Targeting BRAF and RAS in Colorectal Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application of a MYC Degradation

SCIENCE SIGNALING | RESEARCH ARTICLE CANCER Copyright © 2019 The Authors, some rights reserved; Application of a MYC degradation screen identifies exclusive licensee American Association sensitivity to CDK9 inhibitors in KRAS-mutant for the Advancement of Science. No claim pancreatic cancer to original U.S. Devon R. Blake1, Angelina V. Vaseva2, Richard G. Hodge2, McKenzie P. Kline3, Thomas S. K. Gilbert1,4, Government Works Vikas Tyagi5, Daowei Huang5, Gabrielle C. Whiten5, Jacob E. Larson5, Xiaodong Wang2,5, Kenneth H. Pearce5, Laura E. Herring1,4, Lee M. Graves1,2,4, Stephen V. Frye2,5, Michael J. Emanuele1,2, Adrienne D. Cox1,2,6, Channing J. Der1,2* Stabilization of the MYC oncoprotein by KRAS signaling critically promotes the growth of pancreatic ductal adeno- carcinoma (PDAC). Thus, understanding how MYC protein stability is regulated may lead to effective therapies. Here, we used a previously developed, flow cytometry–based assay that screened a library of >800 protein kinase inhibitors and identified compounds that promoted either the stability or degradation of MYC in a KRAS-mutant PDAC cell line. We validated compounds that stabilized or destabilized MYC and then focused on one compound, Downloaded from UNC10112785, that induced the substantial loss of MYC protein in both two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cell cultures. We determined that this compound is a potent CDK9 inhibitor with a previously uncharacterized scaffold, caused MYC loss through both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms, and suppresses PDAC anchorage- dependent and anchorage-independent growth. We discovered that CDK9 enhanced MYC protein stability 62 through a previously unknown, KRAS-independent mechanism involving direct phosphorylation of MYC at Ser . -

Comparative Analysis of Protein Expression Concomitant with DNA Methyltransferase 3A Depletion in a Melanoma Cell Line

American Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2011, 2, 539-572 doi:10.4236/ajac.2011.25064 Published Online September 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajac) Comparative Analysis of Protein Expression Concomitant with DNA Methyltransferase 3A Depletion in a Melanoma Cell Line Shengnan Tang1,#, Xiaoyan Liu1,#, Tonghua Li1*, Haoyue Wang2, Jiangming Sun1, Qian Qiao1, Jun Yao3, Jian Fei2 1Department of Chemistry, Tongji University, Shanghai, China 2School of Life Science & Technology, Tongji University, Shanghai, China 3School of Medicine, Fudan University, Shanghai, China E-mail: *[email protected] Received March 17, 2011; revised May 3, 2011; accepted June 1, 2011 Abstract DNA methyltransferase 3A (Dnmt3a), a de novo methyltransferase, has attracted a great deal of attention for its important role played in tumorigenesis. We have previously demonstrated that melanoma is unable to grow in-vivo in conditions of Dnmt3a depletion in a mouse model. In this study, we cultured the Dnmt3a depletion B16 melanoma (Dnmt3a-D) cell line to conduct a comparative analysis of protein expression con-comitant with Dnmt3a depletion in a melanoma cell line. After two-dimensional separation, by gel elec- tro-phoresis and liquid chromatography, combined with mass spectrometry analysis (1DE-LC-MS/MS), the re-sults demonstrated that 467 proteins were up-regulated and 535 proteins were down-regulated in the Dnmt3a-D cell line compared to the negative control (NC) cell line. The Genome Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathway were used to further analyze the altered proteins. KEGG pathway analysis indicated that the MAPK signaling pathway exhibited a greater alteration in proteins, an interesting finding due to the close rela- tion-ship with tumorigenesis. -

Modulation of NF-Κb Signalling by Microbial Pathogens

REVIEWS Modulation of NF‑κB signalling by microbial pathogens Masmudur M. Rahman and Grant McFadden Abstract | The nuclear factor-κB (NF‑κB) family of transcription factors plays a central part in the host response to infection by microbial pathogens, by orchestrating the innate and acquired host immune responses. The NF‑κB proteins are activated by diverse signalling pathways that originate from many different cellular receptors and sensors. Many successful pathogens have acquired sophisticated mechanisms to regulate the NF‑κB signalling pathways by deploying subversive proteins or hijacking the host signalling molecules. Here, we describe the mechanisms by which viruses and bacteria micromanage the host NF‑κB signalling circuitry to favour the continued survival of the pathogen. The nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) family of transcription Signalling targets upstream of NF‑κB factors regulates the expression of hundreds of genes that NF-κB proteins are tightly regulated in both the cyto- are associated with diverse cellular processes, such as pro- plasm and the nucleus6. Under normal physiological liferation, differentiation and death, as well as innate and conditions, NF‑κB complexes remain inactive in the adaptive immune responses. The mammalian NF‑κB cytoplasm through a direct interaction with proteins proteins are members of the Rel domain-containing pro- of the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) family, including IκBα, tein family: RELA (also known as p65), RELB, c‑REL, IκBβ and IκBε (also known as NF-κBIα, NF-κBIβ and the NF-κB p105 subunit (also known as NF‑κB1; which NF-κBIε, respectively); IκB proteins mask the nuclear is cleaved into the p50 subunit) and the NF-κB p100 localization domains in the NF‑κB complex, thus subunit (also known as NF‑κB2; which is cleaved into retaining the transcription complex in the cytoplasm. -

Characterization of the Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitor SU11248 (Sunitinib/ SUTENT in Vitro and in Vivo

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Genetik Characterization of the Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitor SU11248 (Sunitinib/ SUTENT in vitro and in vivo - Towards Response Prediction in Cancer Therapy with Kinase Inhibitors Michaela Bairlein Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ. -Prof. Dr. K. Schneitz Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. A. Gierl 2. Hon.-Prof. Dr. h.c. A. Ullrich (Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen) 3. Univ.-Prof. A. Schnieke, Ph.D. Die Dissertation wurde am 07.01.2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 19.04.2010 angenommen. FOR MY PARENTS 1 Contents 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3 Zusammenfassung .................................................................................................................................................... 6 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 4.1 Cancer .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Systems Pharmacology Dissection of Epimedium Targeting Tumor Microenvironment to Enhance Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Responses in Lung Cancer

www.aging-us.com AGING 2021, Vol. 13, No. 2 Research Paper Systems pharmacology dissection of Epimedium targeting tumor microenvironment to enhance cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in lung cancer Chao Huang1,*, Zhihua Li2,*, Jinglin Zhu2, Xuetong Chen1, Yuanyuan Hao2, Ruijie Yang2, Ruifei Huang2, Jun Zhou3, Zhenzhong Wang3, Wei Xiao3, Chunli Zheng2, Yonghua Wang1,2 1Bioinformatics Center, College of Life Sciences, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China 2Key Laboratory of Resource Biology and Biotechnology in Western China, Ministry of Education, School of Life Sciences, Northwest University, Xi’an 710069, China 3State Key Laboratory of New-Tech for Chinese Medicine Pharmaceutical Process, Jiangsu Kanion Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Lianyungang 222001, China *Equal contribution Correspondence to: Yonghua Wang, Chunli Zheng, Wei Xiao; email: [email protected]; [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9552-8040; [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8809-9137 Keywords: systems pharmacology, NSCLC, tumor microenvironment, epimedium, icaritin Received: April 15, 2020 Accepted: October 1, 2020 Published: January 17, 2021 Copyright: © 2021 Huang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT The clinical notably success of immunotherapy fosters an enthusiasm in developing drugs by enhancing antitumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Epimedium, is a promising herbal medicine for tumor immunotherapy due to the pharmacological actions in immunological function modulation and antitumor. Here, we developed a novel systems pharmacology strategy to explore the polypharmacology mechanism of Epimedium involving in targeting TME of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). -

![MAPK14 (T106M) [GST-Tagged] Kinase](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9439/mapk14-t106m-gst-tagged-kinase-1959439.webp)

MAPK14 (T106M) [GST-Tagged] Kinase

MAPK14 (T106M) [GST-tagged] Kinase Alternate Names: Cytokine-Suppressive Anti-inflammatory Drug-Binding Protein 1, CSBP1, SAPK2A, p38-Alpha Cat. No. 66-0035-050 Quantity: 50 µg Lot. No. 30314 Storage: -70˚C FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY NOT FOR USE IN HUMANS CERTIFICATE OF ANALYSIS Page 1 of 2 Background Physical Characteristics Protein ubiquitylation and protein Species: human Protein Sequence: Please see page 2 phosphorylation are the two major mechanisms that regulate the func- Source: E. coli tions of proteins in eukaryotic cells. Quantity: 50 μg However, these different posttrans- lational modifications do not operate Concentration: 3.55 mg/ml independently of one another, but are frequently interlinked to enable bio- Formulation: 50 mM Tris/HCl pH7.5, 0.1 mM EGTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% ß-Mercap- logical processes to be controlled in a toethanol, 270 mM sucrose, 0.03% Brij-35, more complex and sophisticated man- 1 mM Benzamidine, 0.2 mM PMSF ner. Studying how protein phosphory- lation events control the ubiquitin sys- Molecular Weight: ~67.6 kDa tem and how ubiquitylation regulates Purity: >85% by InstantBlue™ SDS-PAGE protein phosphorylation has become a focal point of the study of cell regula- Stability/Storage: 12 months at -70˚C; tion and human disease. MAP kinas- aliquot as required es are serine, threonine, and tyrosine specific protein kinases that regulate proliferation, gene expression, differ- entiation, mitosis, cell survival, and Quality Assurance apoptosis in response to stimuli, such Purity: Protein Identification: as mitogens, osmotic stress, heat 4-12% gradient SDS-PAGE Confirmed by mass spectrometry. shock and pro-inflammatory cytok- InstantBlue™ staining ines. -

Association of Cyclin Dependent Kinase 10 and Transcription Factor

www.nature.com/scientificreports There are amendments to this paper OPEN Association of Cyclin Dependent Kinase 10 and Transcription Factor 2 during Human Corneal Epithelial Received: 20 February 2019 Accepted: 25 July 2019 Wound Healing in vitro model Published: xx xx xxxx Meraj Zehra1,2, Shamim Mushtaq1, Syed Ghulam Musharraf3,4, Rubina Ghani5 & Nikhat Ahmed1,6 Proper wound healing is dynamic in order to maintain the corneal integrity and transparency. Impaired or delayed corneal epithelial wound healing is one of the most frequently observed ocular defect and difcult to treat. Cyclin dependen kinase (cdk), a known cell cycle regulator, required for proper proliferating and migration of cell. We therefore investigated the role of cell cycle regulator cdk10, member of cdk family and its functional association with transcriptional factor (ETS2) at active phase of corneal epithelial cell migration. Our data showed that cdk10 was associated with ETS2, while its expression was upregulated at the active phase (18 hours) of cell migration and gradually decrease as the wound was completely closed. Topical treatment with anti-cdk10 and ETS2 antibodies delayed the wound closure time at higest concentration (10 µg/ml) compared to control. Further, our results also showed increased mRNA expression of cdk10 and ETS2 at active phase of migration at approximately 2 fold. Collectively, our data reveals that cdk10 and ETS2 efciently involved during corneal wound healing. Further studies are warranted to better understand the mechanism and safety of topical cdk10 and ETS2 proteins in corneal epithelial wound-healing and its potential role for human disease treatment. Corneal epithelial injuries and burns produce extensive damage to the ocular surface epithelium and may cause signifcant loss of function1. -

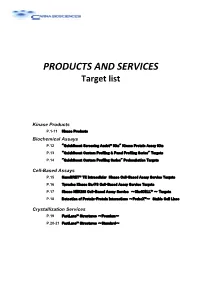

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain -

Brain-Restricted Mtor Inhibition with Binary Pharmacology 2 3 Ziyang Zhang1, Qiwen Fan2,3, Xujun Luo2,3, Kevin J

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.12.336677; this version posted October 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Brain-Restricted mTOR Inhibition with Binary Pharmacology 2 3 Ziyang Zhang1, Qiwen Fan2,3, Xujun Luo2,3, Kevin J. Lou1, William A. Weiss2,3,4,5, Kevan 4 M. Shokat1,* 5 6 1 Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology and Howard Hughes Medical 7 Institute, University of California, San Francisco, California 8 2 Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, San Francisco, California 9 3 Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, California 10 4 Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Francisco, California 11 5 Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, California 12 * Corresponding author. [email protected] (K.M.S.). 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.12.336677; this version posted October 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 13 Abstract 14 On-target-off-tissue drug engagement is an important source of adverse effects 15 that constrains the therapeutic window of drug candidates. In diseases of the central 16 nervous system, drugs with brain-restricted pharmacology are highly desirable. -

Intrinsic Resistance to PIM Kinase Inhibition in AML Through P38α-Mediated Feedback Activation of Mtor Signaling

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 7, No. 25 Priority Research Paper Intrinsic resistance to PIM kinase inhibition in AML through p38α-mediated feedback activation of mTOR signaling Diede Brunen1, María José García-Barchino2, Disha Malani3,*, Noorjahan Jagalur Basheer4,*, Cor Lieftink1, Roderick L. Beijersbergen1, Astrid Murumägi3, Kimmo Porkka5, Maija Wolf3, C. Michel Zwaan4, Maarten Fornerod4, Olli Kallioniemi3, José Ángel Martínez-Climent2 and René Bernards1 1 Division of Molecular Carcinogenesis, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Division of Oncology, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain 3 Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM), University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 4 Department of Pediatric Oncology, Erasmus Medical Center/Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands 5 Hematology Research Unit Helsinki, Department of Medicine, Helsinki University Central Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland * These authors have contributed equally to this work Correspondence to: René Bernards, email: [email protected] Keywords: AML, PIM, AZD1208, p38, resistance Received: April 06, 2016 Accepted: May 23, 2016 Published: June 05, 2016 ABSTRACT Although conventional therapies for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) are effective in inducing remission, many patients relapse upon treatment. Hence, there is an urgent need for novel therapies. PIM kinases are often overexpressed in AML and DLBCL and are therefore an attractive therapeutic target. However, in vitro experiments have demonstrated that intrinsic resistance to PIM inhibition is common. It is therefore likely that only a minority of patients will benefit from single agent PIM inhibitor treatment. In this study, we performed an shRNA-based genetic screen to identify kinases whose suppression is synergistic with PIM inhibition. -

In Silico Molecular Target Prediction Unveils

In silico molecular target prediction unveils mebendazole as a potent MAPK14 inhibitor Jeremy Ariey-bonnet, Kendall Carrasco, Marion Le Grand, Laurent Hoffer, Stéphane Betzi, Mikael Feracci, Philipp Tsvetkov, François Devred, Yves Collette, Xavier Morelli, et al. To cite this version: Jeremy Ariey-bonnet, Kendall Carrasco, Marion Le Grand, Laurent Hoffer, Stéphane Betzi, et al.. In silico molecular target prediction unveils mebendazole as a potent MAPK14 inhibitor. Molecular Oncology, Elsevier, 2020, 14, pp.3083 - 3099. 10.1002/1878-0261.12810. hal-02989358 HAL Id: hal-02989358 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02989358 Submitted on 15 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License In silico molecular target prediction unveils mebendazole as a potent MAPK14 inhibitor Jeremy Ariey-Bonnet1 , Kendall Carrasco1, Marion Le Grand1 , Laurent Hoffer1 ,Stephane Betzi1 , Mikael Feracci1,†, Philipp Tsvetkov2, Francois Devred2 , Yves Collette1 , Xavier Morelli1 , Pedro Ballester1 and Eddy Pasquier1 1 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Medicale (INSERM), Institut Paoli Calmettes, Centre de Recherche en Cancerologie de Marseille (CRCM), Aix Marseille Universite, France 2 CNRS, UMR 7051, INP, Inst Neurophysiopathol, Fac Pharm, Aix Marseille Universite, France Keywords The concept of polypharmacology involves the interaction of drug mole- cancer; drug target prediction; glioblastoma; cules with multiple molecular targets. -

MAPK14 Antibody (Y323) Peptide Affinity Purified Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (Pab) Catalog # Ap7226d

9765 Clairemont Mesa Blvd, Suite C San Diego, CA 92124 Tel: 858.875.1900 Fax: 858.622.0609 MAPK14 Antibody (Y323) Peptide Affinity Purified Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (Pab) Catalog # AP7226d Specification MAPK14 Antibody (Y323) - Product Information Application FC, WB,E Primary Accession Q16539 Other Accession P47811 Reactivity Human, Mouse, Rat Host Rabbit Clonality Polyclonal Isotype Rabbit Ig Calculated MW 41293 Antigen Region 301-330 MAPK14 Antibody (Y323) - Additional Information Overlay histogram showing Hela cells stained Gene ID 1432 with AP7226d (green line). The cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (10 min) and then Other Names permeabilized with 90% methanol for 10 min. Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14, MAP The cells were then icubated in 2% bovine kinase 14, MAPK 14, Cytokine suppressive serum albumin to block non-specific anti-inflammatory drug-binding protein, protein-protein interactions followed by the CSAID-binding protein, CSBP, MAP kinase antibody (AP7226d, 1:25 dilution) for 60 min at MXI2, MAX-interacting protein 2, 37ºC. The secondary antibody used was Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 alpha, Goat-Anti-Rabbit IgG, DyLight® 488 MAP kinase p38 alpha, Stress-activated Conjugated Highly Cross-Adsorbed(OH191631) protein kinase 2a, SAPK2a, MAPK14, CSBP, at 1/400 dilution for 40 min at 37ºC. Isotype CSBP1, CSBP2, CSPB1, MXI2, SAPK2A control antibody (blue line) was rabbit IgG (1μg/1x10^6 cells) used under the same Target/Specificity conditions. Acquisition of >10, 000 events was This MAPK14 antibody is generated from performed. rabbits immunized with a KLH conjugated synthetic peptide between 301-330 amino acids from human MAPK14. Dilution FC~~1:25 WB~~1:1000 Format Purified polyclonal antibody supplied in PBS with 0.09% (W/V) sodium azide.