The Future of Forestry in Minnesota's Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy

January 2019 Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects Supported by the Legacy Amendment’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund Letter from MNHS CEO and Director In July 2018, I was thrilled to take on the role of the Minnesota Historical Society’s executive director and CEO. As a newcomer to the state, over the last six months, I’ve quickly noticed how strongly Minnesotans value their communities and how proud they are to be from Minnesota. The passage of the Clean Water, Land, and Legacy Amendment in 2008 clearly demonstrates this. I’m inspired by the fact that 10 years ago, Minnesotans voted to commit tax dollars to bettering their state for the future, including preserving our historical and cultural heritage. I’m proud that over 10 years, MNHS has been able to oversee a surge of communities engaging with their local history in new ways, thanks to the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF). As of December 2018, Minnesotans have invested $51 million in history through nearly 2,500 historical and cultural heritage grants in all 87 counties. These grants allow organizations to preserve and share stories about what makes their communities so unique through projects like oral histories, digitization, and new research. Without this funding, this important history can quickly be lost to time. A great example is the Hotel Sacred Heart—explored in our featured stories section —a 1914 hotel on the National Register of Historic Places that’s sat unused since the 1990s. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

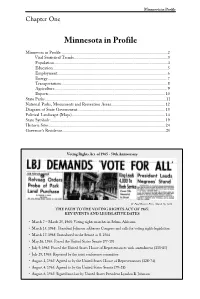

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

Sustainability Metrics Presentation BECC 20121112

Integrating Sustainability Metrics into Operational and Strategic Decision-Making Lightning Session 2A: Management & Business Behavior, Energy, Climate Change Conference Sacramento, CA 12 Nov, 2012 Shengyin Xu Minnesota Historical Society Introduction Case Study Conclusion Introduction Minnesota Historical Society FOREST HISTORY CENTER SPLIT ROCK LIGHTHOUSE MILLE LACS INDIAN MUSEUM LINDBERGH NW COMPANY HISTORIC SITE FUR POST FOLSOM KELLEY FARM HOUSE METRO* MINNESOTA HISTORY CENTER MILL CITY MUSEUM FORT SNELLING FORT RIDGELY HILL HOUSE 1500 MISSISSIPPI RAMSEY HOUSE JEFFERS SIBLEY HOUSES PETROGLYPHS HISTORIC FORESTVILLE Introduction Case Study Conclusion Introduction Measuring Sustainability Utilize Metrics to Meet Challenges · Comprehensive inclusion of environmental, economic, and social impacts; · Means of understanding progress towards sustainability; · Measurements can integrate into long-term planning and operational decision-making processes. “What gets measured gets done” (attributed to Peter Drucker) (Image from Chandra Marsono via Flickr) Introduction Case Study Conclusion Minnesota Historical Society Measurements Institutional Sustainability Metric - Greenhouse gas emissions · Representation of consumption activities; · Includes carbon dioxide (most common), methane, and nitrous oxide; · Unit in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e); · Standardization protocols available by IPCC, WRI, and other organizations. Other Methods Utilized · Custom criteria for environmentally preferred purchasing - C2C and LCA; · LEED certications for renovations -

Ready for Fun in '21?

READY FOR FUN IN ‘21? 2021 MEMORY MAKER NEW 2021 TOUR DISCOUNT Pay deposit on any tour before 1/31/21 and get the best discount of the year - 10% up to $200 per person! CASH DISCOUNTS If you pay for ANY tour with a check, money order or cash, you will receive a 3% discount. For additional questions regarding discounts, please call 1.888.845.9582. TRIP INSURANCE General We strongly encourage you to consider trip insurance to help with financial cover- age in the unlikely event of unforeseen complications. We work with an industry Information & leader in travel insurance to bring reasonable rates based upon the price of the tour (not your age) and has various add on options to basic packages for your specific considerations. If you choose to utilize trip insurance with our partner Details company and have pre-existing health conditions you wish to be covered for, you must take out trip insurance within 21-days of paying your tour deposit. TO FLY ON AN AIRPLAN E YOUR TOUR INCLUDES Tours featuring this symbol will involve a flight. • Deluxe Transportation Each traveler must present a REAL ID compliant driver’s license or state-issued • Professional Tour Director enhanced driver’s license and for international travel, a valid passport is required. • Meals as indicated in the catalog Please note for all domestic flights, luggage fees are not figured into the cost of • Gratuities for luggage handler, local Step-On guides, entertainers the tour and will be an additional cost payable direct to the airline upon your tick- and all meals as included in your itinerary eting process for boarding. -

The Logging Era at LY Oyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types

The Logging Era at LY oyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types Barbara Wyatt, ASLA Institute for Environmental Studies Department of Landscape Architecture University of Wisconsin-Madison Midwest Support Office National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska This report was prepared as part of a Cooperative Park Service Unit (CPSU) between the Midwest Support Office of the National Park Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The grant was supervised by Professor Arnold R. Alanen of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and administered by the Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin Madison. Cover Photo: Logging railroad through a northern Minnesota pine forest. The Virginia & Rainy Lake Company, Virginia, Minnesota, c. 1928 (Minnesota Historical Society). - -~------- ------ - --- ---------------------- -- The Logging Era at Voyageurs National Park Historic Contexts and Property Types Barbara Wyatt, ASLA Institute for Environmental Studies Department of Landscape Architecture University of Wisconsin-Madison Midwest Support Office National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 1999 This report was prepared as part of a Cooperative Park Service Unit (CPSU) between the Midwest Support Office of the National Park Service and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The grant was supervised by Professor Arnold R. Alanen of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and administered by the Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison. -

Minnesota Registry of Public Recreational Trail Mileages As of July 1, 1996

96056 Minnesota Registry of Public Recreational Trail Mileages as of July 1, 1996 (pursuant to Minnesota Statute 85.017) This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Trails & Waterways Unit, Recreation Services Section 500 Lafayette Road, Box 52, St. Paul, Minnesota 55155-4052 l....._ ________________ Pursuant to Minn. Stat. 85.017 To: Distribution List Date: November 20, 1996 From: Dan Collins, Supervisor Phone: (612) 296-6048 Recreation Services Trail Recreation Section Trails and Waterways Unit DNR Building - 500 Lafayette Road Saint Paul, Minnesota 55155-4052 Subject: 1996 Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Registry of Public Recreational Trail Mileage Enclosed you will find the latest edition of the Minnesota Registry ofPublic Recreational Trail Mileage, pursuant to Minnesota Statutes 85.017. This is the only comprehensive listing of the state's 20,000 miles of public off-road trails. Although the Registry includes bicycle, cross-country ski, hike, horse, all-terrain vehicle and snowmobile trails, only the all-terrain vehicle, cross-country ski and snowmobile trails are systematically updated annually. It reflects, in part, the July 1, 1996 information contained within the Department of Natural Resources' (DNR) recreational facility computer files. These files contain a great variety of information on trails shown in this Registry. The current report format does not have room to include all-terrain vehicle (ATV) trail information within the regular report. -

September 2015 Events, Classes and Exhibits

September 2015 Events, Classes and Exhibits Tuesday, September 1, 2015 History On-A-Schtick! at the Fair Minnesota State Fair, 1265 Snelling Avenue North, St. Paul, MN 651-288-4400 Experience a lighthearted, vaudevillian romp through Minnesota's past at the Minnesota State Fair's Schilling Amphitheater in the West End Market. This new daily show is 23 minutes of wacky fun, with sing-alongs, trivia, prizes and astonishing historical tidbits. Brought to you by the Minnesota State Fair Foundation and the Minnesota Historical Society. This event is made possible by the Legacy Amendment's Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the vote of Minnesotans on Nov. 4, 2008. 9:30 am - 10:00 am Free with State Fair admission Also September 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Tour for People with Memory Loss James J. Hill House, 240 Summit Avenue, St. Paul 651-297-2555 [email protected] Take a sensory-based tour designed for people with memory loss and their caregivers. Each themed tour highlights three rooms in the James J. Hill House and is followed by an optional social time with pastries and coffee. Tours are offered the first Tuesday of every month. Tours are made possible through funding by the Bader Foundation. 10:00 am - 11:30 am Free. Reservations required, get tickets online or call 651-259-3015 Friday, September 4, 2015 Farm Fresh Fridays Mille Lacs Indian Museum and Trading Post, 43411 Oodena Dr., Onamia 320-532-3632 [email protected] During select Fridays this summer, meet with local farmers and growers and shop for fresh fruits, vegetables, honey and other regionally grown food products. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY visited MNHS historic = 10,000 985,152 guests sites and museums up 17% over last year THE We served GALE FAMILY LIBRARY AT THE 23,967 HISTORY CENTER member MNHS Press sold households 91,079 WELCOMED print and 29,000 e-books RESEARCHERS 2.4 MILLION PEOPLE VISITED MNHS has the largest membership OUR WEBSITE We have engaged with of any other state 70,000 visitors historical society. mnhs.org on mnhs social 4.3 MILLION TIMES = 1,000 media platforms On the cover: We Are Hmong Minnesota opening at the Minnesota History Center, March 7, 2015. Back cover: 9 Nights of Music at the Minnesota History Center. MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY FISCAL YEAR 2015 AT A GLANCE arts and cultural $ heritage fund grants ,700 awarded across Minnesota 63 275 more than H D O 2,550 volunteers E U and interns T R U new items S B C RI added to the ONT 1,506 collection = 1,000 Northern Lights student textbook sold 18,995 About print and digital copies 25,000 students participated in = 1,000 65% serving now of Minnesota’s 6th graders National History Day in Minnesota 6th Grade 196,819 STUDENTS up 20% MN History Pass & chaperones at the served more than History visited on Center 25,000 up 18% children field trips at the with free access James J. all year long Hill House = 10,000 FROM THE PRESIDENT History today is, as it always has been, a powerful force in our world. Elected officials and leaders at all levels and of all persuasions make arguments based on history to justify their positions. -

Minnesota History: Building a Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund

Minnesota History: Building A Legacy Report to the Governor and the Legislature on Funding for History Programs and Projects from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund January 2011 Table of Contents Letter from the Minnesota Historical Society Director . 1 Overview . 2 Feature Stories on Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund (ACHF) History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Initiatives Inspiring Students and Teachers . 6 Investing in People and Communities . 10 Dakota and Ojibwe: Preserving a Legacy . .12 Linking Past, Present and Future . .15 Access For Everyone . .18 ACHF History Appropriations Language . .21 Full Report of ACHF History Grants, Programs, Partnerships and Statewide Initiatives Minnesota Historical and Cultural Heritage Grants (Organized by Legislative District) . 23 Statewide Historic Programs . 75 Statewide History Partnership Projects . 83 “Our Minnesota” Exhibit . .91 Survey of Historical and Archaeological Sites . 92 Minnesota Digital Library . 93 Estimated cost of preparing and printing this report (as required by Minn. Stat. § 3.197): $18,400 Upon request the 2011 report will be made available in alternate format such as Braille, large print or audio tape. For TTY contact Minnesota Relay Service at 800-627-3529 and ask for the Minnesota Historical Society. For more information or for paper copies of the 2011 report contact the Society at: 345 Kellogg Blvd W., St Paul, MN 55102, 651-259-3000. The 2011 report is available at the Society’s website: www.mnhs.org/legacy. COVER IMAGES, CLOCKWIse FROM upper-LEFT: Teacher training field trip to Oliver H. Kelley Farm, Elk River; Warroad Quilting Project participant; Lance Knuckles of Emerge Community Development inside old North Branch Library, Minneapolis; Gina Lemon, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, at Ottertail Peninsula on Leech Lake; Civilian Conservation Corps programming at Forest History Center, Grand Rapids. -

Past Flowing to Present and Future Along the Upper Mississippi by John Crippen

ISSUE TWELVE : FALL 2018 OPEN RIVERS : RETHINKING WATER, PLACE & COMMUNITY WATERY PLACES & ARCHAEOLOGY http://openrivers.umn.edu An interdisciplinary online journal rethinking the Mississippi from multiple perspectives within and beyond the academy. ISSN 2471- 190X ISSUE TWELVE : FALL 2018 The cover image is a detail from Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River From Astro- nomical and Barometrical Observations Surveys and Information by Joseph Nicolas Nicollet, 1843. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCom- mercial 4.0 International License. This means each author holds the copyright to her or his work, and grants all users the rights to: share (copy and/or redistribute the material in any medium or format) or adapt (remix, transform, and/or build upon the material) the article, as long as the original author and source is cited, and the use is for noncommercial purposes. Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place & Community is produced by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing and the University of Minnesota Institute for Advanced Study. Editors Editorial Board Editor: Jay Bell, Soil, Water, and Climate, University of Patrick Nunnally, Institute for Advanced Study, Minnesota University of Minnesota Tom Fisher, Minnesota Design Center, University Administrative Editor: of Minnesota Phyllis Mauch Messenger, Institute for Advanced Study, University of Minnesota Lewis E. Gilbert, futurist Assistant Editor: Mark Gorman, Policy Analyst, Washington, D.C. Laurie Moberg,