Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

Convocations Called by Edward IV and Richard of Gloucester in 1483: Did They Ever Take Place?

Convocations Called by Edward IV and Richard of Gloucester in 1483: Did They Ever Take Place? ANNETTE CARSON IN I 4 8 3 , THE YEAR OF THREE KINGS, a series of dramatic regime changes led to unforeseen disruptions in the normal machinery of English government. It was a year of many plans unfulfilled, beginning with those of Edward IV who was still concerned over unfinished hostilities with James III of Scotland, and had also made clear his intention to wreak revenge on the treacherous Louis XI of France. All this came to naught when Edward's life ended suddenly and unexpectedly on 9 April. His twelve-year-old son, Edward V, was scheduled to be crowned as his successor, with Edward IV's last living brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, appointed as lord protector. But within two months Richard had become king in his place, with young Edward deposed on the grounds that his father's marriage to Queen Elizabeth Woodville was both bigamous and secret, thus rendering their children illegitimate. Since this article will be looking closely at the events of this brief period, perhaps it will be useful to start with a very simplified chronology of early 1483. The ques- tions addressed concern two convocations, called by royal mandate in February and May respectively, about which some erroneous assumptions will be revealed.' January/February Edward IV's parliament. 3 February A convocation of the southern clergy is called by writ of Edward IV. 9 April Edward IV dies. 17-19 April Edward's funeral takes place, attended by leading clergy. -

The English Atlantic World: a View from London Alison Games Georgetown University

The English Atlantic World: A View from London Alison Games Georgetown University William Booth occupied an unfortunate status in the land of primogeniture and the entailed estate. A younger son from a Cheshire family, he went up to London in May, 1628, "to get any servis worth haveinge." His letters to his oldest brother John, who had inherited the bulk of their father's estate, and John's responses, drafted on the back of William's original missives, describe the circumstances which enticed men to London in search of work and the misfortunes that subsequently ushered them overseas. William Booth, unable to find suitable employment in the metropolis, implored his brother John to procure a letter of introduction on his behalf from their cousin Morton. Plaintively reminding his brother "how chargeable a place London is to live in," he also requested funds for a suit of clothes in order to make himself more presentable in his quest for palatable employment. William threatened his older brother with military service on the continent if he could find no position in London, preferring to "goe into the lowcuntries or eles wth some man of warre" than to stay in London. John Booth, dismayed by his sibling's martial inclination, offered William money from his own portion of their father's estate rather than permit William to squander his own smaller share. In what proved to be a gross misreading of William's character but perhaps a sound assessment of his desire for the status becoming his ambitions, John urged William to seek a position with a bishop. -

Parish Churches in the Diocese of Rochester, C. 1320-C. 1520

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society PARISH CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER, c. 1320 - c. 1520 COLIN FLIGHT The core of this article is an alphabetical list of the parish churches belonging to the diocese of Rochester in the fifteenth century. Their distribution is shown by the accompanying map (Fig. 1). More precisely, the list as it stands describes the situation existing c. 1420; but information is also provided which will enable the reader to modify the list so that it describes the situation existing at any other chosen date between c. 1320 and c. 1520. Though many of the facts reported here may seem sufficiently well-known, the author is not aware of any previously published list which can claim to be both comprehensive in scope and accurate in detail. The information given below is all taken from primary sources, or, failing that, from secondary sources closely dependent on the primary sources. Where there is some uncertainty, this is stated. Apart from these admittedly doubtful points, the list is believed to be perfectly reliable. Readers who notice any errors or who can shed any further light on the areas of uncertainty should kindly inform the author. Before anything else, it needs to be understood that a large part of the diocese of Rochester did not come under the bishop's jurisdict- ion. More than thirty parishes, roughly one quarter of the total number, were subject to the archbishop of Canterbury. They constit- uted what was called the deanery of Shoreham. -

Lisa L. Ford Phd Thesis

CONCILIAR POLITICS AND ADMINISTRATION IN THE REIGN OF HENRY VII Lisa L. Ford A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2001 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7121 This item is protected by original copyright Conciliar Politics and Administration in the Reign of Henry VII Lisa L. Ford A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of St. Andrews April 2001 DECLARATIONS (i) I, Lisa Lynn Ford, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 100,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. Signature of candidate' (ii) I was admitted as a reseach student in January 1996 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in January 1997; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between 1996 and 2001. / 1 Date: ') -:::S;{:}'(j. )fJ1;;/ Signature of candidate: 1/ - / i (iii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date \ (If (Ls-> 1 Signature of supervisor: (iv) In submitting this thesis to the University of St. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

INDULGENCES and SOLIDARITY in LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND By

INDULGENCES AND SOLIDARITY IN LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND by ANN F. BRODEUR A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Copyright by Ann F. Brodeur, 2015 Indulgences and Solidarity in Late Medieval England Ann F. Brodeur Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Medieval indulgences have long had a troubled public image, grounded in centuries of confessional discord. Were they simply a crass form of medieval religious commercialism and a spiritual fraud, as the reforming archbishop Cranmer charged in his 1543 appeal to raise funds for Henry VIII’s contributions against the Turks? Or were they perceived and used in a different manner? In his influential work, Indulgences in Late Medieval England: Passports to Paradise, R.N. Swanson offered fresh arguments for the centrality and popularity of indulgences in the devotional landscape of medieval England, and thoroughly documented the doctrinal development and administrative apparatus that grew up around indulgences. How they functioned within the English social and devotional landscape, particularly at the local level, is the focus of this thesis. Through an investigation of published episcopal registers, my thesis explores the social impact of indulgences at the diocesan level by examining the context, aims, and social make up of the beneficiaries, as well as the spiritual and social expectations of the granting bishops. It first explores personal indulgences given to benefit individuals, specifically the deserving poor and ransomed captives, before examining indulgences ii given to local institutions, particularly hospitals and parishes. Throughout this study, I show that both lay people and bishops used indulgences to build, reinforce or maintain solidarity and social bonds between diverse groups. -

MFB (PDF , 39Kb)

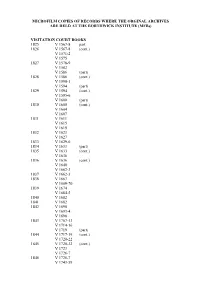

MICROFILM COPIES OF RECORDS WHERE THE ORGINAL ARCHIVES ARE HELD AT THE BORTHWICK INSTITUTE (MFBs) VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1825 V 1567-8 part 1826 V 1567-8 (cont.) V 1571-2 V 1575 1827 V 1578-9 V 1582 V 1586 (part) 1828 V 1586 (cont.) V 1590-1 V 1594 (part) 1829 V 1594 (cont.) V 1595-6 V 1600 (part) 1830 V 1600 (cont.) V 1604 V 1607 1831 V 1611 V 1615 V 1619 1832 V 1623 V 1627 1833 V 1629-0 1834 V 1633 (part) 1835 V 1633 (cont.) V 1636 1836 V 1636 (cont.) V 1640 V 1662-3 1837 V 1662-3 1838 V 1667 V 1669-70 1839 V 1674 V 1684-5 1840 V 1682 1841 V 1682 1842 V 1690 V 1693-4 V 1698 1843 V 1707 -13 V 1714-16 V 1719 (part) 1844 V 1717-19 (cont.) V 1720-22 1845 V 1720-22 (cont.) V 1723 V 1726-7 1846 V 1726-7 V 1743-59 1847 V 1743 (V Book and Papers) V 1748-9 (V Papers) 1848 V 1748-9 (V Book) V 1759-60 (V Book, Papers) 1849 V 1764 (C Book, Ex Book, Papers) V 1770 (part C Book) 1850 V 1770 (cont., CB) V 1777 (C. Book, Papers) V 1781 (Exh Book) 1851 V 1781 (CB and Papers) V 1786 (Papers) 1852 V 1786 (cont., CB) V 1791 (Papers) V 1809 (Call Book and Papers) V 1817 (Call Book) 1853 V 1817, cont. (Call Book) V 1825 (Call Book and Papers) V 1841 (Papers) 1854 V 1841 (Papers cont) V 1849 (Call Book and Papers) V 1853 (Call Book and Papers) CLEVELAND VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1855 C/V/CB. -

York Minster Conservation Management Plan 2021

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOL. 2 GAZETTEERS DRAFT APRIL 2021 Alan Baxter YORK MINSTER CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOL. 2 GAZETTEERS PREPARED FOR THE CHAPTER OF YORK DRAFT APRIL 2021 HOW TO USE THIS DOCUMENT This document is designed to be viewed digitally using a number of interactive features to aid navigation. These features include bookmarks (in the left-hand panel), hyperlinks (identified by blue text) to cross reference between sections, and interactive plans at the beginning of Vol III, the Gazetteers, which areAPRIL used to locate individual 2021 gazetteer entries. DRAFT It can be useful to load a ‘previous view’ button in the pdf reader software in order to retrace steps having followed a hyperlink. To load the previous view button in Adobe Acrobat X go to View/Show/ Hide/Toolbar Items/Page Navigation/Show All Page Navigation Tools. The ‘previous view’ button is a blue circle with a white arrow pointing left. York Minster CMP / April 2021 DRAFT Alan Baxter CONTENTS CONTENTS Introduction to the Gazetteers ................................................................................................ i Exterior .................................................................................................................................... 1 01: West Towers and West Front ................................................................................. 1 02: Nave north elevation ............................................................................................... 7 03: North Transept elevations.................................................................................... -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

Cathedral Deans of the Yorkist Age A. COMPTON REEVES When Richard III became king, be appointed a cathedral dean to be the keeper of his privy seal and in consequence one of the most important figures in the royal administrationThis was John Gunthorpe, Dean of Wells Cathedral, who had served Edward IV in a variety of capacities.1 Gunthorpe (more about whom shortly) was a highly accomplished man, and curiosity about him and his contemporary deans is an avenue of inquiry into the Yorkist age. To examine cathedral deans is to look at a fairly small group of ecclesiastics with considerable influence in their localities. As the chief officer in their cathedral communities they were administrators with weighty responsibilities. In those cases where they became deans through royal patronage or influence, it is of interest to learn what training and experience these men had to attract the attention of the Yorkist kings. It will also be useful to learn if the Yorkistkings routinely used the office of clean to reward adherents or if they looked to the kingdom’s cathedral deans as a pool of governmental talent. There is, of course, the fact that these men are of inherent interest simply because they were cathedral deans. A few words are necessary about cathedrals in the Yorkist age. England and Wales were organized ecclesiastically as the provinces of Canterbury and York, with an archbishop in charge of his own diocese as well as being supervisor of the other dioceses in his province. A cathedral held the tatbedra, or seat, of a bishop, and was the mother church of a diocese. -

The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86508-1 - The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M. Smith Frontmatter More information THE HEADS OF RELIGIOUS HOUSES ENGLAND AND WALES 1377–1540 This final volume of The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales takes the lists of monastic superiors from 1377 to the dissolution of the monastic houses ending in 1540 and so concludes a reference work covering 600 years of monastic history. In addition to surviving monastic archives, record sources have also been provided by episcopal and papal registers, governmental archives, court records, and private, family and estate collections. Full references are given for establishing the dates and outline of the career of each abbot or prior, abbess or prioress, when known. The lists are arranged by order: the Benedictine houses (independent; dependencies; and alien priories); the Cluniacs; the Grandmontines; the Cistercians; the Carthusians; the Augustinian canons; the Premonstratensians; the Gilbertine order; the Trinitarian houses; the Bonhommes; and the nuns. An intro- duction discusses the use and history of the lists and examines critically the sources on which they are based. david m. smith is Professor Emeritus, University of York. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86508-1 - The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M. Smith Frontmatter More information THE HEADS OF RELIGIOUS HOUSES ENGLAND AND WALES III 1377–1540 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH Professor Emeritus, University of York © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86508-1 - The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M.