Past Flowing to Present and Future Along the Upper Mississippi by John Crippen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Split Rock Lighthouse OPEN TO: This Job Is Open to All Applicants

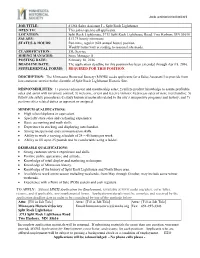

JOB ANNOUNCEMENT JOB TITLE: #1264 Sales Assistant I – Split Rock Lighthouse OPEN TO: This job is open to all applicants. LOCATION: Split Rock Lighthouse, 3713 Split Rock Lighthouse Road, Two Harbors, MN 55616 SALARY: $13.73 hourly minimum STATUS & HOURS: Part-time, regular (624 annual hours) position. Weekly hours vary according to seasonal site needs. CLASSIFICATION: 55L Service HIRING MANAGER: Store Manager II POSTING DATE: February 10, 2016 DEADLINE DATE: The application deadline for this position has been extended through April 8, 2016. SUPPLEMENTAL FORMS: REQUIRED FOR THIS POSITION. DESCRIPTION: The Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) seeks applicants for a Sales Assistant I to provide front line customer service to the clientele of Split Rock Lighthouse Historic Site. RESPONSIBILITIES: 1) process admission and membership sales; 2) utilize product knowledge to assure profitable sales and assist with inventory control; 3) welcome, orient and receive visitors; 4) process sales of store merchandise; 5) follow site safety procedures; 6) study historical materials related to the site’s interpretive programs and history; and 7) perform other related duties as apparent or assigned. MINIMUM QUALIFICATIONS: High school diploma or equivalent. Specialty store sales and cashiering experience. Basic accounting and math skills. Experience in stocking and displaying merchandise. Strong interpersonal and communication skills. Ability to work a varying schedule of 24 – 40 hours per week. Ability to lift up to 25 pounds and be comfortable using a ladder. DESIRABLE QUALIFICATIONS: Strong customer service experience and skills. Positive public appearance and attitude. Knowledge of retail display and marketing techniques. Knowledge of Minnesota history. Knowledge of the history of Split Rock Lighthouse and North Shore area. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund January 2011 Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director . 1 Overview . 2 Feature Stories on Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF) History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Initiatives Inspiring Students and Teachers . 6 Investing in People and Communities . 10 Dakota and Ojibwe: Preserving a Legacy . .12 Linking Past, Present and Future . .15 Access For Everyone . .18 ACHF History Appropriations Language . .21 Full Report of ACHF History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Statewide Initiatives Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 23 Statewide Historic Programs . 75 Statewide History Partnership Projects . 83 “Our Minnesota” Exhibit . .91 Survey of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 92 Minnesota Digital Library . 93 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $18,400 Upon request the 2011 report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of the 2011 report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2011 report is available at the Society’s website: www.mnhs.org/legacy. COVER IMAGES, CLOCKWIse FROM upper-LEFT: Teacher training field trip to Oliver H. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy

January 2019 Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects Supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Letter from MNHS CEO and Director In July 2018, I was thrilled to take on the role of the Minnesota Historical Society’s executive director and CEO. As a newcomer to the state, over the last six months, I’ve quickly noticed how strongly Minnesotans value their communities and how proud they are to be from Minnesota. The passage of the Clean Water, Land, and Legacy Amendment in 2008 clearly demonstrates this. I’m inspired by the fact that 10 years ago, Minnesotans voted to commit tax dollars to bettering their state for the future, including preserving our historical and cultural heritage. I’m proud that over 10 years, MNHS has been able to oversee a surge of communities engaging with their local history in new ways, thanks to the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF). As of December 2018, Minnesotans have invested $51 million in history through nearly 2,500 historical and cultural heritage grants in all 87 counties. These grants allow organizations to preserve and share stories about what makes their communities so unique through projects like oral histories, digitization, and new research. Without this funding, this important history can quickly be lost to time. A great example is the Hotel Sacred Heart—explored in our featured stories section —a 1914 hotel on the National Register of Historic Places that’s sat unused since the 1990s. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

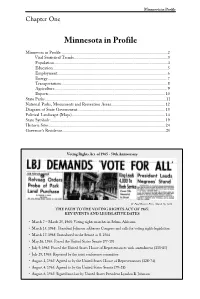

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Minneapolis Riverfront History: Map and Self-Guided Tour (PDF)

The story of Minneapolis begins at the Falls of MEET MINNEAPOLIS MAP & SELF-GUIDED TOUR St. Anthony, the only major waterfall on the VISITOR CENTER Mississippi River. Owamniyomni (the falls) has 505 Nicollet Mall, Suite 100, Minneapolis, MN 55402 612-397-9278 • minneapolis.org been a sacred site and a gathering place for the Minneapolis Dakota people for many centuries. Beginning in Meet Minneapolis staff are available in-person or over the phone at 612-397-9278 to answer questions from visitors, the 19th century the falls attracted businessmen Riverfront share visitor maps, and help with suggestions about who used its waterpower for sawmills and flour things to do in Minneapolis and the surrounding area. mills that built the city and made it the flour The Minnesota Makers retail store features work from History more than 100 Minnesota artists. milling capital of the world from 1880-1930. The riverfront today is home to parks, residences, arts Mon–Fri 10 am–6 pm Sat 10 am–5 pm and entertainment, museums, and visitor centers. Sun 10 am–6 pm Explore the birthplace of Minneapolis with this UPPER ST. ANTHONY FALLS self-guided tour along the Mississippi River, LOCK AND DAM with stops at the Upper St. Anthony Falls 1 Portland Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55401 Lock and Dam and Mill City Museum. 651-293-0200 • nps.gov/miss/planyourvisit/uppestan.htm St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam provides panoramic 1 NICOLLET MALL - HEART OF DOWNTOWN MINNEAPOLIS views of the lock and dam, St. Anthony Falls, and the Meet Minneapolis Visitor Center surrounding mill district. -

2013 MNHS Legacy Report (PDF)

Minnesota History: Building A Legacy JAnuAry 2013 | Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director and CEO . 1 Introduction . 2 Feature Stories on FY12–13 History Programs, Partnerships, Grants and Initiatives Then Now Wow Exhibit . 7 Civil War Commemoration . 9 U .S .-Dakota War of 1862 Commemoration . 10 Statewide History Programs . 12 Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants Highlights . 14 Archaeological Surveys . 16 Minnesota Digital Library . 17 FY12–13 ACHF History Appropriations Language . Grants tab FY12–13 Report of Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 19 FY12–13 Report of Statewide History Programs . 57 FY12–13 Report of Statewide History Partnerships . 73 FY12–13 Report of Other Statewide Initiatives Surveys of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 85 Minnesota Digital Library . 86 Civil War Commemoration . 87 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $6,413 Upon request this report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of this report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2012 report is available at the Society’s website: legacy.mnhs.org. COVER IMAGE: Kids try plowing at the Oliver H. Kelley Farm in Elk River, June 2012 Letter from the Director and CEO January 15, 2013 As we near the close of the second biennium since the passage of the Legacy Amendment in November 2008, Minnesotans are preserving our past, sharing our state’s stories and connecting to history like never before. -

MPTA Legacy Reporting at a Glance

Table of Contents Introduction .........................................................................................................................................3 MPTA Legacy Reporting at a Glance .................................................................................................4 WDSE•WRPT, Duluth/Superior/The Iron Range ................................................................................5 Twin Cities Public Television, Minneapolis/Saint Paul ........................................................................7 Prairie Public Broadcasting, Moorhead/Crookston ............................................................................9 Pioneer Public Television, Appleton/Worthington/Fergus Falls .......................................................11 Lakeland Public Television, Bemidji/Brainerd ...................................................................................13 KSMQ Public Service Media, Austin/Rochester ...............................................................................15 APPENDIX .......................................................................................................................................17 Appendix A - WDSE•WRPT, Duluth/Superior/The Iron Range ...........................................18 Financial Reports (07/01/2012 - 06/30/2013 and 07/01/2013 - 06/30/2015) ..............30 Appendix B - Twin Cities Public Television Raw Data ........................................................35 Financial Reports (07/01/2012 - 06/30/2013 and 07/01/2013 -

Junior Ranger Program, Mississippi National River and Recreation Area

Mississippi National River National Park Service and Recreation Area U.S. Dept. of Interior Mississippi National River and Recreation Area www.nps.gov/miss Name Age www.livetheriver.org 651-293-0200 ing! Keep Go Junior Ranger Complete all the other Junior Ranger workbooks! Program Mill Ruins Park The Mississippi River Visitor Center (in the Science Museum of Minnesota) North Mississippi Regional Park National Parks! Mill City Museum is part of a National Park called the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Over 390 National Parks all over the United States protect areas that are important to the entire country. They keep historic buildings and fields preserved, natural areas healthy for animals and plants, and preserve and tell stories that otherwise might be forgotten. What about Mill City Museum is important to the entire country? Welcome to Mill City Museum! Welcome The fun activities in this book lead you though the free spaces of the museum and will introduce you to some of the exciting history of the Mill District of Minneapolis! Use this museum map to figure out where If you need to go to complete each activity. you need help, you can ask anyone who works at the Museum. What about the Mississippi River is important to the entire country? 17 This mill had many floors of machinery. The third floor (where you Logging! picked up this book) was the The Mississippi River’s power was used for logging ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____, in addition to milling. 3 where workers put flour into barrels and sacks. -

Annual Report FISCAL YEAR 2011 President’S Letter

Annual Report FISCAL YEAR 2011 PRESIDENT’S letter By any measure, this has been a significant year for the Minnesota Historical Society. The retirement of Nina Archabal was followed by the interim leadership of Michael Fox while we completed the search for our new Executive Director. On behalf of all who have been touched by the Minnesota Historical Society, I would like again to express our deep appreciation to Nina and Michael for all they did. Our new director, Steve Elliott, comes to the Society with an extensive and impressive background and we are very happy to have him on board. Steve was drawn to the Society because of its stellar national reputation. His skills were promptly put to the test with the state shutdown and budget cuts. Steve is addressing the challenges facing the Society with the same strong leadership skills, insight and imagination that his predecessors exercised in building the Society. Our state will benefit from the continued development and excellence of the Minnesota Historical Society. An understanding of history – the problems faced before and how they were addressed – is especially important in trying times. The Minnesota Historical Society will continue to illuminate the past to shed light on the future. The Society has a remarkable staff, a dedicated governing board and a growing number of members. Thank you all for your support. William R. Stoeri, President, Minnesota Historical Society director AND CEO’S letter My service as director began May 1, and how fortunate I am to be a part of this remarkable organization. Every day I am impressed by the dedication, creativity and sheer output of the Society’s staff. -

The Future of Forestry in Minnesota's Economy

RMJ Rural Minnesota Journal The Agriculture and Forestry Issue: Looking to the Future 2009 CENTER for RURAL POLICY and DEVELOPMENT Seeking solutions for Greater Minnesota's future The Future of Forestry in Minnesota’s Economy Jim L. Bowyer Predictions of the future often first require consideration of the past and an accounting of the present. What is the situation today, how did we get here, and what are the current and emerging trends that are likely to shape tomorrow? The future of Minnesota’s forest sector will undoubtedly be informed by its turbulent past and the no-less tumultuous present. Minnesota’s forests before forestry About a half-century before professional forestry was introduced to North America, Minnesota’s forests were heavily impacted by a combination of agricultural clearing and indiscriminate logging. Forest loss was substantial, with the heaviest losses in southern Minnesota, where hardwood forests gave way to homesteads, pastures, and tilled soil. In the northern part of the state, the greatest impact on forests was due to logging. Minnesota’s first sawmill opened in 1830 in Marine on St. Croix, followed by another in Stillwater in 1840. Then activity shifted to Minneapolis, where water power could be harnessed to run the mills. By 1880, and for three decades thereafter, the state was one of the nation’s leading lumber producers. In 1900, the peak year for Minnesota lumber production, some 2.3 billion board feet of lumber (equivalent to about 4.6 million cords of wood) were sawn by an industry that employed over 15,000 people in the mills and another 23,000 felling and transporting timber.