The Sumatran Rhino Is One-Of-A-Kind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular and Functional Evolution of Hemoglobin in Perissodactyl

Molecular and functional evolution of hemoglobin in perissodactyl mammals (equids, tapirs, and rhinos) by Margaret Clapin A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada © 2019 Abstract: In this thesis, the oxygen binding characteristics of recombinant hemoglobin (Hb) isoforms (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2 [α2δ2]) from the extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are compared with Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) and black rhino (Diceros bicornis) Hb. The major Hb component (HbA) of horses (Equus caballus) was also examined, as its blood O2 affinity has a low thermal sensitivity. This trait is commonly associated with cold-adaptation as it permits O2 to be offloaded at the cool peripheral tissues of regionally endothermic mammals, though the mechanism(s) by which the oxygenation enthalpy is reduced in horse Hb is unknown. It was hypothesized that the woolly rhino Hb isoforms would have similarly low thermal sensitivities to that of horses, either through enhanced effector binding or by altering the energetic transition from the tense to the relaxed state of hemoglobin. To test this hypothesis the hemoglobin coding sequences for each of the above species were determined and their Hb isoforms expressed using E. coli and purified. Oxygen equilibrium curves were then determined in the presence and absence of allosteric effectors at 25 and 37°C. Horse HbA had a low sensitivity to 2,3- diphosphoglycerate (DPG), though its low temperature sensitivity was primarily driven by increased DPG binding at the lower test temperature. -

Impacts of African Elephant Feeding on White Rhinoceros Foraging Opportunities

Impacts of African elephant feeding on white rhinoceros foraging opportunities Dominique Prinsloo Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Science at Nelson Mandela University October 2017 Supervisors: Professor Graham I. H. Kerley Associate Professor Joris P. G. M. Cromsigt DECLARATION FULL NAME: Dominique Prinsloo STUDENT NUMBER: s215376668 DEGREE: Master of Science DECLARATION: In accordance with Rule G5.6.3, I hereby declare that this dissertation is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. SIGNATURE: DATE: 11 October 2017 i CONTENTS DECLARATION I CONTENTS II SUMMARY IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V CHAPTER 1: GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 Functional Diversity of Megaherbivores 1 White Rhinos as Ecosystem Engineers 2 Elephants as Ecosystem Engineers 3 The Megaherbivore-Megaherbivore Interaction 5 Aims, Objectives and Hypotheses 7 CHAPTER 2: EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF AFRICAN ELEPHANT FEEDING ON THE FORAGING BEHAVIOUR OF OTHER HERBIVORES 9 INTRODUCTION 9 METHODS 11 Study Site 11 Experimental Design and Sampling 12 Levels of Impact 12 Experiment 13 Camera Trapping 14 Data Analyses 16 Effect of Woody Debris on Visitation 16 Effect of CWD on Behaviour 16 RESULTS 17 Effect of Woody Debris on Visitation 18 Effect of Woody Debris on Foraging Behaviour 21 DISCUSSION 25 Conclusion 27 CHAPTER 3: EVALUATING THE EFFECTS OF ELEPHANT-DEPOSITED WOODY DEBRIS ON THE STRUCTURE OF GRAZING LAWNS 28 INTRODUCTION 28 METHODS 30 Study -

Ancient Metaproteomics: a Novel Approach for Understanding Disease And

Ancient metaproteomics: a novel approach for understanding disease and diet in the archaeological record Jessica Hendy PhD University of York Archaeology August, 2015 ii Abstract Proteomics is increasingly being applied to archaeological samples following technological developments in mass spectrometry. This thesis explores how these developments may contribute to the characterisation of disease and diet in the archaeological record. This thesis has a three-fold aim; a) to evaluate the potential of shotgun proteomics as a method for characterising ancient disease, b) to develop the metaproteomic analysis of dental calculus as a tool for understanding both ancient oral health and patterns of individual food consumption and c) to apply these methodological developments to understanding individual lifeways of people enslaved during the 19th century transatlantic slave trade. This thesis demonstrates that ancient metaproteomics can be a powerful tool for identifying microorganisms in the archaeological record, characterising the functional profile of ancient proteomes and accessing individual patterns of food consumption with high taxonomic specificity. In particular, analysis of dental calculus may be an extremely valuable tool for understanding the aetiology of past oral diseases. Results of this study highlight the value of revisiting previous studies with more recent methodological approaches and demonstrate that biomolecular preservation can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of ancient proteins as an archaeological tool for this characterisation. Using the approaches developed in this study we have the opportunity to increase the visibility of past diseases and their aetiology, as well as develop a richer understanding of individual lifeways through the production of molecular life histories. iii iv List of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... -

Timeline of the Evolutionary History of Life

Timeline of the evolutionary history of life This timeline of the evolutionary history of life represents the current scientific theory Life timeline Ice Ages outlining the major events during the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes development of life on planet Earth. In P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs biology, evolution is any change across Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda successive generations in the heritable -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion characteristics of biological populations. o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ← Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity o Earliest animals ←Earliest plants at every level of biological organization, i Multicellular -1000 — c from kingdoms to species, and individual life ←Sexual reproduction organisms and molecules, such as DNA and – P proteins. The similarities between all present r -1500 — o day organisms indicate the presence of a t – e common ancestor from which all known r Eukaryotes o species, living and extinct, have diverged -2000 — z o through the process of evolution. More than i Huron ian – c 99 percent of all species, amounting to over ←Oxygen crisis [1] five billion species, that ever lived on -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Earth are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current – Photosynthesis Pong ola species range from 10 million to 14 -3000 — A million,[4] of which about 1.2 million have r c been documented and over 86 percent have – h [5] e not yet been described. However, a May a -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen 2016 -

An Act Prohibiting the Import, Sale and Possession of African Elephants, Lions, Leopards, Black Rhinoceros, White Rhinoceros and Giraffes

Substitute Senate Bill No. 925 Public Act No. 21-52 AN ACT PROHIBITING THE IMPORT, SALE AND POSSESSION OF AFRICAN ELEPHANTS, LIONS, LEOPARDS, BLACK RHINOCEROS, WHITE RHINOCEROS AND GIRAFFES. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Assembly convened: Section 1. (NEW) (Effective October 1, 2021) (a) For purposes of this section, "big six African species" means any specimen of any of the following members of the animal kingdom: African elephant (loxodonta africana), African lion (panthera leo), African leopard (panthera pardus pardus), black rhinoceros (diceros bicornis), white rhinoceros (ceratotherium simum cottoni) and African giraffe (giraffa camelopardalis), including any part, product or offspring thereof, or the dead body or parts thereof, except fossils, whether or not it is included in a manufactured product or in a food product. (b) No person shall import, possess, sell, offer for sale or transport in this state any big six African species. (c) Any law enforcement officer shall have authority to enforce the provisions of this section and, whenever necessary, to execute any warrant to search for and seize any big six African species imported, possessed, sold, offered for sale or transported in violation of this section. Substitute Senate Bill No. 925 (d) The provisions of subsection (b) of this section shall not apply if the possession of such specimen of a big six African species is expressly authorized by any federal law or permit, or if any of the following conditions exist that are not otherwise prohibited -

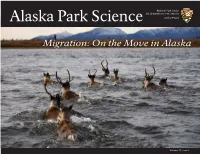

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

Captive Breeding of Mammals - Marco Masseti

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT – Vol. II – Captive Breeding of Mammals - Marco Masseti CAPTIVE BREEDING OF MAMMALS Marco Masseti Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Laboratori di Antropologia, Università di Firenze, Firenze, Italy Keywords: captive breeding, domestic mammals, threatened wild mammals, zoological gardens, arks, museums. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Captive breeding of mammals. The domestic species. 3. Selective breeding 4. Captive breeding of non-domestic species as a conservation strategy. 5. Captive breeding of threatened species 6. Captive breeding of threatened micromammals 7. Captive breeding and reintroduction of carnivores 8. Case studies 8.1 The Arabian Oryx Programme 8.2 The Case Of The Fallow Deer 9. Perspectives Bibliography Biographical Sketch 1. Introduction Mammals are currently among the main victims of human depredations on the environment. A huge amount of species and subspecies have disappeared to date, revealing human exploitation of natural resources as a long lasting process beginning in prehistorical periods and lasting until historical times. In the late Pleistocene, for example, the modern mammalian fauna assemblages of the Western Palaearctic Region were already defined. They would have yet comprised the totality of the species still surviving today, if some extinctions had not mainly affected large terrestrial mammals between 15.000UNESCO and 10.000 years BP, such –as the EOLSS mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach, 1803), the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus Rosenmuller & Heinroth, 1794), the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach, 1803), the giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus Berckhemer, 1910), and others. All these extinctions were without replacementSAMPLE by ecologically similar species:CHAPTERS for large mammals - i.e. species exceeding about 40 kg mean adult body weight - it has been estimated that Europe lost approximately 7 out of 24 genera (i.e. -

Detomidine and Butorphanol for Standing Sedation in a Range of Zoo-Kept Ungulate Species

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 48(3): 616–626, 2017 Copyright 2017 by American Association of Zoo Veterinarians DETOMIDINE AND BUTORPHANOL FOR STANDING SEDATION IN A RANGE OF ZOO-KEPT UNGULATE SPECIES Tim Bouts, D.V.M., M.Sc., Dip. E.C.Z.M., Joanne Dodds, V.N., Karla Berry, V.N., Abdi Arif, M.V.Sc., Polly Taylor, Vet. M. B., Ph. D., Dip. E.C.V.A.A., Andrew Routh, B. V. Sc., Cert. Zoo. Med., and Frank Gasthuys, D.V.M., Ph. D., Dip. E.C.V.A.A. Abstract: General anesthesia poses risks for larger zoo species, like cardiorespiratory depression, myopathy, and hyperthermia. In ruminants, ruminal bloat and regurgitation of rumen contents with potential aspiration pneumonia are added risks. Thus, the use of sedation to perform minor procedures is justified in zoo animals. A combination of detomidine and butorphanol has been routinely used in domestic animals. This drug combination, administered by remote intramuscular injection, can also be applied for standing sedation in a range of zoo animals, allowing a number of minor procedures. The combination was successfully administered in five species of nondomesticated equids (Przewalski horse [Equus ferus przewalskii; n ¼ 1], onager [Equus hemionus onager; n ¼ 4], kiang [Equus kiang; n ¼ 3], Grevy’s zebra [Equus grevyi; n ¼ 4], and Somali wild ass [Equus africanus somaliensis; n ¼ 7]), with a mean dose range of 0.10–0.17 mg/kg detomidine and 0.07–0.13 mg/kg butorphanol; the white (Ceratotherium simum simum; n ¼ 12) and greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis; n ¼ 4), with a mean dose of 0.015 mg/kg of both detomidine and butorphanol; and Asiatic elephant bulls (Elephas maximus; n ¼ 2), with a mean dose of 0.018 mg/kg of both detomidine and butorphanol. -

The Rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and Their Nutrition

During the Pleistocene, there were three main groups of Im Pleistozän traten drei Hauptgruppen von Nashörnern auf, rhinoceroses, each of them in a different part of the Old jede in einem anderen Teil der Alten Welt: die afrikanische World: the African lineage leads to the modern square- Linie führt zu den heutigen Breitmaul- und Spitzmaulnashör- lipped rhinoceros and black rhinoceros, the Asian group nern, die asiatische Gruppe umfasst das Panzer-, das Suma- includes the great one-horned rhinoceros, the Sumatra tra- und das Javanashorn sowie ihre Vorfahren. Zur dritten rhinoceros and the Java rhinoceros as well as their ances- Gruppe, die im späten Pleistozän ausstarb, gehören Coelo- tors. The third group, which became extinct in the Late donta und Stephanorhinus. Das Wollhaarnashorn (Coelodonta Pleistocene, includes Coelodonta and Stephanorhinus. The antiquitatis) trat in Europa zum ersten Mal während der woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) appeared in Elsterkaltzeit auf. Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis, das Wald- Europe for the first time during the Elsterian cold period. nashorn, ist auf die Interglaziale beschränkt und wanderte Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis, the forest rhinoceros, is lim- wahrscheinlich nach jeder Kaltzeit erneut von Asien aus ein. ited to the interglacial periods and probably dispersed again Das Steppennashorn (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus) ist wie- and again after each cold period from Asia into Europe. The derum in Europa seit 450 000 Jahren heimisch. In Neumark- steppe rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus) again has Nord konnten diese drei Nashörner zusammen nachgewiesen been present in Europe for 450,000 years. All three types werden, was umso bemerkenswerter ist, weil das Wollhaar- of rhinoceros together could be documented in Neumark- nashorn im Allgemeinen als Vertreter der Glazialfaunen gilt. -

Bill Analysis for File Copy

OLR Bill Analysis sSB 925 AN ACT PROHIBITING THE IMPORT, SALE AND POSSESSION OF AFRICAN ELEPHANTS, LIONS, LEOPARDS, BLACK RHINOCEROS, WHITE RHINOCEROS AND GIRAFFES. SUMMARY This bill generally bans importing, possessing, selling, offering for sale, or transporting in Connecticut a specimen (dead or alive) of any of six types of African animals, which the bill collectively refers to as the “big six African species.” It applies to certain elephants, lions, leopards, giraffes, and two rhinoceros species. The bill establishes a graduated penalty structure for violations, ranging from no penalty for someone who, unaware and in good faith, violates the ban, to a class D felony for someone with at least two prior violations subject to penalty. In all cases, the bill requires seizing the specimen and any other property or item used in connection with the violation. The specimen, property, or item is then forfeited and, unless the specimen is alive, destroyed. The bill contains several exemptions, including for a specimen that is already legally in the state or distributed to a beneficiary or heir, as long as the owner or distributee timely obtains a certificate of possession from the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP). The ban also does not apply to fossils and ivory and the following under certain conditions: circuses; museums; zoological institutions; and motion picture, television, or digital media production companies. Lastly, the bill specifies that the ban does not prohibit transporting through the state endangered or threatened species subject to the terms of another state’s permit, which existing law allows. The United States regulates the trade of the species covered by the Researcher: KLM Page 1 5/8/21 2021SB-00925-R010637-BA.DOCX bill, except the African giraffe, through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and laws such as the Endangered Species Act (16 U.S.C. -

Natsca News Issue 22-1.Pdf

http://www.natsca.org NatSCA News Title: The Horns of Dilemma: The Impact of Illicit Trade in Rhino Horn Author(s): Paolo Viscardi Source: Viscardi, P. (2012). The Horns of Dilemma: The Impact of Illicit Trade in Rhino Horn. NatSCA News, Issue 22, 8 ‐ 13. URL: http://www.natsca.org/article/107 NatSCA supports open access publication as part of its mission is to promote and support natural science collections. NatSCA uses the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ for all works we publish. Under CCAL authors retain ownership of the copyright for their article, but authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy articles in NatSCA publications, so long as the original authors and source are cited. NatSCA News Issue 22 The Horns of a Dilemma: The Impact of the Illicit Trade in Rhino Horn Paolo Viscardi Deputy Keeper, Horniman Museum and Gardens Email: [email protected] Abstract Rhinoceros horn has recently become highly sought after on the black market for use in Traditional Asian Medicine. Demand has increased levels of poaching and has led to the theft of material from collections across Europe through 2011. This article provides background to the situation and reiterates guidance on protecting both rhinoceros horn and staff in natural science collections. Keywords Rhinoceros, rhino, horn, poaching, security, theft, auction, legislation, threat, CITES, DEFRA, AHVLA Introduction It has been a bad year for rhinoceros and for natural history collections holding their horn. The international black market dealing in rhino horn has been particularly active recently, following a rumour that Traditional Asian Medicine (TAM) containing powdered horn could successfully treat and prevent cancer.