Catharine Mckenty Foreword by Alan Hustak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 26, 1978

elArmrding-to lrwing Music for free. Both the Concordia Orchestra and the Concordia Chamber Layton Ensemble begin their seasons of free concerts this week. By Beverley Smith Dates· and progra'ms on page Concordia students will be glad to 2. know not o_nly that Irving Layton is Concordia in brief. back in town, but that he'll be teaching A quick look at interesting a course at Sir George Williams in Creative Writing. things Concordia people and Canada's foremost erotic poet has departments are doing can be left Toronto "the good" for good and found in At A Glance. This taken up residence once again in his native city of Montreal. What are the week on page 3. reasons behind his sudden shift of Scholarship pays off. allegiance and residence? In part, Layton claims that he never A complete list of the winners really did leave the town of his birth. of the 1978 graduate students He always maintained an affectionate awards and a look at some of regard for the Montreal of his their projects can be f~und on childhood. But the materialism and lack of warmth of the Queen City also page 4. played a part. To Layton, Toronto And they' re off! symbolized a cultural wasteland, a The race between the place where fortunes were made at the expense of meaningful human contact. Municipal Action Group and But Layton is not the type of poet, the Montreal Citizens' either, to elect to remain very far Movement for the hearts and removed from centres of cultural or votes of Montrealers has political controversy. -

Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy

Dr. Francesco Gallo OUTSTANDING FAMILIES of Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy from the XVI to the XX centuries EMIGRATION to USA and Canada from 1880 to 1930 Padua, Italy August 2014 1 Photo on front cover: Graphic drawing of Aiello of the XVII century by Pietro Angius 2014, an readaptation of Giovan Battista Pacichelli's drawing of 1693 (see page 6) Photo on page 1: Oil painting of Aiello Calabro by Rosario Bernardo (1993) Photo on back cover: George Benjamin Luks, In the Steerage, 1900 Oil on canvas 77.8 x 48.9 cm North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Purchased with funds from the Elizabeth Gibson Taylor and Walter Frank Taylor Fund and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.12 2 With deep felt gratitude and humility I dedicate this publication to Prof. Rocco Liberti a pioneer in studying Aiello's local history and author of the books: "Ajello Calabro: note storiche " published in 1969 and "Storia dello Stato di Aiello in Calabria " published in 1978 The author is Francesco Gallo, a Medical Doctor, a Psychiatrist, a Professor at the University of Maryland (European Division) and a local history researcher. He is a member of various historical societies: Historical Association of Calabria, Academy of Cosenza and Historic Salida Inc. 3 Coat of arms of some Aiellese noble families (from the book by Cesare Orlandi (1734-1779): "Delle città d'Italia e sue isole adjacenti compendiose notizie", Printer "Augusta" in Perugia, 1770) 4 SUMMARY of the book Introduction 7 Presentation 9 Brief History of the town of Aiello Calabro -

Christian History & Biography

Issue 98: Christianity in China As for Me and My House The house-church movement survived persecution and created a surge of Christian growth across China. Tony Lambert On the eve of the Communist victory in 1949, there were around one million Protestants (of all denominations) in China. In 2007, even the most conservative official polls reported 40 million, and these do not take into account the millions of secret Christians in the Communist Party and the government. What accounts for this astounding growth? Many observers point to the role of Chinese house churches. The house-church movement began in the pre-1949 missionary era. New converts—especially in evangelical missions like the China Inland Mission and the Christian & Missionary Alliance—would often meet in homes. Also, the rapidly growing independent churches, such as the True Jesus Church, the Little Flock, and the Jesus Family, stressed lay ministry and evangelism. The Little Flock had no pastors, relying on every "brother" to lead ministry, and attracted many educated city people and students who were dissatisfied with the traditional foreign missions and denominations. The Jesus Family practiced communal living and attracted the rural poor. These independent churches were uniquely placed to survive, and eventually flourish, in the new, strictly-controlled environment. In the early 1950s, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement eliminated denominations and created a stifling political control over the dwindling churches. Many believers quietly began to pull out of this system. -

This Is a Complete Transcript of the Oral History Interview with Mary Goforth Moynan (CN 189, T3) for the Billy Graham Center Archives

This is a complete transcript of the oral history interview with Mary Goforth Moynan (CN 189, T3) for the Billy Graham Center Archives. No spoken words which were recorded are omitted. In a very few cases, the transcribers could not understand what was said, in which case [unclear] was inserted. Also, grunts and verbal hesitations such as “ah” or “um” are usually omitted. Readers of this transcript should remember that this is a transcript of spoken English, which follows a different rhythm and even rule than written English. Three dots indicate an interruption or break in the train of thought within the sentence of the speaker. Four dots indicate what the transcriber believes to be the end of an incomplete sentence. ( ) Word in parentheses are asides made by the speaker. [ ] Words in brackets are comments made by the transcriber. This transcript was created by Kate Baisley, Janyce H. Nasgowitz, and Paul Ericksen and was completed in April 2000. Please note: This oral history interview expresses the personal memories and opinions of the interviewee and does not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Billy Graham Center Archives or Wheaton College. © 2017. The Billy Graham Center Archives. All rights reserved. This transcript may be reused with the following publication credit: Used by permission of the Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL. BGC Archives CN 189, T3 Transcript - Page 2 Collection 189, T3. Oral history interview with Mary Goforth Moynan by Robert Van Gorder (and for a later portion of the recording by an unidentified woman, perhaps Van Gorder=s wife), recorded between March and June 1980. -

Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé Annika Barrett Whitworth University

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University History of Christianity II: TH 314 Honors Program 5-2017 Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé Annika Barrett Whitworth University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/th314h Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Barrett, Annika , "Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé" Whitworth University (2017). History of Christianity II: TH 314. Paper 16. https://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/th314h/16 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Christianity II: TH 314 by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. Annika Barrett The Story of Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé What is it about the monastic community in Taizé, France that has inspired international admira- tion, especially among young people? Don’t most people today think of monasteries as archaic and dull, a place for religious extremists who were una- ble to marry? Yet, since its birth in the mid 1900s, Brother Roger at a prayer in Taizé. Taizé has drawn hundreds of thousands of young Photo credit: João Pedro Gonçalves adult pilgrims from all around the world, influenced worship practices on an international scale, and welcomed spiritual giants from Protestant, Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox backgrounds. Un- like traditional monastic orders, Taizé is made up of an ecumenical brotherhood that lives in dy- namic adaptability, practicing hospitality for culturally diverse believers while remaining rooted in the gospel. -

Montreal, Quebec May 31, 1976 Volume 62

MACKENZIE VALLEY PIPELINE INQUIRY IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATIONS BY EACH OF (a) CANADIAN ARCTIC GAS PIPELINE LIMITED FOR A RIGHT-OF-WAY THAT MIGHT BE GRANTED ACROSS CROWN LANDS WITHIN THE YUKON TERRITORY AND THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES, and (b) FOOTHILLS PIPE LINES LTD. FOR A RIGHT-OF-WAY THAT MIGHT BE GRANTED ACROSS CROWN LANDS WITHIN THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES FOR THE PURPOSE OF A PROPOSED MACKENZIE VALLEY PIPELINE and IN THE MATTER OF THE SOCIAL, ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACT REGIONALLY OF THE CONSTRUCTION, OPERATION AND SUBSEQUENT ABANDONMENT OF THE ABOVE PROPOSED PIPELINE (Before the Honourable Mr. Justice Berger, Commissioner) Montreal, Quebec May 31, 1976 PROCEEDINGS AT COMMUNITY HEARING Volume 62 The 2003 electronic version prepared from the original transcripts by Allwest Reporting Ltd. Vancouver, B.C. V6B 3A7 Canada Ph: 604-683-4774 Fax: 604-683-9378 www.allwestbc.com APPEARANCES Mr. Ian G. Scott, Q.C. Mr. Ian Waddell, and Mr. Ian Roland for Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry Mr. Pierre Genest, Q.C. and Mr. Darryl Carter, for Canadian Arctic Gas Pipeline Lim- ited; Mr. Alan Hollingworth and Mr. John W. Lutes for Foothills Pipe- lines Ltd.; Mr. Russell Anthony and pro. Alastair Lucas for Canadian Arctic Resources Committee Mr. Glen Bell, for Northwest Territo- ries Indian Brotherhood, and Metis Association of the Northwest Territories. INDEX Page WITNESSES: Guy POIRIER 6883 John CIACCIA 6889 Pierre MORIN 6907 Chief Andrew DELISLE 6911 Jean-Paul PERRAS 6920 Rick PONTING 6931 John FRANKLIN 6947 EXHIBITS: C-509 Province of Quebec Chamber of Commerce - G. Poirier 6888 C-510 Submission by J. -

December 2009 the SENIOR TIMES Validation: a Special Understanding Photo: Susan Gold the Alzheimer Groupe Team Kristine Berey Rubin Says

Help Generations help kids generationsfoundation.com O 514-933-8585 DECEMBER2009 www.theseniortimes.com VOL.XXIV N 3 Share The Warmth this holiday season FOR THE CHILDREN Kensington Knitters knit for Dans la rue Westhill grandmothers knit and Montreal Children’s Hospital p. 21 for African children p. 32 Editorial DELUXE BUS TOUR NEW YEAR’S EVE Tory attack flyers backfire GALA Conservative MPs have upset many Montrealers Royal MP Irwin Cotler has denounced as “close to Thursday, Dec 31 pm departure with their scurrilous attack ads, mailed to peo- hate speech.”The pamphlet accuses the Liberals of Rideau Carleton/Raceway Slots (Ottawa) ple with Jewish-sounding names in ridings with “willingly participating in the overly anti-Semitic significant numbers of Jewish voters. Durban I – the human rights conference in South Dance the Night Away • Eat, Drink & be Merry Live Entertainment • Great Buffet There is much that is abhorrent about the tactic Africa that Cotler attended in 2001 along with a Casino Bonus • Free Trip Giveaway itself and the content. Many of those who received Canadian delegations. In fact, Cotler, along with Weekly, Sat/Sun Departures the flyer are furious that the Conservatives as- Israeli government encouragement, showed sume, falsely, that Canadian Jews base their vote courage and leadership by staying on, along with CALL CLAIRE 514-979-6277 on support for Israel, over and above the commu- representatives of major Jewish organizations, in nity members’ long-standing preoccupation with an effort to combat and bear witness to what Lois Hardacker social justice, health care, the environment and a turned into an anti-Israel and anti-Semitic hate Royal LePage Action Chartered Broker host of other issues. -

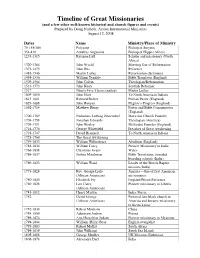

Timeline of Great Missionaries

Timeline of Great Missionaries (and a few other well-known historical and church figures and events) Prepared by Doug Nichols, Action International Ministries August 12, 2008 Dates Name Ministry/Place of Ministry 70-155/160 Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna 354-430 Aurelius Augustine Bishop of Hippo (Africa) 1235-1315 Raymon Lull Scholar and missionary (North Africa) 1320-1384 John Wyclif Morning Star of Reformation 1373-1475 John Hus Reformer 1483-1546 Martin Luther Reformation (Germany) 1494-1536 William Tyndale Bible Translator (England) 1509-1564 John Calvin Theologian/Reformation 1513-1573 John Knox Scottish Reformer 1517 Ninety-Five Theses (nailed) Martin Luther 1605-1690 John Eliot To North American Indians 1615-1691 Richard Baxter Puritan Pastor (England) 1628-1688 John Bunyan Pilgrim’s Progress (England) 1662-1714 Matthew Henry Pastor and Bible Commentator (England) 1700-1769 Nicholaus Ludwig Zinzendorf Moravian Church Founder 1703-1758 Jonathan Edwards Theologian (America) 1703-1791 John Wesley Methodist Founder (England) 1714-1770 George Whitefield Preacher of Great Awakening 1718-1747 David Brainerd To North American Indians 1725-1760 The Great Awakening 1759-1833 William Wilberforce Abolition (England) 1761-1834 William Carey Pioneer Missionary to India 1766-1838 Christmas Evans Wales 1768-1837 Joshua Marshman Bible Translation, founded boarding schools (India) 1769-1823 William Ward Leader of the British Baptist mission (India) 1773-1828 Rev. George Liele Jamaica – One of first American (African American) missionaries 1780-1845 -

Reaching for the Top: a Report by The

REACHING FOR THE TOP A Report by the Advisor on Healthy Children & Youth Dr. K. Kellie Leitch The views expressed in this Report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Canada. Published by authority of the Minister of Health. Reaching for the Top: A Report by the Advisor on Healthy Children & Youth is available on Internet at the following address: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre : Vers de nouveaux sommets : rapport de la conseillère en santé des enfants et des jeunes For further information or to obtain additional copies, please contact: Publications Health Canada Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K9 Tel.: 613-954-5995 Fax: 613-941-5366 E-Mail: [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Health Canada, 2007 HC Pub.: 4552 Print Cat.: H21-296/2007E ISBN: 978-0-662-46455-6 PDF Cat.: H21-296/2007E-PDF ISBN: 978-0-662-46456-3 REACHING FOR THE TOP A Report by the Advisor on Healthy Children & Youth Dr. K. Kellie Leitch K. Kellie Leitch MD, MBA, FRCS (C) Chair/Chief, Division of Paediatric Surgery Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon Email: [email protected] Tel: 519.685.8500 ext 52132 Fax: 519.685.8038 Room E2-620D Minister: As Canadians, we are very fortunate in so many ways. We have tremendous opportunities to reach our full potential in a free, welcoming, and ambitious country. For those of us who were born in this country, it has often been said that we are among the luckiest people in the world. -

Twenty Or So Years Ago, I Had the Great Privilege of Being at a Mass in St Peter’S Rome Celebrated by Pope St John Paul II

Twenty or so years ago, I had the great privilege of being at a mass in St Peter’s Rome celebrated by Pope St John Paul II. Also present on that occasion was the Protestant Brother Roger Schutz, the founder and then prior of the ecumenical monastic community of Taizé. Both now well on in years and ailing in different ways, Pope John Paul and Brother Roger had a well known friendship and it was touching to see the Pope personally give communion to his Protestant friend. This year, the Common Worship feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, known by most Christians as her Assumption, the Dormition or the Falling Asleep, is also the eve of the fifteenth anniversary of Roger’s horrific, and equally public, murder in his own monastic church, within six months of the death of John Paul himself. I want to suggest three themes that were characteristic both of Mary and Brother Roger and also offer us a sure pathway for our own discipleship: joy, simplicity and mercy. I was led to these by an interview on TV many years ago with Br Alois, Brother Roger’s successor as prior of Taizé, who described how they were at the heart of Brother Roger’s approach to life and guidance of his community. He had written them into the Rule of Taizé, and saw them as a kind of summary of the Beatitudes: [3] "Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. [4] "Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. -

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) Electronic Version Obtained from Table of Contents

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) Electronic Version obtained from http://www.gcc.ca/ Table of Contents Section Page Map of Territory..........................................................................................................................1 Philosophy of the Agreement...................................................................................................2 Section 1 : Definitions................................................................................................................13 Section 2 : Principal Provisions................................................................................................16 Section 3 : Eligibility ..................................................................................................................22 Section 4 : Preliminary Territorial Description.....................................................................40 Section 5 : Land Regime.............................................................................................................55 Section 6 : Land Selection - Inuit of Quebec,.........................................................................69 Section 7 : Land Regime Applicable to the Inuit..................................................................73 Section 8 : Technical Aspects....................................................................................................86 Section 9 : Local Government over Category IA Lands.......................................................121 Section 10 : Cree -

Next- Generation University President’S Report 2019

NEXT- GENERATION UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2019 CREATIVE. URBAN. BOLD. ENGAGED. BOLDLY ADVANCING 2 NEXT-GEN EDUCATION This 2019 President’s Report tries to capture some of the incredible progress our community has made over the past year. You will read about successes that signal our place as one of Quebec and Canada’s major universities. As I near the end of my mandate as Concordia’s president, I am proud of our achievements and excited about the university’s future. We have really come into our own. 3 Enjoy the read! Alan Shepard MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT FROM MESSAGE President ABOUT CONCORDIA oncordia University, located in the vibrant and multicultural city of Montreal, is among the top-ranked C universities worldwide founded within the last 50 years and among the largest urban universities in Canada. Concordia prepares more than 50,000 students for a world of challenges and opportunities. As a next-generation university, Concordia strives to be forward-looking, agile and responsive, while remaining deeply rooted in the community and globally networked. Our nine strategic directions exemplify a bold, daring, innovative and transformative approach to university education and research. Our more than 2,300 faculty and researchers collaborate with other thinkers, Montreal-based companies and international organizations. concordia.ca/about CONCORDIA AT A GLANCE* 11th largest university in Canada, 83% of final-year undergraduate students fourth largest in Quebec satisfied or very satisfied with the overall quality of their Concordia