External Projection of the Basque Language and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unaided Awareness of Language & Cultural Centers

Awareness, Attitudes & Usage Study 2018 Baseline Wave Étude sur la Notoriété de la Marque: L’Alliance Française de Chicago. - 1 Background information Last year’s presentation: ❑ Summarized about 4 years of research: ◆ Student satisfaction surveys. ◆ Focus groups: web site & brochure. ◆ Simmons data: activity profiles for target consumers. ◆ Student engagement survey. ❑ Results: ◆ New, smaller brochure ◆ New, responsive website ◆ Advertising on public transportation (CTA Red Line) ◆ Advertising on the building ◆ Importance of cell phones! - 2 Where we are today: The new responsive AF-Chicago website AF-Chicago 2018 Marketing Program 22-Jan-18 - 3 This year… AA&U Study - measures: ❑ Brand awareness. ❑ Attitudes about the brand. ❑ Usage (patronage). Purpose: ❑ Assess effectiveness of marketing campaign (over time)… ❑ Increase brand awareness? ❑ Improve attitudes & usage? Frequency: ❑ Usually once a year; ❑ More often if there is a major expenditure in marketing. - 4 Survey sample characteristics Our sample composition: ❑ 999 respondents ❑ Residents of “Greater Chicago Metro Area” ◆ Counties immediately surrounding Chicago & Cook County. ◆ Including Lake & Porter in NW Indiana. ◆ Excluding Lake and Gundy in IL. ❑ Roughly even balance of men and women. ❑ Age range: 25-75. ❑ Education: HS Diploma + ❑ Income: $50k+ annual HHI. - 5 Why the large sample? 999 Respondents… ❑ We anticipated that our target group would be small. ❑ Need a large sample to find them in sufficient numbers to obtain reliable descriptive statistics. - 6 Brand Awareness – Notoriété de la Marque • Unaided Brand Awareness • Aided Brand Awareness - 7 Why is “unaided brand awareness” important? Direct correlation with market dominance ❑ “Unaided brand awareness” is the key predictor of market dominance. ❑ The top three brands in almost any category are those that are recalled immediately and spontaneously by the members of the target audience. -

“Proyecto Conectados Y Seguros”: Una Nueva Línea De Trabajo En La RBIC

IX JORNADA PROFESIONAL DE LA RED DE BIBLIOTECAS DEL INSTITUTO CERVANTES: Bibliotecas y empoderamiento digital. MADRID, 14 de diciembre 2016 “Proyecto Conectados y seguros”: una nueva línea de trabajo en la RBIC. Ana Roca Gadea1 (Instituto Cervantes) Spanish abstract Consideradas por los ciudadanos como lugares seguros y confiables, las bibliotecas no cesan de ampliar el rol que desempeñan en el seno de sus comunidades. Fomentar el empoderamiento digital (la capacidad de utilizar la tecnología para introducir cambios positivos en las vidas de personas y colectivos) se ha convertido en un aspecto central dentro de la labor de las bibliotecas de apoyar la educación a lo largo de la vida. La biblioteca del Instituto Cervantes de Atenas organizó entre 2013 y 2016 algunas iniciativas de capacitación digital, entre ellas, el Proyecto Conectados y Seguros, en colaboración con la Fundación Cibervoluntarios. La Red de Bibliotecas Cervantes se enfrenta actualmente al reto de integrar esta línea de trabajo en el seno de su principal ámbito de actuación, esto es, con la difusión de la lengua y la cultura de los países de habla española. English abstratc Considered by citizens as trusted and safe places, libraries are continuously widening their role within their communities. Promoting digital empowerment (the capacity of using technology to introduce positive changes in the lives of individuals and groups) has become a key aspect in libraries’ role in supporting life-long learning. Between 2013 and 2016, the Instituto Cervantes Library in Athens organized several digital training iniciatives, such as “Safe and Connected Project”, in collaboration with Cibervoluntarios Foundation. Nowadays the Network of Instituto Cervantes Libraries faces the challenge of integrating this line of work within its main course of action, that is the promotion of the language and culture of Spanish speaking countries. -

External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish

東京外国語大学論集 第 100 号(2020) TOKYO UNIVERSITY OF FOREIGN STUDIES, AREA AND CULTURE STUDIES 100 (2020) 43 External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish 「少数言語」の対外普及 ̶̶ バスク語とカタルーニャ語 の事例をスペイン語の事例と比較しつつ HAGIO Sho W o r l d L a n g u a g e a n d S o c i e t y E d u c a t i o n C e n t r e , T o k y o U n i v e r s i t y o f F o r e i g n S t u d i e s 萩尾 生 東京外国語大学 世界言語社会教育センター 1. The Historical Background of Language Dissemina on Overseas 2. Theore cal Frameworks 2.1. Implemen ng the Basis of External Diff usion 2.2. Demarca on of “Internal” and “External” 2.3. The Mo ves and Aims of External Projec on of a Language 3. The Case of Spain 3.1. The Overall View of Language Policy in Spain 3.2. The Cervantes Ins tute 3.3. The Ramon Llull Ins tute 3.4. The Etxepare Basque Ins tute 4. Transforma on of Discourse 4.1. The Ra onale for External Projec on and Added Value 4.2. Toward Deterritorializa on and Individualiza on? 5. Hypothe cal Conclusion Keywords: Language spread, language dissemination abroad, minority language, Basque, Catalan, Spanish, linguistic value, linguistic market キーワード:言語普及、言語の対外普及、少数言語、バスク語、カタルーニャ語、スペイン語、言語価値、 言語市場 ᮏ✏䛾ⴭసᶒ䛿ⴭ⪅䛜ᡤᣢ䛧䚸 䜽䝸䜶䜲䝔䜱䝤䞉 䝁䝰䞁䝈⾲♧㻠㻚㻜ᅜ㝿䝷䜲䝉䞁䝇䠄㻯㻯㻙㻮㼅㻕ୗ䛻ᥦ౪䛧䜎䛩䚹 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 萩尾 生 Hagio Sho External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish 「少数言語」 の対外普及 —— バスク語とカタルーニャ語 の 事 例をスペイン語の事例と比較しつつ 44 Abstract This paper explores the value of the external projection of a minority language overseas, taking into account the cases of Basque and Catalan in comparison with Spanish. -

11, Avenue Marceau 75116 Paris Tél. 01 47 20 70 79

LIENS INTERNET Visite nuestra página en Internet / Visitez notre site web : www.paris.cervantes.es Acceda al catálogo en línea y a Mi biblioteca / Accédez à notre catalogue en ligne et à la rubrique Mi biblioteca : http://absysnet.cervantes.es/abnetopac02/abnetcl. exe?SUBC=PARI Participe en nuestro blog / Participez à notre blog : http://biblioteca-paris.blogs.cervantes.es/ HORAIRES Lundi et jeudi de 14h00 à 19h00 Mardi, mercredi et vendredi de 11h00 à 17h00 11, Avenue Marceau [email protected] 75116 Paris http://biblioteca-paris.blogs.cervantes.es/ Tél. 01 47 20 70 79 Fax 01 47 20 27 49 www.paris.cervantes.es Biblioteca Octavio Paz Bibliothèque Octavio Paz La Biblioteca Octavio Paz, situada en el centro de París, alberga una La Bibliothèque Octavio Paz, située en centre-ville, propose une collection colección especializada en España e Hispanoamérica de más de 60.000 spécialisée d’environ 60.000 volumes (livres, périodiques, films et documentos (libros, publicaciones periódicas, películas y documentales documentaires en DVD, audiolivres et livres électroniques, musique sur en DVD, audiolibros, libros electrónicos, música en CD, etc.). Desde el CD, etc.). Le catalogue disponible sur Internet permet la consultation des catálogo en Internet se pueden consultar los fondos, renovar préstamos, fonds ainsi que le renouvellement des prêts, la réservation des articles et hacer reservas y descargar audiolibros y libros electrónicos. le téléchargement de livres audio et électroniques. SERVICIOS SERVICES . Consulta y préstamo (presencial y en línea) . Consultation et prêt (présentiel et en ligne) . Información bibliográfica . Informations bibliographiques . Servicio de documentación . Service de documentation . Préstamo interbibliotecario y obtención de documentos . -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

Linguae Vasconum Primitiae

LINGUAE VASCONUM PRIMITIAE 1545-1995 Liburu hau Euskaltzaindiak argitaratua da, ondoko erakundeen lankidetza eta laguntzari esker: Este libro ha sido publicado por Euskaltzaindia, Real Academia de la Len gua Vasca, gracias a la colaboración y subvención de las siguientes entidades: Gobierno de Navarra / Nafarroako Gobernua Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea Universidad de Deusto / Deustuko Unibertsitatea Universidad Pública de Navarra / Nafarroako Unibertsitate Publikoa Traductores: Patxi Altuna (Prólogo y Texto) Xabier Kintana (Presentación) Translator: Mikel Morris Pagoeta (Prefaces and text) Traducteurs: René Lafon (Texte) Piarres Charritton (Prologue) Übersetzer: Johannes Kabatek (Text) Ludger Mees (Vorwort und Einleitung) Traduttore: Danilo Manera (Prologhi e testo) Koordinatzailea / Coordinador: Xabier Kintana Azala eta irudiak / Portada e ilustraciones: Fernando García Angulo Argazkiak / Fotografías: Teresa Lekunberri eta Xabier Kintana © Euskaltzaindia Plaza Barria, 15. 48005 BIl.Bü ISBN: 84-85479-78-5 l.egezko Gordailua: BI-2728-95 Fotokonposaketa: IKUR, S.A. Cuevas de Ekain, 3, 1" - 48005 BIl.BAO Inprirnatzailea: RüNTEGl, SAL Grafikagintza Avda. Ribera de Erandio, 5 . 48950 ERANDlO (Bizkaia) LINGUAE VASCONUM PRIMITIAE Bemard Etxepare REAL ACADEMIA DE LA LENGUA VASCA EUSKALTZAINDIA Aurkibidea / Indice / Index / Index / Inhalt / Indice Euskara Aurkezpena . 11 Hitzaurrea 13 Faksimilea 19 Testua .. 77 Español Presentación.............................. 125 Prólogo 127 Texto 135 English Foreword . 181 Preface . 183 Text . 191 Francais Avant-propos ...... 239 Préface .. ... 241 Remarques . 249 Texte . 251 Deutsch Vorwort . 299 Einleitung 301 Text ..... 309 Italiano Presentazione 357 Prologo . 359 Testo . 367 7 LINGUAE VASCONUM PRIMITIAE Euskaldunen hizkuntzaren hasikinak Lehen euskal liburu inprimatua 1545 AURKEZPENA Lau mende eta erdi iragan dira. Etxepareren orduko ametsa: euskara «scriba dayteien lengoage bat», hots, ahozko mintzairatik igan dadin min tzaira idatzira, «nola berce oroc baitute scribatzen bervan». -

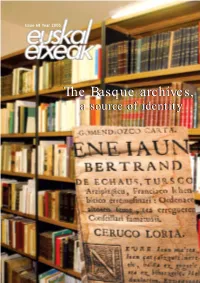

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

Become a Member

Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo New and Renewal Application for Calendar Year 2021 The Dante Alighieri Society was formed in Italy in July 1889 to “promote the study of the Italian language and culture throughout the world…independent of political ideologies, national, or ethnic origin or religious beliefs. The Society is the free association of people -not just Italians- but all people everywhere who are united by their love for the Italian language and culture and the spirit of universal humanism that these represent.” The Society was named after Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), a pre-Renaissance poet from Florence, Italy. Dante, the author of The Divine Comedy, is considered the father of the Italian language. The Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo, Colorado was founded by Father Christopher Tomatis on October 24, 1977 and ratified by the Dante Alighieri Society in Rome, Italy on December 3, 1977. Mission Statement The mission of the Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo, Colorado is to promote and preserve the Italian language, culture, and customs in Pueblo and the Southern Colorado Region. ° Scholarships will be awarded to selected senior high students who have completed two or more years of Italian language classes in the Pueblo area high schools. ° Cultural and social activities will be sponsored to enhance the Italian-American community. Activities of the Society Cultural Dinner Meetings Regional Italian Dinner (November) Carnevale Dinner Dance (February) Annual Christmas Party (December) Scholarship Awards (May) Artistic Performances and Speakers Dante Summer Festa (August) Sister City Festival Participation Italian Conversation Classes Italian Language Scholarships To join the Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo or to renew your membership, please detach and mail with your check. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

10 Places in Manila to Learn a Foreign Language | SPOT.Ph

5.1.2018 10 Places In Manila To Learn A Foreign Language | SPOT.ph Eat + Drink News + Features Arts + Culture Entertainment Things to Do Shopping + Services Win Win Yum ENTERTAINMENT SHOPPING + SERVICES EAT + DRINK EAT + DRINK CREATED WITH SAN MIG LIGHT 10 New Songs to Add Top 10 Nail Salons in The Alley by Vikings Top 10 Blueberry 5 New Year's to Your Playlist This Manila (2018 Edition) Is the Buet You Cheesecakes in Resolutions For January Didn't Know You Manila Young Employees Needed Things To Do What's New Win 10 Places in Manila to Learn a Foreign Language For when you want to say bonjour, hola, arigato and more. by Rian Mendiola Feb 24, 2016 6K Shares Share Tweet Pin 21 Comments Save to Facebook Like You and 907K others like this. Share Pinoy Noche Buenas Wouldn’t Be Complete Without These Dishes What would Christmas be without these? MOST POPULAR (SPOT.ph) Knowing a language other than your own and English is a handy skill that will save you from a lot of trouble—especially when you’re traveling abroad. But even if you aren’t, there’s Expand nothing wrong with learning a foreign language; aer all, knowing one—or two—can teach you EAT + DRINK https://www.spot.ph/things-to-do/the-latest-things-to-do/65300/10-places-in-manila-to-learn-a-foreign-language 1/9 5.1.2018 10 Places In Manila To Learn A Foreign Language | SPOT.ph so much about dierent cultures. If you want to get schooled, there are plenty of places in 10 Places in Manila With the Best Views Eat + Drink News + Features Arts + Culture Entertainment Things to Do Shopping + Services Manila to suit a range of learning styles, schedules, and budgets. -

Landmark 5Th Edition of PHOTOFAIRS | Shanghai Opens

th Landmark 5 edition of PHOTOFAIRS | Shanghai opens today Shanghai, September 20, 2018: Building upon its success over the last five years, PHOTOFAIRS | Shanghai opens today at the Shanghai Exhibition Center. It runs until Sunday 23 September with Presenting Partner Porsche. As Asia Pacific’s leading destination for discovering and collecting photography, PHOTOFAIRS | Shanghai offers unique access to some of China, Korea, Japan, Europe and North America’s most compelling artists through its highly curated gallery presentations and a critically acclaimed five-part public program. With the growing global confidence in the Chinese art market and wider Asia Pacific collector base, the Fair delivers a vital platform for galleries from across the region to be seen internationally, and for galleries from around the world to enter the Chinese market. PHOTOFAIRS | Shanghai is celebrated for its focus on progressive artwork and supports galleries pushing the boundaries of photography. The 2018 edition features 55 leading dealers from 15 countries and 27 cities, with 80% hailing from Asia Pacific. Alongside classic masterpieces, visitors will enjoy contemporary photography in all its forms; large-scale installations, moving image and new technologies from more than 150 Chinese and international artists. The Fair is supported by Shanghai’s leading museums including the Fosun Foundation, HOW Museum, OCAT Shanghai, Yuz Museum and Shanghai Centre for Photography, each presenting significant exhibitions dedicated to artists working in photography, making this week in September a landmark event within the cultural calendar. Georgia Griffiths, PHOTOFAIRS Group Fair Director, comments: “I am really looking forward to the 5th edition of PHOTOFAIRS | Shanghai. A fair is made by its galleries and the list this year is stronger than ever – from galleries who have been with the Fair since its launch in 2014 through to today’s most exciting new programmes in China, Asia Pacific and across the world. -

The Institutionalization of Basque Literature, Or the Long Way to the World Republic of Letters*

Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis literaris. Vol. XVIII (2013) 163-170 THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF BASQUE LITERATURE, OR THE LONG WAY TO THE WORLD REPUBLIC OF LETTERS* Mari Jose Olaziregi University of the Basque Country-Etxepare Basque Institute 1. BASQUE LITERATURE Before going on, we would like to point out that when talking about Basque Literature we are referring to the literature written in Basque. This differentiation deserves clarification since literature written in the Basque language has not provided – neither has the language that supports it, Euskara – the exclusive and complete literary expression of Basque reality. As Jesús María Lasagabaster rightly notes (Lasagabaster 2002), as well as the literature written in Basque there is Basque literature written in both Spanish and French, identifiable by the Basque origin of the authors who wrote it, by their subjects, and even by the presence of a singular worldview that may be said to be Basque. This is why Lasagabaster talks about “the literatures of the Basques”, and although it is true that, from a comparative point of view, most literatures are compared in terms of the language in which they are expressed rather than in terms of the author’s nationality (Guillén, 1998), the truth is that only recently has Basque literary historiography opted for a post-national approach, i.e. an approach that takes into account literature written by Basques in their various languages (Gabilondo, 2006). The question is whether such an approach, appealing as it would be in terms of overcoming the inertia in Basque literary historiography, may lead to a historiographical approach that actually exceeds the limits established by each of the Basque literary systems (the Basque, Spanish and French ones, for example).