First Principles Foundational Concepts to Guide Politics and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

20 Thomas Jefferson.Pdf

d WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE THINK ABOUT THOMAS JEFFERSON Todd Estes Thomas Jefferson is America’s most protean historical figure. His meaning is ever-changing and ever-changeable. And in the years since his death in 1826, his symbolic legacy has varied greatly. Because he was literally present at the creation of the Declaration of Independence that is forever linked with him, so many elements of subsequent American life—good and bad—have always attached to Jefferson as well. For a quarter of a century—as an undergraduate, then a graduate student, and now as a professor of early American his- tory—I have grappled with understanding Jefferson. If I have a pretty good handle on the other prominent founders and can grasp the essence of Washington, Madison, Hamilton, Adams and others (even the famously opaque Franklin), I have never been able to say the same of Jefferson. But at least I am in good company. Jefferson biographer Merrill Peterson, who spent a scholarly lifetime devoted to studying him, noted that of his contemporaries Jefferson was “the hardest to sound to the depths of being,” and conceded, famously, “It is a mortifying confession but he remains for me, finally, an impenetrable man.” This in the preface to a thousand page biography! Pe- terson’s successor as Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor at Mr. Jefferson’s University of Virginia, Peter S. Onuf, has noted the difficulty of knowing how to think about Jefferson 21 once we sift through the reams of evidence and confesses “as I always do when pressed, that I am ‘deeply conflicted.’”1 The more I read, learn, write, and teach about Jefferson, the more puzzled and conflicted I remain, too. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling James Carpenter (Binghamton University) Abstract I challenge the traditional argument that Jefferson’s educational plans for Virginia were built on mod- ern democratic understandings. While containing some democratic features, especially for the founding decades, Jefferson’s concern was narrowly political, designed to ensure the survival of the new republic. The significance of this piece is to add to the more accurate portrayal of Jefferson’s impact on American institutions. Submit your own response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal.org/home Read responses to this article online http://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol21/iss2/5 ew historical figures have undergone as much advocate of public education in the early United States” (p. 280). scrutiny in the last two decades as has Thomas Heslep (1969) has suggested that Jefferson provided “a general Jefferson. His relationship with Sally Hemings, his statement on education in republican, or democratic society” views on Native Americans, his expansionist ideology and his (p. 113), without distinguishing between the two. Others have opted suppressionF of individual liberties are just some of the areas of specifically to connect his ideas to being democratic. Williams Jefferson’s life and thinking that historians and others have reexam- (1967) argued that Jefferson’s impact on our schools is pronounced ined (Finkelman, 1995; Gordon- Reed, 1997; Kaplan, 1998). because “democracy and education are interdependent” and But his views on education have been unchallenged. While his therefore with “education being necessary to its [democracy’s] reputation as a founding father of the American republic has been success, a successful democracy must provide it” (p. -

The Causes of the American Revolution

Page 50 Chapter 12 By What Right Thomas Hobbes John Locke n their struggle for freedom, the colonists raised some age-old questions: By what right does government rule? When may men break the law? I "Obedience to government," a Tory minister told his congregation, "is every man's duty." But the Reverend Jonathan Boucher was forced to preach his sermon with loaded pistols lying across his pulpit, and he fled to England in September 1775. Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that when people are governed "under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such a Government." Both Boucher and Jefferson spoke to the question of whether citizens owe obedience to government. In an age when kings held near absolute power, people were told that their kings ruled by divine right. Disobedience to the king was therefore disobedience to God. During the seventeenth century, however, the English beheaded one King (King Charles I in 1649) and drove another (King James II in 1688) out of England. Philosophers quickly developed theories of government other than the divine right of kings to justify these actions. In order to understand the sources of society's authority, philosophers tried to imagine what people were like before they were restrained by government, rules, or law. This theoretical condition was called the state of nature. In his portrait of the natural state, Jonathan Boucher adopted the opinions of a well- known English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes believed that humankind was basically evil and that the state of nature was therefore one of perpetual war and conflict. -

First Principles of Polite Learning Are Laid Down in a Way Most Suitable for Trying the Genius, and Advancing the Instruc�On of Youth

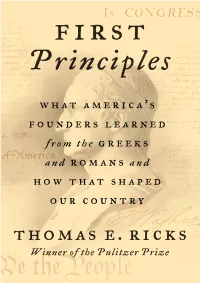

Dedicaon For the dissenters, who conceived this naon, and improve it sll Epigraph Unless we can return a lile more to first principles, & act a lile more upon patrioc ground, I do not know . what may be the issue of the contest. —George Washington to James Warren, March 31, 1779 Contents Cover Title Page Dedicaon Epigraph A Note on Language Chronology Map Prologue Part I: Acquision Chapter 1: The Power of Colonial Classicism Chapter 2: Washington Studies How to Rise in Colonial Society Chapter 3: John Adams Aims to Become an American Cicero Chapter 4: Jefferson Blooms at William & Mary Chapter 5: Madison Breaks Away to Princeton Part II: Applicaon Chapter 6: Adams and the Fuse of Rebellion Chapter 7: Jefferson’s Declaraon of the “American Mind” Chapter 8: Washington Chapter 9: The War Strains the Classical Model Chapter 10: From a Difficult War to an Uneasy Peace Chapter 11: Madison and the Constuon Part III: Americanizaon Chapter 12: The Classical Vision Smashes into American Reality Chapter 13: The Revoluon of 1800 Chapter 14: The End of American Classicism Epilogue Acknowledgments Appendix: The Declaraon of Independence Notes Index About the Author Also by Thomas E. Ricks Copyright About the Publisher A Note on Language I have quoted the words of the Revoluonary generaon as faithfully as possible, including their unusual spellings and surprising capitalizaons. I did this because I think it puts us nearer their world, and also out of respect: I wouldn’t change their words when quong them, so why change their spellings? For some reason, I am fond of George Washington’s apoplecc denunciaon of an “ananominous” leer wrien by a munous officer during the Revoluonary War. -

Life, Liberty, and . . .: Jefferson on Property Rights

Journal of Libertarian Studies Volume 18, no. 1 (Winter 2004), pp. 31–87 2004 Ludwig von Mises Institute www.mises.org LIFE, LIBERTY, AND . : JEFFERSON ON PROPERTY RIGHTS Luigi Marco Bassani* Property does not exist because there are laws, but laws exist because there is property.1 Surveys of libertarian-leaning individuals in America show that the intellectual champions they venerate the most are Thomas Jeffer- son and Ayn Rand.2 The author of the Declaration of Independence is an inspiring source for individuals longing for liberty all around the world, since he was a devotee of individual rights, freedom of choice, limited government, and, above all, the natural origin, and thus the inalienable character, of a personal right to property. However, such libertarian-leaning individuals might be surprised to learn that, in academic circles, Jefferson is depicted as a proto-soc- ialist, the advocate of simple majority rule, and a powerful enemy of the wicked “possessive individualism” that permeated the revolution- ary period and the early republic. *Department Giuridico-Politico, Università di Milano, Italy. This article was completed in the summer of 2003 during a fellowship at the International Center for Jefferson Studies, Monticello, Va. I gladly acknowl- edge financial support and help from such a fine institution. luigi.bassani@ unimi.it. 1Frédéric Bastiat, “Property and Law,” in Selected Essays on Political Econ- omy, trans. Seymour Cain, ed. George B. de Huszar (Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Foundation for Economic Education, 1964), p. 97. 2E.g., “The Liberty Poll,” Liberty 13, no. 2 (February 1999), p. 26: “The thinker who most influenced our respondents’ intellectual development was Ayn Rand. -

Classical Rhetoric in America During the Colonial and Early National Periods

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Communication Scholarship Communication 9-2011 “Above all Greek, above all Roman Fame”: Classical Rhetoric in America during the Colonial and Early National Periods James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/comm_facpub Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Cultural History Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation James M. Farrell, "'Above all Greek, above all Roman fame': Classical Rhetoric in America during the Colonial and Early National Periods," International Journal of the Classical Tradition 18:3, 415-436. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Above all Greek, above all Roman Fame”: Classical Rhetoric in America during the Colonial and Early National Periods James M. Farrell University of New Hampshire The broad and profound influence of classical rhetoric in early America can be observed in both the academic study of that ancient discipline, and in the practical approaches to persuasion adopted by orators and writers in the colonial period, and during the early republic. Classical theoretical treatises on rhetoric enjoyed wide authority both in college curricula and in popular treatments of the art. Classical orators were imitated as models of republican virtue and oratorical style. Indeed, virtually every dimension of the political life of early America bears the imprint of a classical conception of public discourse. -

Political Legacy: John Locke and the American Government

POLITICAL LEGACY: JOHN LOCKE AND THE AMERICAN GOVERNMENT by MATTHEW MIYAMOTO A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science January 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Matthew Miyamoto for the degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Political Science to be taken January, 2016 Title: Political Legacy: John Locke and the American Government Professor Dan Tichenor John Locke, commonly known as the father of classical liberalism, has arguably influenced the United States government more than any other political philosopher in history. His political theories include the quintessential American ideals of a right to life, liberty, and property, as well as the notion that the government is legitimized through the consent of the governed. Locke's theories guided the founding fathers through the creation of the American government and form the political backbone upon which this nation was founded. His theories form the foundation of principal American documents such as the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, and they permeate the speeches, writings, and letters of our founding fathers. Locke's ideas define our world so thoroughly that we take them axiomatically. Locke's ideas are our tradition. They are our right. This thesis seeks to understand John Locke's political philosophy and the role that he played in the creation of the United States government. .. 11 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Dan Tichenor for helping me to fully examine this topic and guiding me through my research and writing. -

More- EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS ICONIC IMAGES of AMERICANS: Houdon's Portraits of Great American Leaders and Thinkers of the Enli

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS ICONIC IMAGES OF AMERICANS: Houdon’s portraits of great American leaders and thinkers of the Enlightenment reflect the close ties between France and the United States during and after the Revolutionary War. His depictions of America’s founders created lasting images that are widely reproduced to this day. • Thomas Jefferson (1789) is a marble bust that has literally shaped the world’s image of Jefferson, portraying him as a sensitive, intellectual, aristocratic statesman with a resolute, determined gaze. This sculpture has served as the model for numerous other portraits of Jefferson, including the profile on the modern American nickel. Jefferson considered Houdon the finest sculptor of his day, and acquired several of the artist’s busts of famous men—including Washington, Franklin, John Paul Jones, Lafayette, and Voltaire—to create a “gallery of worthies” at his home, Monticello, in Virginia. He sat for his own portrait at Houdon’s studio in Paris in 1789 at the age of 46. This piece is on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. • George Washington (late 1780s), a portrait of America’s first president, is a marble bust, one of several Washington portraits created by Houdon. The most famous, and considered by Houdon to be the most important commission of his career, is the full-length statue of Washington that commands the rotunda of the capitol building of the State of Virginia. Both Jefferson and Franklin recommended Houdon for the commission, and the sculptor traveled with Franklin from Paris to Mount Vernon in 1785 to visit Washington, make a life mask, and take careful measurements. -

Jeffersonian Racism

MALTE HINRICHSEN JEFFERSONIAN RACISM JEFFERSONIAN RACISM Universität Hamburg Fakultät für Wirtschafts - und Sozialwissenschaften Dissertation Zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Wirtschafts - und Sozialwissenschaften »Dr. phil.« (gemäß der Promotionsordnung v o m 2 4 . A u g u s t 2 0 1 0 ) vorgelegt von Malte Hinrichsen aus Bremerhaven Hamburg, den 15. August 2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Wulf D. Hund Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Olaf Asbach Datum der Disputation: 16. Mai 2017 - CONTENTS - I. Introduction: Studying Jeffersonian Racism 1 II. The History of Jeffersonian Racism 25 1. ›Cushioned by Slavery‹ – Colonial Virginia 30 1.1 Jefferson and his Ancestors 32 1.2 Jefferson and his Early Life 45 2. ›Weaver of the National Tale‹ – Revolutionary America 61 2.1 Jefferson and the American Revolution 62 2.2 Jefferson and the Enlightenment 77 3. ›Rising Tide of Racism‹ – Early Republic 97 3.1 Jefferson and Rebellious Slaves 98 3.2 Jefferson and Westward Expansion 118 III. The Scope of Jeffersonian Racism 139 4. ›Race, Class, and Legal Status‹ – Jefferson and Slavery 149 4.1 Racism and the Slave Plantation 159 4.2 Racism and American Slavery 188 5. ›People plus Land‹ – Jefferson and the United States 211 5.1 Racism and Empire 218 5.2 Racism and National Identity 239 6. ›The Prevailing Perplexity‹ – Jefferson and Science 258 6.1 Racism and Nature 266 6.2 Racism and History 283 IV. Conclusion: Jeffersonian Racism and ›Presentism‹ 303 Acknowledgements 315 Bibliography 317 Appendix 357 I. Introduction: Studying Jeffersonian Racism »Off His Pedestal«, The Atlantic Monthly headlined in October 1996, illustrating the bold claim with a bust of Thomas Jefferson being hammered to the floor. -

First Principles Foundational Concepts to Guide Politics and Policy

FIRST PRINCIPLES FOUNDATIONAL CONCEPTS TO GUIDE POLITICS AND POLICY NO. 70 | SEptEMBER 30, 2018 The Rise and Fall of Political Parties in America Joseph Postell Abstract Political parties are not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. Nevertheless, America’s founders understood that the republic they were founding requires parties as a means for keeping government accountable to the people. Throughout America’s history, the power of political parties has risen and fallen, reaching their nadir in the last few decades. Americans today attribute to parties the very maladies from which great parties would save us if only we would restore them. Great political parties of the past put party principles above candidate personalities and institutionalized resources to maintain coalitions based on principle. They moderated politics and provided opportunities for leadership in Congress instead of shifting all power to the executive, enabling the republic to en- joy the benefits of checks and balances while avoiding excessive gridlock. Parties also encouraged elected officials to put the national interest ahead of narrow special interests. f there is one thing about politics that unites perceived as “the establishment.” Americans are IAmericans these days, it is their contempt for bipartisan in their condemnation of partisanship. political parties and partisanship. More Americans Americans have always viewed political parties with today identify as independents than with either of skepticism. The Constitution does not mention parties the two major political parties. Citizens boast that and did not seem to anticipate their emergence. In spite of they “vote for the person, not for the party,” and this, however, parties play an essential role in our repub- denounce fellow citizens or representatives who lican form of government and have done so throughout blindly toe the party line. -

Thomas Jefferson Worksheets Thomas Jefferson Facts

Thomas Jefferson Worksheets Thomas Jefferson Facts Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) was one of America’s Founding Fathers. He is credited as the primary author of the Declaration of Independence and became the third president of the United States. EARLY AND PERSONAL LIFE ❖ Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743 in Shadwell, Virginia. He was the son of Jane Randolph Jefferson and Peter Jefferson who both came from prominent families. ❖ Young Thomas studied the Latin and Greek languages at the age of nine. ❖ In 1760, he attended the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg. It was the second oldest school in America after Harvard. He spent three years at the college before he decided to read law at Wythe. After five years, he won admission to the Virginia Bar. ❖ On January 1, 1772, Thomas married Martha Wayles Skelton, one of the wealthiest women in Virginia. They had six children but only two survived until adulthood. KIDSKONNECT.COM Thomas Jefferson Facts POLITICAL CAREER ❖ In 1768, he was elected to the House of Burgesses along with Patrick Henry and George Washington. Six years later, he had his first major political work, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America”. He attended the Second Continental Congress in 1775. ❖ Jefferson was one of the five-man committee who drafted the Declaration of Independence along with John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. He was considered as the primary author of the well-known American document wherein about 75% of his original draft was retained. ❖ In 1777, after returning to Virginia as a member of the House of Delegates, he wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.