Convocations Called by Edward IV and Richard of Gloucester in 1483: Did They Ever Take Place?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

Parish of Skipton*

294 HISTORY OF CRAVEN. PARISH OF SKIPTON* HAVE reserved for this parish, the most interesting part of my subject, a place in Wharfdale, in order to deduce the honour and fee of Skipton from Bolton, to which it originally belonged. In the later Saxon times Bodeltone, or Botltunef (the town of the principal mansion), was the property of Earl Edwin, whose large possessions in the North were among the last estates in the kingdom which, after the Conquest, were permitted to remain in the hands of their former owners. This nobleman was son of Leofwine, and brother of Leofric, Earls of Mercia.J It is somewhat remarkable that after the forfeiture the posterity of this family, in the second generation, became possessed of these estates again by the marriage of William de Meschines with Cecilia de Romille. This will be proved by the following table:— •——————————;——————————iLeofwine Earl of Mercia§=j=......... Leofric §=Godiva Norman. Edwin, the Edwinus Comes of Ermenilda=Ricardus de Abrineis cognom. Domesday. Goz. I———— Matilda=.. —————— I Ranulph de Meschines, Earl of Chester, William de Meschines=Cecilia, daughter and heir of Robert Romille, ob. 1129. Lord of Skipton. But it was before the Domesday Survey that this nobleman had incurred the forfeiture; and his lands in Craven are accordingly surveyed under the head of TERRA REGIS. All these, consisting of LXXVII carucates, lay waste, having never recovered from the Danish ravages. Of these-— [* The parish is situated partly in the wapontake of Staincliffe and partly in Claro, and comprises the townships of Skipton, Barden, Beamsley, Bolton Abbey, Draughton, Embsay-with-Eastby, Haltoneast-with-Bolton, and Hazlewood- with-Storithes ; and contains an area of 24,7893. -

James Sands of Block Island

HERALDIC DESCRIPTION ARMS: Or, a fesse dancettee between three cross-crosslets fitchee gules. CREST: A griffin segreant per fesse or and gules. MoITo: Probum non poenitet. DESCENDANTS OF JAMES SANDS OF BLOCK ISLAND With notes on the WALKER, HUTCHINSON, RAY, GUTHRIE, PALGRAVE, CORNELL, AYSCOUGH, MIDDAGH, HOLT, AND HENSHAW FAMILIES Compiled by MALCOLM SANDS WILSON Privately Printed New York • 1949 Copyright 1949 by Malcolm Sands Wilson 770 Park Avenue, New York 21, N. Y. All rights reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The William Byrd Press, Inc., Richmond, Virginia Foreword The purpose of this Genealogy of the Sands Family, which is the result of much research, is to put on record a more comprehensive account than any so far published in this country. The "Descent of Comfort Sands & of his Children," by Temple Prime, New York, 1886; and "The Direct Forefathers and All the Descendants of Richardson Sands, etc.," by Benjamin Aymar Sands, New York, 1916, (from both of which volumes I have obtained material) are excellent as far as they go, but their scope is very limited, as was the intention of their com pilers. I have not attempted to undertake a full and complete genealogy of this family, but have endeavored to fill certain lines and bring more nearly to date the data collected by the late Fanning C. T. Beck and the late LeBaron Willard, (brother-in-law of my aunt Caroline Sands Willard). I take this opportunity to express my thanks to all members of the family who have rendered cheerful and cooperative assistance. It had been my intention to have a Part II in this volume, in which the English Family of Sands, Sandes, Sandis or Sandys were to have been treated, and where the connecting link between James Sands of Block Island and his English forebears was to be made clear. -

Parish Churches in the Diocese of Rochester, C. 1320-C. 1520

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society PARISH CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER, c. 1320 - c. 1520 COLIN FLIGHT The core of this article is an alphabetical list of the parish churches belonging to the diocese of Rochester in the fifteenth century. Their distribution is shown by the accompanying map (Fig. 1). More precisely, the list as it stands describes the situation existing c. 1420; but information is also provided which will enable the reader to modify the list so that it describes the situation existing at any other chosen date between c. 1320 and c. 1520. Though many of the facts reported here may seem sufficiently well-known, the author is not aware of any previously published list which can claim to be both comprehensive in scope and accurate in detail. The information given below is all taken from primary sources, or, failing that, from secondary sources closely dependent on the primary sources. Where there is some uncertainty, this is stated. Apart from these admittedly doubtful points, the list is believed to be perfectly reliable. Readers who notice any errors or who can shed any further light on the areas of uncertainty should kindly inform the author. Before anything else, it needs to be understood that a large part of the diocese of Rochester did not come under the bishop's jurisdict- ion. More than thirty parishes, roughly one quarter of the total number, were subject to the archbishop of Canterbury. They constit- uted what was called the deanery of Shoreham. -

Journal of Arizona History Index

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, W-Z Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) W WAACs 36:318; 48:12 photo of 36:401 WAAFs 36:318 Wabash Cattle Company 33:35, 38 Wachholtz, Florence, book edited by, reviewed 18:381-82 Waco Tap 38:136 Wacos (airplanes) 15:334, 380 Waddell, Jack O., book coedited by, reviewed 22:273-74 Waddle, Billy 42:36, 38 Wade, Abner, photo of 28:297 property of 28:284, 286, 288, 294 Wade, Benjamin F. 19:202; 41:267, 274, 279, 280, 281, 282, 284 photo of 41:268 Wade, George A. 22:24 Wade Hampton Mine 23:249-50 Wade, James F. 14:136; 29:170 Wade, John Franklin IV(1)6 Wade, Michael S., book by, listed 24:297 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, W-Z Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 Wade, Nicholas 31:365, 397 n. 34 Wade, William 43:282 Wadleigh, Atherton B. 20:35-36, 56, 58-59 portrait 20:57 Wadsworth, B. C. 27:443 Wadsworth, Craig 41:328 Wadsworth mine 34:151 Wadsworth mining claim 34:122, 123 Wadsworth, Mr. See Wordsworth, William C. Wadsworth, Nevada 54:389 Wadsworth, William R. V(4)2 Wadsworth, William W. 23:21, 23 Waffle, Edison D. 7:20 n. 26 Wager, Evelyn 39:234 n. 1, 234 n. -

Lisa L. Ford Phd Thesis

CONCILIAR POLITICS AND ADMINISTRATION IN THE REIGN OF HENRY VII Lisa L. Ford A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2001 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7121 This item is protected by original copyright Conciliar Politics and Administration in the Reign of Henry VII Lisa L. Ford A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of St. Andrews April 2001 DECLARATIONS (i) I, Lisa Lynn Ford, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 100,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. Signature of candidate' (ii) I was admitted as a reseach student in January 1996 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in January 1997; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between 1996 and 2001. / 1 Date: ') -:::S;{:}'(j. )fJ1;;/ Signature of candidate: 1/ - / i (iii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date \ (If (Ls-> 1 Signature of supervisor: (iv) In submitting this thesis to the University of St. -

Ricardian Bulletin March 2020 Text Layout 1

ARTICLES Part 1. THE FATE OF THE SONS OF KING EDWARD IV: Robert Willoughby’s urgent mission PHILIPPA LANGLEY Robert Willoughby (1452–1502, made 1st Baron Willoughby de Broke c.1491) is a person of interest for The Missing Princes Project. He commanded the force despatched north by Henry VII immediately following the defeat of Richard III at the battle of Bosworth. Willoughby was charged with securing the children of the House of York, domiciled in the former king’s Yorkshire heartland, and escorting the Yorkist heir (or heirs) to London. As his lands lay in the south-west, Willoughby was not the most obvious choice for this mission, but his later interest in the northern Neville Latimer patrimony might suggest a motive.1 Willoughby had proved himself in military affairs and in 1501 was given command of a similarly significant commission when he conducted the 15-year-old Princess Catherine of Aragon from Plymouth to London for her marriage to Henry VII’s heir, Prince Arthur.2 At this remove we have no information regarding informing Vergil, who had potentially seen the boy Willoughby’s orders at Leicester other than that offered (and/or knew his age), were so profoundly mistaken. more than 30 years later by Henry VII’s historian Indeed, the eldest son of Edward IV would have Polydore Vergil: reached his majority on his fourteenth birthday,8 2 November 1484,9 and, as a result, would have been After Henry had obtained power, from the very start of his reign he then set about quelling the insurrections. -

Historical Introduction

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION. THE Manuscript volume from which this work of the Camden Society is derived has been long known as a record of great value: and has been quoted as such by several of the most inquiring and painstaking of our historical writers. Having come into the collection of the founder of the Harleian Library, so highly was its importance estimated by Humphrey Wanley, his librarian, that he described it at greater length than any other to which he eva- de voted his attention. His account of its contents occupies no fewer than sixty-five pages of the folio Catalogue of the Harleian Manu- scripts (vol. i. pp. 256-311). It was found, however, some years ago, on comparison of this calendar with the book itself, that it was far from presenting a complete view of the whole contents of the Manuscript, many entries being arbitrarily passed over, in the pro- portion of nearly two-fifths. In consequence it was thought desirable, with a view to an improved Catalogue of the Harleian Collection, which was then in contemplation, to make a fresh abstract of the volume. This was executed in the Manuscript Department of the British Museum in the year 1835; and, as there was no immediate prospect of its being printed, it was made accessible to the public by being classed as the Additional MS. 11,269. This latter book, however, being a mere abstract, page by page, unprovided with any index, is not at present of the least utility, except perhaps to a reader who might require assistance in his attempts to decypher the original. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

INDULGENCES and SOLIDARITY in LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND By

INDULGENCES AND SOLIDARITY IN LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND by ANN F. BRODEUR A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Copyright by Ann F. Brodeur, 2015 Indulgences and Solidarity in Late Medieval England Ann F. Brodeur Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Medieval indulgences have long had a troubled public image, grounded in centuries of confessional discord. Were they simply a crass form of medieval religious commercialism and a spiritual fraud, as the reforming archbishop Cranmer charged in his 1543 appeal to raise funds for Henry VIII’s contributions against the Turks? Or were they perceived and used in a different manner? In his influential work, Indulgences in Late Medieval England: Passports to Paradise, R.N. Swanson offered fresh arguments for the centrality and popularity of indulgences in the devotional landscape of medieval England, and thoroughly documented the doctrinal development and administrative apparatus that grew up around indulgences. How they functioned within the English social and devotional landscape, particularly at the local level, is the focus of this thesis. Through an investigation of published episcopal registers, my thesis explores the social impact of indulgences at the diocesan level by examining the context, aims, and social make up of the beneficiaries, as well as the spiritual and social expectations of the granting bishops. It first explores personal indulgences given to benefit individuals, specifically the deserving poor and ransomed captives, before examining indulgences ii given to local institutions, particularly hospitals and parishes. Throughout this study, I show that both lay people and bishops used indulgences to build, reinforce or maintain solidarity and social bonds between diverse groups. -

MFB (PDF , 39Kb)

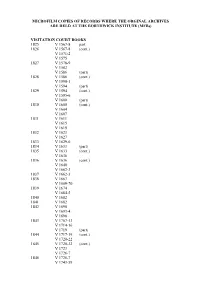

MICROFILM COPIES OF RECORDS WHERE THE ORGINAL ARCHIVES ARE HELD AT THE BORTHWICK INSTITUTE (MFBs) VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1825 V 1567-8 part 1826 V 1567-8 (cont.) V 1571-2 V 1575 1827 V 1578-9 V 1582 V 1586 (part) 1828 V 1586 (cont.) V 1590-1 V 1594 (part) 1829 V 1594 (cont.) V 1595-6 V 1600 (part) 1830 V 1600 (cont.) V 1604 V 1607 1831 V 1611 V 1615 V 1619 1832 V 1623 V 1627 1833 V 1629-0 1834 V 1633 (part) 1835 V 1633 (cont.) V 1636 1836 V 1636 (cont.) V 1640 V 1662-3 1837 V 1662-3 1838 V 1667 V 1669-70 1839 V 1674 V 1684-5 1840 V 1682 1841 V 1682 1842 V 1690 V 1693-4 V 1698 1843 V 1707 -13 V 1714-16 V 1719 (part) 1844 V 1717-19 (cont.) V 1720-22 1845 V 1720-22 (cont.) V 1723 V 1726-7 1846 V 1726-7 V 1743-59 1847 V 1743 (V Book and Papers) V 1748-9 (V Papers) 1848 V 1748-9 (V Book) V 1759-60 (V Book, Papers) 1849 V 1764 (C Book, Ex Book, Papers) V 1770 (part C Book) 1850 V 1770 (cont., CB) V 1777 (C. Book, Papers) V 1781 (Exh Book) 1851 V 1781 (CB and Papers) V 1786 (Papers) 1852 V 1786 (cont., CB) V 1791 (Papers) V 1809 (Call Book and Papers) V 1817 (Call Book) 1853 V 1817, cont. (Call Book) V 1825 (Call Book and Papers) V 1841 (Papers) 1854 V 1841 (Papers cont) V 1849 (Call Book and Papers) V 1853 (Call Book and Papers) CLEVELAND VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1855 C/V/CB. -

York Minster Conservation Management Plan 2021

CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOL. 2 GAZETTEERS DRAFT APRIL 2021 Alan Baxter YORK MINSTER CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VOL. 2 GAZETTEERS PREPARED FOR THE CHAPTER OF YORK DRAFT APRIL 2021 HOW TO USE THIS DOCUMENT This document is designed to be viewed digitally using a number of interactive features to aid navigation. These features include bookmarks (in the left-hand panel), hyperlinks (identified by blue text) to cross reference between sections, and interactive plans at the beginning of Vol III, the Gazetteers, which areAPRIL used to locate individual 2021 gazetteer entries. DRAFT It can be useful to load a ‘previous view’ button in the pdf reader software in order to retrace steps having followed a hyperlink. To load the previous view button in Adobe Acrobat X go to View/Show/ Hide/Toolbar Items/Page Navigation/Show All Page Navigation Tools. The ‘previous view’ button is a blue circle with a white arrow pointing left. York Minster CMP / April 2021 DRAFT Alan Baxter CONTENTS CONTENTS Introduction to the Gazetteers ................................................................................................ i Exterior .................................................................................................................................... 1 01: West Towers and West Front ................................................................................. 1 02: Nave north elevation ............................................................................................... 7 03: North Transept elevations....................................................................................