British Consuls in the Antebellum South, 1830

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

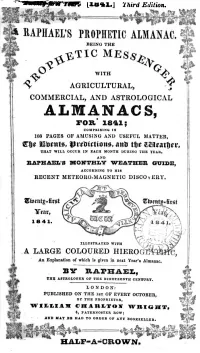

Raphael's Prophetic Almanac

Twenty - first Year . 1841 . ] Third Edition . & RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC SENGE . ELA BEING THE PROPHET ETIC MESSE WITH AGRICULTURAL , COMMERCIAL , AND ASTROLOGICAL ALMANACS , FOR ' 1841 ; COMPRISING IN 108 PAGES OF AMUSING AND USEFUL MATTER , The Events , Predictions , and the deather , THAT WILL OCCUR IN EACH MONTH DURING THE YEAR , AND RAPHAEL ' S MONTHLY WEATHER GUIDE , ACCORDING TO HIS RECENT METEORO - MAGNETIC DISCO v ERY . Twenty - first Twenty - first ¥ear , xids VCUAL 18 41 . V za ATIN W 184 1 . ILLUSTRATED WITH A LARGE COLOURED HIEROGLYPHIC , An Explanation of which is given in next Year ' s Almanac . BY RAPHAEL , ASTROLOGER OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY . LONDON : PUBLISHED ON THE Ist OF EVERY OCTOBER , BY THE PROPRIETOR , WILLIAM CHARLTON WRIGHT . 4 , PATERNOSTER ROW ; AND MAY BE HAD TO ORDER OF ANY BOOKSELLER . HALF - A - OROWN . HUEROGLYPHIC FO TWENTY - FIRST ANNUAL NOTICE , 1841 . RAPHAEL continues to receive from all parts eulogistic ap proval of his labours . The sale last year mach increased , and RAPHAEL ' s industry has been prompted to make it still more useful and interesting . The uninitiated in the art of book - printing would be astonished were they to know the expense of getting out a work , small in appearance , but containing so many figures and calculations ; in truth , it is only the extensive circulation which RAPHAEL ' S PROPHETIC ALMANAC maintains which remune rates author and publisher . The work ( established twenty - one years ) requires much care and attention to understand it properly ; but , when this difficulty is conquered , our readers become ena . moured with the subject , fascinated with its contents , and recom . -

Professor RDS Jack MA, Phd, Dlitt, FRSE

Professor R.D.S. Jack MA, PhD, DLitt, F.R.S.E., F.E.A.: Publications “Scottish Sonneteer and Welsh Metaphysical” in Studies in Scottish Literature 3 (1966): 240–7. “James VI and Renaissance Poetic Theory” in English 16 (1967): 208–11. “Montgomerie and the Pirates” in Studies in Scottish Literature 5 (1967): 133–36. “Drummond of Hawthornden: The Major Scottish Sources” in Studies in Scottish Literature 6 (1968): 36–46. “Imitation in the Scottish Sonnet” in Comparative Literature 20 (1968): 313–28. “The Lyrics of Alexander Montgomerie” in Review of English Studies 20 (1969): 168–81. “The Poetry of Alexander Craig” in Forum for Modern Language Studies 5 (1969): 377–84. With Ian Campbell (eds). Jamie the Saxt: A Historical Comedy; by Robert McLellan. London: Calder and Boyars, 1970. “William Fowler and Italian Literature” in Modern Language Review 65 (1970): 481– 92. “Sir William Mure and the Covenant” in Records of Scottish Church History Society 17 (1970): 1–14. “Dunbar and Lydgate” in Studies in Scottish Literature 8 (1971): 215–27. The Italian Influence on Scottish Literature. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1972. Scottish Prose 1550–1700. London: Calder and Boyars, 1972. “Scott and Italy” in Bell, Alan (ed.) Scott, Bicentenary Essays. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1973. 283–99. “The French Influence on Scottish Literature at the Court of King James VI” in Scottish Studies 2 (1974): 44–55. “Arthur’s Pilgrimage: A Study of Golagros and Gawane” in Studies in Scottish Literature 12 (1974): 1–20. “The Thre Prestis of Peblis and the Growth of Humanism in Scotland” in Review of English Studies 26 (1975): 257–70. -

Ÿþc O M M E N T S B Y G

Document:- A/CN.4/136 and Corr.1 (French only) and Add.1-11 Comments by Governments on the draft articles concerning consular intercourse and immunities provisionally adopted by the International Law Commission at its twelfth session, in 1960 Topic: Consular intercourse and immunities Extract from the Yearbook of the International Law Commission:- 1961 , vol. II Downloaded from the web site of the International Law Commission (http://www.un.org/law/ilc/index.htm) Copyright © United Nations Report of the Commission to the General Assembly 129 to the members of the Commission. A general discussion 45. The Inter-American Juridical Committee was of the matter was accordingly held at the 614th, 615th represented at the session by Mr. J. J. Caicedo Castilla, and 616th meetings. Attention is invited to the summary who, on behalf of the Committee, addressed the Com- records of the Commission containing the full discussion mission at the 597th meeting. on this question. 46. The Commission, at the 613th meeting, heard a statement by Professor Louis B. Sohn of the Harvard in. Co-operation with other bodies Law School on the draft convention on the international responsibility of States for injury to aliens, prepared 42. The Asian-African Legal Consultative Committee as part of the programme of international studies of the was represented at the session by Mr. H. Sabek, who, Law School. at the 6O5th meeting, made a statement on behalf of the Committee. IV. Date and place of the next session 43. The Commission's observer to the fourth session of the Committee, Mr. F. -

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA Prepared for City of Benicia Department of Public Works & Community Development Prepared by page & turnbull, inc. 1000 Sansome Street, Ste. 200, San Francisco CA 94111 415.362.5154 / www.page-turnbull.com Benicia Historic Context Statement FOREWORD “Benicia is a very pretty place; the situation is well chosen, the land gradually sloping back from the water, with ample space for the spread of the town. The anchorage is excellent, vessels of the largest size being able to tie so near shore as to land goods without lightering. The back country, including the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, is one of the finest agriculture districts in California. Notwithstanding these advantages, Benicia must always remain inferior in commercial advantages, both to San Francisco and Sacramento City.”1 So wrote Bayard Taylor in 1850, less than three years after Benicia’s founding, and another three years before the city would—at least briefly—serve as the capital of California. In the century that followed, Taylor’s assessment was echoed by many authors—that although Benicia had all the ingredients for a great metropolis, it was destined to remain in the shadow of others. Yet these assessments only tell a half truth. While Benicia never became the great commercial center envisioned by its founders, its role in Northern California history is nevertheless one that far outstrips the scale of its geography or the number of its citizens. Benicia gave rise to the first large industrial works in California, hosted the largest train ferries ever constructed, and housed the West Coast’s primary ordnance facility for over 100 years. -

Emancipation in St. Croix; Its Antecedents and Immediate Aftermath

N. Hall The victor vanquished: emancipation in St. Croix; its antecedents and immediate aftermath In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 58 (1984), no: 1/2, Leiden, 3-36 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl N. A. T. HALL THE VICTOR VANQUISHED EMANCIPATION IN ST. CROIXJ ITS ANTECEDENTS AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH INTRODUCTION The slave uprising of 2-3 July 1848 in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, belongs to that splendidly isolated category of Caribbean slave revolts which succeeded if, that is, one defines success in the narrow sense of the legal termination of servitude. The sequence of events can be briefly rehearsed. On the night of Sunday 2 July, signal fires were lit on the estates of western St. Croix, estate bells began to ring and conch shells blown, and by Monday morning, 3 July, some 8000 slaves had converged in front of Frederiksted fort demanding their freedom. In the early hours of Monday morning, the governor general Peter von Scholten, who had only hours before returned from a visit to neighbouring St. Thomas, sum- moned a meeting of his senior advisers in Christiansted (Bass End), the island's capital. Among them was Lt. Capt. Irminger, commander of the Danish West Indian naval station, who urged the use of force, including bombardment from the sea to disperse the insurgents, and the deployment of a detachment of soldiers and marines from his frigate (f)rnen. Von Scholten kept his own counsels. No troops were despatched along the arterial Centreline road and, although he gave Irminger permission to sail around the coast to beleaguered Frederiksted (West End), he went overland himself and arrived in town sometime around 4 p.m. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Finlay Scots Lawyers Stairsoc

This is a publication of The Stair Society. This publication is licensed by John Finlay and The Stair Society under Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC-ND and may be freely shared for non-commercial purposes so long as the creators are credited. John Finlay, ‘Scots Lawyers, England, and the Union of 1707’, in: Stair Society 62 [Miscellany VII] (2015) 243-263 http://doi.org/10.36098/stairsoc/9781872517292.4 The Stair Society was founded in 1934 to encourage the study and advance the knowledge of the history of Scots Law, by the publication of original works, and by the reprinting and editing of works of rarity or importance. As a member of the Society, you will receive a copy of every volume published during your membership. Volumes are bound in hardcover and produced to a high quality. We also offer the opportunity to purchase past volumes in stock at substantially discounted prices; pre-publication access to material in press; and free access to the complete electronic versions of Stair Soci- ety publications on HeinOnline. Membership of the society is open to all with an interest in the history of Scots law, whether based in the UK or abroad. Indivi- dual members include practising lawyers, legal academics, law students and others. Corporate members include a wide range of academic and professional institutions, libraries and law firms. Membership rates are modest, and we offer concessionary rates for students, recently qualified and called solicitors and advocates, and those undertaking training for these qualifica- tions. Please visit: http://stairsociety.org/membership/apply SCOTS LAWYERS, ENGLAND, AND THE UNION OF 1707 JOHN FINLAY I Support from the legal profession in Scotland was important in securing parliamentary union in 1707.1 At this time, the membership of the Faculty of Advocates in Edinburgh was greater than it had ever been, therefore their support, and that of the judges in the Court of Session, was worth gaining. -

Revista De Historia De América Número 15

THE CHILEAN FAILURE TO OBTAIN BRITISH RECOGNITION. 1823-1828 The year 1823 witnessed a significant modification of the attitude of the British Foreign Office toward Chile. Soon after coming into office in 1822 Canning took up the ques• tion of Hispanic America. He apparently believed it possible to gain Cabinet support for immediate recognition of the Hispanic American states. Confidently he offered media• tion to Spain, but without result. Many influences were at work to bring about closer Anglo-Chilean relations at this time. ln June, 1818, Com- modore Bowles of the Royal Navy wrote that the quantity of British trade with Chile made very desirable the appoint• ment of a commercial agent in that country,1 and sugges• tions of this type grew more frequent as time passed. In April, 1822, meetings were held by London merchants for the purpose of "maintaining" commercial intercourse with the Hispanic American nations,2 and Liverpool shipowners and merchants petitioned for recognition of the indepen• dence of those countries. Canning, supported by such evidence of public support, was able in 1823 to carry through the Cabinet his project 1 Bowles to Admiralty, 7 June, 1818 (Public Record Office, Ad• miralty 1/23, N° 84, secret); JosÉ PACÍFICO OTERO, Historia del liber• tador (4 vols.; Buenos Aires, 1932), II, pp. 432-433. 2 FREDERIC L. PAXSON, The independence of the South American republics, a stu y in recognition and foreign policy (Philadelphia, 1903), p. 203. 285 Derechos Reservados Citar fuente Instituto Panamericano de Geografia e Historia Charles W. Centner. R. H. A., Núm. 15 for the appointment of commercial agents to the South American republics. -

Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations

UNITED NATIONS United States of America Vienna Convention on Relations and Optional Protocol on Disputes Multilateral—Diplomatic Relations—Apr. 18,1961 UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON DIPLOMATIC INTERCOURSE AND IMMUNITIES VIENNA CONVENTION ON DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS UNITED NATIONS 1961 MULTILATERAL Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and Optional Protocol on Disputes Done at Vienna April 18, 1961; Ratification advised by the Senate of the United States of America September 14, 1965; Ratified by the President of the United States of America November 8, 1972 Ratification of the United States of America deposited with the Secretary-General of the United Nations November 13, 1972; Proclaimed by the President of the United States of America November 24, 1972; Entered into force with respect to the United States of America December 13, 1972. BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA A PROCLAMATION CONSIDERING THAT: The Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and the Optional Proto- col Concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes were opened for sig- nature on April 18, 1961 and were signed on behalf of the United States of America on June 29, 1961, certified copies of which are hereto annexed; The Senate of the United States of America by its resolution of Septem- ber 14, 1965, two-thirds of the Senators present concurring therein, gave its advise and consent to ratification of the Convention and the Optional Proto- col; On November 8, 1972 the President of the United States of America ratified the Convention and the Optional Protocol, in pursuance of the advice and consent of the Senate; The United States of America deposited its instrument of ratification of the Convention, and the Optional Protocol on November 13, 1972, in accor- dance with the provisions of Article 49 of the Convention and Article VI of the Optional Protocol; TIAS 7502 INTRODUCTION VIENNA CONVENTION ON DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS The States Parties to the present Convention, Recalling that people of all nations from ancient times have recognized the status of diplomatic agents. -

Guidelines for the Honorary Consuls of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Ministry

Guidelines for the Honorary Consuls of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Royal Government of Bhutan Thimphu August 2019 1 Section I Introduction In view of the growing need for consular services abroad and promotion of trade, commerce, and people to people contact, the Royal Government of Bhutan hereby adopts the revised guidelines 2019. Section II General Provisions 1. The Guideline is based on the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963. 2. The Honorary Consuls shall represent the interests of the Kingdom of Bhutan and its citizens in the receiving State. 3. The Honorary Consuls may enjoy facilities, privileges and immunities in accordance with the laws and regulations of the receiving State. 4. All expenses related to the establishment, activities of the Office of the Honorary Consul, the exercise of official attributions and representation of the interests of the Kingdom of Bhutan in the territory of the receiving State shall be borne by the Honorary Consuls. Section III Criteria for Candidature The proposed candidate for the post of an Honorary Consul must fulfil the following criteria: 1. He/She must be a citizen or permanent resident of that State. He/She must reside in the country/city of his/her proposed consular jurisdiction. 2. He/She must be of sound character, high standing and enjoy social prominence and influence with authorities and the business communities in the consular jurisdiction. 3. He/She must be able to operate from his/her own resources. 4. He/She must not simultaneously represent another country in any capacity or exercise the function of the honorary consul of another State. -

Table of Contents

PANAMA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward W. Clark 1946-1949 Consular Officer, Panama City 1960-1963 Deputy Chief of Mission, Panama City Walter J. Silva 1954-1955 Courier Service, Panama City Peter S. Bridges 1959-1961 Visa Officer, Panama City Clarence A. Boonstra 1959-1962 Political Advisor to Armed Forces, Panama Joseph S. Farland 1960-1963 Ambassador, Panama Arnold Denys 1961-1964 Communications Supervisor/Consular Officer, Panama City David E. Simcox 1962-1966 Political Officer/Principal Officer, Panama City Stephen Bosworth 1962-1963 Rotation Officer, Panama City 1963-1964 Principle Officer, Colon 1964 Consular Officer, Panama City Donald McConville 1963-1965 Rotation Officer, Panama City John N. Irwin II 1963-1967 US Representative, Panama Canal Treaty Negotiations Clyde Donald Taylor 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Panama City Stephen Bosworth 1964-1967 Panama Desk Officer, Washington, DC Harry Haven Kendall 1964-1967 Information Officer, USIS, Panama City Robert F. Woodward 1965-1967 Advisor, Panama Canal Treaty Negotiations Clarke McCurdy Brintnall 1966-1969 Watch Officer/Intelligence Analyst, US Southern Command, Panama David Lazar 1968-1970 USAID Director, Panama City 1 Ronald D. Godard 1968-1970 Rotational Officer, Panama City William T. Pryce 1968-1971 Political Officer, Panama City Brandon Grove 1969-1971 Director of Panamanian Affairs, Washington, DC Park D. Massey 1969-1971 Development Officer, USAID, Panama City Robert M. Sayre 1969-1972 Ambassador, Panama J. Phillip McLean 1970-1973 Political Officer, Panama City Herbert Thompson 1970-1973 Deputy Chief of Mission, Panama City Richard B. Finn 1971-1973 Panama Canal Negotiating Team James R. Meenan 1972-1974 USAID Auditor, Regional Audit Office, Panama City Patrick F. -

East Renfrewshire Survey of Gardens & Designed Landscapes

THE GARDEN HISTORY SOCIETY IN SCOTLAND EAST RENFREWSHIRE SURVEY OF GARDENS & DESIGNED LANDSCAPES RECORDING FORM A. GENERAL SITE INFORMATION (Expand boxes as necessary) SITE NAME: Caldwell House Estate ALTERNATIVE NAMES OR SPELLINGS: Coldwel (Pont), Callwall (Roy), Caldwall (various 18th century documents including those of Robert Adam) ADDRESS AND POSTCODE: Caldwell House, Gleniffer Road, Uplawmoor, Glasgow G78 4BE GRID REFERENCE: NS 41495415 LOCAL AUTHORITY: East Renfrewshire (Historical Counties Renfrewshire & Ayrshire) PARISH: Neilston. Has at times been in Beith Parish Ayrshire but is mostly associated with Neilston. The most recent change was as part of The Renfrew and Cunninghame Districts (Caldwell House Estate) Boundaries Amendment Order 1989. INCLUDED IN AN INVENTORY OF GARDENS & DESIGNED LANDSCAPES IN SCOTLAND: No 1 TYPE OF SITE: (eg. Landscaped estate, private garden, public park/gardens, corporate/institutional landscape, cemetery, allotments, or other – please specify) Landscaped Estate SITE OWNERSHIP & CONTACT: (Where site is in divided ownership please list all owners and indicate areas owned on map if possible) Complex recent ownership. Main house and grounds now understood to be under the ownership of JOK developments. Main contact for further information is Ms Julie Nicol, Planning Department, East Renfrewshire Council. Area around Ram’s Head Cottage and land to south as far as Caldwell House totalling approximately 10 acres under private ownership. Area around Roudans Cottage near Gleniffer Road entrance under private ownership. Area around former boiler room and glass house adjacent to Roudans Cottage under separate ownership. SIZE IN HECTARES OR ACRES: Caldwell House lies in the middle of Caldwell Estate. The estate extends to 67.4 hectares (166 acres) or thereby.