ROBERT WILMOT HORTON and LIBERAL TORYISM by Stephen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

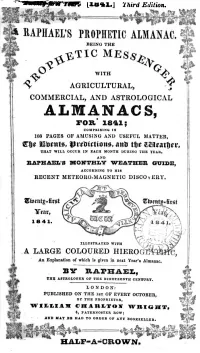

Raphael's Prophetic Almanac

Twenty - first Year . 1841 . ] Third Edition . & RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC SENGE . ELA BEING THE PROPHET ETIC MESSE WITH AGRICULTURAL , COMMERCIAL , AND ASTROLOGICAL ALMANACS , FOR ' 1841 ; COMPRISING IN 108 PAGES OF AMUSING AND USEFUL MATTER , The Events , Predictions , and the deather , THAT WILL OCCUR IN EACH MONTH DURING THE YEAR , AND RAPHAEL ' S MONTHLY WEATHER GUIDE , ACCORDING TO HIS RECENT METEORO - MAGNETIC DISCO v ERY . Twenty - first Twenty - first ¥ear , xids VCUAL 18 41 . V za ATIN W 184 1 . ILLUSTRATED WITH A LARGE COLOURED HIEROGLYPHIC , An Explanation of which is given in next Year ' s Almanac . BY RAPHAEL , ASTROLOGER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY . LONDON : PUBLISHED ON THE Ist OF EVERY OCTOBER , BY THE PROPRIETOR , WILLIAM CHARLTON WRIGHT . 4 , PATERNOSTER ROW ; AND MAY BE HAD TO ORDER OF ANY BOOKSELLER . HALF - A - OROWN . HUEROGLYPHIC FO TWENTY - FIRST ANNUAL NOTICE , 1841 . RAPHAEL continues to receive from all parts eulogistic ap proval of his labours . The sale last year mach increased , and RAPHAEL ' s industry has been prompted to make it still more useful and interesting . The uninitiated in the art of book - printing would be astonished were they to know the expense of getting out a work , small in appearance , but containing so many figures and calculations ; in truth , it is only the extensive circulation which RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC maintains which remune rates author and publisher . The work ( established twenty - one years ) requires much care and attention to understand it properly ; but , when this difficulty is conquered , our readers become ena . moured with the subject , fascinated with its contents , and recom . -

Review of the Year April 2000 – March 2001 508964AR.CHI 8/23/02 12:18 PM Page *2

508964AR.CHI 8/23/02 12:18 PM Page *1 THE ROTHSCHILD ARCHIVE Review of the year April 2000 – March 2001 508964AR.CHI 8/23/02 12:18 PM Page *2 Cover Picture: Mr S. V. J. Scott, a Clerk at N M Rothschild & Sons, photographed at his desk in the General Office, 1937 508964AR.CHI 8/23/02 12:18 PM Page *3 The Rothschild Archive Trust Trustees Emma Rothschild (Chair) Baron Eric de Rothschild Lionel de Rothschild Professor David Landes Anthony Chapman Staff Victor Gray (Director) Melanie Aspey (Archivist) Elaine Penn (Assistant Archivist) Richard Schofield (Assistant Archivist) Mandy Bell (Archives Assistant to October 2000) Gill Crust (Secretary) The Rothschild Archive, New Court, St. Swithin’s Lane, London EC4P 4DU Tel. +44 (0)20 7280 5874, Fax +44 (0)20 7280 5657, E-mail [email protected] Website: www.rothschildarchive.org Company No. 3702208 Registered Charity No. 1075340 508964AR.CHI 8/23/02 12:18 PM Page *4 508964AR.CHI 8/23/02 12:18 PM Page *5 CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................... 1 Emma Rothschild, Chairman of the Rothschild Archive Trust Review of the Year’s Work .................................................. 2 Victor Gray The Cash Nexus: Bankers and Politics in History ......................... 9 Professor Niall Ferguson ‘Up to our noses in smoke’ .................................................. 16 Richard Schofield Rothschild in the News....................................................... 22 Melanie Aspey Charles Stuart and the Secret Service ................................... -

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

A Companion to Nineteenth- Century Britain

A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Britain A COMPANION TO NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITAIN Edited by Chris Williams © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108, Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, Melbourne, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Chris Williams to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A companion to nineteenth-century Britain / edited by Chris Williams. p. cm. – (Blackwell companions to British history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-22579-X (alk. paper) 1. Great Britain – History – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Great Britain – Civilization – 19th century – Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Williams, Chris, 1963– II. Title. III. Series. DA530.C76 2004 941.081 – dc22 2003021511 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10 on 12 pt Galliard by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by TJ International For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO BRITISH HISTORY Published in association with The Historical Association This series provides sophisticated and authoritative overviews of the scholarship that has shaped our current understanding of British history. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

George Canning and the Representation of Liverpool, 1812-1823 1

'The Pride of my Publick Life': George Canning and the Representation of Liverpool, 1812-1823 1 Stephen M. Lee I George Canning (1770-1827) was one of the most significant figures on the Pittite side of British politics in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, and his successful campaign for a seat at Liverpool in 1812 both illustrated and contributed to the profound changes that his political career underwent during this period. Sandwiched between his failure to return to office in May-July 1812 following the assassination of Spencer Perceval and his decision to disband his personal following (his 'little Senate') in July i8i3,2 this campaign marked for Canning a turn away from the aristocratic political arena of Westminster, which he had come to find so frustrating, towards a political culture which, if at first alien, was replete with new possibilities. Moreover, Canning's experience as representative for Liverpool was indicative of wider changes in the political landscape of early nineteenth-century Britain. Before considering in detail some of the key aspects of Canning's outward turn, however, it will be useful to offer a brief description of the constituency of Liverpool and a short account of the elections that Canning fought there.3 1 This article is a revised version of chapter 3 of Stephen M. Lee, 'George Canning and the Tories, 1801-1827' (unpuh. Ph.D. thesis, Manchester Univ., 1999), PP- 93-128. 2 For a consideration of these two important episodes see Lee, 'Canning and the Tories', pp. 81-91. 1 Unless otherwise stated the following summary of the politics of Liverpool is 74 Stephen M. -

The Public and Private Life of Lord Chancellor Eldon

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ThepublicandprivatelifeofLordChancellorEldon HoraceTwiss > JHEMPMEyER ,"Bequest of oAlice Meyer 'Buck, 1882-1979 Stanford University libraries > I I I Mk ••• ."jJ-Jf* y,j\X:L ij.T .".[.DDF ""> ». ; v -,- ut y ftlftP * ii Willi i)\l I; ^ • **.*> H«>>« FR'iM •• ••.!;.!' »f. - i-: r w i v ^ &P v ii:-:) l:. Ill I the PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LIFE or LORD CHANCELLOR ELDON, WITH SELECTIONS FROM HIS CORRESPONDENCE. HORACE TWISS, ESQ. one op hkr Majesty's counsel. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. III. Ingens ara fuit, juxtaquc veterrima laurus Incumbcns ane, atque umbra complexa Penates." ViRG. JEn. lib. ii. 513, 514. Hard by, an aged laurel stood, and stretch'd Its arms o'er the great altar, in its shade Sheltering the household gods." LONDON: JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1844. w3 London : Printed by A. Spottiswoode, New- Street- Square. CONTENTS THE THIRD VOLUME CHAPTER L. 1827. Letter from Lord Eldon to Lady F. J. Bankes. — Mr. Brougham's Silk Gown. — Game Laws. — Unitarian Marriages. — Death and Character of Mr. Canning. — Formation of Lord Goderich's Ministry. — Duke of Wellington's Acceptance of the Command of the Army : Letters of the Duke, of Lord Goderich, of the King, and of Lord Eldon. — Letters of Lord Eldon to Lord Stowell and to Lady Eliza beth Repton. — Close of the Anecdote- Book : remaining Anec dotes ------- Page 1 CHAPTER LI. 1828. Dissolution of Lord Goderich's Ministry, and Formation of the Duke of Wellington's : Letters of Lord Eldon to Lady F. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

W-Orthies of England (Vol I, P

, ~ ·........ ; - --~":.!.::- SIR HECTOR LIVL,GSTOX Dt:'FF, K.B.E., C.::\I.G. THE SEWELLS IN THE NEW WORLD. BY SIR HECTOR L. DUFF, K.B.E., C.M.G. EXETER: WM. POLLARD & Co. LTD., BAMPFYLDE STREET. CONTENTS. PACE: PREFACE .. 0HAPTER !.-WILLIAM SEWELL THE FOUNDER AND HIS SON, HENRY SEWELL THE FIRST, circa 1500- 1628 .. .. .. :r CHAPTER 11.-HENRY SEWELL THE SECOND AND THIRD, AND THEIR :MIGRAnoNTOTHE NEW WoRLD, 1576-1700 - .. .. 13 0HAPTER 111.-MAJOR STEPHEN SEWELL; ms BROTHER· SAMUEL, CHIEF JUSTICE OF MAssACHUSETTS, AND THE TRAGEDY OF SALEM, 1652-1725 .. 25 CHAPTER IV.-JoNATHAN SEWELL THE FIRST AND SECOND, AND THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPEN· DENCE, I692-I796 .. • 4:r CHAPTER V.-JONATHAN SEWELL THE THIRD: THE GREAT CHIEF JUSTICE, 1766-t839 - - - 56 CHAPTER VI.-WILLIAM SEWELL, THE SHERIFF, AND HIS DESCENDANTS - .. 82 CHAPTER VIL-THE HERALDRY OF SEWELL .. .. 97 CHAPTER VIII.-THE HOUSE OF LIVINGSTON - 106 LIST OF ILLUSTR.,\TIONS. PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR - frontispiece CHIEF JUSTICE THE HON. JONATHAN SEWELL, LL.D. - - to face page Bo ALICE SEW~LL, LADY RUSSELL ,, ,, 94 ARMS BORNE BY THE SEWELLS OF NEW ENGLAND (text) - page 98 SEWELL QUARTERING AS GRANTED BY THE HERALDS) COLLEGE (text) 102 " ARMS OF DUFF OF CLYDEBANK, WITH BADGE SHOWING THE ARMORIAL DEVICES OF SEWELL AND LIVINGSTON ,, 104 PREFACE. This memoir does not profess to be, in any sense, a comprehensive history of the family to which it relates. It aims simply at recording my mother's lineal ancestry as far back as it can be traced with absolute certainty that is from the 4ays of Henry VII to our time-and at giving some account, though only in the barest outline, of those among her direct forbears whose lives have been specially distinguished or eventful. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Revista De Historia De América Número 15

THE CHILEAN FAILURE TO OBTAIN BRITISH RECOGNITION. 1823-1828 The year 1823 witnessed a significant modification of the attitude of the British Foreign Office toward Chile. Soon after coming into office in 1822 Canning took up the ques• tion of Hispanic America. He apparently believed it possible to gain Cabinet support for immediate recognition of the Hispanic American states. Confidently he offered media• tion to Spain, but without result. Many influences were at work to bring about closer Anglo-Chilean relations at this time. ln June, 1818, Com- modore Bowles of the Royal Navy wrote that the quantity of British trade with Chile made very desirable the appoint• ment of a commercial agent in that country,1 and sugges• tions of this type grew more frequent as time passed. In April, 1822, meetings were held by London merchants for the purpose of "maintaining" commercial intercourse with the Hispanic American nations,2 and Liverpool shipowners and merchants petitioned for recognition of the indepen• dence of those countries. Canning, supported by such evidence of public support, was able in 1823 to carry through the Cabinet his project 1 Bowles to Admiralty, 7 June, 1818 (Public Record Office, Ad• miralty 1/23, N° 84, secret); JosÉ PACÍFICO OTERO, Historia del liber• tador (4 vols.; Buenos Aires, 1932), II, pp. 432-433. 2 FREDERIC L. PAXSON, The independence of the South American republics, a stu y in recognition and foreign policy (Philadelphia, 1903), p. 203. 285 Derechos Reservados Citar fuente Instituto Panamericano de Geografia e Historia Charles W. Centner. R. H. A., Núm. 15 for the appointment of commercial agents to the South American republics. -

Economists' Papers 1750-2000

ECONOMISTS’PAPERS 1750 - 2000 A Guide to Archive and other Manuscript Sources for the History of British and Irish Economic Thought. ELECTRONIC EDITION ….the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the“ world is ruled by little else. “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.’ John Maynard Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) ECONOMISTS’ PAPERS 1750-2000 THE COMMITTEE OF THE GUIDE TO ARCHIVE SOURCES IN THE HISTORY OF ECONOMIC THOUGHT IN 1975 R.D. COLLISON BLACK Professor of Economics The Queen’s University of Belfast A.W. COATS Professor of Economic and Social History University of Nottingham B.A. CORRY Professor of Economics Queen Mary College, London (now deceased) R.H. ELLIS formerly Secretary of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts LORD ROBBINS formerly Professor of Economics University of London (now deceased) D.N. WINCH Professor of Economics University of Sussex ECONOMISTS' PAPERS 1750-2000 A Guide to Archive and other Manuscript Sources for the History of British and Irish Economic Thought Originally compiled by R. P. STURGES for the Committee of the Guide to Archive Sources in the History of Economic Thought, and now revised and expanded by SUSAN K. HOWSON, DONALD E. MOGGRIDGE, AND DONALD WINCH with the assistance of AZHAR HUSSAIN and the support of the ROYAL ECONOMIC SOCIETY © Royal Economic Society 1975 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission.