Cave Bear, Cave Lion and Cave Hyena Skulls from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular and Functional Evolution of Hemoglobin in Perissodactyl

Molecular and functional evolution of hemoglobin in perissodactyl mammals (equids, tapirs, and rhinos) by Margaret Clapin A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada © 2019 Abstract: In this thesis, the oxygen binding characteristics of recombinant hemoglobin (Hb) isoforms (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2 [α2δ2]) from the extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are compared with Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) and black rhino (Diceros bicornis) Hb. The major Hb component (HbA) of horses (Equus caballus) was also examined, as its blood O2 affinity has a low thermal sensitivity. This trait is commonly associated with cold-adaptation as it permits O2 to be offloaded at the cool peripheral tissues of regionally endothermic mammals, though the mechanism(s) by which the oxygenation enthalpy is reduced in horse Hb is unknown. It was hypothesized that the woolly rhino Hb isoforms would have similarly low thermal sensitivities to that of horses, either through enhanced effector binding or by altering the energetic transition from the tense to the relaxed state of hemoglobin. To test this hypothesis the hemoglobin coding sequences for each of the above species were determined and their Hb isoforms expressed using E. coli and purified. Oxygen equilibrium curves were then determined in the presence and absence of allosteric effectors at 25 and 37°C. Horse HbA had a low sensitivity to 2,3- diphosphoglycerate (DPG), though its low temperature sensitivity was primarily driven by increased DPG binding at the lower test temperature. -

Ancient Metaproteomics: a Novel Approach for Understanding Disease And

Ancient metaproteomics: a novel approach for understanding disease and diet in the archaeological record Jessica Hendy PhD University of York Archaeology August, 2015 ii Abstract Proteomics is increasingly being applied to archaeological samples following technological developments in mass spectrometry. This thesis explores how these developments may contribute to the characterisation of disease and diet in the archaeological record. This thesis has a three-fold aim; a) to evaluate the potential of shotgun proteomics as a method for characterising ancient disease, b) to develop the metaproteomic analysis of dental calculus as a tool for understanding both ancient oral health and patterns of individual food consumption and c) to apply these methodological developments to understanding individual lifeways of people enslaved during the 19th century transatlantic slave trade. This thesis demonstrates that ancient metaproteomics can be a powerful tool for identifying microorganisms in the archaeological record, characterising the functional profile of ancient proteomes and accessing individual patterns of food consumption with high taxonomic specificity. In particular, analysis of dental calculus may be an extremely valuable tool for understanding the aetiology of past oral diseases. Results of this study highlight the value of revisiting previous studies with more recent methodological approaches and demonstrate that biomolecular preservation can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of ancient proteins as an archaeological tool for this characterisation. Using the approaches developed in this study we have the opportunity to increase the visibility of past diseases and their aetiology, as well as develop a richer understanding of individual lifeways through the production of molecular life histories. iii iv List of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... -

Timeline of the Evolutionary History of Life

Timeline of the evolutionary history of life This timeline of the evolutionary history of life represents the current scientific theory Life timeline Ice Ages outlining the major events during the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes development of life on planet Earth. In P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs biology, evolution is any change across Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda successive generations in the heritable -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion characteristics of biological populations. o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ← Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity o Earliest animals ←Earliest plants at every level of biological organization, i Multicellular -1000 — c from kingdoms to species, and individual life ←Sexual reproduction organisms and molecules, such as DNA and – P proteins. The similarities between all present r -1500 — o day organisms indicate the presence of a t – e common ancestor from which all known r Eukaryotes o species, living and extinct, have diverged -2000 — z o through the process of evolution. More than i Huron ian – c 99 percent of all species, amounting to over ←Oxygen crisis [1] five billion species, that ever lived on -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Earth are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current – Photosynthesis Pong ola species range from 10 million to 14 -3000 — A million,[4] of which about 1.2 million have r c been documented and over 86 percent have – h [5] e not yet been described. However, a May a -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen 2016 -

Pleistocene Panthera Leo Spelaea

Quaternaire, 22, (2), 2011, p. 105-127 PLEISTOCENE PANTHERA LEO SPELAEA (GOLDFUSS 1810) REMAINS FROM THE BALVE CAVE (NW GERMANY) – A CAVE BEAR, HYENA DEN AND MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC HUMAN CAVE – AND REVIEW OF THE SAUERLAND KARST LION CAVE SITES n Cajus G. DIEDRICH 1 ABSTRACT Pleistocene remains of Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss 1810) from Balve Cave (Sauerland Karst, NW-Germany), one of the most famous Middle Palaeolithic Neandertalian cave sites in Europe, and also a hyena and cave bear den, belong to the most im- portant felid sites of the Sauerland Karst. The stratigraphy, macrofaunal assemblages and Palaeolithic stone artefacts range from the final Saalian (late Middle Pleistocene, Acheulean) over the Middle Palaeolithic (Micoquian/Mousterian), and to the final Palaeolithic (Magdalénien) of the Weichselian (Upper Pleistocene). Most lion bones from Balve Cave can be identified as early to middle Upper Pleistocene in age. From this cave, a relatively large amount of hyena remains, and many chewed, and punctured herbivorous and carnivorous bones, especially those of woolly rhinoceros, indicate periodic den use of Crocuta crocuta spelaea. In addition to those of the Balve Cave, nearly all lion remains in the Sauerland Karst caves were found in hyena den bone assemblages, except those described here material from the Keppler Cave cave bear den. Late Pleistocene spotted hyenas imported most probably Panthera leo spelaea body parts, or scavenged on lion carcasses in caves, a suggestion which is supported by comparisons with other cave sites in the Sauerland Karst. The complex taphonomic situation of lion remains in hyena den bone assemblages and cave bear dens seem to have resulted from antagonistic hyena-lion conflicts and cave bear hunting by lions in caves, in which all cases lions may sometimes have been killed and finally consumed by hyenas. -

Late Pleistocene Panthera Leo Spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) Skeletons

Late Pleistocene Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) skeletons from the Czech Republic (central Europe); their pathological cranial features and injuries resulting from intraspecific fights, conflicts with hyenas, and attacks on cave bears CAJUS G. DIEDRICH The world’s first mounted “skeletons” of the Late Pleistocene Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) from the Sloup Cave hyena and cave bear den in the Moravian Karst (Czech Republic, central Europe) are compilations that have used bones from several different individuals. These skeletons are described and compared with the most complete known skeleton in Europe from a single individual, a lioness skeleton from the hyena den site at the Srbsko Chlum-Komín Cave in the Bohemian Karst (Czech Republic). Pathological features such as rib fractures and brain-case damage in these specimens, and also in other skulls from the Zoolithen Cave (Germany) that were used for comparison, are indicative of intraspecific fights, fights with Ice Age spotted hyenas, and possibly also of fights with cave bears. In contrast, other skulls from the Perick and Zoolithen caves in Germany and the Urșilor Cave in Romania exhibit post mortem damage in the form of bites and fractures probably caused either by hyena scavenging or by lion cannibalism. In the Srbsko Chlum-Komín Cave a young and brain-damaged lioness appears to have died (or possibly been killed by hyenas) within the hyena prey-storage den. In the cave bear dominated bone-rich Sloup and Zoolithen caves of central Europe it appears that lions may have actively hunted cave bears, mainly during their hibernation. Bears may have occasionally injured or even killed predating lions, but in contrast to hyenas, the bears were herbivorous and so did not feed on the lion car- casses. -

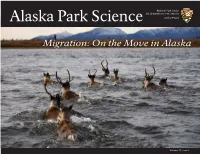

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

Research Article Extinctions of Late Ice Age Cave Bears As a Result of Climate/Habitat Change and Large Carnivore Lion/Hyena/Wolf Predation Stress in Europe

Hindawi Publishing Corporation ISRN Zoology Volume 2013, Article ID 138319, 25 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/138319 Research Article Extinctions of Late Ice Age Cave Bears as a Result of Climate/Habitat Change and Large Carnivore Lion/Hyena/Wolf Predation Stress in Europe Cajus G. Diedrich Paleologic, Private Research Institute, Petra Bezruce 96, CZ-26751 Zdice, Czech Republic Correspondence should be addressed to Cajus G. Diedrich; [email protected] Received 16 September 2012; Accepted 5 October 2012 Academic Editors: L. Kaczmarek and C.-F. Weng Copyright © 2013 Cajus G. Diedrich. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Predation onto cave bears (especially cubs) took place mainly by lion Panthera leo spelaea (Goldfuss),asnocturnalhuntersdeep in the dark caves in hibernation areas. Several cave bear vertebral columns in Sophie’s Cave have large carnivore bite damages. Different cave bear bones are chewed or punctured. Those lets reconstruct carcass decomposition and feeding technique caused only/mainlybyIceAgespottedhyenasCrocuta crocuta spelaea, which are the only of all three predators that crushed finally the long bones. Both large top predators left large tooth puncture marks on the inner side of cave bear vertebral columns, presumably a result of feeding first on their intestines/inner organs. Cave bear hibernation areas, also demonstrated in the Sophie’s Cave, were far from the cave entrances, carefully chosen for protection against the large predators. The predation stress must have increased on the last and larger cave bear populations of U. -

Captive Breeding of Mammals - Marco Masseti

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT – Vol. II – Captive Breeding of Mammals - Marco Masseti CAPTIVE BREEDING OF MAMMALS Marco Masseti Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Laboratori di Antropologia, Università di Firenze, Firenze, Italy Keywords: captive breeding, domestic mammals, threatened wild mammals, zoological gardens, arks, museums. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Captive breeding of mammals. The domestic species. 3. Selective breeding 4. Captive breeding of non-domestic species as a conservation strategy. 5. Captive breeding of threatened species 6. Captive breeding of threatened micromammals 7. Captive breeding and reintroduction of carnivores 8. Case studies 8.1 The Arabian Oryx Programme 8.2 The Case Of The Fallow Deer 9. Perspectives Bibliography Biographical Sketch 1. Introduction Mammals are currently among the main victims of human depredations on the environment. A huge amount of species and subspecies have disappeared to date, revealing human exploitation of natural resources as a long lasting process beginning in prehistorical periods and lasting until historical times. In the late Pleistocene, for example, the modern mammalian fauna assemblages of the Western Palaearctic Region were already defined. They would have yet comprised the totality of the species still surviving today, if some extinctions had not mainly affected large terrestrial mammals between 15.000UNESCO and 10.000 years BP, such –as the EOLSS mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach, 1803), the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus Rosenmuller & Heinroth, 1794), the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach, 1803), the giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus Berckhemer, 1910), and others. All these extinctions were without replacementSAMPLE by ecologically similar species:CHAPTERS for large mammals - i.e. species exceeding about 40 kg mean adult body weight - it has been estimated that Europe lost approximately 7 out of 24 genera (i.e. -

Frequency of Pathology in a Large Natural Sample from Natural Trap

Reumatismo, 2003; 55(1):58-65 RUBRICA DALLA RICERCA ALLA PRATICA Frequency of pathology in a large natural sample from Natural Trap Cave with special remarks on erosive disease in the Pleistocene La patologia osteoarticolare, con particolare riguardo a quella di tipo erosivo, nel Pleistocene: studio di un campione di reperti paleopatologici provenienti dalla Natural Trap Cave (Wyoming, USA) B.M. Rothschild1, L.D. Martin2 1The Arthritis Center of Northeast Ohio, University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and University of Akron; 2Museum of Natural History and Department of Systematics and Ecology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045 RIASSUNTO Nel presente studio vengono riportati i rilievi paleopatologici, con particolare riguardo alla presenza di artrite ero- siva, di osteoartrosi, di DISH , nonché ai segni di danno della dentizione, relativi ad un’ampia popolazione di mam- miferi, i cui resti (più di 30.000 ossa di 24 specie diverse) sono stati ritrovati nella Natural Trap Cave, Wyoming, USA. L’evidenza di artrite erosiva è confinata ai bovidi, Bison, Ovis e Bootherium, fatto osservabile anche in bisonti del tardo Pleistocene ritrovati nel Kansas (Twelve Mile Creek) e in un’altra località del Wisconsin, riferibile cronologi- camente al primo Olocene. Questi dati, ovvero la restrizione di tali segni di patologia articolare ad un singolo gene- re animale (Bovidi) e ad un determinato periodo storico, rende plausibile l’ipotesi che un agente patogeno, identifi- cabile col Mycobacterium tubercolosis, possa essere stato implicato nella genesi dell’artrite erosiva. Osteoartrosi e DISH sono risultate poco rappresentate nella popolazione animale della Natural Trap Cave, anche se il genere Bi- son ha dimostrato una discreta prevalenza di segni di osteoartrosi. -

Pleistocene Cave Hyenas in the Iberian Peninsula: New Insights from Los Aprendices Cave (Moncayo, Zaragoza)

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Pleistocene cave hyenas in the Iberian Peninsula: New insights from Los Aprendices cave (Moncayo, Zaragoza) Víctor Sauqué, Raquel Rabal-Garcés, Joan Madurell-Malaperia, Mario Gisbert, Samuel Zamora, Trinidad de Torres, José Eugenio Ortiz, and Gloria Cuenca-Bescós ABSTRACT A new Pleistocene paleontological site, Los Aprendices, located in the northwest- ern part of the Iberian Peninsula in the area of the Moncayo (Zaragoza) is presented. The layer with fossil remains has been dated by amino acid racemization to 143.8 ± 38.9 ka (earliest Late Pleistocene or latest Middle Pleistocene). Five mammal species have been identified in the assemblage: Crocuta spelaea (Goldfuss, 1823) Capra pyre- naica (Schinz, 1838), Lagomorpha indet, Arvicolidae indet and Galemys pyrenaicus (Geoffroy, 1811). The remains of C. spelaea represent a mostly complete skeleton in anatomical semi-connection. The hyena specimen represents the most complete skel- eton ever recovered in Iberia and one of the most complete remains in Europe. It has been compared anatomically and biometrically with both European cave hyenas and extant spotted hyenas. In addition, a taphonomic study has been carried out in order to understand the origin and preservation of these exceptional remains. The results sug- gest rapid burial with few scavenging modifications putatively produced by a medium sized carnivore. A review of the Pleistocene Iberian record of Crocuta spp. has been carried out, enabling us to establish one of the earliest records of C. spelaea in the recently discovered Los Aprendices cave, and also showing that the most extensive geographical distribution of this species occurred during the Late Pleistocene (MIS4- 2). -

Māhā'ulepū, Island of Kaua'i Reconnaissance Survey

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Pacific West Region, Honolulu Office February 2008 Māhā‘ulepū, Island of Kaua‘i Reconnaissance Survey THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………. 1 2 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY……………………………………………………..3 2.1 Background of the Study…………………………………………………………………..……… 3 2.2 Purpose and Scope of an NPS Reconnaissance Survey………………………………………4 2.2.1 Criterion 1: National Significance………………………………………………………..4 2.2.2 Criterion 2: Suitability…………………………………………………………………….. 4 2.2.3 Criterion 3: Feasibility……………………………………………………………………. 4 2.2.4 Criterion 4: Management Options………………………………………………………. 4 3 OVERVIEW OF THE STUDY AREA…………………………………………………. 5 3.1 Regional Context………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 3.2 Geography and Climate…………………………………………………………………………… 6 3.3 Land Use and Ownership………………………………………………………………….……… 8 3.4. Maps……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4 STUDY AREA RESOURCES………………………………………..………………. 11 4.1 Geological Resources……………………………………………………………………………. 11 4.2 Vegetation………………………….……………………………………………………...……… 16 4.2.1 Coastal Vegetation……………………………………………………………………… 16 4.2.2 Upper Elevation…………………………………………………………………………. 17 4.3 Terrestrial Wildlife………………..........…………………………………………………………. 19 4.3.1 Birds……………….………………………………………………………………………19 4.3.2 Terrestrial Invertebrates………………………………………………………………... 22 4.4 Marine Resources………………………………………………………………………...……… 23 4.4.1 Large Marine Vertebrates……………………………………………………………… 24 4.4.2 Fishes……………………………………………………………………………………..26