Amid Deserts, Steppes, and Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Addresses First Joint Session of New Kazakh Parliament

+5° / +1°C WEDNESDAY, MARCH 30, 2016 No 6 (96) www.astanatimes.com President Addresses First Exit Poll Says Nur Otan Joint Session of New Kazakh Wins Overwhelmingly as Parliament, Sets Priorities Mazhilis Retains Previous Makeup greens Birlik (Unity) grabbed mea- By Galiaskar Seitzhan ger 0.35 percent. This outcome is basically a virtual repetition of the ASTANA – President Nursultan previous parliamentary election in Nazarbayev-led Nur Otan Party January 2012, which ended with won 82 percent of the popular vote very similar results. in the parliamentary election in Turnout, however, proved strong- Kazakhstan, according to exit poll er this time setting a new record in results announced at midnight on the country’s electoral history and March 21. beating the result from four years The survey also showed the ruling ago when 75.45 percent of regis- party will be opposed by the same tered voters showed up at the polls. parties in the new convocation of Yulia Kuchinskaya, head of the President Nursultan Nazarbayev (at the speaking rostrum) addresses the first joint session of the Senate and the Mazhilis on March 25. the Mazhilis (the national legisla- Astana-based Institute of Democ- ture’s lower chamber) as it was the racy sociological survey company pro-business Ak zhol Democratic According to Kazakhstan’s Cen- niversary of independence with Nazarbayev recalled that the omy of Kazakhstan. Various social Party and leftist Communist Peo- tral Election Commission Chair- By Malika orazgaliyeva the newly elected parliament. 25th anniversary of Kazakhstan’s problems grow even in relatively ple’s Party again barely crossed the man (CEC) Kuandyk Turgankulov, Three parties and nine members independence coincided with a prosperous countries, he noted. -

O'zbekiston Respublikasi Xalq Ta'limi Vazirligi

O’ZBEKISTON RESPUBLIKASI XALQ TA’LIMI VAZIRLIGI A. QODIRIY NOMLI JIZZAX DAVLAT PEDAGOGIKA INTSITUTI TABIATSHUNOSLIK VA GEOGRAFIYA FAKULTETI GEOGRAFIYA VA UNI O’QITISH METODIKASI KAFEDRASI O’RTA OSIYO TABIIY GEOGRAFIYASI FANIDAN REFARAT MAVZU: TURON PASTTEKISLIGI. BAJARDI: 307 – GURUH TALABASI ABDULLAYEVA M QABUL QILDI: o’qituvchi: G. XOLDOROVA JIZZAX -2013 1 R E J A: Kirish I. Bob. Turon pasttekisligining tabiiy geografik tavsifi. 1.1. Geografik o’rni va rel’efi 1.2. Iqlimiy xususiyatlari. 1.3. Tuproqlari, o’simlik va hayvonot dunyosi. II. Bob. Turon pasttekisligining hududiy tavsifi. 2.1. Qizilqum va Qoraqum. 2.2. To’rg’ay Mug’ojar. 2.3. Mang’ishloq Ustyurt. Xulosa. Foydalanilgan adabiyotlar. 2 3 4 5 KIRISH. Tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirish deganda xududlarni ularni tabiiy geografik hususiyatlariga qarab turli katta-kichiklikdagi regional birliklarga ajratish tushuniladi. Tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirishda mavjud bo’lgan va taksonamik jihatdan bir-biri bilan bog’liq regional tabiiy geografik komplekislar ajratiladi, har-bir komplekis tabiatning o’ziga xos hususiyatlarini ochib beradi ular tabiatni tasvirlaydi hamda haritaga tushuriladi. Tabiiy geografik region nafaqat tabiiy sharoiti bilan balki o’ziga xos tabiiy resurslari bilan ham boshqalardan ajralib turadi. Shuning uchun tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirish har-bir hududning o’ziga xos sharoiti va reurslarini boxolashga imkon beradi. Uning ilmiy va amaliy ahamiyati, ayniqsa hozirgi vaqtda tabiatda ekologik muozanatni saqlash va ekologik muomolarni oldini olish dolzarb masala bo’lib turganda, juda kattadir. Tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirishni taksonamik birliklar sistemasi asosida amalgam oshirish mumkin. O’rta Osiyo hududini rayonlashtirish bilan ko’p olimlar shug’ulangan. Ular dastlab tarmoq tabiiy geografik; geomarfologik, iqlimiy, tuproqlar geografiyasi, geobatanik va zoogeografik rayonlashtirishga etibor berganlar. -

CG Challenge

2018/2019 Level 2 Classroom Name: Urban Geography Total: (_ /10) Questions Answers 1. A megacity refers to a city with: A) 10 million inhabitants or more B) 5 million inhabitants or more C) 15 million inhabitants or more D) 20 million inhabitants or more 2. A continuous urban area that surpasses administrative boundaries (i.e., built-up urban areas) is described as: A) City proper B) Metropolitan area C) Urban centre D) Urban agglomeration 3. What is the purpose of a greenbelt in urban design? A) To introduce new plant species to a city B) To prevent land-use conflict C) To prevent urban sprawl D) To create a forestry industry 1 2018/2019 Level 2 Classroom Name: 4. This city once started out as a fishing village and today is the most populous city in the world by metropolitan area. A) Shanghai B) Mumbai C) Karachi D) Tokyo 5. The United Nations considers five characteristics in defining an area as a slum. Which of the following is NOT one of those characteristics? A) Overcrowding B) Limited access to educational opportunities C) Poor structural quality of housing D) Inadequate access to safe water 6. This image is a portion of a public transit map for which global city? A) Paris, France B) Toronto, Canada C) London, England D) Los Angeles, United States 7. Which country has recently built large "ghost cities" that are mostly unpopulated? A) South Korea B) Japan C) China D) India 2 2018/2019 Level 2 Classroom Name: 8. A food desert is described as a community with: A) Infertile soil where food cannot be produced B) Extreme poverty C) No fast food available D) Little or no access to stores and restaurants that provide healthy and affordable foods 9. -

THE KAZAKH STEPPE Conserving the World's Largest Dry

THE KAZAKH STEPPE Conserving the world’s largest dry steppe region Photo: Chris Magin, IUCN Saryarka is an internationally significant mosaic of steppe and wetlands The Dry Steppe Region The steppe grasslands of Eurasia were once among the most extensive in the world, stretching from eastern Romania, Moldova and Ukraine in eastern Europe (often referred to as the Pontic steppe) east through Kazakhstan and western Russia). Together, the Pontic and Kazakh steppes, often collectively referred to as the Pontian steppe, comprise about 24% of the world’s temperate grasslands. They eventually link to the vast grasslands of eastern Asia extending to Mongolia, China and Siberian Russia, together creating the largest complex of temperate grasslands on earth. The remaining extent and ecological condition of these grasslands varies considerably by region. Today in eastern Europe, for example, only 3–5 % remain in a natural or near natural state, with only 0.2% protected. In contrast, the eastward extension of these steppes into Kazakhstan reveals lower levels of disturbance, where as much as 36% remain in a semi-natural or natural state. Although current levels of protection in this region are also very low, the steppes of Kazakhstan have the potential to offer significant opportunities for increased conservation and protection. The Kazakh steppe, also known as the Kirghiz steppe, is itself one of the largest dry steppe regions on the planet, covering approximately 804,500 square kilometres and extending more than 2,200 kilometres from north of the Caspian Sea east to the Altai Mountains. These grasslands lie at the southern end of the Ural Mountains, the traditional dividing line between Europe and Asia. -

The 2018 Zhetysu Expedition-Full

2018 ZHETYSU EXPEDITION The 2018 Zhetysu Expedition ‘In the footsteps of the Atkinsons through Eastern Kazakhstan’ 28 July - 10 August 2018 By Nick Fielding FRGS 1 | P a g e 2018 ZHETYSU EXPEDITION 1. Introduction In September 1848, after an arduous crossing of the desert from the small Cossack outpost of Ayaguz on the Kazakh Steppe, Thomas and Lucy Atkinson arrived in the newly-established bastion of Kopal, at the foot of the Djungar Alatau Mountains in the Zhetysu region – in Russian, Semirechye - of what is now Eastern Kazakhstan. At that time, it was usually described as Chinese Tartary - although the precise boundary between the Chinese and Russian Empires was not clearly delineated. The Djungar Alatau Mountains, some of which rise to over 5,000m, are merely outliers to the even higher peaks of the Tien Shan Mountains that today run along much of the official border between Kazakhstan and Western China. The Zhetysu region of Eastern Kazakhstan The Atkinsons had set off for this very remote region from the southern Siberian town of Barnaul in the spring of 1848, with the intention of visiting the Djungar Alatau Mountains and surrounding areas. They arrived at Kopal – 30km south-east of today’s Taldykorgan - in the wake of an 800-strong contingent of Russian Cossack troops, brought in to help pacify the local nomads and to facilitate the arrival of Russian settlers. Just six weeks after the Atkinsons arrived, Lucy Atkinson gave birth to a son, named Alatau Tamchiboulac Atkinson after the spring close to where he was born in Kopal. -

A/HRC/13/23/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/23/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 1 February 2010 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and Protection of all Human Rights, Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, including the Right to Development Report of the independent expert on minority issues Addendum Mission to Kazakhstan* ** (6 to 15 July 2009) Summary Kazakhstan has approximately 130 different ethnic groups, many of which have lived on the territory of Kazakhstan for generations. Initiatives taken by the Government in the field of minority issues have undoubtedly helped to ensure stability and respect for diversity and minority rights. These initiatives have included important policies to help preserve minority languages, establish and fund cultural associations for the preservation of ethnic cultures and traditions and the establishment of consultative bodies, the most prominent of which is the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan. The Assembly of the People, which plays a consultative or advisory role to the President, is a valuable national symbol of the recognition of minorities and the commitment of the State to the preservation of the cultural heritage of minorities. Nine seats in the lower house of Parliament are reserved for members chosen from the Assembly. However, the Assembly lacks the character of a legitimately representative body. Its membership is not constituted on a fully democratic basis and members are not, therefore, clearly accountable to their minority communities. * Late submission. ** The summary of the present report is being circulated in all official languages. The report itself, contained in the annex to the summary, is being circulated in the language of submission and in Russian only. -

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region 68 Central Asia Atlas of Natural Resources ater has long been the fundamental helped the region flourish; on the other, water, concern of Central Asia’s air, land, and biodiversity have been degraded. peoples. Few parts of the region are naturally water endowed, In this chapter, major river basins, inland seas, Wand it is unevenly distributed geographically. lakes, and reservoirs of Central Asia are presented. This scarcity has caused people to adapt in both The substantial economic and ecological benefits positive and negative ways. Vast power projects they provide are described, along with the threats and irrigation schemes have diverted most of facing them—and consequently the threats the water flow, transforming terrain, ecology, facing the economies and ecology of the country and even climate. On the one hand, powerful themselves—as a result of human activities. electrical grids and rich agricultural areas have The Amu Darya River in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan, with a canal (left) taking water to irrigate cotton fields.Upper right: Irrigation lifeline, Dostyk main canal in Makktaaral Rayon in South Kasakhstan Oblast, Kazakhstan. Lower right: The Charyn River in the Balkhash Lake basin, Kazakhstan. Water Resources 69 55°0'E 75°0'E 70 1:10 000 000 Central AsiaAtlas ofNaturalResources Major River Basins in Central Asia 200100 0 200 N Kilometers RUSSIAN FEDERATION 50°0'N Irty sh im 50°0'N Ish ASTANA N ura a b m Lake Zaisan E U r a KAZAKHSTAN l u s y r a S Lake Balkhash PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Ili OF CHINA Chui Aral Sea National capital 1 International boundary S y r D a r Rivers and canals y a River basins Lake Caspian Sea BISHKEK Issyk-Kul Amu Darya UZBEKISTAN Balkhash-Alakol 40°0'N ryn KYRGYZ Na Ob-Irtysh TASHKENT REPUBLIC Syr Darya 40°0'N Ural 1 Chui-Talas AZERBAIJAN 2 Zarafshan TURKMENISTAN 2 Boundaries are not necessarily authoritative. -

Qaraqalpaq Tilinin Imla Sqzligi

QARAQALPAQ TILININ IMLA SQZLIGI Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasi Xaliq bilimlendiriw ministrligi tarepinen tastiyiqlangan NOKIS «BILIM» 2017 Oaraaalpaq tiling imla sozlig.. Uliwma UOK: 811.512.121-35(076.3)------------- ■ S 4 bcrctug.n mektepoqiwshihn KBK: 81.2 Q ar b.um Nokis, «B.I.m» baSpaSl, Q 51 2017-jil- 348 bet. UOK: 8X1.512-121-35 (076.3) KBK: 81.2 Qar Q—51 Diiziwshiler: Madenbay Dawletov Shamshetdin Abdinazimov, Aruxan Dawletova Pikir bildiriwshiler: n.Sevdallaeva. - Filologiya ilimleriniP kandIdaiti Z. Ismaylova - Qaraqalpaqstan RespAlikasXaliq bilimlendmw ministrliginin jetekshi qanigesi. QARAQALPAQ TILININ IMLA SOZLIGI Nokis —«Bilim» — 2017 Redaktorlar S. Aytmuratova, S. Baynazarova Kork.redaktor I. Serjanov Tex. redakton B. Tunmbetov Operatorlar N. Saukieva, A. Begdullaeva Original-maketten basiwga ruqsat etilgen waqti 30.10.2017-j. Formati 60x90 '/]6. Tip «Tayms» garniturasi. Kegl 12. Ofset qagazi. Ofset baspa usilinda basildi. Kolemi 21,75 b.t. 22,6 esap b.t. Nusqasi 4000 dana. Buyirtpa № 17-677. «Bilim» baspasi. 230103. Nokis qalasi, Qaraqalpaqstan koshesi, 9. «0‘zbekiston» baspa-poligrafiyaliq doretiwshilik uyi. Tashkent, «Nawayi» koshesi, 30. © M.Dawletov ham t.b., 2017. ISBN 978-9943-4442-0-1 © «Bilim» baspasi, 2017. QARAQALPAQSTAN RESPUBLIKASI MINISTRLER KENESININ QARARl 224-san. 2016-jil 5-iyul Nokis qalasi QARAQALPAQ TILININ TIYKARGI IMLA QAGIYDALARIN TASTIYIQLAW HAQQINDA Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasi Joqargi Kenesinin 2016-jil 10-iyunde qabil etilgen «Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasimn ayinm nizamlanna ozgerisler ham qosimshalar kirgiziw haqqinda»gi 91/IX sanli qarann onnlaw maqsetinde Ministrler Kenesi qarar etedi: 1. Latin jaziwina tiykarlangan Qaraqalpaq tiliniri tiykargi imla qagiydalar jiynagi tastiyiqlansm. 2. Respublika ministrlikleri, vedomstvalari, jergilikli hakimiyat ham basqariw organlan, galaba xabar qurallari latin jaziwina tiykarlangan qaraqalpaq dipbesindegi barliq turdegi xat jazisiwlarda, baspasozde, is jiirgiziwde usi qagiydalardi engiziw boymsha tiyisli ilajlardi islep shiqsin ham amelge asirsm. -

International Geography Exam Part 2

2018 International Geography Bee 7. Which of these Washington cities is driest due to rain International Geography Exam - Part 2 shadow? A. Seattle B. Tacoma Instructions – This portion of the IGB Exam consists of C. Bellingham 100 questions. You will receive two points for a correct D. Spokane answer. You will lose one point for an incorrect answer. Blank responses lose no points. Please fill in the bubbles 8. The Karakum Desert in Central Asia is bordered by completely on the answer sheet. You may write on the what two mountain ranges? examination, but all responses must be bubbled on the A. Ural and Atlas answer sheet. Diacritic marks such as accents have been B. Caucasus and Hindu Kush omitted from place names and other proper nouns. You C. Hindu Kush and Yin have one hour to complete this set of multiple choice D. Caucasus and Ural questions. 9. All of these contain parts of the Kalahari Desert 1. Which of these best defines the term intergovernmental EXCEPT which of the following? organization? A. South Africa A. a multinational corporation B. Kenya B. a treaty with multiple nations as signatories C. Namibia C. an organization composed of sovereign states D. Botswana established by a charter or treaty D. an international aid agency 10. All of these border the Red Sea’s western shore EXCEPT which of the following? 2. Which of the following is an example of an A. Saudi Arabia intergovernmental organization? B. Egypt A. the United Nations C. Djibouti B. the International Red Cross D. Sudan C. the Quartet D. -

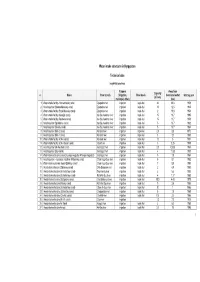

1 Water Intake Structures in Kyrgyzstan Technical Data

Water intake structures in Kyrgyzstan Technical data Issyk-Kul province Purpose Away from Capacity n Name River (canal) (irrigation, River basin river/canal outlet Start-up year (m3/sec) municipal, other) (km) 1 Water-intake facility - Komsomolsky canal Djergalan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 42 20,8 1958 2 Head regulator (Sredne-Maevsky canal) Djergalan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 10 12,5 1945 3 Water-intake facility (Staro-Maevsky canal) Djergalan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 2 19,8 1954 4 Water-intake facility (Karadjal canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 15 18,7 1995 5 Water-intake facility (Ppobeda canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 15 13,7 1959 6 Head regulator (Spiridonov canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 5 13,7 1932 7 Head regulator (Sovety canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 5 13,7 1934 8 Head regulator (M.K-2 canal) Karakol river irrigation Issyk-Kul 2,5 8,8 1970 9 Head regulator (M.K-1 canal) Karakol river irrigation Issyk-Kul 3 3,3 1965 10 Water-intake facility (M.K-6 canal) Karakol river irrigation Issyk-Kul 12 5 1957 11 Water-intake facility (M.K-4 feeder canal) Irdyk river irrigation Issyk-Kul 3 0,25 1959 12 Head regulator (Ak-Kochkor canal) Jeti-Oguz river irrigation Issyk-Kul 2,5 0,336 1954 13 Head regulator (Say canal) Jeti-Oguz river irrigation Issyk-Kul 4 11,35 1930 14 Water intake structure (canals: Levaya magistral, Pravaya magistral) Jeti-Oguz river irrigation Issyk-Kul 5 1,8 1964 15 Head regulator – automatic machine (Polyansky canal) Chon Kyzyl-Suu river irrigation -

Zhanat Kundakbayeva the HISTORY of KAZAKHSTAN FROM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN THE AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Zhanat Kundakbayeva THE HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO PRESENT TIME VOLUME I FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO 1991 Almaty "Кazakh University" 2016 ББК 63.2 (3) К 88 Recommended for publication by Academic Council of the al-Faraby Kazakh National University’s History, Ethnology and Archeology Faculty and the decision of the Editorial-Publishing Council R e v i e w e r s: doctor of historical sciences, professor G.Habizhanova, doctor of historical sciences, B. Zhanguttin, doctor of historical sciences, professor K. Alimgazinov Kundakbayeva Zh. K 88 The History of Kazakhstan from the Earliest Period to Present time. Volume I: from Earliest period to 1991. Textbook. – Almaty: "Кazakh University", 2016. - &&&& p. ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 In first volume of the History of Kazakhstan for the students of non-historical specialties has been provided extensive materials on the history of present-day territory of Kazakhstan from the earliest period to 1991. Here found their reflection both recent developments on Kazakhstan history studies, primary sources evidences, teaching materials, control questions that help students understand better the course. Many of the disputable issues of the times are given in the historiographical view. The textbook is designed for students, teachers, undergraduates, and all, who are interested in the history of the Kazakhstan. ББК 63.3(5Каз)я72 ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 © Kundakbayeva Zhanat, 2016 © al-Faraby KazNU, 2016 INTRODUCTION Данное учебное пособие is intended to be a generally understandable and clearly organized outline of historical processes taken place on the present day territory of Kazakhstan since pre-historic time. -

Climate-Proofing Cooperation in the Chu and Talas River Basins

Climate-proofing cooperation in the Chu and Talas river basins Support for integrating the climate dimension into the management of the Chu and Talas River Basins as part of the Enhancing Climate Resilience and Adaptive Capacity in the Transboundary Chu-Talas Basin project, funded by the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs under the FinWaterWei II Initiative Geneva 2018 The Chu and Talas river basins, shared by Kazakhstan and By way of an integrated consultative process, the Finnish the Kyrgyz Republic in Central Asia, are among the few project enabled a climate-change perspective in the design basins in Central Asia with a river basin organization, the and activities of the GEF project as a cross-cutting issue. Chu-Talas Water Commission. This Commission began to The review of climate impacts was elaborated as a thematic address emerging challenges such as climate change and, annex to the GEF Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, to this end, in 2016 created the dedicated Working Group on which also included suggestions for adaptation measures, Adaptation to Climate Change and Long-term Programmes. many of which found their way into the Strategic Action Transboundary cooperation has been supported by the Programme resulting from the project. It has also provided United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) the Commission and other stakeholders with cutting-edge and other partners since the early 2000s. The basins knowledge about climate scenarios, water and health in the are also part of the Global Network of Basins Working context of climate change, adaptation and its financing, as on Climate Change under the UNECE Convention on the well as modern tools for managing river basins and water Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and scarcity at the national, transboundary and global levels.