Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Se-183-00 Sommario.Vp

STUDI MIGRATION EMIGRAZIONE STUDIES rivista trimestrale quarterly journal CENTRO STUDI EMIGRAZIONE - ROMA ANNO XLVIII - LUGLIO-SETTEMBRE 2011 - N. 183 SOMMARIO 150 anni della nostra storia: la pastorale agli emigrati in Europa e Australia a cura di VINCENZO ROSATO 355 – Introduzione, Vincenzo Rosato 357 – Cronologia e storia dell’emigrazione italiana, Matteo Sanfilippo 371 – Santa Sede e movimenti migratori: una lunga storia di attenzione alla persona umana, Gabriele Bentoglio 385 – Emigrazione italiana in Europa: missione e cura pastorale, Giovanni Graziano Tassello 407 – I pionieri del servizio ai migranti italiani. Gli interventi provvidenziali di Pallotti, Bosco, Scalabrini, Bonomelli e Cabrini a partire dall’Unità d’Italia, Vincenzo Rosato 427 – L’emigrazione nella memoria storica italiana. Una riflessione critica, Roberto Sala 442 – Gli italiani di Bedford: sessant’anni di vita in Inghilterra, Margherita Di Salvo 461 – Guerre fra compagni a cavallo del 1900. Il movimento socialista italiano in Svizzera ed il socialismo elvetico fra classe e nazione, Domenico Guzzo Coordinatore editoriale: Matteo Sanfilippo - Centro Studi Emigrazione - Roma 2011 477 – L’emigrazione italiana in Australia, Fabio Baggio, Matteo Sanfilippo 500 – Identity and cultural maintenance: Observations from a case study of third-generation Italian-Australians in South Australia, Melanie Smans, Diana Glenn 515 – Recensioni 524 – Segnalazioni 354 «Studi Emigrazione/Migration Studies», XLVIII, n. 183, 2011. Introduzione Gli ultimi 150 anni della storia italiana sono stati attraversati da numerose vicende, che hanno segnato profondamente le sorti della na- zione. Il grande sforzo di unificare il paese non ha, però, corrisposto al desiderio pressante di creare un unico popolo, anzi fin dall’inizio l’Ita- lia come il resto dell’Europa ha visto la partenza di tanti, che si sono sparsi per tutti i continenti. -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

A Renunciation of Nuclear Weapons One Citizen at a Time

If governments derive their powers from the consent of the governed, as stated in the U.S. Declaration of Independence, then to what degree am I, as a citizen, morally, legally and spiritually responsible for the acts, and plans to act, of my government? Hiroshima -- August 1945 Baghdad -- 2004 ??? A Renunciation of Nuclear Weapons One Citizen At A Time Documents in support of United States citizens renouncing the use of nuclear weapons on their behalf a reference guide in support of study, reflection, prayer and protest Compiled and edited by Dennis Rivers with the cooperation of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation and the Peacemaker Community Santa Barbara, California -- March 30, 2002 this document is available free of charge on the web at www.nonukes.org Dedicated to the children of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, August 1945. May we learn something from your suffering about our own capacity to not see what is before us, something we desperately need to understand about ourselves. And thus may you, even in death, be eternal protectors of life. And with great appreciation to these “friends of all life” for their courage, deep insight and luminous teaching by example Joanna Macy, Gene Knudsen Hoffman, Paloma Pavel, the late Walter Capps, Mayumi Oda, Ramon Panikkar, David Krieger, David Hartsough and Kazuaki Tanahashi A Renunciation of Nuclear Weapons One Citizen At A Time TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction. By Dennis Rivers 1 A brief citizen’s declaration regarding the use of nuclear 3 weapons Declaration of a United States Citizen Concerning the Use of 4 Nuclear Weapons by the United States (full-page version) Sample Paragraphs for Cover Letter to Elected Officials 6 Suggested Next Steps: Where to send copies of your 7 declaration and groups you can support that are working on the nuclear weapons issue Religious Organizations and Leaders on Nuclear Weapons and 8 Abolition (from www.nuclearfiles.org) Statement of Rabbi David Saperstein, Director, Religious 12 Action Center of Reform Judaism, On Nuclear Reduction/Disarmament 75 U.S. -

The Catholic Prelature of Sts. Peter and Paul 12 Catherwood Street, Tewksbury, MA 01876‐2620, USA Tel

Mt. Rev. William J. Manseau, SBM, D.Min. Married Priests Now! The Catholic Prelature of Sts. Peter and Paul 12 Catherwood Street, Tewksbury, MA 01876‐2620, USA Tel. 978‐851‐5547 April 27, 2014 Divine Mercy Sunday Apostles of Mercy: A Reflection on the Married Priests Now! Prophetic Mission of Archbishop Emmanuel Milingo, Emeritus Archbishop of Lusaka, Zambia and the Canonizations of Popes John XXIII and John Paul II by Pope Francis Emmanuel Milingo was consecrated as a bishop for service in the Roman Catholic Church on August 1, 1969 by Pope Paul VI, Giovanni Batista Montini at Kololo Terrace, Kampala, Uganda following his election as Archbishop of Lusaka where he served from 1969 to 1983 as one of Africa’s youngest bishops. He experienced and developed a charismatic, Biblically based healing ministry and in 1976 he joined the Catholic charismatic renewal movement finding therein a link between his African heritage and his Catholic faith. The Second Vatican Council had revisited the question of charisms in the Church. As Leon Joseph Cardinal Suenens stated: “In regard to charisms, the Council adopted an open and receptive attitude expressed in a balanced text indicating that, providing that necessary prudence be observed, charisms should be recognized and esteemed in the Church of today. Indeed we might add: they are more important than ever before.” (A New Pentecost? Seabury Press, NY, 1975, p.30). Cardinal Suenens had been appointed by Pope Paul VI to oversee the world wide Roman Catholic Charismatic Renewal. Following his ordination as a priest in 1958, with additional education in Rome and Dublin, he became a champion of enculturation, espoused by Vatican II and later Pope John Paul II, working for the development of an authentic African Christianity expressed through indigenous spiritual and cultural symbols. -

From Archives of Vuchk-GPU-NKVD-KGB Chernobyl Tragedy in Documents and Materials (Summary)

From Archives of VUChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB Chernobyl Tragedy in Documents and Materials (Summary) Volodymyr Tykhyy General overview of the book The book "From archives of VUChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB. Chernobyl tragedy in documents and materials" (Z arhiviv VUCHK-GPU-NKVD-KGB. Chornobylska tragedia v dokumentakh ta materialakh, №1(16) 2001) was published by the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) in 2001. SSU is a natural continuation of the Soviet KGB (Committee of the State Security of the USSR), so SSU inherited KGB archives and disclosed some documents when the appropriate legislation was passed by the Parliament of Ukraine beginning in 1994 with the Law "On State Secrets". It is essential to note that on 10 December 2005 the book was also posted on the web-site of the SSU (http://www.sbu.gov.ua/sbu/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=39296&cat_id=46616). KGB is a unique source of information, because it worked "across the lines": it was subordinated neither to nuclear industry nor to army generals; it supervised activities of industry, government and municipal authorities, construction companies and cooperative shops alike. KGB officers collected information from all sources they deemed reliable, they often were able to cross-check it and then to present to higher levels of hierarchy - in KGB, Communist Party, Government of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. So, this information contained quite reliable facts, which were formulated without flatter - moreover, it was either "secret" or "top secret". Unfortunately, this does not mean that their reports were given any special attention - the system had its own inertia, and KGB was an integral part of the system. -

H-Diplo Article Roundtable Review, Vol. X, No. 24

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Article Roundtable Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Review Introduction by Thomas Maddux www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Reviewers: Bruce Craig, Ronald Radosh, Katherine A.S. Volume X, No. 24 (2009) Sibley, G. Edward White 17 July 2009 Response by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr Journal of Cold War Studies 11.3 (Summer 2009) Special Issue: Soviet Espoinage in the United States during the Stalin Era (with articles by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr; Eduard Mark; Gregg Herken; Steven T. Usdin; Max Holland; and John F. Fox, Jr.) http://www.mitpressjournals.org/toc/jcws/11/3 Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-24.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge.............................. 2 Review by Bruce Craig, University of Prince Edward Island ..................................................... 8 Review by Ronald Radosh, Emeritus, City University of New York ........................................ 16 Review by Katherine A.S. Sibley, St. Josephs University ......................................................... 18 Review by G. Edward White, University of Virginia School of Law ........................................ 23 Author’s Response by John Earl Haynes, Library of Congress, and Harvey Klehr, Emory University ................................................................................................................................ 27 Copyright © 2009 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

20Th Century Mass Graves Proceedings of the International Conference Tbilisi, Georgia, 15 to 17 October 2015

IPE International Perspectives 74 in Adult Education 20th Century Mass Graves Proceedings of the International Conference Tbilisi, Georgia, 15 to 17 October 2015 Matthias Klingenberg / Arne Segelke (Editors) International Perspectives in Adult Education – IPE 74 The reports, studies and materials published in this series aim to further the develop- ment of theory and practice in adult education. We hope that by providing access to information and a channel for communication and exchange, the series will serve to increase knowledge, deepen insights and improve cooperation in adult education at international level. © DVV International 2016 Publisher: DVV International Institut für Internationale Zusammenarbeit des Deutschen Volkshochschul-Verbandes e. V. Obere Wilhelmstraße 32, 53225 Bonn, Germany Tel.: +49 (0)228 97569 - 0 / Fax: +49 (0)228 97569 - 55 [email protected] / www.dvv-international.de DVV International is the Institute for International Cooperation of the Deutscher Volkshochschul-Verband e. V. (DVV), the German Adult Education Association. As the leading professional organisation in the field of Adult Education and development cooperation, DVV International provides worldwide support for the establishment and development of sustainable structures for Youth and Adult Education. Responsible: Christoph Jost Editors: Matthias Klingenberg/Arne Segelke Managing Editor: Gisela Waschek Opinions expressed in papers published under the names of individual authors do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher and editors. This publication, or parts of it, may be reproduced provided the source is duly cited. The publisher asks to be provided with copies of any such reproductions. The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available at http://dnb.ddb.de ISBN: 978-3-942755-31-3 Corporate design: Deutscher Volkshochschul-Verband e.V. -

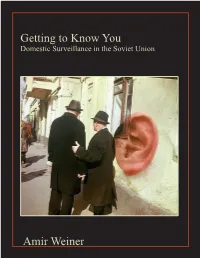

Getting to Know You. the Soviet Surveillance System, 1939-1957

Getting to Know You Domestic Surveillance in the Soviet Union Amir Weiner Forum: The Soviet Order at Home and Abroad, 1939–61 Getting to Know You The Soviet Surveillance System, 1939–57 AMIR WEINER AND AIGI RAHI-TAMM “Violence is the midwife of history,” observed Marx and Engels. One could add that for their Bolshevik pupils, surveillance was the midwife’s guiding hand. Never averse to violence, the Bolsheviks were brutes driven by an idea, and a grandiose one at that. Matched by an entrenched conspiratorial political culture, a Manichean worldview, and a pervasive sense of isolation and siege mentality from within and from without, the drive to mold a new kind of society and individuals through the institutional triad of a nonmarket economy, single-party dictatorship, and mass state terror required a vast information-gathering apparatus. Serving the two fundamental tasks of rooting out and integrating real and imagined enemies of the regime, and molding the population into a new socialist society, Soviet surveillance assumed from the outset a distinctly pervasive, interventionist, and active mode that was translated into myriad institutions, policies, and initiatives. Students of Soviet information systems have focused on two main features—denunciations and public mood reports—and for good reason. Soviet law criminalized the failure to report “treason and counterrevolutionary crimes,” and denunciation was celebrated as the ultimate civic act.1 Whether a “weapon of the weak” used by the otherwise silenced population, a tool by the regime -

Prenesi Datoteko Prenesi

ISSN 0351-1189 PRIMERJALNA KNJIŽEVNOST ISSN 0351-1189 RAZPRAVE Comparative literature, Ljubljana PKn (Ljubljana) 37.3 (2014) 37.3 PKn (Ljubljana) Tomaž Toporišič: Nevarna razmerja »mlade slovenske umetnosti« in PKn (Ljubljana) 37.3 (2014) 37.3 PKn (Ljubljana) PKn (Ljubljana) 37.3 (2014) futurizma Izdaja Slovensko društvo za primerjalno književnost Igor Žunkovič: Strnišev lirski subjekt Published by the Slovene Comparative Literature Association www.zrc-sazu.si/sdpk/revija.htm Alojzija Zupan Sosič: Pripovedovalec in fokalizacija Glavna in odgovorna urednica Editor: Darja Pavlič Mária Bátorová: Slovaška književnost in kultura s »postkolonialnega« Uredniški odbor Editorial Board: vidika Darko Dolinar, Marijan Dović, Marko Juvan, Vanesa Matajc, Lado Kralj, Vid Snoj, Jola Škulj Janko Trupej: Prevajanje rasističnega diskurza o temnopoltih v slovenščino Uredniški svet Advisory Board: Vladimir Biti (Dunaj/Wien), Janko Kos, Aleksander Skaza, Neva Šlibar, Galin Tihanov TEMATSKI SKLOP (London), Ivan Verč (Trst/Trieste), Tomo Virk, Peter V. Zima (Celovec/Klagenfurt) Willie van Peer: Teorije književnosti: metarefleksija in rešitev © avtorji © Authors Špela Virant: Zrcalo življenja ali njegov vzor: o realizmu v 20. stoletju PKn izhaja trikrat na leto PKn is published three times a year. Dejan Kos: Univerzalnost literature v epistemološki perspektivi Prispevke in naročila pošiljajte na naslov Send manuscripts and orders to: Revija Primerjalna književnost, FF, Aškerčeva 2, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia. Mihaela Ursa: Univerzalnost kot stalnica v primerjalni književnosti: v Letna naročnina: 17,50 €, za študente in dijake 8,80 €. smeri celostne teorije kulturnih stikov TR 02010-0016827526, z oznako »za revijo«. Cena posamezne številke: 6,30 €. Michelle Gadpaille: Tematika in njene posledice: razmišljanje o knjigi Annual subscription/single issues (outside Slovenia): € 35/€ 12.60. -

4* 1) I > K E Back the Nigtvtl

FREEDOM AND FAIRNESS att 3Fmnzmm Jfag VOL.105 ISSUE 11 FOGHORN.USFCA.EDU SEPTEMBER 3, 2009 Gender, Sexuality and Women's Resource Center Opens New center is a safe space for all LAURA PLANTHOLT also a wealth of information compiled by StaffWriter graduate students in the School of Nurs In one of the most heavily-trafficked ing advising young people what to do if parts of USF campus, next to the Market they are in an abusive relationship or have Cafe in the University Center, the new been sexually assaulted. Gender, Sexuality and Women's Resource Graduate nursing students are the staff Center (GSWRC) has opened its doors. that keeps the GSWRC going. Joellyn The resource center is the brainchild of Morris, one such staff member who has a group of students and administrators been working in the center since June, said ro in response to several incidents of sexual the center can help people establish healthy relationships, can educate people how to News you can use: Find violence reported last semester (for more prevent sexual assault, and can provide out who's tweeting at USF. information see "Caskey" on page 3). Senior Samantha Sheppard-Gonzales support for survivors of sexual assault. Most importantly, she said, "It is nice NEWS saw the center take shape from the begin —PAGE __ ning as the co-director of the club Stu to see a safe space on campus for women, dents Taking Action Against Sexual Vio and for the LGBTQJlesbian, gay, bisexu lence (STAASV) ' al, transgender and questioning) commu- •__ " When these concerned students started nity. -

Extensions of Remarks 16843 Extensions of Remarks

June 25, 1980 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 16843 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS KEYNOTE SPEECH OF CHARLES lungs, free of braces and free of crippling function; it represents one of the most L. MASSEY, PRESIDENT, THE in one-tenth the time required to wipe out exhilarating challenges to be met in the last MARCH OF DIMES BIRTH DE smallpox-is testimony to our people's con decades of this century. FECTS FOUNDATION scious investment of themselves to insure That's because we give the word "healing" their children's future health. a special definition with extra dimensions. And it is true to this unique heritage that Not just treating and curing birth defects in HON. RICHARD L. OTTINGER March of Dimes volunteers are still laboring the present tense, but preventing birth de OF NEW YORK not for their own health but for the health fects in the future tense. And not just con of future generations. Tomorrow and the cern for the human body and its organs, but IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES following days, physicians and scientists, concern for individual human beings in the Wednesday, June 25, 1980 nurses and nutritionists, educators and lay total context of their environment. persons sitting among you tonight will star The Greek physician, Hippocrates-the e Mr. OTTINGER. Mr. Speaker, I in a multi-media production, playing the father of medicine-said that "healing is a would like to bring to the attention of role of themselves as they demonstrate the matter of time but it sometimes is also a my colleagues the speech given earlier forces they have fashioned in pursuing the matter of opportunity." this month by Charles L.