Soviet Intelligence and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuban Missile Crisis JCC: USSR

asdf PMUNC 2015 Cuban Missile Crisis JCC: USSR Chair: Jacob Sackett-Sanders JCC PMUNC 2015 Contents Chair Letter…………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction……………….………………………………………………….4 Topics of Concern………………………...………………….………………6 The Space Race…...……………………………....………………….....6 The Third World...…………………………………………......………7 The Eastern Bloc………………………………………………………9 The Chinese Communists…………………………………………….10 De-Stalinization and Domestic Reform………………………………11 Committee Members….……………………………………………………..13 2 JCC PMUNC 2015 Chair’s Letter Dear Delegates, It is my great pleasure to give you an early welcome to PMUNC 2015. My name is Jacob, and I’ll be your chair, helping to guide you as you take on the role of the Soviet political elites circa 1961. Originally from Wilmington, Delaware, at Princeton I study Slavic Languages and Literature. The Eastern Bloc, as well as Yugoslavia, have long been interests of mine. Our history classes and national consciousness often paints them as communist enemies, but in their own ways, they too helped to shape the modern world that we know today. While ultimately failed states, they had successes throughout their history, contributing their own shares to world science and culture, and that’s something I’ve always tried to appreciate. Things are rarely as black and white as the paper and ink of our textbooks. During the conference, you will take on the role of members of the fictional Soviet Advisory Committee on Centralization and Global Communism, a new semi-secret body intended to advise the Politburo and other major state organs. You will be given unmatched power but also faced with a variety of unique challenges, such as unrest in the satellite states, an economy over-reliant on heavy industry, and a geopolitical sphere of influence being challenged by both the USA and an emerging Communist China. -

Babadzhanian, Hamazasp

Babadzhanian, Hamazasp Born: February 18th, 1906 Died: November 1st, 1977 (Aged 71) Ethnicity: Armenian Field of Activity: Red Army Brief Biography Hamazasp Khachaturi Babadzhanian was a Russian military general who served during multiple wars for the Soviet Union, rising to prominence during the Great Patriotic War. He was born in 1906 into an impecunious Armenian family in Chardakhlu, Azerbaijan. He attended a secondary school in Tiflis in 1915 but due to familial financial difficulties was forced to return home and toil in the fields on his family’s plot of land, later working as a highway worker during 1923-24. Babadzhanian joined the Red Army in 1925 and later attended a Military School in Yerevan in 1926, graduating as an officer in 1929, as well as joining the Soviet Communist Party in 1928. He received various postings, mopping up armed gangs in the Caucasus region in 1930 and aided in liquidating the Kulak revolt. Babadzhanian moved around frequently, generally within the Transcaucasus and Baku regions, until 1939-1940, when he served in the Finno-Soviet war. He played a pivotal role in numerous battles in World War 2, participating in the battle of Smolensk, as well as contributing a fundamentally in Yelnya, where he overcame a far superior German force. For his efforts in recapturing Stanslav he received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. He provided support in Poland, as well fighting in Berlin, contributing to the capture of the Reichstag. After the Great Patriotic War Babadzhanian would prove crucial in quelling the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and some time after in 1975 became Chief Marshal of the Tank and Armoured Troops, a rank only he and one other attained. -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Two-phase flow in rotating hele-shaw cells with coriolis effects Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52f0s67h Journal Interfaces and Free Boundaries, 15(2) ISSN 1463-9963 Authors Escher, J Guidotti, P Walker, C Publication Date 2013-10-07 DOI 10.4171/IFB/302 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Access provided by University of California, Davis (25 Mar 2013 14:58 GMT) T HE A MERICAS 69:4/April 2013/493–507 COPYRIGHT BY THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN FRANCISCAN HISTOR Y ACCIDENTAL HISTORIAN: An Interview with Arnold J. Bauer ppreciated among Latin Americanists in the United States and highly regarded in Chile, Arnold (“Arnie”) Bauer taught history at A the University of California at Davis from 1970 to 2005, and was director of the University of California’s Education Abroad Program in San- tiago, Chile, for five years between 1994 and 2005. Well-known for his engaging writing style, Bauer reflects broad interests in his publications: agrarian history (Chilean Rural Society: From the Spanish Conquest to 1930 [1975]), the Catholic Church and society (as editor, La iglesia en la economía de América Latina, siglos XIX–XIX [1986]), and material culture (Goods, Power, History: Latin America’s Material Culture [2001]). He has also written an academic mystery regarding a sixteenth-century Mexican codex, The Search for the Codex Cardona (2009). His coming-of-age memoir (Time’s Shadow: Remembering a Family Farm in Kansas [2012]) describes his childhood and was recently named one of the top five books of 2012 by The Atlantic. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Anthology of the international conference Bratislava 14. – 16. 11. 2007 Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Nation´s Memory Institute BRATISLAVA 2008 Anthology was published with kind support of The International Visegrad Fund. Visegrad Fund NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Cen- tral and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 14 – 16 November, 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia Anthology of the international conference Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Published by Nation´s Memory Institute Nám. SNP 28 810 00 Bratislava Slovakia www.upn.gov.sk 1st edition English language correction Anitra N. Van Prooyen Slovak/Czech language correction Alexandra Grúňová, Katarína Szabová Translation Jana Krajňáková et al. Cover design Peter Rendek Lay-out, typeseting, printing by Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška © Nation´s Memory Institute 2008 ISBN 978-80-89335-01-5 Nation´s Memory Institute 5 Contents DECLARATION on a conference NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 ..................................................................9 Conference opening František Mikloško ......................................................................................13 Jiří Liška ....................................................................................................... 15 Ivan A. Petranský ........................................................................................ -

China and Ballistic Missile Defense: 1955 to 2002 and Beyond

INSTITUTE FOR DEFENSE ANALYSES China and Ballistic Missile Defense: 1955 to 2002 and Beyond Brad Roberts September 2003 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. IDA Paper P-3826 Log: H 03-002053 This work was conducted under contract DASW01 98 C 0067, Task DG-6-2184, for the Defense Intelligence Agency. The publication of this IDA document does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official position of that Agency. © 2003 Institute for Defense Analyses, 4850 Mark Center Drive, Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1882 • (703) 845-2000. This material may be reproduced by or for the U.S. Government pursuant to the copyright license under the clause at DFARS 252.227-7013 (NOV 95). INSTITUTE FOR DEFENSE ANALYSES IDA Paper P-3826 China and Ballistic Missile Defense: 1955 to 2002 and Beyond Brad Roberts PREFACE This paper was prepared for a task order on China’s Approach to Missile Defense for the Defense Intelligence Agency. The objective of the task is to inform thinking within the U.S. defense community about China’s approach to missile defense issues and its implications for regional security and U.S. interests. In preparing this work, the author has benefited from excellent collaboration with Mr. Ronald Christman of DIA. The author wishes to express his gratitude to the following individuals for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this essay: Elaine Bunn of National Defense University, Ron Christman of DIA, Iain Johnston of Harvard University, Evan Medeiros of RAND, and Victor Utgoff of IDA. He also wishes to express his gratitude to Rafael Bonoan of IDA for his research support and assistance in drafting a subsection of the report. -

Alan Mcpherson on Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba's

James G. Blight, Philip Brenner. Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba's Struggle with the Superpowers after the Missile Crisis. Lanham and Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002. xxvii + 324 pp. $29.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-7425-2288-6. Reviewed by Alan McPherson Published on H-Diplo (January, 2003) "Empathy" for Cuba's Missile Crisis explained.[2] Castro himself has been making that Every few months, it seems, new evidence or case since a similar 1992 conference, not only by revelations about the Cuban Missile Crisis come to releasing new evidence but also by personally light to underscore the seriousness of that mo‐ taking part in the discussions. ment in human history. Most recently, the forti‐ Why Castro has been so willing to oversee eth-anniversary conference in Havana in October this rewriting of history is largely explained in 2002 brought Cuban leader Fidel Castro together James Blight and Philip Brenner's short but with scholars as well as surviving Kennedy and uniquely valuable book, Sad and Luminous Days: Khrushchev advisers to add still more insight into Cuba's Struggle with the Superpowers after the how close the world came to annihilation. There, Missile Crisis. Their description of Castro's bitter‐ the assembled learned, for instance, that two offi‐ ness, at what he perceived to be Nikita cers of a Soviet submarine, out of touch with Mos‐ Khrushchev's betrayal, has come out now with the cow and besieged by U.S. depth charges, had actu‐ end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the So‐ ally begun the process of launching a nuclear at‐ viet Union. -

1 a New Political Dawn: the Cuban Revolution in the 1960S

Notes 1 A New Political Dawn: The Cuban Revolution in the 1960s 1. For an outline of the events surrounding the Padilla Affair, see chapter two. 2. Kenner and Petras limited themselves to mentioning the enormous importance of a Cuban Revolution with which a great number of the North American New Left identified. They also dedicated their book to the Cuban and Vietnamese people for “giving North Americans the possibility of making a revolution” (1972: 5). 3. For an explanation of the term gauchiste and of its relevance to the New Left, see chapter six. 4. However, this consideration has been rather critical in the case of Minogue (1970). 5. The general consensus seems to be that, as the Revolution entered a period of rapid Sovietization following the failure of the ten million ton sugar harvest of 1970, Western intellectuals, who until then had showed support, sought to distance themselves from the Revolution. The single incident that seemingly sparked this reaction, in particular from some French intellectuals, was the Padilla Affair. 6. Here a clear distinction must be made mainly between the Communist Party of the pre-Revolutionary period, the Partido Socialista Popular (Popular Socialist Party) and the 26 July Movement (MR26). The former had a legacy of Popular Frontism, collaboration with Batista in the post- War period and a general distrust of “middle class adventurers” as it referred to the leadership of MR26 until 1958 (Karol, 1971: 150). The latter, led by Castro, had a radical though incoherently articulated ideo- logical basis. The process of unification of revolutionary organizations carried out between 1961 and 1965 did not completely obliterate the individuality of these competing discourses and it was in their struggle for supremacy that the New Left’s contribution was made. -

Empathize with Your Enemy”

PEACE AND CONFLICT: JOURNAL OF PEACE PSYCHOLOGY, 10(4), 349–368 Copyright © 2004, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Lesson Number One: “Empathize With Your Enemy” James G. Blight and janet M. Lang Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies Brown University The authors analyze the role of Ralph K. White’s concept of “empathy” in the context of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vietnam War, and firebombing in World War II. They fo- cus on the empathy—in hindsight—of former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, as revealed in the various proceedings of the Critical Oral History Pro- ject, as well as Wilson’s Ghost and Errol Morris’s The Fog of War. Empathy is the great corrective for all forms of war-promoting misperception … . It [means] simply understanding the thoughts and feelings of others … jumping in imagination into another person’s skin, imagining how you might feel about what you saw. Ralph K. White, in Fearful Warriors (White, 1984, p. 160–161) That’s what I call empathy. We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions. Robert S. McNamara, in The Fog of War (Morris, 2003a) This is the story of the influence of the work of Ralph K. White, psychologist and former government official, on the beliefs of Robert S. McNamara, former secretary of defense. White has written passionately and persuasively about the importance of deploying empathy in the development and conduct of foreign policy. McNamara has, as a policymaker, experienced the success of political decisions made with the benefit of empathy and borne the responsibility for fail- Requests for reprints should be sent to James G. -

'The Cuban Question' and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964

‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101153/ Version: Published Version Article: Harmer, Tanya (2019) ‘The Cuban question’ and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959-1964. Journal of Cold War Studies, 21 (3). pp. 114-151. ISSN 1520-3972 https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00896 Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ The “Cuban Question” and the Cold War in Latin America, 1959–1964 ✣ Tanya Harmer In January 1962, Latin American foreign ministers and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk arrived at the Uruguayan beach resort of Punta del Este to debate Cuba’s position in the Western Hemisphere. Unsurprisingly for a group of representatives from 21 states with varying political, socioeconomic, and geo- graphic contexts, they had divergent goals. Yet, with the exception of Cuba’s delegation, they all agreed on why they were there: Havana’s alignment with “extra-continental communist powers,” along with Fidel Castro’s announce- ment on 1 December 1961 that he was a lifelong Marxist-Leninist, had made Cuba’s government “incompatible with the principles and objectives of the inter-American system.” A Communist offensive in Latin America of “in- creased intensity” also meant “continental unity and the democratic institu- tions of the hemisphere” were “in danger.”1 After agreeing on these points, the assembled officials had to decide what to do about Cuba. -

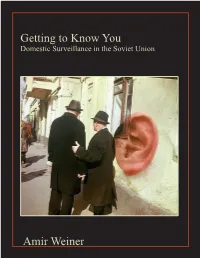

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime