Microaggressions and Marginality Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caring for People with Multiple Disabilities : an Interdisciplinary Guide for Caregivers Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CARING FOR PEOPLE WITH MULTIPLE DISABILITIES : AN INTERDISCIPLINARY GUIDE FOR CAREGIVERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cindy French | 145 pages | 29 Mar 1995 | Elsevier Health Sciences | 9780761647058 | English | San Antonio, United States Caring for People with Multiple Disabilities : An Interdisciplinary Guide for Caregivers PDF Book She earned her Ph. Companionship is key to a trusted relationship with our caregivers. Now we get to reconnect a few times a month. Depending on the covered benefits and reimbursement policies of State Medicaid programs, including those provided through waivers, other services may be available to some patients. She later joined the Office of the Center Director as a senior advisor leading and supporting various strategic initiatives such as Clinical Trials Innovation, Real World Evidence, and efforts to improve diversity and inclusion in medical product development. Caregivers in the focus groups consistently reported they did not have time to take care of their own health. We constructed a composite measure of self-care or mobility disability that reflects whether the older adult received help in the prior month with 1 or more self-care eg, eating, dressing, bathing, and toileting or mobility eg, getting outside, getting around inside, and getting out of bed activities. Parents and caregivers should aim to have children be as independent as possible. Care Services. Facilitator Feedback Facilitators agreed that the pilot program went smoothly overall. Training and Education in Professional Psychology , 1 2 , — doi Additionally, the program provides advocacy for residents transitioning from nursing homes back to the community through Money Follows the Person. Compensation for the extra effort involved in caring for patients with complex needs is clearly important. -

Text Editing in UNIX: an Introduction to Vi and Editing

Text Editing in UNIX A short introduction to vi, pico, and gedit Copyright 20062009 Stewart Weiss About UNIX editors There are two types of text editors in UNIX: those that run in terminal windows, called text mode editors, and those that are graphical, with menus and mouse pointers. The latter require a windowing system, usually X Windows, to run. If you are remotely logged into UNIX, say through SSH, then you should use a text mode editor. It is possible to use a graphical editor, but it will be much slower to use. I will explain more about that later. 2 CSci 132 Practical UNIX with Perl Text mode editors The three text mode editors of choice in UNIX are vi, emacs, and pico (really nano, to be explained later.) vi is the original editor; it is very fast, easy to use, and available on virtually every UNIX system. The vi commands are the same as those of the sed filter as well as several other common UNIX tools. emacs is a very powerful editor, but it takes more effort to learn how to use it. pico is the easiest editor to learn, and the least powerful. pico was part of the Pine email client; nano is a clone of pico. 3 CSci 132 Practical UNIX with Perl What these slides contain These slides concentrate on vi because it is very fast and always available. Although the set of commands is very cryptic, by learning a small subset of the commands, you can edit text very quickly. What follows is an outline of the basic concepts that define vi. -

Nothing About Us Without Us Exhibition Large Print Text 18Pt

Nothing About Us Without Us Exhibition Large Print Text 18pt 1 Contents Introduction…………………………………………….4 Timeline………………………………………………...5 Banners……………………………………………….22 Photographs and Posters………………………......24 Placards by Jo Ann Taylor.........…………………...27 T-shirt and Other Campaign Materials Case……...28 Leaflets, Badges and Campaign Materials Case…29 Cased T-Shirts………………………………………. 35 Protest Placards…………………………………….. 36 The Autistic Rights Movement…………………….. 37 No Excuses…………………………………………. 46 Pure Art Studio……………………………………… 48 One Voice…………………………………………… 50 Quiet Riot……………………………………………. 51 Music………………………………………………… 66 2 Nothing About Us Without Us Playlist……………. 67 Interviews……………………………………………. 68 3 Introduction panel This exhibition is the second stage in a long-term project that looks at the representation of disabled people. The museum is working with groups, campaigners and individuals to capture their stories and re-examine how the history of disabled people’s activism is presented. We encourage you to let us know if you have any comments, objects or stories you would like to share to help to continue to tell this story. If you are interested in sharing your object or story as part of this project, please speak to a member of staff or contact [email protected] 4 Timeline The timeline on the wall is split into five sections: Early Days, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s and 2010s. Each section has an introductory label followed by photographs and labels with further information. Beneath the timeline is a shelf with pencils and pieces of card on it that visitors can use to write their own additions to the timeline and leave them on the shelf for other visitors to see. The introduction to the timeline is as follows: Is anything missing? Add to the timeline using the cards and shelf. -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets............................................................................................................. -

Course Bidding at Business Schools

Course Bidding at Business Schools Authors: Tayfun Sönmez, M. Ünver This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Working Papers in Economics, 2005 Originally posted on: http://ideas.repec.org/p/boc/bocoec/618.html Course Bidding at Business Schools∗ Tayfun S¨onmez Ko¸cUniversity and M. Utku Unver¨ Ko¸cUniversity Abstract Mechanisms that rely on course bidding are widely used at Business Schools in order to allocate seats at oversubscribed courses. Bids play two key roles under these mechanisms: Bids are used to infer student preferences and bids are used to determine who have bigger claims on course seats. We show that these two roles may easily conßict and preferences induced from bids may signiÞcantly differ from the true preferences. Therefore while these mechanisms are promoted as market mechanisms, they do not necessarily yield market out- comes. The two conßicting roles of bids is a potential source of efficiency loss part of which can be avoided simply by asking students to state their preferences in addition to bidding and thus “separating” the two roles of the bids. While there may be multiple market outcomes under this proposal, there is a market outcome which Pareto dominates any other market outcome. ∗We would like to thank seminar participants at London Business School and SITE 2003 Workshop on Matching Markets for their insightful comments. S¨onmez gratefully acknowledges the research support of Ko¸cBank via the Ko¸cBank scholar program and Turkish Academy of Sciences in the framework of the Young Scientist Award Program via grant TS/TUBA-GEB¨ IP/2002-1-19.ú Any errors are our own responsibility. -

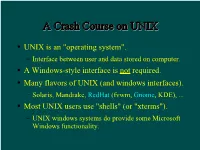

A Crash Course on UNIX

AA CCrraasshh CCoouurrssee oonn UUNNIIXX UNIX is an "operating system". Interface between user and data stored on computer. A Windows-style interface is not required. Many flavors of UNIX (and windows interfaces). Solaris, Mandrake, RedHat (fvwm, Gnome, KDE), ... Most UNIX users use "shells" (or "xterms"). UNIX windows systems do provide some Microsoft Windows functionality. TThhee SShheellll A shell is a command-line interface to UNIX. Also many flavors, e.g. sh, bash, csh, tcsh. The shell provides commands and functionality beyond the basic UNIX tools. E.g., wildcards, shell variables, loop control, etc. For this tutorial, examples use tcsh in RedHat Linux running Gnome. Differences are minor for the most part... BBaassiicc CCoommmmaannddss You need these to survive: ls, cd, cp, mkdir, mv. Typically these are UNIX (not shell) commands. They are actually programs that someone has written. Most commands such as these accept (or require) "arguments". E.g. ls -a [show all files, incl. "dot files"] mkdir ASTR688 [create a directory] cp myfile backup [copy a file] See the handout for a list of more commands. AA WWoorrdd AAbboouutt DDiirreeccttoorriieess Use cd to change directories. By default you start in your home directory. E.g. /home/dcr Handy abbreviations: Home directory: ~ Someone else's home directory: ~user Current directory: . Parent directory: .. SShhoorrttccuuttss To return to your home directory: cd To return to the previous directory: cd - In tcsh, with filename completion (on by default): Press TAB to complete filenames as you type. Press Ctrl-D to print a list of filenames matching what you have typed so far. Completion works with commands and variables too! Use ↑, ↓, Ctrl-A, & Ctrl-E to edit previous lines. -

Legislative Advocacy Priorities Guide

Legislative & Advocacy Priorities Guide Summer 2018 A Message from the Executive Director I am pleased to announce the release of the summer edition of the National Council on Independent Living’s 2018 Policy Priorities. This publication will introduce you to a sample of the many legislative issues NCIL is currently pursuing in order to secure full inclusion and equality for people with disabilities in our great nation. I would like to draw particular attention to issues surrounding Independent Living funding. CILs and their statewide counterparts are the only organizations directly working to address the issues outlined in this publication. They use shoe-string budgets to successfully advocate for individuals with disabilities facing discrimination while fighting to win an even playing field and ensure the civil and human rights of all Americans. I am very proud of our community’s hard work to bring these issues to Congress. Together we will see the passage of our legislative priorities, the restoration of our civil rights, and a world in which people with disabilities are truly valued equally and participate fully. Kelly Buckland Table of Contents The Independent Living Program → Pages 4 - 6 Healthcare and Long-Term Services and Supports → Pages 6 - 11 Disability Integration Act Reform Medicaid, Don’t Gut It! Independent Living and Medicaid Healthcare Money Follows the Person Durable Medical Equipment (DME) and Complex Rehabilitation Technology (CRT) Prohibiting Discrimination Based on Disability in Healthcare Opioids and Chronic Pain Electronic Visit Verification (EVV) Assisted Suicide → Pages 11 - 14 House Concurrent Resolution 80 Against Assisted Suicide Laws Civil Rights and the Americans with Disabilities Act → Pages 14 - 15 ADA Education and Reform Act of 2017: H.R. -

Introduction to Unix Shell (Part I)

Introduction to Unix shell (part I) Evgeny Stambulchik Faculty of Physics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel Joint ICTP-IAEA School on Atomic Processes in Plasmas February 27 – March 3, 2017 Trieste, Italy Contrary to popular belief, Unix is user friendly. It just happens to be very selective about who it decides to make friends with. Unknown Initially used at Bell Labs, but soon licensed to academy (notably, U. of California, Berkeley) and commercial vendors (IBM, Sun, etc). There are two major products that came out of Berkeley: LSD and Unix. We don’t believe this to be a coincidence. Jeremy S. Anderson, Unix systems administrator Historical overview (kind of) Unix is a family of multiuser, multitasking operating systems stemming from the original Unix developed in the 1970’s at Bell Labs by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie1, and others. Some consider Unix to be the second most important invention to come out of AT&T Bell Labs after the transistor. Dennis Ritchie 1Also famous for creating the C programming language. Historical overview (kind of) Unix is a family of multiuser, multitasking operating systems stemming from the original Unix developed in the 1970’s at Bell Labs by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie1, and others. Some consider Unix to be the second most important invention to come out of AT&T Bell Labs after the transistor. Dennis Ritchie Initially used at Bell Labs, but soon licensed to academy (notably, U. of California, Berkeley) and commercial vendors (IBM, Sun, etc). There are two major products that came out of Berkeley: LSD and Unix. -

BARRIERS and OPPORTUNITIES for DOCTORS with DISABILITIES Alicia Ouellette*

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NVJ\13-3\NVJ302.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-JUN-13 12:56 PATIENTS TO PEERS: BARRIERS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR DOCTORS WITH DISABILITIES Alicia Ouellette* In May 2012, the National Disability Rights Network issued a report enti- tled Devaluing People with Disabilities: Medical Procedures That Violate Civil Rights.1 The report is an indictment of a health care system that fails to recog- nize the value of life with disability, despite the importance of the health care system in the lives of people with disabilities. The report describes conversa- tions between doctors and persons with disabilities and their families in which people with disabilities are “viewed as having little value as they are. They are considered not as fully human, endowed with inalienable rights of liberty, pri- vacy and the right to be left alone—solely because they were born with a disa- bility.”2 The National Disability Rights Network is hardly the first group or individual to criticize American medicine for its treatment of persons with disa- bilities.3 Disability scholars have documented a long history of medical mis- treatment of and insensitivity toward people with disabilities at the hands of the medical establishment,4 and individuals with disabilities have authored compel- * Professor of Law and Associate Dean, Albany Law School. Many thanks to Philip Zazove, Christopher Moreland, Demetrius Moutsiakis, and the members of the Drexel Law Faculty workshop for their thoughtful feedback on this paper. Thanks also to Sevil Nuredinoski for her research assistance. 1 DAVID CARLSON, CINDY SMITH & NACHAMA WILKER, DEVALUING PEOPLE WITH DISABILI- TIES: MEDICAL PROCEDURES THAT VIOLATE CIVIL RIGHTS (2012), available at http://www. -

Comparative Studies of 10 Programming Languages Within 10 Diverse Criteria Revision 1.0

Comparative Studies of 10 Programming Languages within 10 Diverse Criteria Revision 1.0 Rana Naim∗ Mohammad Fahim Nizam† Concordia University Montreal, Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada Quebec, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Sheetal Hanamasagar‡ Jalal Noureddine§ Concordia University Montreal, Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada Quebec, Canada [email protected] [email protected] Marinela Miladinova¶ Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada [email protected] Abstract This is a survey on the programming languages: C++, JavaScript, AspectJ, C#, Haskell, Java, PHP, Scala, Scheme, and BPEL. Our survey work involves a comparative study of these ten programming languages with respect to the following criteria: secure programming practices, web application development, web service composition, OOP-based abstractions, reflection, aspect orientation, functional programming, declarative programming, batch scripting, and UI prototyping. We study these languages in the context of the above mentioned criteria and the level of support they provide for each one of them. Keywords: programming languages, programming paradigms, language features, language design and implementation 1 Introduction Choosing the best language that would satisfy all requirements for the given problem domain can be a difficult task. Some languages are better suited for specific applications than others. In order to select the proper one for the specific problem domain, one has to know what features it provides to support the requirements. Different languages support different paradigms, provide different abstractions, and have different levels of expressive power. Some are better suited to express algorithms and others are targeting the non-technical users. The question is then what is the best tool for a particular problem. -

Unix-And-Radiance.Pdf

UNIX and RADIANCE Giulio Antonutto & Andrew McNeil Unix Terminal 3 Starting the Terminal Application 3 Useful Unix Commands 3 Wildcard Characters 4 Directory Characters 4 Process control 4 Pipes and Redirection 4 Shell Redirection Operators 5 Makefile 5 X11 - X Window Server 7 Launching X11 7 The First Time 7 SCRIPTING 8 HOW TO START 8 HOW TO CONTINUE 9 Create the file ‘run’ 9 Give the proper permissions 9 Run the new tool 9 Future 9 UNIX and RADIANCE 2 Unix Terminal Starting the Terminal Application On a Mac the terminal program can be found in the /Applications/Utilities folder. When launched a window titled “Terminal - Bash - 80 x 24” will appear. This window contains a Unix prompt (which is in some ways similar to a DOS prompt for those familiar with windows). At the prompt you can type commands that will be executed within the terminal window. Useful Unix Commands The following UNIX commands will allow the user to navigate through the file system, manipulate files, check and terminate running processes. Command Description Usage Useful options ls list directory contents ls -l lists additional file info ls folder/ -a lists all files (including hidden files) cd change directory cd folder/folder2/ cd .. more view a text file one page at a time more file.txt cp copy file cp file.txt newfile.txt mv move a file mv oldloc.txt newloc..txt rm remove a file rm file DANGER, DO NOT USE: rm * ps list currently running processes ps top list the currently running processes top -u -s 5 5 and various system statistic UNIX and RADIANCE 3 Command Description Usage Useful options kill kills a running process kill pid pid is the process id number which can be found by using ps. -

National Disability Policy: a Progress Report, November 1, 1997-October 31, 1998

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 428 496 EC 307 100 TITLE National Disability Policy: A Progress Report, November 1, 1997-October 31, 1998. INSTITUTION National Council on Disability, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1999-02-16 NOTE 66p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council on Disability, 1331 F Street, NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20004-1107; Tel: 202-272-2004; TTY: 202-272-2074; Fax: 202-272-2022; Web site: http://www.ncd.gov PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; Assistive Devices (for Disabled); Children; Civil Rights Legislation; *Disabilities; Educational Legislation; Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; Employment; *Federal Legislation; *Government Role; Health Services; Housing; Program Effectiveness; Research Needs; *Social Integration; Transportation IDENTIFIERS *Americans with Disabilities Act 1990; Individuals with Disabilities Education Act ABSTRACT This progress report reviews federal policy activities toward the inclusion, empowerment, and independence of people with disabilities consistent with the vision of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). The report covers the period of November 1, 1997, through October 31, 1998. It notes progress where it has occurred and makes further recommendations in the following areas:(1) disability research;(2) civil rights;(3) education;(4) health care;(5) long-term services and supports; (6) immigrants, and racial and ethnic minorities with disabilities;(7) Social Security work incentives and Social Security solvency;(8) employment;