P020140409499958503920.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular and Functional Evolution of Hemoglobin in Perissodactyl

Molecular and functional evolution of hemoglobin in perissodactyl mammals (equids, tapirs, and rhinos) by Margaret Clapin A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Sciences University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada © 2019 Abstract: In this thesis, the oxygen binding characteristics of recombinant hemoglobin (Hb) isoforms (HbA [α2β2] and HbA2 [α2δ2]) from the extinct woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are compared with Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) and black rhino (Diceros bicornis) Hb. The major Hb component (HbA) of horses (Equus caballus) was also examined, as its blood O2 affinity has a low thermal sensitivity. This trait is commonly associated with cold-adaptation as it permits O2 to be offloaded at the cool peripheral tissues of regionally endothermic mammals, though the mechanism(s) by which the oxygenation enthalpy is reduced in horse Hb is unknown. It was hypothesized that the woolly rhino Hb isoforms would have similarly low thermal sensitivities to that of horses, either through enhanced effector binding or by altering the energetic transition from the tense to the relaxed state of hemoglobin. To test this hypothesis the hemoglobin coding sequences for each of the above species were determined and their Hb isoforms expressed using E. coli and purified. Oxygen equilibrium curves were then determined in the presence and absence of allosteric effectors at 25 and 37°C. Horse HbA had a low sensitivity to 2,3- diphosphoglycerate (DPG), though its low temperature sensitivity was primarily driven by increased DPG binding at the lower test temperature. -

Ancient Metaproteomics: a Novel Approach for Understanding Disease And

Ancient metaproteomics: a novel approach for understanding disease and diet in the archaeological record Jessica Hendy PhD University of York Archaeology August, 2015 ii Abstract Proteomics is increasingly being applied to archaeological samples following technological developments in mass spectrometry. This thesis explores how these developments may contribute to the characterisation of disease and diet in the archaeological record. This thesis has a three-fold aim; a) to evaluate the potential of shotgun proteomics as a method for characterising ancient disease, b) to develop the metaproteomic analysis of dental calculus as a tool for understanding both ancient oral health and patterns of individual food consumption and c) to apply these methodological developments to understanding individual lifeways of people enslaved during the 19th century transatlantic slave trade. This thesis demonstrates that ancient metaproteomics can be a powerful tool for identifying microorganisms in the archaeological record, characterising the functional profile of ancient proteomes and accessing individual patterns of food consumption with high taxonomic specificity. In particular, analysis of dental calculus may be an extremely valuable tool for understanding the aetiology of past oral diseases. Results of this study highlight the value of revisiting previous studies with more recent methodological approaches and demonstrate that biomolecular preservation can have a significant impact on the effectiveness of ancient proteins as an archaeological tool for this characterisation. Using the approaches developed in this study we have the opportunity to increase the visibility of past diseases and their aetiology, as well as develop a richer understanding of individual lifeways through the production of molecular life histories. iii iv List of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... -

Timeline of the Evolutionary History of Life

Timeline of the evolutionary history of life This timeline of the evolutionary history of life represents the current scientific theory Life timeline Ice Ages outlining the major events during the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes development of life on planet Earth. In P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs biology, evolution is any change across Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda successive generations in the heritable -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion characteristics of biological populations. o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ← Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity o Earliest animals ←Earliest plants at every level of biological organization, i Multicellular -1000 — c from kingdoms to species, and individual life ←Sexual reproduction organisms and molecules, such as DNA and – P proteins. The similarities between all present r -1500 — o day organisms indicate the presence of a t – e common ancestor from which all known r Eukaryotes o species, living and extinct, have diverged -2000 — z o through the process of evolution. More than i Huron ian – c 99 percent of all species, amounting to over ←Oxygen crisis [1] five billion species, that ever lived on -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Earth are estimated to be extinct.[2][3] Estimates on the number of Earth's current – Photosynthesis Pong ola species range from 10 million to 14 -3000 — A million,[4] of which about 1.2 million have r c been documented and over 86 percent have – h [5] e not yet been described. However, a May a -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen 2016 -

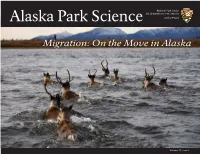

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-25 Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores Borkovic, Benjamin Borkovic, B. (2013). Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26635 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/498 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Investigating Sexual Dimorphism in Ceratopsid Horncores by Benjamin Borkovic A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2013 © Benjamin Borkovic 2013 Abstract Evidence for sexual dimorphism was investigated in the horncores of two ceratopsid dinosaurs, Triceratops and Centrosaurus apertus. A review of studies of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate fossil record revealed methods that were selected for use in ceratopsids. Mountain goats, bison, and pronghorn were selected as exemplar taxa for a proof of principle study that tested the selected methods, and informed and guided the investigation of sexual dimorphism in dinosaurs. Skulls of these exemplar taxa were measured in museum collections, and methods of analysing morphological variation were tested for their ability to demonstrate sexual dimorphism in their horns and horncores. -

Captive Breeding of Mammals - Marco Masseti

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT – Vol. II – Captive Breeding of Mammals - Marco Masseti CAPTIVE BREEDING OF MAMMALS Marco Masseti Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Laboratori di Antropologia, Università di Firenze, Firenze, Italy Keywords: captive breeding, domestic mammals, threatened wild mammals, zoological gardens, arks, museums. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Captive breeding of mammals. The domestic species. 3. Selective breeding 4. Captive breeding of non-domestic species as a conservation strategy. 5. Captive breeding of threatened species 6. Captive breeding of threatened micromammals 7. Captive breeding and reintroduction of carnivores 8. Case studies 8.1 The Arabian Oryx Programme 8.2 The Case Of The Fallow Deer 9. Perspectives Bibliography Biographical Sketch 1. Introduction Mammals are currently among the main victims of human depredations on the environment. A huge amount of species and subspecies have disappeared to date, revealing human exploitation of natural resources as a long lasting process beginning in prehistorical periods and lasting until historical times. In the late Pleistocene, for example, the modern mammalian fauna assemblages of the Western Palaearctic Region were already defined. They would have yet comprised the totality of the species still surviving today, if some extinctions had not mainly affected large terrestrial mammals between 15.000UNESCO and 10.000 years BP, such –as the EOLSS mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach, 1803), the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus Rosenmuller & Heinroth, 1794), the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach, 1803), the giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus Berckhemer, 1910), and others. All these extinctions were without replacementSAMPLE by ecologically similar species:CHAPTERS for large mammals - i.e. species exceeding about 40 kg mean adult body weight - it has been estimated that Europe lost approximately 7 out of 24 genera (i.e. -

The Rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and Their Nutrition

During the Pleistocene, there were three main groups of Im Pleistozän traten drei Hauptgruppen von Nashörnern auf, rhinoceroses, each of them in a different part of the Old jede in einem anderen Teil der Alten Welt: die afrikanische World: the African lineage leads to the modern square- Linie führt zu den heutigen Breitmaul- und Spitzmaulnashör- lipped rhinoceros and black rhinoceros, the Asian group nern, die asiatische Gruppe umfasst das Panzer-, das Suma- includes the great one-horned rhinoceros, the Sumatra tra- und das Javanashorn sowie ihre Vorfahren. Zur dritten rhinoceros and the Java rhinoceros as well as their ances- Gruppe, die im späten Pleistozän ausstarb, gehören Coelo- tors. The third group, which became extinct in the Late donta und Stephanorhinus. Das Wollhaarnashorn (Coelodonta Pleistocene, includes Coelodonta and Stephanorhinus. The antiquitatis) trat in Europa zum ersten Mal während der woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) appeared in Elsterkaltzeit auf. Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis, das Wald- Europe for the first time during the Elsterian cold period. nashorn, ist auf die Interglaziale beschränkt und wanderte Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis, the forest rhinoceros, is lim- wahrscheinlich nach jeder Kaltzeit erneut von Asien aus ein. ited to the interglacial periods and probably dispersed again Das Steppennashorn (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus) ist wie- and again after each cold period from Asia into Europe. The derum in Europa seit 450 000 Jahren heimisch. In Neumark- steppe rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus) again has Nord konnten diese drei Nashörner zusammen nachgewiesen been present in Europe for 450,000 years. All three types werden, was umso bemerkenswerter ist, weil das Wollhaar- of rhinoceros together could be documented in Neumark- nashorn im Allgemeinen als Vertreter der Glazialfaunen gilt. -

Genetics and the Last Stand of the Sumatran Rhinoceros Dicerorhinus Sumatrensis

Genetics and the last stand of the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis B ENOÎT G OOSSENS,MILENA S ALGADO-LYNN,JEFFRINE J. ROVIE-RYAN A BDUL H. AHMAD,JUNAIDI P AYNE,ZAINAL Z. ZAINUDDIN S ENTHILVEL K. S. S. NATHAN and L AURENTIUS N. AMBU Abstract The Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus rhinoceros Rhinoceros sondaicus in Vietnam (Brook et al., sumatrensis is on the brink of extinction. Although habitat 2011), are we to witness the loss of another rhinoceros loss and poaching were the reasons of the decline, today’s species? Genetic studies have played an important role in reproductive isolation is the main threat to the survival of identifying conservation priorities (Moritz, 1994, 2002;De the species. Genetic studies have played an important role Salle & Amato, 2004; Caballero et al., 2009; Frankham, 2009; in identifying conservation priorities, including for rhino- Laikre, 2010), including for species of rhinoceros (Ashley ceroses. However, for a species such as the Sumatran et al., 1990; Dinerstein & McCracken, 1990; Amato et al., rhinoceros, where time is of the essence in preventing 1995; Morales et al., 1997; Harley et al., 2005; Fernando et al., extinction, to what extent should genetic and geographical 2006; Scott, 2008; Kim, 2009; Willerslev et al., 2009). distances be taken into account in deciding the most However, for a species such as the Sumatran rhinoceros, urgently needed conservation interventions? We propose where time is of the essence in preventing extinction, to that the populations of Sumatra and Borneo be considered what extent should genetic and geographical distances be as a single management unit. taken into account in deciding the most urgently needed human interventions? Keywords Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, extinction, genetics, Since its appearance in the Eocene, the family genome resource banking, Sumatran rhinoceros, threatened Rhinocerotidae has comprised . -

Cave Bear, Cave Lion and Cave Hyena Skulls from The

COBISS: 1.01 CAVE BEAR, CAVE LION AND CAVE HYENA SKULLS FROM THE PUBLIC COLLECTION AT THE HUMBOLDT MUSEUM IN BERLIN Lobanje jamskega medveda, jamskega leva in jamske hijene iz zbirke Humboldtovega muzeja V Berlinu Stephan KEMPE1 & Doris DÖPPES2 Abstract UDC 569(069.5)(430 Berlin) Izvleček UDK 569(069.5)(430 Berlin) 069.02:569(430 Berlin) 069.02:569(430 Berlin) Stephan Kempe and Doris Döppes: Cave bear, cave lion and Stephan Kempe and Doris Döppes: Lobanje jamskega medve- cave hyena skulls from the public collection at the Humboldt da, jamskega leva in jamske hijene iz zbirke Humboldtovega Museum in Berlin muzeja v Berlinu The Linnean binomial system rests on the description of a ho- Linnejev binomski sistem poimenovanja temelji na opisu ho- lotype. The first fossil vertebrate species named accordingly was lotipa. Jamski medved je bil prva vrsta fosilnih vretenčarjev za- Ursus spelaeus, the cave bear. It was described by Rosenmüller pisana v tem sistemu. V svoji disertaciji ga je opisal Rosenmül- in 1794 in his dissertation using a skull from the Zoolithen Cave ler leta 1794, pri čemer je uporabil okostje iz jame Zoolithen (Gailenreuth Cave) in Frankonia, Germany. The whereabouts of (Gailenreuthska jama) v Frankoniji. Okoliščine oziroma usoda this skull is unknown. In the Humboldt Museum, Berlin, histor- tega skeleta je neznana. Humboldtov muzej v Berlinu hrani tri ic skulls of the three “spelaeus species” (cave bear, cave lion, cave fosilne vrste jamskih vretenčarjev: jamskega medveda, hijeno in hyena) are displayed. We were allowed to investigate them and jamskega leva. Omogočeno nam je bilo raziskovanje teh okostij further material in the Museum’s archive in an attempt to locate in ostalega arhivskega gradiva, pri čemer je bil naš namen od- the holotype skull. -

Woolly Rhinoceros Fossil Jaw

Museum objects are irreplaceable evidence of our history and heritage and can really bring your lessons to life. Each of these downloadable resources explores one of the objects in our collection. For even more ideas, discover our loan boxes at http://schoolloans.readingmuseum.org.uk/ and search our amazing online database at http://collections.readingmuseum.org.uk/ Woolly Rhinoceros fossil jaw Follow this link to online database to see the object’s full record Object: Woolly rhino jaw fragments Museum object number: REDMG: 1997.15.1 Material: Fossil jaw (bone and teeth) Size: 220 mm wide and 160mm wide Date: circa 26,000 BCE The woolly rhinoceros had a thick fur coat and lived in Europe during the Last Ice Age. They could reach 2 metres in height, five metres in length and weigh 3.5 tonnes. These fossilised pieces of the woolly rhino’s jaws, found in Pleistocene cave deposits at Kent's Cavern (Torquay), show the big and powerful teeth of these prehistoric animals. Woolly rhinos (Coelodonta antiquitatis) are an extinct rhino species that lived in open grassland and tundra. The woolly rhinoceros was related to the modern rhino. Some woolly rhino species (nick-named unicorns) had one horn, but these jaws belonged to a species with two horns. Rhino’s horn is made from keratin (the protein in hair and fingernails). The front horn was large, curved and could also be used in fights with other animals. Rhinos held their heads low to the ground and used their horns to push snow aside. They were herbivores, the high-crowned molars, the largest teeth were adapted to chewing the tough steppe grasses that were spread across Ice Age Europe. -

Coelodonta Antiquitatis) from Whitemoor Haye Quarry, Staffordshire (UK): Palaeoenvironmental Context and Significance

JOURNAL OF QUATERNARY SCIENCE (2013) 28(2) 118–130 ISSN 0267-8179. DOI: 10.1002/jqs.2594 A Middle Devensian woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) from Whitemoor Haye Quarry, Staffordshire (UK): palaeoenvironmental context and significance DANIELLE SCHREVE,1* ANDY HOWARD,2 ANDREW CURRANT,3 STEPHEN BROOKS,4 SIMON BUTEUX,2 RUSSELL COOPE,1,5 BARNABY CROCKER,1 MICHAEL FIELD,6 MALCOLM GREENWOOD,7 JAMES GREIG2 and PHILLIP TOMS8 1Department of Geography, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK 2Institute of Archaeology & Antiquity, University of Birmingham, UK 3Department of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, London, UK 4Department of Entomology, Natural History Museum, London, UK 5School of Geography Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK 6Faculty of Archeology, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands 7Department of Geography, Loughborough University, UK 8School of Natural and Social Sciences, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham, UK Received 21 March 2012; Revised 14 September 2012; Accepted 16 September 2012 ABSTRACT: This paper reports the discovery of a rare partial skeleton of a woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach, 1799) and associated fauna from a low Pleistocene terrace of the River Tame at Whitemoor Haye, Staffordshire, UK. A study of the sedimentary deposits around the rhino skeleton and associated organic-rich clasts containing pollen, plant and arthropod remains suggests that the animal was rapidly buried on a braided river floodplain surrounded by a predominantly treeless, herb-rich grassland. Highlights of the study include the oldest British chironomid record published to date and novel analysis of the palaeoflow regime using caddisfly remains. For the first time, comparative calculations of coleopteran and chironomid palaeotemperatures have been made on the same samples, suggesting a mean July temperature of 8–11 8C and a mean December temperature of between À22 and À16 8C. -

Arctic Biodiversity Assessment

566 Arctic Biodiversity Assessment The lesser snow goose Chen c. caerulescens shows an approximate east-west cline in their Nearctic breeding distribution in frequency of pale or dark morphs, with blue morphs most common in the east. Although studies of fitness components failed to uncover any adaptive advantage associated with either morph, geese show strong mating preference based on the color of their parents, leading to assortative mating. Queen Maud Gulf Bird Sanctuary, Nunavut, Canada. Photo: Gustaf Samelius. 567 Chapter 17 Genetics Lead Author Joseph A. Cook Contributing Authors Christian Brochmann, Sandra L. Talbot, Vadim B. Fedorov, Eric B. Taylor, Risto Väinölä, Eric P. Hoberg, Marina Kholodova, Kristinn P. Magnusson and Tero Mustonen Contents Summary ..............................................................568 17.5. Recommendations and conservation measures ������������������582 17.1. Introduction .....................................................568 17.5.1. Call for immediate development of freely available, specimen-based archives ...................................582 17.2. Systematics, phylogenetics and phylogeography ................569 17.5.1.1. Build European, Asian and North American 17.2.1. Systematics ................................................569 tissue archives .....................................582 17.2.1.1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy �����������������������569 17.5.2. Expand biodiversity informatics ............................582 17.2.1.2. Systematics and phylogenetics in Arctic species ....569 17.5.2.1. Connect GenBank, EMBL and DDJB to Archives .....582 17.2.2. Phylogeography – setting the stage for interpreting 17.5.2.2. Connect GenBank (Genomics) to GIS applications ..583 changing environmental conditions ........................571 17.5.2.3. Stimulate emerging pathogen investigations 17.2.2.1. Influence of dynamic climates on structuring through integrated inventories ���������������������583 Arctic diversity .....................................571 17.5.2.4. Develop educational interfaces and portals for 17.2.2.2.