Van Gogh Museum Journal 1997-1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 10:23:11PM Via Free Access Notes to Chapter 1 671

Notes 1 Introduction. Fall and Redemption: The Divine Artist 1 Émile Verhaeren, “La place de James Ensor Michelangelo, 3: 1386–98; Summers, Michelangelo dans l’art contemporain,” in Verhaeren, James and the Language of Art, 238–39. Ensor, 98: “À toutes les périodes de l’histoire, 11 Sulzberger, “Les modèles italiens,” 257–64. ces influences de peuple à peuple et d’école à 12 Siena, Church of the Carmines, oil on panel, école se sont produites. Jadis l’Italie dominait 348 × 225 cm; Sanminiatelli, Domenico profondément les Floris, les Vaenius et les de Vos. Beccafumi, 101–02, no. 43. Tous pourtant ont trouvé place chez nous, dans 13 E.g., Bhabha, Location of Culture; Burke, Cultural notre école septentrionale. Plus tard, Pierre- Hybridity; Burke, Hybrid Renaissance; Canclini, Paul Rubens s’en fut à son tour là-bas; il revint Hybrid Cultures; Spivak, An Aesthetic Education. italianisé, mais ce fut pour renouveler tout l’art See also the overview of Mabardi, “Encounters of flamand.” a Heterogeneous Kind,” 1–20. 2 For an overview of scholarship on the painting, 14 Kim, The Traveling Artist, 48, 133–35; Payne, see the entry by Carl Van de Velde in Fabri and “Mescolare,” 273–94. Van Hout, From Quinten Metsys, 99–104, no. 3. 15 In fact, Vasari also uses the term pejoratively to The church received cathedral status in 1559, as refer to German art (opera tedesca) and to “bar- discussed in Chapter Nine. barous” art that appears to be a bad assemblage 3 Silver, The Paintings of Quinten Massys, 204–05, of components; see Payne, “Mescolare,” 290–91. -

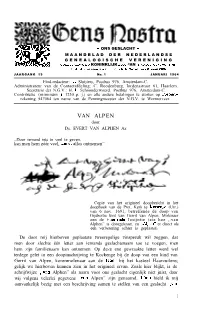

1964 Jaargang 19 (Xix)

- ONS GESLACHT - MAANDBLAD DER NEDERLANDSE GENEALOGISCHE VERENIGING OOEDGEKEURD 312 KONINKLIJK BESL. “AN 16 A”O”STUS reaa. YO. 85 Llc.tstel,jk podpeKe”rd 51, KO”i”kli,k a.,,uit van J .+r,, ,833 JAARGANG 19 No. 1 JANUARI 1964 Eind-redacteur: J. Sluijters, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Administrateur van de Contactafdeling: C. Roodenburg, Iordensstraat 61, Haarlem. Secretaris der N.G.V.: H. J. Schoonderwoerd, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Contributie (minimum f 1230 p. j.) en alle andere betalingen te storten op Postgiro- rekening 547064 ten name van de Penningmeester der N.G.V. te Wormerveer. VAN ALPEN door Ds. EVERT VAN ALPHEN Az ,,Door iemand iets te veel te geven, kan men hem zéér veel, zoniet alles ontnemen” Copie van het origineel doopbericht in het doopboek van de Prot. Kerk te Kortenge (Utr.) van 6 nov. 1691, betreffende de doop van Gijsbertie kint van Gerrit van Alpen, Molenaer aen de Haer ende Josijntie (zie hoe ,,van Alphen” is doorgekrast, en ,,Alpen” er direct als een verbetering achter is geplaatst). De door mij hierboven geplaatste tweeregelige zinspreuk wil zeggen, dat men door slechts één letter aan iemands geslachtsnaam toe te voegen, men hem zijn familienaam kan ontnemen. Op deze ene gewraakte letter werd wel terdege gelet in een doopinschrijving te Kockenge bij de doop van een kind van Gerrit van Alpen, korenmolenaar aan de Haer bij het kasteel Haarzuilens; gelijk we hierboven kunnen zien in het origineel ervan. Zoals hier blijkt, is de schrijfwijze ,,van Alphen” als naam voor ons geslacht eigenlijk niet juist, daar wij volgens velerlei gegevens ,,van Alpen” zijn genaamd. -

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

VINCENT VAN GOGH Y EL CINE Moisés BAZÁN DE HUERTA Desde

NORBA-ARTE XVII (1997) / 233-259 VINCENT VAN GOGH Y EL CINE Moisés BAZÁN DE HUERTA Desde su nacimiento, la relación del cine con las artes plásticas se ha manifes- tado en los más variados aspectos. De la influencia pictórica en el cromatismo y la configuración espacial del plano (encuadre, composición, perspectiva, profundierad), al diverso tratamiento del tiempo y los mecanismos narrativos en ambos campos; además de las bŭsquedas experimentales de las vanguardias y sus interferencias, el documental sobre arte como género, o la tradición artística como apoyo para la re- creación histórica o religiosa. También la propia pintura ha sido tratada temática- mente o como punto de partida para la reflexión sobre el proceso creativo Pero en el amplio abanico de posibilidades de esta relación, las biografías ci- nematográficas sobre artistas han sido uno de los exponentes más fructíferos, has- ta el punto de constituir casi un género propio. Dejando aparte m ŭsicos, cantantes, literatos, actores, y cifiéndonos al campo de las artes plásticas, la nómina de bio- grafiados resulta considerable: Andrei Rublev, Leonardo, Miguel Ángel, El Greco, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Velázquez, Utamaro, Fragonard, Goya, Gericault, Toulouse- Lautrec, Gauguin, Camille Claudel, Rodin, Gaudí, Pirosmani, Munch, -Carrington, Modigliani, Gaudier-Brzeska, Picasso, Dali, Goitia, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Jean Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol o Francis Bacon, entre otros, han sido objeto de re- creaciones fílmicas, aunque bastante desiguales en su calidad y planteamiento. En esta relación, como vemos, predominan las trayectorias geniales, azarosas, apasionadas y con frecuencia trágicas, es decir, las susceptibles de un desarrollo dra- mático que capte la atención y el interés del p ŭblico. -

Závěrečné Práce

JANÁČKOVA AKADEMIE MÚZICKÝCH UMĚNÍ V BRNĚ Divadelní fakulta Rozhlasová a televizní dramaturgie a scenáristika Obraz v obraze: životopisné filmy o výtvarných umělcích v současné evropské kinematografii Bakalářská práce Autor práce: Kateřina Hejnarová Vedoucí práce: doc. MgA. Hana Slavíková, Ph. D. Oponent práce: MgA. Eva Schulzová, Ph. D. Brno 2019 Bibliografický záznam HEJNAROVÁ, Kateřina. Obraz v obraze: Ņivotopisné filmy o výtvarných umělcích v současné evropské kinematografii (A Picture Inside a Picture: Biography of visual artists in contemporary European cinematography). Brno: Janáčkova akademie múzických umění v Brně, Divadelní fakulta, Ateliér rozhlasové a televizní dramaturgie a scenáristiky, 2019. Vedoucí práce: doc. MgA. Hana Slavíková, Ph.D. Anotace Tématem mé práce bude předevńím proces přenáńení poetiky výtvarného díla do filmové řeči, hledání vztahu mezi osobním ņivotem a tvorbou umělce, ale také míra a patřičnost interpretace, jíņ se reņisér ve vztahu k cizí tvorbě dopouńtí. Annotation This bachelor thesis focuses on the process of transferring the poetics of the specific artwork into the film language. It endeavours to search for the link between the personal life of the artist and his work, and also the extent and appropriateness of the director's interpretation in relation to others' lifework. Klíčová slova výtvarné umění, ņivotopis, obraz, poetika, filmový jazyk, Van Gogh, Beksiński, Strzemiński Keywords fine art, biography, picture, poetics, film language, Van Gogh, Beksiński, Strzemiński Prohlášení Prohlańuji, ņe jsem předkládanou práci zpracovala samostatně a pouņila jen uvedené prameny a literaturu. V Brně, dne 20. května 2019 Kateřina Hejnarová Poděkování Na tomto místě bych chtěla velmi poděkovat vedoucí mé práce Haně Slavíkové za cenné připomínky, za důvěru i psychickou podporu. -

Im Pressio Nist M O Dern & Co Ntem Po Rary Art 27 January

IMPRESSIONIST MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART CONTEMPORARY & MODERN IMPRESSIONIST 27 JANUARY 2015 8 PM 8 2015 JANUARY 27 27 JANUARY 2015 PM 8 2015 JANUARY 27 134 IMPRESSIONIST MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART CONTEMPORARY & MODERN IMPRESSIONIST VIEWINGS: Thu 15 Jan 5 pm - 10 pm Fri 16 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sat 17 Jan 10 pm - 12 am IMPRESSIONISSun - Thu /T 18-22, MO JanDERN 11 am - 10 pm Fri 23 Jan 11 am - 3 pm & CONSat T24EMPORAR Jan Y 10 pm - 12 am Sun - Mon / 25 - 26 Jan 11 am - 10 pm FINE TueAR 27T JanAUCTION 11 am - 8 pm JERUSALEM, JANUARY 27, 2015, 8 PM SALE 134 PREVIEW IN JERUSALEM: Thu 15 Jan 5 pm - 10 pm Fri 16 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sat 17 Jan 10 pm - 12 am Sun - Thu / 18-22 Jan 11 am - 10 pm Fri 23 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sat 24 Jan 10 pm - 12 am Sun - Mon / 25 - 26 Jan 11 am - 10 pm Tue 27 Jan 11 am - 8 pm PREVIEW IN NEW YORK: Thu 15 Jan 12 pm - 5 pm Fri 16 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sun - Thu / 18-22 Jan 12 pm - 5 pm Fri 23 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sun - Mon / 25 - 26 Jan 12 pm - 5 pm Tue 27 Jan 11 am - 1 pm PREVIEW & AUCTION MATSART GALLERY 21 King David St., Jerusalem tel +972-2-6251049 www.matsart.net בס"ד MATSART AUCTIONEERS & APPRAISERS 21 King David St., Jerusalem 9410145 +972-2-6251049 5 Frishman St., Tel Aviv 6357815 +972-3-6810001 415 East 72 st., New York, NY 10021 +1-718-289-0889 LUCIEN KRIEF OREN MIgdAL Owner, Director Head of Department Expert Israeli Art [email protected] [email protected] StELLA COSTA ALICE MARTINOV-LEVIN Senior Director Head of Department [email protected] Modern & Contemporary Art [email protected] EVGENY KOLOSOV YEHUDIT RATZABI AuctionAdministrator AuctionAdministrator Modern & Contemporary Art [email protected] [email protected] REIZY GOODWIN MIRIAM PERKAL Logistics & Shipping Client Accounts Manager [email protected] [email protected] All lots are sold “as is” and subject to a reserve. -

CHARLES HENRI MARIE VAN WIJK (The Hague 1875 – the Hague 1917)

CHARLES HENRI MARIE VAN WIJK (The Hague 1875 – The Hague 1917) Oude Vrouw haar Linnen Verstellende (Old Woman Mending her Linen) signed, inscribed, and dated CH.V. Wyk SCULPT 9 (?) on the base bronze, golden-brown patina 5 height: 15 ¼ inches (39.4 cm.), width: 8 /8 1 inches (22.5 cm.), depth: 12 /16 inches (31.4 cm.) PROVENANCE Private Collection, Illinois, until 2015 RELATED LITERATURE B.L. Voskuil, Jr., Tentoonstelling van bronzen door Charles van Wijk, Amsterdam, October 1901, no. 13, unpaginated Frank Buffa en Zonen, Tentoonstelling van beeldhouwwerken door Charles van Wijk, Amsterdam, 1910, no. 17 Maatschappij Arti et Amicitae, Amsterdam, 1911, no. 251 Veiling Nalatenschap Charles van Wijk, Kunstzaal Kleykamp, The Hague, November 27, 1917, lot 23 Helena Stork, “Oudje (of ‘Verstelwerk’)” in Charles van Wijk, exhibition catalog, Katwijks Museum, Katwijk, July 3 - September 25, 1999, p. 67 Charles van Wijk’s (or Wyk) practical training began in the foundry of his father Henry B. van Wijk in The Hague. Van Wijk’s skills in sculpting were obvious from a young age and encouraged by his father. Drawing lessons began with his uncle Arie Stortenbeker, an amateur painter, and at the age of twelve he was enrolled at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague. The chief instructor was the Belgian sculptor Antoine ‘Eugene’ Lacomblé who taught Van Wijk the art of modeling. The painter Fridolin Becker, another professor at the academy during this period, was also influential. Throughout his formal studies he continued to work in his father’s shop. After completing his schooling, Van Wijk was granted an internship at the famous Parisian foundry F. -

{FREE} Journal Oversized Almond Blossom

JOURNAL OVERSIZED ALMOND BLOSSOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Pauper Press,Vincent Van Gogh | 192 pages | 01 Jul 2010 | Peter Pauper Press Inc,US | 9781441303578 | English | White Plains, United States Almond Blossom Journal | Heart of the Home PA The works reflect the influence of Impressionism, Divisionism, and Japanese woodcuts. Almond Blossom was made to celebrate the birth of his nephew and namesake, son of his brother Theo and sister-in-law Jo. Now you can enjoy Almond Blossom on a daily basis. Well not all of it! To put this rectangular painting roughly 4x3 on products, we use as much of the painting as we can on each product. So for a square product like the shower curtain - we use a 3x3 rectangle - which cuts off a little of the sides - but is still very much Apple Blossoms For other products such as the wristlet a wide 4x1 rectangle - you get a small slice of the painting. Browse our system to see the full collection. If you are looking for something and do not find it, please contact us and we will do our best to meet your needs. As always with YouCustomizeIt, you can change anything about this design patterns, colors, graphics, etc. Our design library is loaded with options for you to choose from, or you can upload your own. Need Help? We could all benefit from a good, robust notebook at some point in our lives. These hardcover journals, are built to last and are the perfect means of storing your lists, thoughts, and notes. The hardcover of this personalized journal is covered with a smooth, matte, laminate coating. -

Mondrian and De Stijl

Exhibition November 11, 2020 – March 1, 2021 Sabatini Building, Floor 1 Mondrian and De Stijl Piet Mondrian, Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red (Picture no. III), 1938 Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection. © Mondrian/Holtzman, 2020 The work of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian within the context of the movement De Stijl [The Style] set the course of geometric abstract art from the Netherlands and contributed to the drastic change in visual culture after the First World War. His concept of beauty based on the surface, on the structure and composition of color and lines, shaped a novel and innovative style that aimed at breaking down the frontiers between disciplines and surpassing the traditional limits of pictorial space. De Stijl, the magazine of the same name founded in 1917 by the painter and critic Theo van Doesburg, was the platform for spreading the ideas of this new art and overcoming traditional Dutch provincialism. Contrary to what has often been said, the members of De Stijl did not pursue a utopia but a world where collaboration between all disciplines would make it possible to abolish hierarchies among the arts. These would thus be freed to merge together and give rise to something new, a reality better adapted to the world of modernity that was just starting to be glimpsed. Piet Mondrian (Amersfoort, Netherlands, 1872-New York, 1944) is considered one of the founders of this new art. His progressive ideas about the relationship between art and society grew from the deep- rooted Dutch realist tradition inherited from the seventeenth century. -

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair Professor John F. Connelly Professor Jeroen Dewulf Professor David W. Bates Spring 2012 Abstract The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and political reception of Critical Theory, as first developed in Germany by the “Frankfurt School” at the Institute of Social Research and subsequently reformulated by Jürgen Habermas, in the Netherlands from the mid to late twentieth century. Although some studies have acknowledged the role played by Critical Theory in reshaping particular academic disciplines in the Netherlands, while others have mentioned the popularity of figures such as Herbert Marcuse during the upheavals of the 1960s, this study shows how Critical Theory was appropriated more widely to challenge the technocratic directions taken by the project of vernieuwing (renewal or modernization) after World War II. During the sweeping transformations of Dutch society in the postwar period, the demands for greater democratization—of the universities, of the political parties under the system of “pillarization,” and of -

Vincent Van Gogh

Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) 19th century Netherlands and France Post-Impressionist Painter Vincent Van Gogh (Vin-CENT Van-GOKT??? [see page 2]) Post-Impressionist Painter Post-Impressionism Period/Style of Art B: 30 March 1853, Zundert, Netherlands D 29 July, 1890. Auvers-sur-Oise, France Van Gogh was the oldest surviving son born into a family of preacher and art dealers. When Vincent was young, he went to school, but, unhappy with the quality of education he received, his parents hired a governess for all six of their children. Scotswoman Anna Birnie was the daughter of an artist and was likely Van Gogh’s first formal art tutor. Some of our earliest sketches of Van Gogh’s come from this time. After school, Vincent wanted to be a preacher, like his father and grandfather. He studied for seminary with an uncle, Reverend Stricker, but failed the entrance exam. Later, he also proposed marriage to Uncle Stricker’s daughter…she refused (“No, nay, never!”) Next, as a missionary, Van Gogh was sent to a mining community, where he was appalled at the desperate condition these families lived in. He gave away most of the things he owned (including food and most of his clothes) to help them. His bosses said he was “over-zealous” for doing this, and ultimately fired him because he was not eloquent enough when he preached! Then, he tried being an art dealer under another uncle, Uncle Vincent (known as “Cent” in the family.) Vincent worked in Uncle Cent’s dealership for four years, until he seemed to lose interest, and left. -

Albert Lebourg 1849-1929

Albert Lebourg 1849-1929 Canal in Holland Oil on canvas / signed and dated 1896 lower left Dimensions : 39 x 55 cm Dimensions : 15.35 x 21.65 inch 32 avenue Marceau 75008 Paris | +33 (0)1 42 61 42 10 | +33 (0)6 07 88 75 84 | [email protected] | galeriearyjan.com Albert Lebourg 1849-1929 32 avenue Marceau 75008 Paris | +33 (0)1 42 61 42 10 | +33 (0)6 07 88 75 84 | [email protected] | galeriearyjan.com Albert Lebourg 1849-1929 Biography Born in the Eure department in Normandy, Albert Lebourg was only nineteen years old when he settled in Rouen to work with an architect. In the evening, he took painting and drawing lessons with Gustave Morin. Nevertheless, he quickly get bored of doing copies of antique plasters and prefered to paint outside, looking for inspiration in the surrounding countryside. In 1872, he was noticed by a collector who proposed him to become a drawing teacher at the Fine Arts school in Algiers, where he stayed for five years. During this time, Albert Lebourg devoted himself to painting, inspired by the light variations. He liked to paint l'Amirauté, its embankments and its green balconies, the mosque Jamaa al-Jdid, also named mosque of the Pêcherie, and the little streets of the white city. Lebourg often painted the same motifs at different moments of the day. His palette brightened and his style was completely impressionnist. However, the artist was still ignorant of this new artistic movement that he will discover when he got back in France in 1877.