Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

The English Atlantic World: a View from London Alison Games Georgetown University

The English Atlantic World: A View from London Alison Games Georgetown University William Booth occupied an unfortunate status in the land of primogeniture and the entailed estate. A younger son from a Cheshire family, he went up to London in May, 1628, "to get any servis worth haveinge." His letters to his oldest brother John, who had inherited the bulk of their father's estate, and John's responses, drafted on the back of William's original missives, describe the circumstances which enticed men to London in search of work and the misfortunes that subsequently ushered them overseas. William Booth, unable to find suitable employment in the metropolis, implored his brother John to procure a letter of introduction on his behalf from their cousin Morton. Plaintively reminding his brother "how chargeable a place London is to live in," he also requested funds for a suit of clothes in order to make himself more presentable in his quest for palatable employment. William threatened his older brother with military service on the continent if he could find no position in London, preferring to "goe into the lowcuntries or eles wth some man of warre" than to stay in London. John Booth, dismayed by his sibling's martial inclination, offered William money from his own portion of their father's estate rather than permit William to squander his own smaller share. In what proved to be a gross misreading of William's character but perhaps a sound assessment of his desire for the status becoming his ambitions, John urged William to seek a position with a bishop. -

The College and Canons of St Stephen's, Westminster, 1348

The College and Canons of St Stephen’s, Westminster, 1348 - 1548 Volume I of II Elizabeth Biggs PhD University of York History October 2016 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the college founded by Edward III in his principal palace of Westminster in 1348 and dissolved by Edward VI in 1548 in order to examine issues of royal patronage, the relationships of the Church to the Crown, and institutional networks across the later Middle Ages. As no internal archive survives from St Stephen’s College, this thesis depends on comparison with and reconstruction from royal records and the archives of other institutions, including those of its sister college, St George’s, Windsor. In so doing, it has two main aims: to place St Stephen’s College back into its place at the heart of Westminster’s political, religious and administrative life; and to develop a method for institutional history that is concerned more with connections than solely with the internal workings of a single institution. As there has been no full scholarly study of St Stephen’s College, this thesis provides a complete institutional history of the college from foundation to dissolution before turning to thematic consideration of its place in royal administration, music and worship, and the manor of Westminster. The circumstances and processes surrounding its foundation are compared with other such colleges to understand the multiple agencies that formed St Stephen’s, including that of the canons themselves. Kings and their relatives used St Stephen’s for their private worship and as a site of visible royal piety. -

Subject Categories

Subject Categories Click on a Subject Category below: Anthropology Archaeology Astronomy and Astrophysics Atmospheric Sciences and Oceanography Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Business and Finance Cellular and Developmental Biology and Genetics Chemistry Communications, Journalism, Editing, and Publishing Computer Sciences and Technology Economics Educational, Scientific, Cultural, and Philanthropic Administration (Nongovernmental) Engineering and Technology Geology and Mineralogy Geophysics, Geography, and Other Earth Sciences History Law and Jurisprudence Literary Scholarship and Criticism and Language Literature (Creative Writing) Mathematics and Statistics Medicine and Health Microbiology and Immunology Natural History and Ecology; Evolutionary and Population Biology Neurosciences, Cognitive Sciences, and Behavioral Biology Performing Arts and Music – Criticism and Practice Philosophy Physics Physiology and Pharmacology Plant Sciences Political Science / International Relations Psychology / Education Public Affairs, Administration, and Policy (Governmental and Intergovernmental) Sociology / Demography Theology and Ministerial Practice Visual Arts, Art History, and Architecture Zoology Subject Categories of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1780–2019 Das, Veena Gellner, Ernest Andre Leach, Edmund Ronald Anthropology Davis, Allison (William Gluckman, Max (Herman Leakey, Mary Douglas Allison) Max) Nicol Adams, Robert Descola, Philippe Goddard, Pliny Earle Leakey, Richard Erskine McCormick DeVore, Irven (Boyd Goodenough, Ward Hunt Frere Adler-Lomnitz, Larissa Irven) Goody, John Rankine Lee, Richard Borshay Appadurai, Arjun Dillehay, Tom D. Grayson, Donald K. LeVine, Robert Alan Bailey, Frederick George Dixon, Roland Burrage Greenberg, Joseph Levi-Strauss, Claude Barth, Fredrik Dodge, Ernest Stanley Harold Levy, Robert Isaac Bateson, Gregory Donnan, Christopher B. Greenhouse, Carol J. Levy, Thomas Evan Beall, Cynthia M. Douglas, Mary Margaret Grove, David C. Lewis, Oscar Benedict, Ruth Fulton Du Bois, Cora Alice Gumperz, John J. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

MFB (PDF , 39Kb)

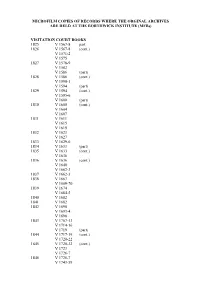

MICROFILM COPIES OF RECORDS WHERE THE ORGINAL ARCHIVES ARE HELD AT THE BORTHWICK INSTITUTE (MFBs) VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1825 V 1567-8 part 1826 V 1567-8 (cont.) V 1571-2 V 1575 1827 V 1578-9 V 1582 V 1586 (part) 1828 V 1586 (cont.) V 1590-1 V 1594 (part) 1829 V 1594 (cont.) V 1595-6 V 1600 (part) 1830 V 1600 (cont.) V 1604 V 1607 1831 V 1611 V 1615 V 1619 1832 V 1623 V 1627 1833 V 1629-0 1834 V 1633 (part) 1835 V 1633 (cont.) V 1636 1836 V 1636 (cont.) V 1640 V 1662-3 1837 V 1662-3 1838 V 1667 V 1669-70 1839 V 1674 V 1684-5 1840 V 1682 1841 V 1682 1842 V 1690 V 1693-4 V 1698 1843 V 1707 -13 V 1714-16 V 1719 (part) 1844 V 1717-19 (cont.) V 1720-22 1845 V 1720-22 (cont.) V 1723 V 1726-7 1846 V 1726-7 V 1743-59 1847 V 1743 (V Book and Papers) V 1748-9 (V Papers) 1848 V 1748-9 (V Book) V 1759-60 (V Book, Papers) 1849 V 1764 (C Book, Ex Book, Papers) V 1770 (part C Book) 1850 V 1770 (cont., CB) V 1777 (C. Book, Papers) V 1781 (Exh Book) 1851 V 1781 (CB and Papers) V 1786 (Papers) 1852 V 1786 (cont., CB) V 1791 (Papers) V 1809 (Call Book and Papers) V 1817 (Call Book) 1853 V 1817, cont. (Call Book) V 1825 (Call Book and Papers) V 1841 (Papers) 1854 V 1841 (Papers cont) V 1849 (Call Book and Papers) V 1853 (Call Book and Papers) CLEVELAND VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1855 C/V/CB. -

The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86508-1 - The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M. Smith Frontmatter More information THE HEADS OF RELIGIOUS HOUSES ENGLAND AND WALES 1377–1540 This final volume of The Heads of Religious Houses: England and Wales takes the lists of monastic superiors from 1377 to the dissolution of the monastic houses ending in 1540 and so concludes a reference work covering 600 years of monastic history. In addition to surviving monastic archives, record sources have also been provided by episcopal and papal registers, governmental archives, court records, and private, family and estate collections. Full references are given for establishing the dates and outline of the career of each abbot or prior, abbess or prioress, when known. The lists are arranged by order: the Benedictine houses (independent; dependencies; and alien priories); the Cluniacs; the Grandmontines; the Cistercians; the Carthusians; the Augustinian canons; the Premonstratensians; the Gilbertine order; the Trinitarian houses; the Bonhommes; and the nuns. An intro- duction discusses the use and history of the lists and examines critically the sources on which they are based. david m. smith is Professor Emeritus, University of York. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86508-1 - The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M. Smith Frontmatter More information THE HEADS OF RELIGIOUS HOUSES ENGLAND AND WALES III 1377–1540 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH Professor Emeritus, University of York © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86508-1 - The Heads of Religious Houses England and Wales III, 1377-1540 Edited by David M. -

Sussex. Chichester

DIRECTORY.] SUSSEX. CHICHESTER. -2121 the 13th century, but, in doing this, no provision was made being a memorial to Dean Chandler, inserted by the to distribute the pressure on the piers and walls adjacent, parishioners of All Saint.s, 1\Iarylebone, London. The glass with the result that the Norman tower piers were actually in the cathedral generally displays the condition and gradual being crushed by the superincumbent weight, and the con improvement in the art during a long period, the new win tinued vibration of the spire, under the action of the wind, dows in the Lady chapel furnishing admirable examples of no doubt assisted in disintegrating the materials and hasten modern work. ingthe great catastrophe,which occurred at half-past onep.m. The elegant Early English porch in the south aisle, added on Thursday, 21st J<'eb. 1861, when the whole tower and by Bishop Seffrid, gives access to the cloisters, the position spire, violently beaten upon by a great storm of wind from the of which, lying eastward under the choir, is altogether un N.E. and N.W. descended perpendicularly into the church, usual ; they are Perpendicular in style, and irregular in plan, destroying in its fall the tower arches with their piers, with west, south and east walks, the latter opening into the the entire eastern bay of the nave, and the greater part retro-choir ; over a door in the south walk is a shield of arms of the western bay of the choir, the spire, however, of Henry VII. marking the former house of one of the King's singularly retaining its upright position to the very last. -

Gerhard Von Wesel's Newsletter from England, 17 April 1471

Gerhard von Wesel’s Newsletter from England, 17 April 1471 HANNES KLEINEKE From the perspective of the modern scholar, one of the more fascinating aspects of the political crisis of 1470-71 is the existence of a number of closely contemporary ‘eye-witness’ accounts of events in England. Several of these accounts take the form of letters sent by diplomats or private individuals to the European continent or the English regions to transmit news of the latest developments.1 The best known of these newsletters were commissioned by the restored Edward IV himself,2 but others contain the independent (if sometimes badly informed) observations, which their authors reported – we must assume – in good faith. One of the most interesting of these accounts, not least because of its distinctive perspective, is that sent to the authorities of the German city of Cologne by Gerhard von Wesel, a merchant of the Steelyard, the Hanseatic headquarters in London. It was first printed in the German original by Goswin, Freiherr von der Ropp, in 1890,3 and an English translation by Donald White was published by John Adair in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research in 1968.4 The newsletter’s author, Gerhard von Wesel,5 was born in about 1443 as the second of three sons of Hermann von Wesel (died 1484), a Cologne merchant trading in England from the later 1420s.6 It is possible that the boy’s parents initially intended him for a clerical or academic career, since he received a degree of formal education and by the age of about fourteen had enrolled at the university of Cologne. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

King Richard III at York in Late Summer 1483 A. COMPTON REEVES The spring and summer of 1483 were times of high drama in the political life of England. King Edward IV died at Westminster Palace on 9 April seemingly of natural (but difficult to identify) causes following an illness of less than a fort- I night.‘ He was a few days short of his forty-first birthday. It was presumed that Edward, the older of his two sons, would become the next king as Edward V, and that there would be a minority government for the immediate future. That was not to be the case. The young Edward, Prince of Wales, aged twelve, was at Ludlow, the administrative centre of the principality of Wales, when his father died. There was insufficient time for Edward to be notified of his father’s death and to make a speedy journey east for the elaborate funeral rites and the final interment on 20 April of the remains of his father in the fine chapel of St George that Edward IV had caused to be constructed at Windsor. Prince Edward heard of his father’s death on or about 14 April,2 and he set off for London some ten days later. King Edward’s sole living brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was at Middleham Castle in Yorkshire when Edward died, and he began travelling towards London at about the same time as his nephew. Richard, it is appropriate to believe, anticipated that he would be taking on the duties of protector of England until his nephew should come of age and take up the full responsibilities of kingship, as Edward IV is reported to have directed, although no documentary proof of Edward’s wishes survives. -

Saints on Earth Final Text 21/9/04 3:39 Pm Page I

Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page i Saints on Earth Let saints on earth in concert sing With those whose work is done For all the servants of our king In heaven and earth are one. Charles Wesley Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page ii Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page iii Saints on Earth A biographical companion to Common Worship John H Darch Stuart K Burns Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page iv Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel:020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7898 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4036 1 Published 2004 by Church House Publishing Copyright © John H. Darch and Stuart K. Burns 2004 The Common Worship Calendar is copyright © The Archbishops’ Council, 2000 – 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, Church House Publishing, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ email: [email protected]. Printed in England by iv Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page v Contents Introduction vii Calendar of Saints 1 The Common Worship Calendar – Holy Days 214 Index of Names 226 v Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page vi To the staff and students of St John’s College, Nottingham – past, present and future Saints on Earth final text 21/9/04 3:39 pm Page vii Introduction In using the word ‘saint’ to described those commemorated in the Holy Days of the Common Worship calendar we are, of course, using it as a shorthand term. -

Kingsbury and Allied Families

KINGSBURY AND ALLIED FAMILIES A GENEALOGICAL STUDY WITH BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES Compiled and Privately Printed for MISS ALICE E. KINGSBURY BY THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY, Inc. NEW YORK 193 ◄ To FreJe:iri(Qk John King§huiry 1 of W atell'llmll'y, C oll'.lllllledicut, A Schoftall' all'.lld G entleman, W ho Made the Study of Family Records a Pastime anJ W ove That Study and interest Info H is Life illll a Clb.airming W ay Never to be F oirgottellll, And to His Sollll, FireJ.eiridk John Kingshuiry 9 J:ir.9 of N ew H aven, Connecticut, Who Combined the Traits of His Fa.their's Progenitors with the Spontane_ous Warmth of Those of H is M other, A iathea Ruth ScoviH Kingshury Contents,_ PAGE Kingsbury 7 Scovill 31 Leavenworth 42 Johnson 47 Bunnell 53 First Clark Line 59 Dayton 63 Conkling 67 Schellinger 72 First Peck Line 79 Kitchell 85 Sheaffe 87 Dorman 92 Bronson 95 Humiston IOI Todd 106 Tuttle II3 Southmayd I I9 Root 123 Ellis 126 HiH 130 Second Clark Line 1 35 Stone 138 Denison 144 Ayer 148 Davies 152 Foote 160 Second Peck Line 167 Sutliff 172 Brockett 178 Hotchkiss 183 5 CONTENTS PAGE First Cooper Line 190 Chatterton 195 Lamson 198 King 206 Noble 2Il Dewey 215 Hawley 219 Uffoot 224 Curtiss 229 Booth 235 \Vheeler 245 Nichols 2 49 Hickox 256 Baldwin 261 Richards 266 \Velton 271 Upson 2 74 Andrews 276 Index· of Families 281 6 DAYTON SOUTHMEAD SCHELLING ER (.SOUTHMAYD) Kingsbury INGSBURY is an ancient English patronymic that dates back to the time of the Saxon Kings.