The Rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and Their Nutrition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Large Terrestrial Carnivores on Pleistocene Ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Matthew W

The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on SPECIAL FEATURE Pleistocene ecosystems Blaire Van Valkenburgha,1, Matthew W. Haywardb,c,d, William J. Ripplee, Carlo Melorof, and V. Louise Rothg aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095; bCollege of Natural Sciences, Bangor University, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW, United Kingdom; cCentre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa; dCentre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; eTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; fResearch Centre in Evolutionary Anthropology and Palaeoecology, School of Natural Sciences and Psychology, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool L3 3AF, United Kingdom; and gDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0338 Edited by Yadvinder Malhi, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 6, 2015 (received for review February 28, 2015) Large mammalian terrestrial herbivores, such as elephants, have analogs, making their prey preferences a matter of inference, dramatic effects on the ecosystems they inhabit and at high rather than observation. population densities their environmental impacts can be devas- In this article, we estimate the predatory impact of large (>21 tating. Pleistocene terrestrial ecosystems included a much greater kg, ref. 11) Pleistocene carnivores using a variety of data from diversity of megaherbivores (e.g., mammoths, mastodons, giant the fossil record, including species richness within guilds, pop- ground sloths) and thus a greater potential for widespread habitat ulation density inferences based on tooth wear, and dietary in- degradation if population sizes were not limited. -

Molecular and Functional Evolution of Hemoglobin in Perissodactyl

Molecular and functional evolution of hemoglobin in perissodactyl mammals (equids, tapirs, and rhinos) by Margaret Clapin A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada © 2019 Abstract: In this thesis, the oxygen binding characteristics of recombinant hemoglobin (Hb) isoforms (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2 [α2δ2]) from the extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are compared with Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) and black rhino (Diceros bicornis) Hb. The major Hb component (HbA) of horses (Equus caballus) was also examined, as its blood O2 affinity has a low thermal sensitivity. This trait is commonly associated with cold-adaptation as it permits O2 to be offloaded at the cool peripheral tissues of regionally endothermic mammals, though the mechanism(s) by which the oxygenation enthalpy is reduced in horse Hb is unknown. It was hypothesized that the woolly rhino Hb isoforms would have similarly low thermal sensitivities to that of horses, either through enhanced effector binding or by altering the energetic transition from the tense to the relaxed state of hemoglobin. To test this hypothesis the hemoglobin coding sequences for each of the above species were determined and their Hb isoforms expressed using E. coli and purified. Oxygen equilibrium curves were then determined in the presence and absence of allosteric effectors at 25 and 37°C. Horse HbA had a low sensitivity to 2,3- diphosphoglycerate (DPG), though its low temperature sensitivity was primarily driven by increased DPG binding at the lower test temperature. -

Evolution and Extinction of the Giant Rhinoceros Elasmotherium Sibiricum Sheds Light on Late Quaternary Megafaunal Extinctions

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0722-0 Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions Pavel Kosintsev1, Kieren J. Mitchell2, Thibaut Devièse3, Johannes van der Plicht4,5, Margot Kuitems4,5, Ekaterina Petrova6, Alexei Tikhonov6, Thomas Higham3, Daniel Comeskey3, Chris Turney7,8, Alan Cooper 2, Thijs van Kolfschoten5, Anthony J. Stuart9 and Adrian M. Lister 10* Understanding extinction events requires an unbiased record of the chronology and ecology of victims and survivors. The rhi- noceros Elasmotherium sibiricum, known as the ‘Siberian unicorn’, was believed to have gone extinct around 200,000 years ago—well before the late Quaternary megafaunal extinction event. However, no absolute dating, genetic analysis or quantita- tive ecological assessment of this species has been undertaken. Here, we show, by accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating of 23 individuals, including cross-validation by compound-specific analysis, that E. sibiricum survived in Eastern Europe and Central Asia until at least 39,000 years ago, corroborating a wave of megafaunal turnover before the Last Glacial Maximum in Eurasia, in addition to the better-known late-glacial event. Stable isotope data indicate a dry steppe niche for E. sibiricum and, together with morphology, a highly specialized diet that probably contributed to its extinction. We further demonstrate, with DNA sequencing data, a very deep phylogenetic split between the subfamilies Elasmotheriinae and Rhinocerotinae that includes all the living rhinoceroses, settling a debate based on fossil evidence and confirming that the two lineages had diverged by the Eocene. As the last surviving member of the Elasmotheriinae, the demise of the ‘Siberian unicorn’ marked the extinction of this subfamily. -

Ancient Metaproteomics: a Novel Approach for Understanding Disease And

Ancient metaproteomics: a novel approach for understanding disease and diet in the archaeological record Jessica Hendy PhD University of York Archaeology August, 2015 ii Abstract Proteomics is increasingly being applied to archaeological samples following technological developments in mass spectrometry. This thesis explores how these developments may contribute to the characterisation of disease and diet in the archaeological record. This thesis has a three-fold aim; a) to evaluate the potential of shotgun proteomics as a method for characterising ancient disease, b) to develop the metaproteomic analysis of dental calculus as a tool for understanding both ancient oral health and patterns of individual food consumption and c) to apply these methodological developments to understanding individual lifeways of people enslaved during the 19th century transatlantic slave trade. This thesis demonstrates that ancient metaproteomics can be a powerful tool for identifying microorganisms in the archaeological record, characterising the functional profile of ancient proteomes and accessing individual patterns of food consumption with high taxonomic specificity. In particular, analysis of dental calculus may be an extremely valuable tool for understanding the aetiology of past oral diseases. Results of this study highlight the value of revisiting previous studies with more recent methodological approaches and demonstrate that biomolecular preservation can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of ancient proteins as an archaeological tool for this characterisation. Using the approaches developed in this study we have the opportunity to increase the visibility of past diseases and their aetiology, as well as develop a richer understanding of individual lifeways through the production of molecular life histories. iii iv List of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... -

High Herbivore Density Associated with Vegetation Diversity in Interglacial Ecosystems

High herbivore density associated with vegetation diversity in interglacial ecosystems Christopher J. Sandoma,b,1, Rasmus Ejrnæsb, Morten D. D. Hansenc, and Jens-Christian Svenninga,1 aEcoinformatics and Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark; bWildlife Ecology, Biodiversity and Conservation, Department of Bioscience, Kalø, Aarhus University, DK-8410 Rønde, Denmark; cNatural History Museum Aarhus, DK-8000 Aarhus C, Denmark Edited by William J. Sutherland, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and accepted by the Editorial Board February 4, 2014 (received for review June 25, 2013) The impact of large herbivores on ecosystems before modern and the late Holocene (2,000–0yB.P.)(seeMaterials and Methods human activities is an open question in ecology and conservation. for further details). The Last Interglacial and Holocene periods For Europe, the controversial wood–pasture hypothesis posits that harbored temperate climates that allowed forest cover in the grazing by wild large herbivores supported a dynamic mosaic of region but with highly divergent assemblages of large herbivores vegetation structures at the landscape scale under temperate con- and under different human influences. The Last Interglacial had ditions before agriculture. The contrasting position suggests that 11 species of large herbivores (≥10 kg; Table S1) with a median European temperate vegetation was primarily closed forest with body weight of 524 kg (range, 19–6,500 kg), the largest being relatively small open areas, at most impacted locally by large her- Elephas antiquus (straight-tusked elephant) (Fig. 1), and no bivores. Given the role of modern humans in the world-wide dec- modern humans, because modern humans arrived in Europe only imations of megafauna during the late Quaternary, to resolve this 40–50,000 y ago (14). -

Timeline of the Evolutionary History of Life

Timeline of the evolutionary history of life This timeline of the evolutionary history of life represents the current scientific theory Life timeline Ice Ages outlining the major events during the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes development of life on planet Earth. In P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs biology, evolution is any change across Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda successive generations in the heritable -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion characteristics of biological populations. o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ← Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity o Earliest animals ←Earliest plants at every level of biological organization, i Multicellular -1000 — c from kingdoms to species, and individual life ←Sexual reproduction organisms and molecules, such as DNA and – P proteins. The similarities between all present r -1500 — o day organisms indicate the presence of a t – e common ancestor from which all known r Eukaryotes o species, living and extinct, have diverged -2000 — z o through the process of evolution. More than i Huron ian – c 99 percent of all species, amounting to over ←Oxygen crisis [1] five billion species, that ever lived on -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Earth are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current – Photosynthesis Pong ola species range from 10 million to 14 -3000 — A million,[4] of which about 1.2 million have r c been documented and over 86 percent have – h [5] e not yet been described. However, a May a -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen 2016 -

Employment Effects of Minimum Wages

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Neumark, David Article Employment effects of minimum wages IZA World of Labor Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Neumark, David (2018) : Employment effects of minimum wages, IZA World of Labor, ISSN 2054-9571, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, Iss. 6v2, http://dx.doi.org/10.15185/izawol.6.v2 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193409 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DAVID NEUMARK University of California—Irvine, USA, and IZA, Germany Employment effects of minimum wages When minimum wages are introduced or raised, are there fewer jobs? Keywords: minimum wage, employment effects ELEVATOR PITCH Percentage differences between US state and The potential benefits of higher minimum wages come federal minimum wages, 2018 from the higher wages for affected workers, some of 80 whom are in poor or low-income families. -

Last Interglacial (MIS 5) Ungulate Assemblage from the Central Iberian Peninsula: the Camino Cave (Pinilla Del Valle, Madrid, Spain)

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 374 (2013) 327–337 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Last Interglacial (MIS 5) ungulate assemblage from the Central Iberian Peninsula: The Camino Cave (Pinilla del Valle, Madrid, Spain) Diego J. Álvarez-Lao a,⁎, Juan L. Arsuaga b,c, Enrique Baquedano d, Alfredo Pérez-González e a Área de Paleontología, Departamento de Geología, Universidad de Oviedo, C/Jesús Arias de Velasco, s/n, 33005 Oviedo, Spain b Centro Mixto UCM-ISCIII de Evolución y Comportamiento Humanos, C/Sinesio Delgado, 4, 28029 Madrid, Spain c Departamento de Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad Universitaria, 28040 Madrid, Spain d Museo Arqueológico Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid, Plaza de las Bernardas, s/n, 28801-Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain e Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), Paseo Sierra de Atapuerca, s/n, 09002 Burgos, Spain article info abstract Article history: The fossil assemblage from the Camino Cave, corresponding to the late MIS 5, constitutes a key record to un- Received 2 November 2012 derstand the faunal composition of Central Iberia during the last Interglacial. Moreover, the largest Iberian Received in revised form 21 January 2013 fallow deer fossil population was recovered here. Other ungulate species present at this assemblage include Accepted 31 January 2013 red deer, roe deer, aurochs, chamois, wild boar, horse and steppe rhinoceros; carnivores and Neanderthals Available online 13 February 2013 are also present. The origin of the accumulation has been interpreted as a hyena den. Abundant fallow deer skeletal elements allowed to statistically compare the Camino Cave fossils with other Keywords: Early Late Pleistocene Pleistocene and Holocene European populations. -

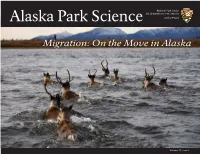

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Sędziowie I Prokuratorzy Skład Komisji Sądowych Rozpatrujących Zachodniopomorsko-Brandenburski Spór Z Przełomu Xv/Xvi

JACEK BRZUSTOWICZ (Choszczno) SĘDZIOWIE I PROKURATORZY SKŁAD KOMISJI SĄDOWYCH ROZPATRUJĄCYCH ZACHODNIOPOMORSKO-BRANDENBURSKI SPÓR Z PRZEŁOMU XV/XVI W., DOTYCZĄCY PRZYNALEŻNOŚCI PAŃSTWOWEJ GRANOWA NA ZIEMI CHOSZCZEŃSKIEJ Największe średniowieczne procesy sądowe mają swoje ważne miej- sce w badaniach historycznych1. Znalazły też odbicie w dotychczasowej historiografii Pomorza Zachodniego i Nowej Marchii2. Znaczenie po- znawcze mają także mniejsze procesy, które mogą znacznie wzbogacić naszą wiedzę3, jak w przypadku procesu pomorsko-brandenburskiego ———— 1 Dużą literaturę mają już procesy polsko-krzyżackie z początków XIV wieku: W. Sie- r a d z a n, Świadomość historyczna świadków w procesach polsko-krzyżackich w XIV i XV wieku, Toruń 1933; K. T y m i e n i e c k i, Proces polsko-krzyżacki z lat 1320-1321, „Przegląd Historyczny”, 21, 1918; H. C h ł o p o c k a, Tradycja o Pomorzu Gdańskim w zeznaniach świadków na procesach polsko-krzyżackich w XIV i XV wieku, „Roczniki Historyczne”, 25, 1959; Idem, Procesy Polski z zakonem krzyżackim w XIV wieku. Studium Źródłoznawcze, Poznań 1967; J. B i e n i a k, Środowisko świadków procesu polsko-krzyżackiego z 1339 r., [w:] J. B i e n i a k, Polskie rycerstwo średniowieczne. Wybór pism, Kraków 2002, s. 195-214. Interesujące są opracowania procesów wal- densów z Nowej Marchii i Pomorza zob. D. K u r z e, Quellen zur Ketzergeschichte Brandenburgs und Pommerns, Berlin 1975; W. S w o b o d a, Waldensi na Pomorzu Zachodnim i w Nowej Marchii w świetle protokołów szczecińskiej inkwizycji z lat 1392-1394, „Materiały Zachodniopomorskie”, t. XIX, Szczecin 1976, s. -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores.