Henry George Ward and Texas, 1825-1827

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

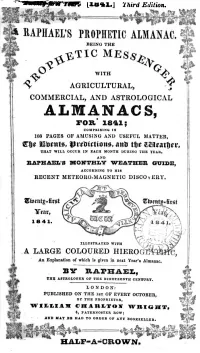

Raphael's Prophetic Almanac

Twenty - first Year . 1841 . ] Third Edition . & RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC SENGE . ELA BEING THE PROPHET ETIC MESSE WITH AGRICULTURAL , COMMERCIAL , AND ASTROLOGICAL ALMANACS , FOR ' 1841 ; COMPRISING IN 108 PAGES OF AMUSING AND USEFUL MATTER , The Events , Predictions , and the deather , THAT WILL OCCUR IN EACH MONTH DURING THE YEAR , AND RAPHAEL ' S MONTHLY WEATHER GUIDE , ACCORDING TO HIS RECENT METEORO - MAGNETIC DISCO v ERY . Twenty - first Twenty - first ¥ear , xids VCUAL 18 41 . V za ATIN W 184 1 . ILLUSTRATED WITH A LARGE COLOURED HIEROGLYPHIC , An Explanation of which is given in next Year ' s Almanac . BY RAPHAEL , ASTROLOGER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY . LONDON : PUBLISHED ON THE Ist OF EVERY OCTOBER , BY THE PROPRIETOR , WILLIAM CHARLTON WRIGHT . 4 , PATERNOSTER ROW ; AND MAY BE HAD TO ORDER OF ANY BOOKSELLER . HALF - A - OROWN . HUEROGLYPHIC FO TWENTY - FIRST ANNUAL NOTICE , 1841 . RAPHAEL continues to receive from all parts eulogistic ap proval of his labours . The sale last year mach increased , and RAPHAEL ' s industry has been prompted to make it still more useful and interesting . The uninitiated in the art of book - printing would be astonished were they to know the expense of getting out a work , small in appearance , but containing so many figures and calculations ; in truth , it is only the extensive circulation which RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC maintains which remune rates author and publisher . The work ( established twenty - one years ) requires much care and attention to understand it properly ; but , when this difficulty is conquered , our readers become ena . moured with the subject , fascinated with its contents , and recom . -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Revista De Historia De América Número 15

THE CHILEAN FAILURE TO OBTAIN BRITISH RECOGNITION. 1823-1828 The year 1823 witnessed a significant modification of the attitude of the British Foreign Office toward Chile. Soon after coming into office in 1822 Canning took up the ques• tion of Hispanic America. He apparently believed it possible to gain Cabinet support for immediate recognition of the Hispanic American states. Confidently he offered media• tion to Spain, but without result. Many influences were at work to bring about closer Anglo-Chilean relations at this time. ln June, 1818, Com- modore Bowles of the Royal Navy wrote that the quantity of British trade with Chile made very desirable the appoint• ment of a commercial agent in that country,1 and sugges• tions of this type grew more frequent as time passed. In April, 1822, meetings were held by London merchants for the purpose of "maintaining" commercial intercourse with the Hispanic American nations,2 and Liverpool shipowners and merchants petitioned for recognition of the indepen• dence of those countries. Canning, supported by such evidence of public support, was able in 1823 to carry through the Cabinet his project 1 Bowles to Admiralty, 7 June, 1818 (Public Record Office, Ad• miralty 1/23, N° 84, secret); JosÉ PACÍFICO OTERO, Historia del liber• tador (4 vols.; Buenos Aires, 1932), II, pp. 432-433. 2 FREDERIC L. PAXSON, The independence of the South American republics, a stu y in recognition and foreign policy (Philadelphia, 1903), p. 203. 285 Derechos Reservados Citar fuente Instituto Panamericano de Geografia e Historia Charles W. Centner. R. H. A., Núm. 15 for the appointment of commercial agents to the South American republics. -

Drawing After the Antique at the British Museum

Drawing after the Antique at the British Museum Supplementary Materials: Biographies of Students Admitted to Draw in the Townley Gallery, British Museum, with Facsimiles of the Gallery Register Pages (1809 – 1817) Essay by Martin Myrone Contents Facsimile, Transcription and Biographies • Page 1 • Page 2 • Page 3 • Page 4 • Page 5 • Page 6 • Page 7 Sources and Abbreviations • Manuscript Sources • Abbreviations for Online Resources • Further Online Resources • Abbreviations for Printed Sources • Further Printed Sources 1 of 120 Jan. 14 Mr Ralph Irvine, no.8 Gt. Howland St. [recommended by] Mr Planta/ 6 months This is probably intended for the Scottish landscape painter Hugh Irvine (1782– 1829), who exhibited from 8 Howland Street in 1809. “This young gentleman, at an early period of life, manifested a strong inclination for the study of art, and for several years his application has been unremitting. For some time he was a pupil of Mr Reinagle of London, whose merit as an artist is well known; and he has long been a close student in landscape afer Nature” (Thom, History of Aberdeen, 1: 198). He was the third son of Alexander Irvine, 18th laird of Drum, Aberdeenshire (1754–1844), and his wife Jean (Forbes; d.1786). His uncle was the artist and art dealer James Irvine (1757–1831). Alexander Irvine had four sons and a daughter; Alexander (b.1777), Charles (b.1780), Hugh, Francis, and daughter Christian. There is no record of a Ralph Irvine among the Irvines of Drum (Wimberley, Short Account), nor was there a Royal Academy student or exhibiting or listed artist of this name, so this was surely a clerical error or misunderstanding. -

The London Gazette, Issue 18356

. 18356. [ 937 ] The London Gazette. Bufclfefi^ -^. d fo\_g^ 8utl)oritg-^ c^ . FRIDAY, APRIL 27, 1827- Whitehall, April 24, 1827. The King has also been pleased to direct letters"' patent to be passed under the Great Seal, granting HE King has been pleased to direct letters patent to be passed under the Great Seal of the the dignity of a Baron of the United .Kingdom of T Great Britain and Ireland unto the Right Honour-"' United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, able William Conyngham Plunket, and the heirs constituting and appointing the Right Honourable George Canning) Francis Nathaniel Conyngham, male of his body lawfully begotten, by the name, Esq. (comnionly called Earl of Mount Charles); ttilc, and. title of Baron Plujiket, of Newtoxvn, in, Francis Leveson Gower, Esq. (commonly called Lord the county of Cork. Francis Leveson Gower) j and Edward .Granville Eliot, Esq. (commonly called Lord Eliot); snd also Whitehall, April 24, 1827. Edmund Alexander M'Naghten, Esq. to be Cbromis- The King has been pleased to constitute and sioners for executing'the offices of Treasurer of the appoint the Right Honourable James-- Ochoncar • Exchequer of Great Britain and Lord High Treasurer Lord Forbes to be His Majesty's High Commis- of Ireland. sioner to the General Assembly of the Church of. The King has also been pleased to direct letters Scotland, • patent to be passed under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom- of Great Britain and Ireland., India-Board, April 25, 1827. granting to the Right Honourable George Canning, The King has been pleased to direct letters. -

The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1820-1860

»OOM U üNviRsmr OFu om oti SEiATE HOUSE M,MET STRffif LOWDON WO* MU./ The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1 8 2 0 -1 8 6 0 Lucia Patrizio Gunning University College London, PhD Thesis, July 1997 Charles Thomas Newton and Dominic Ellis Colnaghi on horseback in Mitilene ProQuest Number: 10106684 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10106684 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 AOAOHÆC RCXAÎ k ÜNiVERSmf OF VDmCM gH^TE HOU^ / M A IH STTEEÎ t£riDOH WQÜ 3H I/ The British Consular Service in the Aegean 1820-1860 Lucia Patrizio Gunning University College London, PhD Thesis, July 1997 A bstract This thesis investigates the consular service in the Aegean from the final years of the Levant Company administration until 1860, a date that roughly coincides with the end of the British protectorate of the Ionian islands. The protectorate had made it necessary for the British Government to appoint consuls in the Aegean in order that they might look after the lonians. -

British Consuls in the Antebellum South, 1830

“DOUBLY FOREIGN”: BRITISH CONSULS IN THE ANTEBELLUM SOUTH, 1830 - 1860 By MICHELE ANDERS KINNEY Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2010 Copyright © by Michele Anders Kinney 2010 All Rights Reserved DEDICATED TO ANDERS You are my heart ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several people have contributed to the preparation of this dissertation. I wish to thank Dr. Stanley H. Palmer, who chaired the dissertation committee, provided invaluable encouragement throughout the project, and actively supported my endeavor. He is a wonderful mentor and I will be forever grateful and indebted to him. I also wish to thank the other members of the dissertation advisory committee, Dr. Douglas Richmond and Dr. Elisabeth Cawthon. Their critical evaluations were especially helpful in the structural modifications to my arguments that made the final product far superior than anything I would imagine. I am forever indebted to them. A special thanks goes to the University of Texas at Arlington’s Library staff. In particular, I would like to thank the staff of the Inter-Library Loan program. I also would like to thank the staffs that work at the many libraries I visited for their invaluable help in finding materials: the staff at the British National Archives, Kew, England; Duke University Special Collections; Emory University Special Collections; Georgia Historical Society Special Collections; the U.S. Regional Archives in Georgia; the University of South Carolina Special Collections; and Wallace State Genealogy Collection. -

George Canning and the Concert of Europe

George Canning and the Concert of Europe, September 1822-July 1824 By Norihito Yamada London School of Economics and Political Science Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD, University of London 2004 /m :\ ( l O N D A . ) UMI Number: U615511 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615511 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 1VA£S,£ S F 3 5 ^ Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This thesis is a study of the diplomacy of George Canning between September 1822 and July 1824. It offers a detailed analysis of Canning’s diplomacy on all the major international questions of the period in which his country’s vital interests were involved. Those questions were: (1) the Franco-Spanish crisis in 1822-3 and the French intervention in Spain in 1823; (2) the affairs of Spanish America including the question of the independence of Spain’s former colonies and that of the future of Cuba; (3) political instability in European Portugal; (4) the question of Brazilian independence; (5) the Greek War of Independence and the Russo-Turkish crisis. -

A Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Grace & Favour a Handbook of Who Lived Where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950

Grace & Favour A handbook of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Grace & Favour A handbook of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace 1750 to 1950 Sarah E Parker Grace & Favour 1 Published by Historic Royal Palaces Hampton Court Palace Surrey KT8 9AU © Historic Royal Palaces, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 1 873993 50 1 Edited by Clare Murphy Copyedited by Anne Marriott Printed by City Digital Limited Front cover image © The National Library, Vienna Historic Royal Palaces is a registered charity (no. 1068852). www.hrp.org.uk 2 Grace & Favour Contents Acknowledgements 4 Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Location of apartments 9 Introduction 14 A list of who lived where in Hampton Court Palace, 1750–1950 16 Appendix I: Possible residents whose apartments are unidentified 159 Appendix II: Senior office-holders employed at Hampton Court 163 Further reading 168 Index 170 Grace & Favour 3 Acknowledgements During the course of my research the trail was varied but never dull. I travelled across the country meeting many different people, none of whom had ever met me before, yet who invariably fetched me from the local station, drove me many miles, welcomed me into their homes and were extremely hospitable. I have encountered many people who generously gave up their valuable time and allowed, indeed, encouraged me to ask endless grace-and-favour-related questions. -

CITA I'ter Lii Tbere Seen» Te Have Been No Connection Bc,Tween Ihe

CITA I'TER lii TIRITISII j:ELATIONS WJ1'I 1 113TII AMERICA Tbere seen» te have been no connection bc,tween ihe intcrests thaI inspired Pitt te keep iii tonch with Francisco de Miranda in Ilie ]ast years of the eigh- teenth eentury and dic early enes of elle ninetoentli, titat impelled Sir 1-lome Ttiggs Popham to att.ack the Viecrovalty of Buenos Ayres en the bread groiinds oí comnaercial advantage and injury lo Spain, nud diese later interests thai devekped a rnercanti!e ojipusdion in Eugland fo emharrass tbe iniiiistry as 1-lenry C]ay' pólitieni opposition ernbarrasscd dic Amerien ti adininistration of John Quincy Adams aud bis presiclent, •James Monree. Tu Englaud there is a distinet break hetween these periods. Frotn un at ti- twle of hostilitv tn Spain ¡u t.he eariieryears. Gnt T3ritain passed through a star of friendly protection tliat drove thc Freneli cmi of ihe peninsula, luto an- (ither penad of semi-itostilir.y te dic restored Ferdi- nand. Duning this !ast penad, beginning roughly in 1815, the intercsts of Great Brhain were divided. Ori the nne liand uit enormous trade with Latín :nierica ;vas threatened with destruction. should Spain's colonial pobov come back with Spain's king. Eng/and ant! *south ;tmericcz 181 On tite ot.Iier, were Llie political intcrests oí Englaud in Europe, tite body of treacie.s cone]udcd during dic wars agaiit.st Napolcon, ilie iiewly-develoucd poliey of jaint action by tlic Powers. WithtbeLfflted Statesrecortiiiori vas a questiouofAinericau PQIiÍY; vitIi.Enlaud it was:nerelv ono of the Jications of lEuropeari polidc. -

ROBERT WILMOT HORTON and LIBERAL TORYISM by Stephen

ROBERT WILMOT HORTON AND LIBERAL TORYISM by Stephen Peter Lamont MA, MBA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Abstract This thesis examines aspects of the political career of Robert Wilmot Horton (1784-1841), a junior minister in the Tory governments of the 1820s and an advocate of state-aided emigration to the British colonies. It considers how far Wilmot conforms to existing conceptualisations of ‘liberal Toryism’, which are summarized in Chapter 1. Chapter 2 finds both ambition and principle in Wilmot’s choice of party, while identifying fundamental aspects of his political make-up, in particular his devotion to political economy and his hostility to political radicalism. Chapters 3 to 5 explore his economic thinking. Chapter 3 charts Wilmot’s gradual move away from a Malthusian approach to the problem of pauperism, and the resulting changes in his view of the role of emigration as a means of relief. Chapter 4 shows how his specific plan of colonization addressed broader considerations of imperial strategy and economic development. Chapter 5, exploring the wider context of economic debate, reveals Wilmot as an advocate of governmental activism in social policy, a critic of ‘economical reform’, and a moderate protectionist in the short term. Chapter 6 suggests that Wilmot, and the ministry as a whole, were driven by pragmatic rather than ideological considerations in their approach to the amelioration of slavery. Chapter 7 concludes that Wilmot’s advocacy of Catholic Emancipation, on grounds of expediency, conformed to the approach normally ascribed to liberal Tories in principle if not in detail. -

The Great Ambassador

THE GREAT AMBASSADOR A Study of the Diplomatic Career of the Right Hon ourable Stratford Canning, K.G., G.C.B., Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe, and the Epoch during Which He Served as the British Ambassador to the Sub1' Porte of the Ottoman Sultan era^ $6.25 W THE GREAT AMBASSADOR By Leo Gerald Byrne For a substantial part of the first half of the nineteenth century, the Right Honourable Stratford Canning served as Her Brittanic Majesty's Ambassador to the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Sultan. In this role, he played a significant part in a drama of high-level diplomacy and exercised a singular influence on the history of Europe and the Near East. He had, according to Sir Winston Churchill, "a wider knowledge of Turkey than any other Englishman of his day," and he was hailed by Tennyson as "the voice of England in the East." To the Turks, he was Buyuk Elchi— "the Great Ambassador." From this full-scale study of Sir Stratford's diplomatic career emerges a portrait of a skilled diplomat who was closely involved in a chain of ideas and events that have had a permanent bearing on human history. Leo Gerald Byrne is associated with Harper and Row, Publishers. THE GREAT AMBASSADOR THE GREAT AMBASSADOR A Study of the Diplomatic Career of the Right Honourable Stratford Canning, K.G., G.C.B., Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe, and the Epoch during Which He Served as the British Ambassador to the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Sultan By Leo Gerald Byrne Ohio State University Press Copyright © 1964 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 64-22404 PREFACE SOME years ago I chanced upon the record of Stratford Canning.