Thomas E. Ricks Unless We Can Return a Little More to First Principles, & Act a Little Th November 24 , 2020 More Upon Patriotic Ground, I Do Not Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Principles of Polite Learning Are Laid Down in a Way Most Suitable for Trying the Genius, and Advancing the Instruc�On of Youth

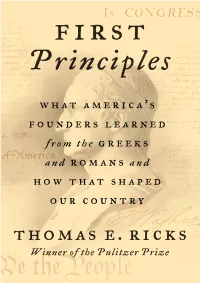

Dedicaon For the dissenters, who conceived this naon, and improve it sll Epigraph Unless we can return a lile more to first principles, & act a lile more upon patrioc ground, I do not know . what may be the issue of the contest. —George Washington to James Warren, March 31, 1779 Contents Cover Title Page Dedicaon Epigraph A Note on Language Chronology Map Prologue Part I: Acquision Chapter 1: The Power of Colonial Classicism Chapter 2: Washington Studies How to Rise in Colonial Society Chapter 3: John Adams Aims to Become an American Cicero Chapter 4: Jefferson Blooms at William & Mary Chapter 5: Madison Breaks Away to Princeton Part II: Applicaon Chapter 6: Adams and the Fuse of Rebellion Chapter 7: Jefferson’s Declaraon of the “American Mind” Chapter 8: Washington Chapter 9: The War Strains the Classical Model Chapter 10: From a Difficult War to an Uneasy Peace Chapter 11: Madison and the Constuon Part III: Americanizaon Chapter 12: The Classical Vision Smashes into American Reality Chapter 13: The Revoluon of 1800 Chapter 14: The End of American Classicism Epilogue Acknowledgments Appendix: The Declaraon of Independence Notes Index About the Author Also by Thomas E. Ricks Copyright About the Publisher A Note on Language I have quoted the words of the Revoluonary generaon as faithfully as possible, including their unusual spellings and surprising capitalizaons. I did this because I think it puts us nearer their world, and also out of respect: I wouldn’t change their words when quong them, so why change their spellings? For some reason, I am fond of George Washington’s apoplecc denunciaon of an “ananominous” leer wrien by a munous officer during the Revoluonary War. -

Classical Rhetoric in America During the Colonial and Early National Periods

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Communication Scholarship Communication 9-2011 “Above all Greek, above all Roman Fame”: Classical Rhetoric in America during the Colonial and Early National Periods James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/comm_facpub Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Cultural History Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation James M. Farrell, "'Above all Greek, above all Roman fame': Classical Rhetoric in America during the Colonial and Early National Periods," International Journal of the Classical Tradition 18:3, 415-436. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Above all Greek, above all Roman Fame”: Classical Rhetoric in America during the Colonial and Early National Periods James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire The broad and profound influence of classical rhetoric in early America can be observed in both the academic study of that ancient discipline, and in the practical approaches to persuasion adopted by orators and writers in the colonial period, and during the early republic. Classical theoretical treatises on rhetoric enjoyed wide authority both in college curricula and in popular treatments of the art. Classical orators were imitated as models of republican virtue and oratorical style. Indeed, virtually every dimension of the political life of early America bears the imprint of a classical conception of public discourse. -

First Principles Foundational Concepts to Guide Politics and Policy

FIRST PRINCIPLES FOUNDATIONAL CONCEPTS TO GUIDE POLITICS AND POLICY NO. 70 | SEptEMBER 30, 2018 The Rise and Fall of Political Parties in America Joseph Postell Abstract Political parties are not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. Nevertheless, America’s founders understood that the republic they were founding requires parties as a means for keeping government accountable to the people. Throughout America’s history, the power of political parties has risen and fallen, reaching their nadir in the last few decades. Americans today attribute to parties the very maladies from which great parties would save us if only we would restore them. Great political parties of the past put party principles above candidate personalities and institutionalized resources to maintain coalitions based on principle. They moderated politics and provided opportunities for leadership in Congress instead of shifting all power to the executive, enabling the republic to en- joy the benefits of checks and balances while avoiding excessive gridlock. Parties also encouraged elected officials to put the national interest ahead of narrow special interests. f there is one thing about politics that unites perceived as “the establishment.” Americans are IAmericans these days, it is their contempt for bipartisan in their condemnation of partisanship. political parties and partisanship. More Americans Americans have always viewed political parties with today identify as independents than with either of skepticism. The Constitution does not mention parties the two major political parties. Citizens boast that and did not seem to anticipate their emergence. In spite of they “vote for the person, not for the party,” and this, however, parties play an essential role in our repub- denounce fellow citizens or representatives who lican form of government and have done so throughout blindly toe the party line. -

Of First Principles & Organic Laws

Dominican Scholar Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects Student Scholarship 5-2017 Of First Principles & Organic Laws Pietro Poggi Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2017.hum.05 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Poggi, Pietro, "Of First Principles & Organic Laws" (2017). Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects. 299. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2017.hum.05 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Master's Theses, Capstones, and Culminating Projects by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of First Principles & Organic Laws A culminating project submitted to the faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Humanities by Piêtro G. Pôggi San Rafael, California May, 2017 This Thesis—written under the direction of the candidate’s Thesis Advisor and approved by the Graduate Humanities Program Director—has been presented to, and accepted by, the Department of the Graduate Humanities, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Humanities. The content and research methodologies presented in this work represent the work of the candidate alone. Piêtro G. Pôggi 17 May, 2017 Master of Arts in Humanities Candidate Joan Baranow. Ph.D. 17 May, 2017 Director of Graduate Humanities Jordan Lieser, Ph.D. 07 May, 2017 Assistant Professor of History/Thesis Advisor Gigi Gokcek, Ph.D. -

FIRST PRINCIPLES What America’S Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country by Thomas E

HARPER NEWS “[Thomas Ricks] has strong opinions he does not try to hide [and] a deep wellspring of knowledge about both military policy and military history.” — The New York Times Book Review FIRST PRINCIPLES What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country By Thomas E. Ricks “Ricks does something quite remarkable: he takes a seemingly academic topic—the Greco- Roman education of the Founding Fathers—and makes it resonate with grand relevance… Offering a look at the Founders rarely glimpsed, Ricks successfully argues that America needs to rediscover its classical roots.”—Library Journal, STARRED REVIEW “An immersive and enlightening look at how the classical educations of the first four U.S. presidents (George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison) influenced their thinking and the shape of American democracy… With incisive selections from primary sources and astute cultural and political analysis, this lucid and entertaining account is a valuable take on American history.” —Publishers Weekly, STARRED REVIEW “An exploration of the major influences of America’s first four presidents…[In 2016 Ricks asked,] ‘What kind of nation do we now have? Is this what was designed or intended by the nation’s founders?’…[He] reassures readers that the durable Constitutional order can handle a Donald Trump, and he concludes with 10 strategies for putting the nation back on course…Penetrating history with a modest dollop of optimism.”—Kirkus Reviews In FIRST PRINCIPLES: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country (Harper; November 10, 2020; NetGalley; Edelweiss), Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and #1 New York Times bestselling author Thomas E. -

Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding Jud Campbell University of Richmond, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2017 Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding Jud Campbell University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Jud Campbell, Republicanism and Natural Rights at the Founding, 32 Const. Comment 85 (2017) This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 5 - CAMPBELL_DRAFT 1.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/3/17 8:59 AM REPUBLICANISM AND NATURAL RIGHTS AT THE FOUNDING OUR REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTION: SECURING THE LIBERTY AND SOVEREIGNTY OF WE THE PEOPLE. By Randy E. Barnett.1 New York: HarperCollins Publishers. 2016. Pp. xiv + 283. $26.99 (cloth). Jud Campbell2 Americans mostly take constitutional legitimacy for granted, leaving the Supreme Court and its illustrious bar to do their work without concern for political philosophy. A great strength of Randy Barnett’s scholarship, including his latest book, Our Republican Constitution,3 is his sustained effort to dislodge that philosophical complacency. Barnett calls on us to consider why our Constitution is legitimate before we decide how it should be interpreted. In this sense, Barnett brings us closer to an eighteenth- century intellectual world commonly known as “the Founding.” Constitutionalism at the Founding was intimately tied to questions of political philosophy, based in part on the idea of “natural rights.” Constitutional historians have disparaged the importance of natural rights,4 but Barnett deserves credit for 1. -

First Principles Foundational Concepts to Guide Politics and Policy

FIRST PRINCIPLES FOUNDATIONAL CONCEPTS TO GUIDE POLITICS AND POLICY NO. 64 | October 5, 2017 Can the State Be Neutral on Marriage? Scott Yenor, PhD Abstract Successful efforts to extend marriage recognition to same-sex couples have tempted some dispirited well-wishers of traditional marriage, among others, to call for the “privatization of marriage” by getting the state to adopt a neutral stance toward it. Such a policy would require the government to refrain from promoting and supporting marriage and parenthood, effectively making them merely private choices. This misguided approach subordi- nates considerations of how best to form self-governing citizens to the new ethic of self-expression, imagining that a responsible citizenry will spontaneously emerge. It also produces a culture increasingly hostile to marriage, ignores the problems posed by the human passions, and indirectly opens the door to intrusive state involvement. By contrast, government support for marriage as traditionally understood nurtures the best possible conditions for human flourishing. ome people argue that the government should essentially private. People experience much of it Srefrain as much as possible from making assump- behind closed doors and beyond the legitimate scope tions about the goals, form, and internal workings of of government. People do not love, marry, or have marriage and about the desirability of entering into children pursuant to government directives. Cou- marriage and staying married. Both liberals and lib- ples arrange most of their common life without state ertarians emphasize the importance of state neu- intervention, and parents have enormous discretion trality as a means of securing individual autonomy as to how they educate their children. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 16-1436 & No. 16-1540 In the Supreme Court of the United States DONALD J. TRUMP, et al., PETITIONERS, v. INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT, et al., RESPONDENTS. DONALD J. TRUMP, et al., PETITIONERS, v. STATE OF HAWAII, et al., RESPONDENTS. ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH AND NINTH CIRCUITS BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW SCHOLARS IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ALEXANDRA M. WALSH MICHAEL J. ZYDNEY KIERAN GOSTIN MANNHEIMER ROXANA C. GUIDERO Professor of Law WILKINSON WALSH + Salmon P. Chase College of Law ESKOVITZ LLP Northern Kentucky University 2001 M Street NW 518 Nunn Hall 10th Floor Highland Heights, KY 41099 Washington, DC 20036 (859) 572-5862 (202) 847-4000 [email protected] [email protected] ILYA SOMIN Counsel of Record Professor of Law George Mason University 3301 Fairfax Dr. Arlington, VA 22201 (703) 993-8069 [email protected] I QUESTION PRESENTED Amici will address the following issue only: 1. Whether Sections 2(c), 6(a), and 6(b) of Executive Order No. 13,780 violate the Establishment Clause. II TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) QUESTION PRESENTED ........................................ I INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................. 3 I. THE BILL OF RIGHTS LIMITS FEDERAL POWER OVER IMMIGRATION ..................... 3 A. The Bill of Rights Consists Largely of Structural Constraints that Limit the Power of the Federal Government in Every Realm, Including Immigration ......... 3 1. The Text of the First Amendment Does Not Limit Its Applicability Based on Either Territory or Citizenship ......... 3 2. The Original Understanding of the Bill of Rights Does Not Set Territorial or Citizenship Status Limitations on Its Applicability........................................ -

Cato: a Tragedy and Selected Essays 00-L2990-FM 9/16/04 7:16 AM Page Ii

00-L2990-FM 9/16/04 7:16 AM Page i Cato: A Tragedy and selected essays 00-L2990-FM 9/16/04 7:16 AM Page ii Joseph Addison 00-L2990-FM 9/16/04 7:16 AM Page iii Cato: A Tragedy and selected essays Joseph Addison Edited by Christine Dunn Henderson and Mark E. Yellin With a Foreword by Forrest McDonald liberty fund Indianapolis 00-L2990-FM 9/16/04 7:16 AM Page iv This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encour- age study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. © 2004 by Liberty Fund All rights reserved Frontispiece, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Bt (1646 –1723), is from the National Portrait Gallery, London. The engraving on page 2 is reproduced by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library. “The Life and Character of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis” is reproduced by cour- tesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. Printed in the United States of America 08 07 06 05 04 c 54321 08 07 06 05 04 p 54321 Liberty of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Addison, Joseph, 1672–1719. Cato: a tragedy, and selected essays / edited by Christine Dunn Henderson and Mark E. Yellin; with a foreword by Forrest McDonald. -

Broadwater on Ricks, 'First Principles: What America's Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country'

H-Early-America Broadwater on Ricks, 'First Principles: What America's Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country' Review published on Tuesday, August 3, 2021 Thomas E. Ricks. First Principles: What America's Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country. New York: Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2020. xxiv + 386 pp. $22.49 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-06-299745-6. Reviewed by Jeff Broadwater (Barton College)Published on H-Early-America (August, 2021) Commissioned by Troy Bickham (Texas A&M University) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56305 In First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country, Thomas E. Ricks explores the impact of classicism on George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison and how, through them, it affected the new American nation. Ricks divides his fourteen chapters into three parts. The first, “Acquisition,” focuses on his four founders’ formative years. The next, “Application,” examines their careers during the American Revolution and its immediate aftermath. The last, “Americanization,” describes the demise of classical ideals amid the political turmoil of the early republic. Ricks argues that, contrary to modern tastes, the revolutionary generation generally preferred the lessons of Roman history to the wisdom of Greece. “The dominant political narrative of colonial American elites,” he writes, “was the story of how the Roman orator Cicero put down the Catiline conspiracy to take over Rome” (p. 41). In Ricks’s mind, however, classical republicanism “steered the founders wrong on three crucial issues:” their reliance on public virtue to maintain a republican government, their opposition to political parties, and their tolerance of slavery (pp. -

America's Founders and the Principles of Foreign Policy

No. 33 America’s Founders and the Principles of Foreign Policy: Sovereign Independence, National Interests, and the Cause of Liberty in the World Matthew Spalding, Ph.D. Abstract: America’s Founders sought to define a national good that transcended local interests and prejudices. The national good included the common benefits of self-defense and prosperity that all Ameri- cans would realize by participating in a large, commercial nation able to hold its own in an often hostile world. But it was only with the constitutional rule of law that the higher purpose, or true national interest, of America could be realized. That purpose was to demonstrate to all mankind the feasibility of self-government and the suitability of justice as the proper and sustainable ground for relations among nations and peoples. The honor of striving for domestic and international justice would give moral purpose to the American character. The United States would support, defend, and advance the cause of freedom everywhere. It would be a refuge for the sober, industrious, and virtuous of the world, as well as for victims of persecution. By sympathy and appropriate action, Americans would show themselves to be true friends of humanity. ndependence was the clarion call of the American so they also were declaring their unity—or interde- IRevolution. While we tend to think of independence pendence—as a people, a compact of states, and a new mainly as an important historic event that marks our nation. Independence implied at the same time separa- separation from Great Britain, the Founders and sub- tion as well as the creation of a new and independent sequent generations had a larger understanding of country, living and governing by its own means and what was signified by the national independence they according to its own ways. -

The Central Meaning of Republican Government: Popular Sovereignty, Majority Rule, and the Denominator Problem

THE CENTRAL MEANING OF REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT: POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY, MAJORITY RULE, AND THE DENOMINATOR PROBLEM AKHIL REED AMAR* Like the apostle Paul, Republican Government has been "made all things to all men."1 The concept is indeed a spacious one, and many particular ideas can comfortably nestle under its big tent. Surprisingly, however, few modern scholars seem even aware of the central meaning of Republican Government--of the main pole that keeps the big top up, as it were. Today, I shall describe this central pillar as understood and acted upon in the Founding, Antebellum, and Civil War eras. The central pillar of Republican Government, I claim, is popular sovereignty. In a Republican Government, the people rule. They do not necessarily rule directly, day-to-day. Republican Government probably does not (as some have claimed) prohibit all forms of direct democracy, such as initiative and referendum,2 but neither does it require ordinary lawmaking via these direct populist mechanisms. What it does require is that the structure of day-to-day govern ment--the Constitution--be derived from "the People" and be legally alterable by a "majority" ofthem. These corollanes of popular sover eignty--the people's right to alter or abolish, and popular majority rule in making and changing constitutions--were bedrock principles in the Founding, Antebellum, and Civil War eras.3 And I shall show that these principles were understood and accepted as the central * Southmayd Professor, Yale Law School. This symposium essay builds on my Southmayd Inaugural Lecture. See Akhil Reed Amar, The Consent of the Governed: Constitutional Amendment Outside Article V, 94 COLUM.