children to be able to produce a piece of writing all about how Greece has changed. Lesson 1- An introduction to Ancient Greece Children should work through the powerpoint provided and see if they can identify Greece on a map. In their workbooks, children should list 3 places in Greece, remembering to focus on the spellings of proper nouns. They should then pick one of these places, research and write down 3 facts about this area. For example: Athens is famous for holding the Olympic Games. Lesson 2- Who were the Ancient Greeks? Children should read through the powerpoint about the Ancient Greeks. They should take notes about the Ancient Greek way of life. In their workbooks children should answer this question: How did the Ancient Greeks live? Children will need adult help to answer this, some sentence starters could be: Ancient Greeks were good at building, we know this because………………. Ancient Greek armies were strong………………………………………………. Children should aim to write at least 3 sentences in their workbooks, as they will be using this throughout their topic. Lesson 3- Greece now Using the powerpoint provided, children should look at the differences between Ancient Greece and the modern-day Greece. They should now fill in the worksheet provided, showing the differences between the two. Lesson 4/5- Greek travel agent challenge! Children now need to imagine that they are travel agents and should make a brochure persuading people to go on holiday to Greece. -

Archaeology Among the Ruins: Photography and Antiquity in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Levant

Podcast transcript Archaeology Among the Ruins: Photography and Antiquity in mid-nineteenth-century Levant The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace Wednesday, 26 November 2014 Dr Amara Thornton, University College London Hello, this is a special Royal Collection Trust podcast on the extraordinary work of photographer Francis Bedford, who accompanied the Prince of Wales on his tour of the Middle East in 1862. In this podcast, Dr Amara Thornton from University College London gives a lecture written by Dr Debbie Challis on Bedford entitled ‘Archaeology Among the Ruins’ to an audience at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. Although Bedford’s work fits into a long Western tradition of picturing the Orient, during this period photography was becoming increasingly respected as a science. Dr Thornton will be exploring the effect photography had on the emerging science of archaeology. This is an enhanced podcast so make sure you look at the images when they appear on the screen of your device. [00:49] Dr Amara Thornton: Good afternoon everyone. It’s a pleasure to be here today. During the 19th century, what was understood by the Orient was basically defined by the geographical limits of the Ottoman Empire. British archaeological exploration took place in the Ottoman ruled lands around the Mediterranean. At the height of its power, from the 14th to the 17th centuries, the Ottoman Empire stretched from the edge of modern day Iran in the east across Turkey, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Greece and the Balkan states, to Hungary in the west. By the 1860s, part of what is now Greece was independent after the War of Independence in 1829, but the Balkan territories were a part of the Ottoman lands until 1878 and ostensibly most of North Africa, including Egypt, <Footer addr ess> were supplicant states. -

Powerpoint Guidance

Aim • To explore the geographical features of Greece. Success Criteria • Where in the World Is Greece? Greece is a country in Europe. It shares borders with Albania, Turkey, Macedonia and Bulgaria. Greece: The Facts Name: Greece Capital city: Athens Currency: Euro (€) Population: 11 million Language: Greek Average 50 – 121cm in the north Flag of Greece rainfall: 38 – 81cm in the south (Hellenic Republic) Greece: The Facts Greece is in southern Europe. It has a warmer climate than the UK. Greece Summer Winter Temperature Temperature Click to change between summer and winter temperatures. Coastline Greece has 8479 miles of coastline. In fact, no point is more than 85 kilometres from the coast. Use an atlas to find the location of these seas: Aegean Sea Mediterranean Sea Ionian Sea Aegean Sea Ionian Sea Mediterranean Sea ShowHide AnswersAnswers Islands There are over 2000 islands that make up the Greek nation. Around 170 of these islands are populated. If you counted every rocky outcrop, however, the number of islands would total more than 3000. Islands account for around 20% of the country’s land area. Crete is the largest of the Greek islands. Can you locate it? Have you been on holiday to Greece? Did you stay on one of the islands? Crete ShowHide AnswerAnswer Mainland Greece Greece is one of the most mountainous countries in Europe. In fact, there are no navigable rivers because it is so mountainous. In Greek mythology, Mount Olympus is said to be the seat of the Gods. Mount Olympus is the highest mountain in Greece. It measures 9754 feet high (3 kms). -

Homer, Troy and the Turks

4 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Uslu Homer, Troy and the Turks the and Troy Homer, Günay Uslu Homer, Troy and the Turks Heritage and Identity in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1870-1915 Homer, Troy and the Turks Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approach. Monographs or edited volumes critically interrogate the politics of heritage and dynamics of memory, as well as the theoretical implications of landscapes and mass violence, nationalism and ethnicity, heritage preservation and conservation, archaeology and (dark) tourism, diaspora and postcolonial memory, the power of aesthetics and the art of absence and forgetting, mourning and performative re-enactments in the present. Series Editors Rob van der Laarse and Ihab Saloul, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Editorial Board Patrizia Violi, University of Bologna, Italy Britt Baillie, Cambridge University, United Kingdom Michael Rothberg, University of Illinois, USA Marianne Hirsch, Columbia University, USA Frank van Vree, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Homer, Troy and the Turks Heritage and Identity in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1870-1915 Günay Uslu Amsterdam University Press This work is part of the Mosaic research programme financed by the Netherlands Organisa- tion for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover illustration: Frontispiece, Na’im Fraşeri, Ilyada: Eser-i Homer (Istanbul, 1303/1885-1886) Source: Kelder, Uslu and Șerifoğlu, Troy: City, Homer and Turkey Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Editor: Sam Herman Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 269 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 273 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462982697 nur 685 © Günay Uslu / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 All rights reserved.