UDA-Phase2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy

January 2019 Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects Supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Letter from MNHS CEO and Director In July 2018, I was thrilled to take on the role of the Minnesota Historical Society’s executive director and CEO. As a newcomer to the state, over the last six months, I’ve quickly noticed how strongly Minnesotans value their communities and how proud they are to be from Minnesota. The passage of the Clean Water, Land, and Legacy Amendment in 2008 clearly demonstrates this. I’m inspired by the fact that 10 years ago, Minnesotans voted to commit tax dollars to bettering their state for the future, including preserving our historical and cultural heritage. I’m proud that over 10 years, MNHS has been able to oversee a surge of communities engaging with their local history in new ways, thanks to the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF). As of December 2018, Minnesotans have invested $51 million in history through nearly 2,500 historical and cultural heritage grants in all 87 counties. These grants allow organizations to preserve and share stories about what makes their communities so unique through projects like oral histories, digitization, and new research. Without this funding, this important history can quickly be lost to time. A great example is the Hotel Sacred Heart—explored in our featured stories section —a 1914 hotel on the National Register of Historic Places that’s sat unused since the 1990s. -

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Minneapolis Riverfront History: Map and Self-Guided Tour (PDF)

The story of Minneapolis begins at the Falls of MEET MINNEAPOLIS MAP & SELF-GUIDED TOUR St. Anthony, the only major waterfall on the VISITOR CENTER Mississippi River. Owamniyomni (the falls) has 505 Nicollet Mall, Suite 100, Minneapolis, MN 55402 612-397-9278 • minneapolis.org been a sacred site and a gathering place for the Minneapolis Dakota people for many centuries. Beginning in Meet Minneapolis staff are available in-person or over the phone at 612-397-9278 to answer questions from visitors, the 19th century the falls attracted businessmen Riverfront share visitor maps, and help with suggestions about who used its waterpower for sawmills and flour things to do in Minneapolis and the surrounding area. mills that built the city and made it the flour The Minnesota Makers retail store features work from History more than 100 Minnesota artists. milling capital of the world from 1880-1930. The riverfront today is home to parks, residences, arts Mon–Fri 10 am–6 pm Sat 10 am–5 pm and entertainment, museums, and visitor centers. Sun 10 am–6 pm Explore the birthplace of Minneapolis with this UPPER ST. ANTHONY FALLS self-guided tour along the Mississippi River, LOCK AND DAM with stops at the Upper St. Anthony Falls 1 Portland Avenue Minneapolis, MN 55401 Lock and Dam and Mill City Museum. 651-293-0200 • nps.gov/miss/planyourvisit/uppestan.htm St. Anthony Falls Lock and Dam provides panoramic 1 NICOLLET MALL - HEART OF DOWNTOWN MINNEAPOLIS views of the lock and dam, St. Anthony Falls, and the Meet Minneapolis Visitor Center surrounding mill district. -

2013 MNHS Legacy Report (PDF)

Minnesota History: Building A Legacy JAnuAry 2013 | Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director and CEO . 1 Introduction . 2 Feature Stories on FY12–13 History Programs, Partnerships, Grants and Initiatives Then Now Wow Exhibit . 7 Civil War Commemoration . 9 U .S .-Dakota War of 1862 Commemoration . 10 Statewide History Programs . 12 Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants Highlights . 14 Archaeological Surveys . 16 Minnesota Digital Library . 17 FY12–13 ACHF History Appropriations Language . Grants tab FY12–13 Report of Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 19 FY12–13 Report of Statewide History Programs . 57 FY12–13 Report of Statewide History Partnerships . 73 FY12–13 Report of Other Statewide Initiatives Surveys of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 85 Minnesota Digital Library . 86 Civil War Commemoration . 87 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $6,413 Upon request this report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of this report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2012 report is available at the Society’s website: legacy.mnhs.org. COVER IMAGE: Kids try plowing at the Oliver H. Kelley Farm in Elk River, June 2012 Letter from the Director and CEO January 15, 2013 As we near the close of the second biennium since the passage of the Legacy Amendment in November 2008, Minnesotans are preserving our past, sharing our state’s stories and connecting to history like never before. -

MPTA Legacy Reporting at a Glance

Table of Contents Introduction .........................................................................................................................................3 MPTA Legacy Reporting at a Glance .................................................................................................4 WDSE•WRPT, Duluth/Superior/The Iron Range ................................................................................5 Twin Cities Public Television, Minneapolis/Saint Paul ........................................................................7 Prairie Public Broadcasting, Moorhead/Crookston ............................................................................9 Pioneer Public Television, Appleton/Worthington/Fergus Falls .......................................................11 Lakeland Public Television, Bemidji/Brainerd ...................................................................................13 KSMQ Public Service Media, Austin/Rochester ...............................................................................15 APPENDIX .......................................................................................................................................17 Appendix A - WDSE•WRPT, Duluth/Superior/The Iron Range ...........................................18 Financial Reports (07/01/2012 - 06/30/2013 and 07/01/2013 - 06/30/2015) ..............30 Appendix B - Twin Cities Public Television Raw Data ........................................................35 Financial Reports (07/01/2012 - 06/30/2013 and 07/01/2013 -

Junior Ranger Program, Mississippi National River and Recreation Area

Mississippi National River National Park Service and Recreation Area U.S. Dept. of Interior Mississippi National River and Recreation Area www.nps.gov/miss Name Age www.livetheriver.org 651-293-0200 ing! Keep Go Junior Ranger Complete all the other Junior Ranger workbooks! Program Mill Ruins Park The Mississippi River Visitor Center (in the Science Museum of Minnesota) North Mississippi Regional Park National Parks! Mill City Museum is part of a National Park called the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Over 390 National Parks all over the United States protect areas that are important to the entire country. They keep historic buildings and fields preserved, natural areas healthy for animals and plants, and preserve and tell stories that otherwise might be forgotten. What about Mill City Museum is important to the entire country? Welcome to Mill City Museum! Welcome The fun activities in this book lead you though the free spaces of the museum and will introduce you to some of the exciting history of the Mill District of Minneapolis! Use this museum map to figure out where If you need to go to complete each activity. you need help, you can ask anyone who works at the Museum. What about the Mississippi River is important to the entire country? 17 This mill had many floors of machinery. The third floor (where you Logging! picked up this book) was the The Mississippi River’s power was used for logging ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____, in addition to milling. 3 where workers put flour into barrels and sacks. -

Sustainability Metrics Presentation BECC 20121112

Integrating Sustainability Metrics into Operational and Strategic Decision-Making Lightning Session 2A: Management & Business Behavior, Energy, Climate Change Conference Sacramento, CA 12 Nov, 2012 Shengyin Xu Minnesota Historical Society Introduction Case Study Conclusion Introduction Minnesota Historical Society FOREST HISTORY CENTER SPLIT ROCK LIGHTHOUSE MILLE LACS INDIAN MUSEUM LINDBERGH NW COMPANY HISTORIC SITE FUR POST FOLSOM KELLEY FARM HOUSE METRO* MINNESOTA HISTORY CENTER MILL CITY MUSEUM FORT SNELLING FORT RIDGELY HILL HOUSE 1500 MISSISSIPPI RAMSEY HOUSE JEFFERS SIBLEY HOUSES PETROGLYPHS HISTORIC FORESTVILLE Introduction Case Study Conclusion Introduction Measuring Sustainability Utilize Metrics to Meet Challenges · Comprehensive inclusion of environmental, economic, and social impacts; · Means of understanding progress towards sustainability; · Measurements can integrate into long-term planning and operational decision-making processes. “What gets measured gets done” (attributed to Peter Drucker) (Image from Chandra Marsono via Flickr) Introduction Case Study Conclusion Minnesota Historical Society Measurements Institutional Sustainability Metric - Greenhouse gas emissions · Representation of consumption activities; · Includes carbon dioxide (most common), methane, and nitrous oxide; · Unit in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e); · Standardization protocols available by IPCC, WRI, and other organizations. Other Methods Utilized · Custom criteria for environmentally preferred purchasing - C2C and LCA; · LEED certications for renovations -

Wheat Fields, Flour Mills, and Railroads: a Web of Interdependence

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 478 396 SO 035 082 AUTHOR Koman, Rita G. TITLE Wheat Fields, Flour Mills, and Railroads: A Web of Interdependence. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. National Register of Historic Places. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 37p. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: 'http://www.cr.nps.gov/ nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/106wheat/106wheat.htm. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Historic Sites; *Industrialization; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Educational Objectives; *United States History IDENTIFIERS Interdependence; National Register of Historic Places ABSTRACT By 1860 much of the beauty of St. Anthony Falls in Minneapolis (Minnesota) had been destroyed, as mills on both sides of the river used the power of the falls to turn millions of bushels of wheat into flour. Steel rails linked bonanza farms hundreds of miles to the west to the mills. The mills, the farms, and the railroads depended on each other for success. This efficient combination dominated flour production in the United States for more than half a century. This lesson is based on National Register of Historic Places registration files and documents supplied by the Minnesota and North Dakota historical societies. The lesson could be used in relevant U.S. history, social studies, -

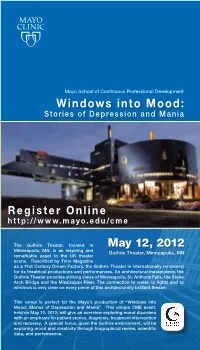

Windows Into Mood: Stories by Mail Or Fax

Mayo School of Continuous Professional Development Windows into Mood: Stories of Depression and Mania Register Online http://www.mayo.edu/cme The Guthrie Theater, located in May 12, 2012 Minneapolis, MN, is an inspiring and Guthrie Theater, Minneapolis, MN remarkable asset to the US theater scene. Described by Time Magazine as a 21st Century Dream Factory, the Guthrie Theater is internationally renowned for its theatrical productions and performances. An architectural masterpiece, the Guthrie Theater provides striking views of Minneapolis, St. Anthony Falls, the Stone Arch Bridge and the Mississippi River. The connection to water, to lights and to windows is very clear on every piece of this architecturally brilliant theater. This venue is perfect for the Mayo’s production of “Windows into Mood: Stories of Depression and Mania”. This unique CME event, held on May 12, 2012, will give an overview exploring mood disorders with an emphasis on patient stories, diagnosis, treatment intervention and recovery. A special focus, given the Guthrie environment, will be exploring mood and creativity through biographical review, scientific If you already received a copy of this brochure, please give interested an colleague. brochurethis to data, and performance. Course Description located in downtown Minneapolis The Guthrie Theater, located in on the west bank of the Mississippi Minneapolis, MN, is internationally River, next to Gold Medal Park and renowned for its theatrical the Mill City Museum. productions and has been described 818 South 2nd Street by Time Magazine as a 21st Century Minneapolis, MN 55415 Dream Factory. An architectural 612.377.2224 masterpiece, the Guthrie Theater http://www.guthrietheater.org/ provides striking views of Minneapolis, the Mississippi River, Registration St. -

August 2015 Events, Classes and Exhibits

August 2015 Events, Classes and Exhibits Saturday, Aug. 1 Time Capsule for Families: New House, 1872 Alexander Ramsey House, 265 S. Exchange St., St. Paul 1872 was an exciting year for the Ramsey family. They were able to move into their new mansion house in St. Paul. Discover what other exciting events made 1872 so important for the Ramsey's in this children's program. Children and their parents can use a timeline map to explore the Ramsey House and collect "time capsule tokens" along the way. Learn about the new foods and discover what new inventions were making life easier. Children can make their own time capsule. Phone: 651-296-8760 Time: Noon, 12:30 and 1 pm Fee: $10 adults, $9 seniors and college students, $7 ages 6-17; free for age 5 and under and MNHS members Reservations: recommended; call 651-259-3015 or register online Living History: Meet the Lindberghs Charles A. Lindbergh Historic Site, 1620 Lindbergh Dr. S., Little Falls Learn what life was like for Charles Lindbergh growing up on a farm during the First World War. Costumed characters portraying Lindbergh family members and neighbors will provide insights into young Charles’ interests in aviation, technology and nature. Hear inside stories about the Lindbergh family and have the chance to try some of the chores Charles did around the farm. Experience the life of this ordinary boy who grew up to do extraordinary things. Phone: 320-616-5421 Time: 10 am to 5 pm. Last tour leaves at 4 pm. Fee: $8 adults, $7 seniors and college students, $6 ages 6-17; free age 5 and under and MNHS members Also August 15 Civilian Conservation Corps Tour Fort Ridgely, 72404 County Road 30, Fairfax The Civilian Conservation Corps was an essential part of the Great Depression. -

Annual Report This Document Is Made Available Electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library As Part of an Ongoing Digital Archiving Project

Fiscal Year 2013 Annual Report This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp PReSident’S letteR Each year, members of the Minnesota Historical Society Executive, Emeritus and Honorary Councils are invited on a two-day bus tour of historical venues in various parts of our state. Each year, I return from this trip impressed and energized by the beautiful and fascinating sites and by the remarkable appreciation for history displayed by citizens across this state. This year we visited sites in southeast Minnesota, including the Anderson Center in Red Wing, historic downtown Red Wing and Wabasha, the Goodhue County Historical Society, the new centers for the Winona County Historical Society and the Steele County Historical Society, Historic Forestville, Louis Sullivan’s National Farmer’s Bank in Owatonna and the Minnesota State Public School for Dependent and Neglected Children in Owatonna. All of these buildings and sites were impressive, but most impressive were the people dedicated to preserving and displaying the remarkable history connected to these places. As I learned from past tours, such interesting places and dedicated people can be found in every part of our state. This helps explain why the Minnesota Historical Society is exceptional when compared to other state historical societies across the country in terms of number of members, support from members, great sites and great programming. As you will see in our Annual Report, the Minnesota Historical Society had an excellent year. We saw an increase this year in overall attendance at sites and museums, we had over three million visits to our website and we reached the milestone of 24,000 member households.