European Integration and Nuclear Deterrence After the Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GRAND STRATEGY IS ATTRITION: the LOGIC of INTEGRATING VARIOUS FORMS of POWER in CONFLICT Lukas Milevski

GRAND STRATEGY IS ATTRITION: THE LOGIC OF INTEGRATING VARIOUS FORMS OF POWER IN CONFLICT Lukas Milevski FOR THIS AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS, VISIT US AT UNITED STATES https://www.armywarcollege.edu/ ARMY WAR COLLEGE PRESS Carlisle Barracks, PA and ADVANCING STRATEGIC THOUGHT This Publication SSI Website USAWC Website SERIES The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership contributes to the education of world class senior leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. The School of Strategic Landpower develops strategic leaders by providing a strong foundation of wisdom grounded in mastery of the profession of arms, and by serving as a crucible for educating future leaders in the analysis, evaluation, and refinement of professional expertise in war, strategy, operations, national security, resource management, and responsible command. -

The Munich Massacre: a New History

The Munich Massacre: A New History Eppie Briggs (aka Marigold Black) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of BA (Hons) in History University of Sydney October 2011 1 Contents Introduction and Historiography Part I – Quiet the Zionist Rage 1. The Burdened Alliance 2. Domestic Unrest Part II – Rouse the Global Wrath 3. International Condemnation 4. The New Terrorism Conclusion 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank first and foremost Dr Glenda Sluga to whom I am greatly indebted for her guidance, support and encouragement. Without Glenda‟s sage advice, the writing of this thesis would have been an infinitely more difficult and painful experience. I would also like to thank Dr Michael Ondaatje for his excellent counsel, good-humour and friendship throughout the last few years. Heartfelt thanks go to Elise and Dean Briggs for all their love, support and patience and finally, to Angus Harker and Janie Briggs. I cannot adequately convey the thanks I owe Angus and Janie for their encouragement, love, and strength, and for being a constant reminder as to why I was writing this thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis examines the Nixon administration’s response to the Munich Massacre; a terrorist attack which took place at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. By examining the contextual considerations influencing the administration’s response in both the domestic and international spheres, this thesis will determine the manner in which diplomatic intricacies impacted on the introduction of precedent setting counterterrorism institutions. Furthermore, it will expound the correlation between the Nixon administration’s response and a developing conceptualisation of acts of modern international terrorism. -

Empathize with Your Enemy”

PEACE AND CONFLICT: JOURNAL OF PEACE PSYCHOLOGY, 10(4), 349–368 Copyright © 2004, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Lesson Number One: “Empathize With Your Enemy” James G. Blight and janet M. Lang Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies Brown University The authors analyze the role of Ralph K. White’s concept of “empathy” in the context of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vietnam War, and firebombing in World War II. They fo- cus on the empathy—in hindsight—of former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, as revealed in the various proceedings of the Critical Oral History Pro- ject, as well as Wilson’s Ghost and Errol Morris’s The Fog of War. Empathy is the great corrective for all forms of war-promoting misperception … . It [means] simply understanding the thoughts and feelings of others … jumping in imagination into another person’s skin, imagining how you might feel about what you saw. Ralph K. White, in Fearful Warriors (White, 1984, p. 160–161) That’s what I call empathy. We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions. Robert S. McNamara, in The Fog of War (Morris, 2003a) This is the story of the influence of the work of Ralph K. White, psychologist and former government official, on the beliefs of Robert S. McNamara, former secretary of defense. White has written passionately and persuasively about the importance of deploying empathy in the development and conduct of foreign policy. McNamara has, as a policymaker, experienced the success of political decisions made with the benefit of empathy and borne the responsibility for fail- Requests for reprints should be sent to James G. -

ROBERT S. MCNAMARA 9 June 1916 . 6 July 2009

ROBERT S. MCNAMARA AP PHOTO / MARCY NIGHSWANDER 9 june 1916 . 6 july 2009 PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY VOL. 160, NO. 4, DECEMBER 2016 McNamara.indd 425 1/24/2017 9:07:37 AM biographical memoirs McNamara in Winter: The Quixotic Quest of an Unquiet American He was impregnably armored by his good intentions and his ignorance. —Graham Greene, The Quiet American (1955) Sanity may be madness, but the maddest of all is to see life as it is and not as it should be. —Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote de La Mancha Errol Morris: This is a movie [“The Fog of War”] with one inter- view, but sometimes I think there are two characters: the 85-year- old McNamara speaking to the 45-year-old McNamara. Terry Gross: Yeah, I know exactly what you mean. I mean, as a viewer, this was my impression too, yeah. —National Public Radio interview on “Fresh Air,” 5 January 2004 An American Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Following Robert S. McNamara’s death on 6 July 2009, at age 93, dozens of obituaries appeared, most of them telling the same basic story. McNamara was portrayed as an American variant of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a bright and successful man but also a bad and destructive man whose pursuit of power and colossal arrogance led America and the world into the quagmire of the Vietnam War. First, Dr. Jekyll. A quick perusal of McNamara’s life seems initially to prove that the so-called “Horatio Alger Myth” is sometimes reality: rags to riches, obscurity to fame, blue collar to the corridors of power. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense : Robert S. Mcnamara

The Ascendancy of the Secretary ofJULY Defense 2013 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Cover Photo: Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, and President John F. Kennedy at the White House, January 1963 Source: Robert Knudson/John F. Kennedy Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara 1961-1963 Special Study 4 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense July 2013 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 4 The Ascendancy of the Secretary of Defense Contents This study was reviewed for declassification by the appropriate U.S. Government departments and agencies and cleared for release. The study is an official publication of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Foreword..........................................vii but inasmuch as the text has not been considered by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, it must be construed as descriptive only and does Executive Summary...................................ix not constitute the official position of OSD on any subject. Restructuring the National Security Council ................2 Portions of this work may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line in included. -

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response A Weekly Update from the UN Department of Public Information No. 100/ 24 June 2015 Syrians face “unspeakable suffering,” says UN official The Independent Commission of Inquiry on Syria released on 23 June its latest report on the human rights situation in the country, covering the period from 15 March to 15 June. Presenting the report to the Human Rights Council in Geneva, the Chair of the Commission, Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, said that the conflict in Syria had mutated into a multi-sided and highly fluid war of attrition and civilians remain the main victims of an ever-accelerating cycle of violence, which is causing “unspeakable suffering.” Mr. Pinheiro added that with its superior fire power and control of the skies, the Government inflicted the most damage in its indiscriminate attacks on civilians, and non- state armed groups continued to cause civilian deaths and injuries. The Chairman of the Commission also deplored that “the continuing war represents a profound failure of diplomacy and the absence of action by the international community had nourished a deeply entrenched culture of impunity.” http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=51227#.VYmoeEbgW3b More funding needed for Palestine refugees in Lebanon On 22 June, UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon, Sigrid Kaag, called for increased donor assistance to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) to meet the needs of Palestine refugees in Lebanon. Ms. Kaag was speaking during a visit to the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj El-Barajneh, south of Beirut. “Residents of the camp are facing enormous difficulties every day; all possible efforts should be made to give greater support to Palestine refugees here,” she said. -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood -

The Yom Kippur War: Forty Years Later

The Yom Kippur War: Forty Years Later By HIC research assistant Philip Cane Background Yom Kippur, October 6th 1973, at five minutes past two precisely, 4,000 artillery pieces, 250 aircraft and dozens of FROG missiles1 struck Israeli positions along the Suez Canal and the Sinai, at the same time along the Golan Heights 1,400 tanks2 advanced towards Israel. The equivalent of the total conventional forces of NATO in Europe3, eleven Arab nations4 led by Egypt and Syria had begun an advance into Israeli territory gained in the 1967 Six Day War. The largest Arab-Israeli War would end in an Israeli tactical victory5, but for the first week the fate of Israel itself would be doubted, ‘most Israelis still refer to it as an earthquake that changed the course of the state’s history.’6 The war changed the perceptions of all levels of society in the Middle East and forty years later its ripples are still felt to this day. The Yom Kippur War fell on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, a Saturday (the Jewish Sabbath) when the alertness of Israeli forces were notably reduced and only a skeleton force7 would be on duty with radio and TV stations shut down hampering mobilisation8. This has led some writers such as Trevor Dupuy and Chaim Herzog to state that this was the primary motive for any such attack9. But it what is not often known is that October 6th is the tenth and holiest day of Ramadan10, when the Prophet Mohammed conquered Mecca which resulted in all of Arabia being Arabic11. -

US-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas

U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42784 U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas Summary Over the past several years, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island-building and base- construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan- administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere. Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. -

Transition (1974) - Possible Candidates for Appointment to Positions (1)” of the Richard B

The original documents are located in Box 12, folder “Transition (1974) - Possible Candidates for Appointment to Positions (1)” of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 12 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE T WASHINGTON A • B A ww w DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT Gaylord Freeman Chairman of the Board First National Bank of Chicago John Robson Sheldon Lubar Resigned as Assistant Secretary, HUD for Housing Production and Mortgage Credit (old FHA job) . Policy differences with Lynn over regional offices. Former Chairman Mortgage Association, Inc. Milwaukee, Wisconsin (mortgage banking company). Rocco Siciliano President, Title Insurance in Los Angeles (lent money to buy San Clemente) . Former Commerce Undersecretary. Thomas Moody Mayor, Columbus, Ohio {Rep.) Moon Landrieu Mayor, New Orleans (Dem.) Louis Welch Houston. Retired as Mayor. Dem. conservative. Helped Nixon Administration push revenue sharing, etc., with Mayors. -

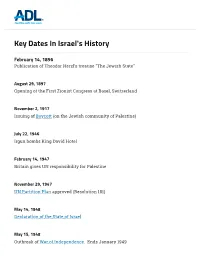

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution