A Book of Creatures a Book of Creatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

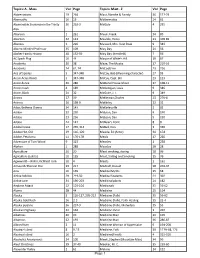

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

English As a Second Language Podcast ENGLISH CAFÉ – 546 TOPICS Paul Bunyan; American Songs – “You're the Top”; Big Ve

English as a Second Language Podcast www.eslpod.com ENGLISH CAFÉ – 546 TOPICS Paul Bunyan; American Songs – “You’re the Top”; big versus huge versus massive; at all and show off; to be beside (oneself) _____________ GLOSSARY legend – a story from the past that many people know and repeat but that may not be true, usually of an amazing person or event * There is a legend about a ship carrying millions of gold coins which sank in the Caribbean Ocean over two hundred years ago. axe – a tool with a wooden handle and a heavy metal blade that is used for chopping wood * The firefighter swung his axe to chop down the door of the burning building to save the trapped people inside. lumberjack – a person whose job is to cut down trees that are used in building * The lumberjacks worked in teams in the woods to fell trees. canyon – a deep valley (low area between mountains) with steep and rocky sides, often with a river at the bottom * It would take a hiker several days to hike to the bottom of this canyon. hero – a person who is admired for his or her bravery or important actions * In our community, we are surrounded by real-life heroes who risk their own lives for other people, but who are unrecognized. mainstream – ideas, views, and activities that are considered normal or shared by most people * Names like Ethel and Bertha used to be considered mainstream in the U.S. but are not popular today. chopping block – a hard, usually round, piece of wood on which things such as meat, vegetables, or wood are cut * The chef put the large piece of meat on the chopping block and carefully cut it into thin steaks. -

Doc Brewer, Brewer's Backwoods

BREWER’S BACKWOODS Fearsome critters, strange flora, and fabled treasures lie beyond Fort Brewer A one-page wilderness adventure created by Doc Brewer MAP KEY (1 HEX = 10 MILES) 0100: A baneful aura lingers in this comet blast zone 0913: Fort Brewer, plus respectable New Town, seedy Old Town 0112: Enclave of druids—will they help you, or sacrifice you? 1001: An ancient evil dwells in the bottomless pool 0204: Nesting grounds of the fearsome Hodag; eggs are priceless 1006: Nocturnal horned-folk stalk these dense, dark woods 0209: Island of cursed souls who rise after nightfall 1110: Sinkholes dot the landscape; some are inhabited 0210: Dryad grove; rare and precious wood is a lure to loggers 1209: Whispers echo up and down natural limestone caves 0307: A Lorelei sings from atop a rock to enchant passersby 1212: Wellman’s Wade: crossing, trading post and gathering place 0312: Standing stone circle acts as a gate, but the secret is lost 1306: Limestone cave system leads to inky river underground 0403: What lurks behind the mists of the weird waterfall? 1313: The moonshiners in these hollows value their privacy 0509: Silver mine abandoned after too many men went missing 1404: Standing stone circle; the other end of the gate in 0312 0511: Lumberton, last outpost of loggers and hunters 1411: Reward to be had for rooting out river reavers’s roost 0513: Two clans of witches have feuded here for generations 1508: When the Pineys come out of their hiding holes, it’s too late 0606: Hidebehind that hunts here is the last thing you’ll never see 1601: -

TRADEBOOK LIST(Alphabetical)

K-5 Approved Trade Book List 12.14.16 Grade Approved Lexile $$$ (DOLLARS) HEWETSON 1 x …AND NOW MIGUEL KRUMGOLD 5 780L 10 FOR DINNER BOGART 1 820 26 LETTERS AND 99 CENTS HOBAN. T. K x 2-B AND THE ROCK 'N ROLL BAND PAUL 1 x 2-B AND THE SPACE VISITOR PAUL 1 x 500 HATS OF BARTHOLOMEW CUBBINS, THE SEUSS 3 520L A BEAR CALLED PADDINGTON BOND 4 750L A IS FOR ALPHABET CATHY, MARLY A 2 x A MY NAME IS ALICE BAYER 1 370 A, B, SEE HOBAN, T. K x ABE LINCOLN, THE YOUNG YEARS BRANDT 3 0 ABOUT TIME: A FIRST LOOK AT TIME AND CLOCKS KOSCIELNIAK 4 1200L ABUELA DORROS 2 510 ABUELO'S QUIET DAYS THOMAS 1 x ACROSS FIVE APRILS HUNT 5 1100L ADDIE ACROSS THE PRAIRIE LAWLOR 4 820L ADDIE MEETS MAX ROBINS 1 310 ADVENTURE AT THE WAX MUSEUM SUNSHINE 4 0 ADVENTURES OF ALI BABA BERNSTEIN, THE HURWITZ 2 650 ADVENTURES OF SPIDER, THE ARKHURST 3 710L ADVENTURES WITH CROM GRANOWSKY 1 x ADVICE NELSON 1 x AGE OF INVENTIONS, THE ROSSI 5 650L AH, MUSIC ALIKI 3 910L AIR IS ALL AROUND YOU BRANLEY 3 330L AIRPLANES ROCKWELL 1 x AIRPORT BARTON 1 400 AL MAKAR 1 x ALBERT THE ALBATROSS HOFF 1 x ALDO ICE CREAM HURWITZ 3 770L ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD VIORST 2 970 ALEXANDER AND THE WIND-UP MOUSE LIONNI 2 490 ALEXANDER, WHO USED TO BE RICH LAST SUNDAY VIORST 3 570L ALL ABOARD THE TRAIN KESSLER 2 x ALL ABOUT SAM LOWRY 4 670L ALL ABOUT SEEDS KUCHALLA 2 x ALL ABOUT YOU ANHOLT 1 60 ALL BY MYSELF MAYER 1 370 ALL MINE HARTLEY 1 x ALL PIGS ARE BEAUTIFUL KING-SMITH 2 890 ALLIGATOR GRANOWSKY 1 x ALLIGATOR ARRIVED WITH APPLES DRAGONWAGON K 340 ALMOND BLOSSOM SOUTHGATE-EDI 2 x -

Table of Contents

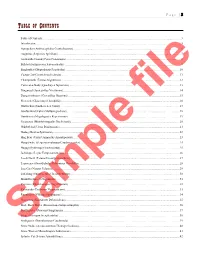

P a g e | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Agropelter (Anthrocephalus Craniofractens) ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Augerino (Serpentes Spirillum) ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Axehandle Hound (Canis Consumens).......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Billdad (Saltipiscator Falcorostratus) ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 Bingbuffer (Glyptodontis Petrobolus) ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Cactus Cat (Cactifelinus Inebrius).............................................................................................................................................................. -

1. American Folklore Creatures

1. American Folklore Creatures 1 1. Abbagoochie >The abbagoochie (pronounced abba-GOO-cheez) is a fierce little creature resembling a cross between an owl, a fox, and a deer. It is indigenous to Costa Rica, where people refer to it as a "dryland piranha" because it will eat anything, including creatures far larger than itself such as horses and cows. If cornered, an abbagoochie will consume itself "in a devilish whirlwind" rather than allow itself to be captured. They mate only once every 6 ½ years. 2. The Alkali Monster >This gargantuan, mono-horned, foul smelling, reptilian beast is reputed to lurk in the depths of Nebraska’s famed Alkali Lake, devouring all who come near it. Located in central Nebraska, Walgren Lake (formerly known as Alkali Lake) is an eroded volcanic outcropping that is reputed to be the nesting place of one of the most unusual lake monsters ever recorded and, if the legends are true, the habitat of the only aquatic monster ever reported in the state of Nebraska. Originally chronicled in Native American folklore, this creature has been described as a gargantuan alligator-like beast with some unique attributes. Eyewitnesses claim that the beast is approximately 40-feet long, with rough, grayish-brown skin and a horny outgrowth located between its eyes and nostrils. 3. The Altamaha-ha >Local legend reports a 20-foot-long water serpent that dwarfs the size of alligators in the region. It lives where the Altahama River dumps into the Atlantic Ocean, and thus a host of very real sea creatures have been suggested as explanations for the beast. -

America's Fearsome Creatures

America’s Fearsome Creatures By Aoty 1 43. A Composite Monster 1. The Abbagoochie 44. Commodore Preble’s Monster 2. The Alkali Monster 45. The Cougar Fish 3. The Altamaha-ha 46. The Cuba 4. Amhuluk 47. The Devil-Jack Diamond Fish 5. Angont 48. The Dewayo 6. Apotamkin 49. The Dew Mink 7. The Argopelter 50. The Ding-ball 8. The Arkansas Snipe 51. The Dingbat 9. The Augerino 52. The Double Rat 10. The Axehandle Hound 53. The Dubuque Monster Reptile 11. The Backus Monster 54. The Duck-Footed Dum DUm 12. The Balloon Fish 55. The Dungavenhooter 13. The Bassigator 56. The Fire-Starter Beast 14. The Bear Lake Monster 57. The Fish-Fox 15. The Beazel 58. The Fish-Hound 16. The Bildad 59. The Flittericks 17. The Biloxi Bay Devil Fish 60. The Flying Serpents 18. The Bird of Winnemucca 61. The Funeral Mountain Terrashot 19. The Black Dog 62. The Gaasyendietha 20. The Black Newfoundland DOg 63. The Galliwampus 21. The Black Hodag 64. The Gallywampus 22. The Black Fox of Salmon River 65. The Gazerium and Snydae 23. The Boat Hound 66. The Gazunk, or The Flute Bill 24. The Bone-Headed Penguin 67. The Godaphro 25. The Booger Dog 68. The Golden Bears 26. The Boont 69. The Gollywog 27. The Brazilian Trench Digger 70. The Goofang 28. The Bright Old Inhabitants 71. The Goofus Bird 29. The Bull of Durham 72. The Giant Lobster 30. The Cactus Cat 73. The Giddy Fish 31. Caldera Dick 74. The Gigantic Feathered Creature 32. -

Post/Teca 03.2012

Post/teca materiali digitali a cura di sergio failla 03.2012 ZeroBook 2012 Post/teca materiali digitali Di post in post, tutta la vita è un post? Tra il dire e il fare c'è di mezzo un post? Meglio un post oggi che niente domani? E un post è davvero un apostrofo rosa tra le parole “hai rotto er cazzo”? Questi e altri quesiti potrebbero sorgere leggendo questa antologia di brani tratti dal web, a esclusivo uso e consumo personale e dunque senza nessunissima finalità se non quella di perder tempo nel web. (Perché il web, Internet e il computer è solo questo: un ennesimo modo per tutti noi di impiegare/ perdere/ investire/ godere/ sperperare tempo della nostra vita). In massima parte sono brevi post, ogni tanto qualche articolo. Nel complesso dovrebbero servire da documentazione, zibaldone, archivio digitale. Per cosa? Beh, questo proprio non sta a me dirlo. Buona parte del materiale qui raccolto è stato ribloggato anche su girodivite.tumblr.com grazie al sistema di re-blog che è possibile con il sistema di Tumblr. Altro materiale qui presente è invece preso da altri siti web e pubblicazioni online e riflette gli interessi e le curiosità (anche solo passeggeri e superficiali) del curatore. Questo archivio esce diviso in mensilità. Per ogni “numero” si conta di far uscire la versione solo di testi e quella fatta di testi e di immagini. Quanto ai copyright, beh questa antologia non persegue finalità commerciali, si è sempre cercato di preservare la “fonte” o quantomeno la mediazione (“via”) di ogni singolo brano. Qualcuno da qualche parte ha detto: importa certo da dove proviene una cosa, ma più importante è fino a dove tu porti quella cosa. -

STORY GUIDE (Digest Size)

A M A K E Y O U R O W N A D V E N T U R E G A M E Cover Art: Jacob Philipp Hackert, Fischerfamilie am nächtlichen Lagerfeuer mit aufgewühltem Meer (1778) Art: Joseph Wright of Derby, Cottage on Fire at Night (1785 between 1793) Allsopp, Fred W. Twenty Years in a Newspaper Office. Little Rock: Central Printing Company, 1907. Botkin, Benjamin A. A Treasury of American Folklore. New York: Crown Publishers, 1955. Boyton, Patrick. Snallygaster: The Lost Legend of Frederick County. Maryland: Self-Published, 2008. Brown, Charles E. Paul Bunyan Tales. Madison: self-published, 1922. Brown, Charles E. The Wild Animals of Paul Bunyan's Northwoods. Madison: self-published, 1935. Cohen, Daniel. Monsters, Giants, and Little Men from Mars: An Unnatural History of the Americas. New York: Doubleday, 1975 Childs, Art. Yarns of the Big Woods (circa 1925). Charlotte, NC: Thrill Land, 2015. 12 “A Corner in Paradise as Part Payment from France.” The New York Tribune, January 26, 1919. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1919-01-26/ed-1/seq-25/. Cox, William T. Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods. Washington: Judd & Detweiler, 1910. Dahlgren, Madeleine V. South Mountain Magic. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1882. Dolezal, Robert et al. American Folklore and Legend. New York: Reader's Digest, 1981. Dorson, Richard M. Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers: Folk Tales of Canadians, Lumberjacks and Indians. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008. Dorson, Richard M. "The Lumberjack Code." Western Folklore 8, no. 4 (1949): 358-65. doi:10.2307/1496154. -

Unusual Animals Compiled by Daniel R

Unusual Animals Compiled by Daniel R. Mott: Roundtable Staff District 23, West Jordan, Utah Here is a collection of animals that can be found in American myth and lore. If you really look for them you may even be able to find them. Snawfus Just after the sun goes down look in the treetops . If you are luck you will see a Snawfus. A is a white deer with giant antlers from which flowers grow. As it leaps from tree to tree it sings, Halley-loo! Halley-loo! One variety exhales a blue smoke which produces an autumn haze in the Ozark Mountains. Squonk A Squonk never sings. It is so upset by the way it looks, it cries all the time. A famous hunter named Mule McSneed once caught a by following its teardrops. Then he stuck it into a sack and took it home. But the cried so hard that when he opened the sack that all there was left was a puddle of water. Similar to a whangdoodle. Milamo Bird A Milamo bird eats giant worms that live in giant wormholes. When it gets hungry, it dives into one of these holes and finds itself a worm. The bird pulls in one direction and the worm in the other. But each time the bird pulls, the worm stretches a little and when the worm pulls back the worm stretches a little more, like a rubber band. When finally the worm is stretched too thin, it gives up and lets go. Then the worm shoots out of the hole like a shot and smacks the bird between the eyes, jumping back into its hole. -

K-5 Approved Trade Book List

K-5 Approved Trade Book List 12.14.16 Grade Approved Lexile $$$ (DOLLARS) HEWETSON 1 x 10 FOR DINNER BOGART 1 820 2-B AND THE ROCK 'N ROLL BAND PAUL 1 x 2-B AND THE SPACE VISITOR PAUL 1 x A MY NAME IS ALICE BAYER 1 370 ABUELO'S QUIET DAYS THOMAS 1 x ADDIE MEETS MAX ROBINS 1 310 ADVENTURES WITH CROM GRANOWSKY 1 x ADVICE NELSON 1 x AIRPLANES ROCKWELL 1 x AIRPORT BARTON 1 400 AL MAKAR 1 x ALBERT THE ALBATROSS HOFF 1 x ALL ABOUT YOU ANHOLT 1 60 ALL BY MYSELF MAYER 1 370 ALL MINE HARTLEY 1 x ALLIGATOR GRANOWSKY 1 x AM I ? HEWETSON 1 x AMELIA BEDELIA AND THE SURPRISE SHOWER PARISH 1 270 AMELIA BEDELIA GOES CAMPING PARISH 1 110 AMELIA BEDELIA HELPS OUT PARISH 1 210 AMERICAN BALD EAGLE GRANOWSKY 1 x AMERICAN BISON GRANOWSKY 1 x ANANSI AND THE MOSS-COVERED ROCK KIMMEL 1 380 AND TO THINK I SAW IT ON MULBERRY STREET SEUSS 1 x ANIMALS AT THE ZOO GREYDANUS 1 x ANIMALS OF THE WORLD GRANOWSKY 1 x ANIMALS TRACKS DORROS 1 540 ANNA BANANA AND ME BELGVAD 1 290 ANNA'S GARDEN SONG STEELE 1 x ANNIE AND THE WILD ANIMALS BRETT 1 490 APPLE, AN NELSON 1 x ARA'S AMAZING SPINNING WHEEL COLLINS 1 x ARTHUR'S BABY BROWN 1 310 AS LIGHT AS A FEATHER NELSON 1 x AT THE BEACH RAABE 1 x AT THE POND RAABE 1 x AT THE SHORE EBERTS 1 x AT THE TOWER CROCKETT 1 x AT THE ZOO VAN ALLEN 1 x AT TOM'S HOUSE MODARESSI 1 x AUNT JOAN'S JOKE HARTLEY 1 x AWAY GO THE BOATS HILLERT 1 x AWAY THEY RAN MODARESSI 1 x BABE, THE BIG HIT MAKAR 1 x BABY BUNNY, THE HILLERT 1 BR BABY PANDA AT THE FAIR ALLEN 1 x BACK PACKS, THE HEWETSON 1 x BACKYARD INSECTS SELSAM 1 660 BAD CAT - PSST! MCDONALD 1 x BAD DAN HEWETSON 1 x BALL AND THE MITT, THE NELSON 1 x BALL BOOK, THE HILLERT 1 BR BALLOON MAGIC ADAMS 1 x BATH TIME RAABE 1 x BE CAREFUL, SLOPPY TIGER! COWLEY 1 x BEAR HODKINSON 1 x BEAR SHADOW ASCH 1 580 BEAR UNDER THE STAIRS, THE COOPER 1 x BEARS KRAUSS 1 BR BEAUTIFUL BREEZY BLUE AND WHITE DAY ALLEN 1 x BECKY, THE RABBIT DARBY 1 x BEDTIME FOR FRANCES HOBAN, R.