Folklore Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

*Certain Exceptions Apply ® MARCH 2016 Muse Volume 20, Issue 03 VP of EDITORIAL & CONTENT Catherine “Lark” Connors DIRECTOR of EDITORIAL James M

® muMARCH 2016 se NO FOOLING* *certain exceptions apply ® MARCH 2016 muse Volume 20, Issue 03 VP OF EDITORIAL & CONTENT Catherine “Lark” Connors DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL James M. “Scheme” O’Connor FEATURES EDITOR Johanna “Tomfoolery” Arnone CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Meg “Mischief” Moss CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Kathryn “High Jinks” Hulick ASSISTANT EDITOR Jestine “Jest” Ware ART DIRECTOR Nicole “Prank” Welch DESIGNER Jacqui “Joke” Ronan Whitehouse DIGITAL DESIGNER Kevin “Trick” Cuasay RIGHTS & PERMISSIONS David “Spoof” Stockdale BOARD OF ADVISORS ONTARIO INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES IN EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Carl Bereiter ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO John A. Brinkman NATIONAL CREATIVITY NETWORK Dennis W. Cheek COOPERATIVE CHILDREN’S BOOK CENTER, A LIBRARY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON K. T. Horning FREUDENTHAL INSTITUTE Jan de Lange FERMILAB Leon Lederman UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Sheilagh C. Ogilvie WILLIAMS COLLEGE Jay M. Pasachoff UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Paul Sereno 10 (Don’t) Fly Me to the Moon Calling all conspiracy theorists by Lela Nargi 16 20 26 40 Not ActuAl Size Rooked! WhAt Killed the WhAt’S So FuNNy? The many faces of caricature The true story diNoSAurS? How we learn to laugh by Kristina Lyn Heitkamp behind a fake robot A theory on trial by Kathiann M. Kowalski by Nick D’Alto by Jeanne Miller CONTENTS VP OF EDITORIAL & CONTENT Catherine “Lark” Connors DIRECTOR OF EDITORIAL James M. “Scheme” O’Connor EDITOR Johanna “Tomfoolery” Arnone DEPARTMENTSDEPARTMENTS CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Meg “Mischief” Moss CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Kathryn “High Jinks” Hulick ASSISTANT EDITOR Jestine “Jest” Ware 2 Parallel U ART DIRECTOR Nicole “Prank” Welch by Caanan Grall DESIGNER Jacqui “Joke” Ronan Whitehouse DIGITAL DESIGNER Kevin “Trick” Cuasay 6 Muse News RIGHTS & PERMISSIONS David “Spoof” Stockdale by Elizabeth Preston 47 Your Tech BOARD OF ADVISORS by Kathryn Hulick ONTARIO INSTITUTE FOR STUDIES IN EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Carl Bereiter 48 Last Slice ORIENTAL INSTITUTE, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO by Nancy Kangas John A. -

Preserving Florida's Heritage

Preserving Florida’s Heritage MMoorree TThhaann OOrraannggee MMaarrmmaallaaddee Florida’s Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan 2012 - 2016 Florida Department of State Division of Historical Resources TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION Page 1 Viva Florida Why Have a Statewide Historic Preservation Plan? CHAPTER 1 OVERVIEW OF FLORIDA’S PRE-HISTORY & HISTORY Page 4 CHAPTER 2 PLANNING IN FLORIDA, A PUBLIC POLICY Page 8 CHAPTER 3 PRESERVATION PARTNERS Page 12 Federal Government Seminole Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) State Government Other Florida Department of State Programs Advisory Boards and Support Organizations Other State Agencies Formal Historic Preservation Academic Programs Local Governments Non-Profit Organizations CHAPTER 4 FLORIDA’S RESOURCES, AN ASSESSMENT Page 36 Recent Past Historic Landscapes Urbanization and Suburbanization Results from Statewide Survey of Local Historic Preservation Programs African-American Resources Hispanic Resources Transportation Religion Maritime Resources Military Recreation and Tourism Industrialization Folklife Resources CHAPTER 5 HOW THIS PLAN WAS DEVELOPED Page 47 Public Survey Survey Results Meetings Findings Timeframe of the Plan and Revisions CHAPTER 6 GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND SUGGESTED STRATEGIES Page 53 Vision Statement for Historic Preservation in Florida CHAPTER 7 A BRIEF TIMELINE OF FLORIDA HISTORY Page 63 CHAPTER 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND OTHER RESOURCES Page 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY USEFUL LINKS FLORIDA’S HISTORICAL CONTEXTS MULTIPLE PROPERTY SUBMISSION COVERS Archaeological Thematic or Property Types Local Areas HERITAGE TRAILS SOCIAL MEDIA ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The preparation of a statewide comprehensive historic preservation plan intended for everyone across the state involved many people. We are greatly appreciative of the regional staff from the Florida Public Archaeology Network (FPAN) who hosted public meetings in five communities across the state, and to Jeannette Peters, the consultant who so ably led those meetings. -

Teaching the First American Civilization Recognizing the Moundbui

The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies Volume 77 Article 2 Number 2 Volume 77 No. 2 (2016) June 2016 Teaching The irsF t American Civilization Recognizing The oundM builders as a Great Native-American Civilization Jack Zevin Queens College/CUNY Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Elementary Education Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, Geography Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Pre- Elementary, Early Childhood, Kindergarten Teacher Education Commons Recommended Citation Zevin, Jack (2016) "Teaching The irF st American Civilization Recognizing The oundM builders as a Great Native-American Civilization," The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies: Vol. 77 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/the_councilor/vol77/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ouncC ilor: A Journal of the Social Studies by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zevin: Teaching The First American Civilization Recognizing The Moundbui Teaching The First American Civilization Recognizing The Moundbuilders as a Great Native-American Civilization Jack Zevin Queens College/CUNY The Moundbuilders are a culture of mystery, little recognized by most Americans, yet they created farms, villages, towns, and cities covering as much as a third of the United States. Social studies teachers have yet to mine the resources left us over thousands of years by the native artisans and builders who preceded the nations European explorers came into contact with after 1492. -

The Edward Houstoun Plantation Tallahassee,Florida

THE EDWARD HOUSTOUN PLANTATION TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA INCLUDING A DISCUSSION OF AN UNMARKED CEMETERY ON FORMER PLANTATION LANDS AT THE CAPITAL CITY COUNTRY CLUB Detail from Le Roy D. Ball’s 1883 map of Leon County showing land owned by the Houstoun family.1 JONATHAN G. LAMMERS APRIL, 2019 adlk jfal sk dj fsldkfj Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 The Houstoun Plantation ................................................................................................................................. 2 Edward Houstoun ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Patrick Houstoun ........................................................................................................................................... 6 George B. Perkins and the Golf Course .................................................................................................. 10 Golf Course Expansion Incorporates the Cemetery .......................................................................... 12 The Houstoun Plantation Cemetery ............................................................................................................. 15 Folk Burial Traditions ................................................................................................................................. 17 Understanding Slave Mortality .................................................................................................................. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM Holden Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.1 3.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.6 0.5 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 4.8 2.0 English Fiction 6201 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen LG 3.1 2.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 5.2 5.0 English Fiction 9001 The 500 Hats of Bartholomew CubbinsDr. Seuss LG 3.9 1.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 11151 Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner LG 2.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 61248 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved BooksKay Winters LG 3.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 101 Abel's Island William Steig MG 6.2 3.0 English Fiction 13701 Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Jean Brown Wagoner MG 4.2 3.0 English Nonfiction 9751 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger LG 2.8 0.5 English Fiction 907 Abraham Lincoln Ingri & Edgar d'Aulaire 4.0 1.0 English 31812 Abraham Lincoln (Pebble Books) Lola M. Schaefer LG 1.5 0.5 English Nonfiction 102785 Abraham Lincoln: Sixteenth President Mike Venezia LG 5.9 0.5 English Nonfiction 6001 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith LG 5.0 3.0 English Fiction 102 Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt MG 8.9 11.0 English Fiction 7201 Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg LG 1.2 0.5 English Fiction 17602 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie:Kristiana The Oregon Gregory Trail Diary.. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

The Mediaeval Bestiary and Its Textual Tradition

THE MEDIAEVAL BESTIARY AND ITS TEXTUAL TRADITION Volume 1: Text Patricia Stewart A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3628 This item is protected by original copyright The Mediaeval Bestiary and its Textual Tradition Patricia Stewart This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 17th August, 2012 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Patricia Stewart, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in May, 2008; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2007 and 2012. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

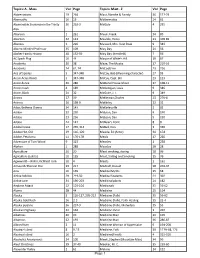

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Dragon Magazine #248

DRAGONS Features The Missing Dragons Richard Lloyd A classic article returns with three new dragons for the AD&D® game. Departments 26 56 Wyrms of the North Ed Greenwood The evil woman Morna Auguth is now The Moor Building a Better Dragon Dragon. Paul Fraser Teaching an old dragon new tricks 74Arcane Lore is as easy as perusing this menu. Robert S. Mullin For priestly 34 dragons ... Dragon Dweomers III. Dragon’s Bestiary 80 Gregory W. Detwiler These Crystal Confusion creatures are the distant Dragon-Kin. Holly Ingraham Everythingand we mean everything 88 Dungeon Mastery youll ever need to know about gems. Rob Daviau If youre stumped for an adventure idea, find one In the News. 40 92Contest Winners Thomas S. Roberts The winners are revealed in Ecology of a Spell The Dragon of Vstaive Peak Design Contest. Ed Stark Columns Theres no exagerration when Vore Lekiniskiy THE WYRMS TURN .............. 4 is called a mountain of a dragon. D-MAIL ....................... 6 50 FORUM ........................ 10 SAGE ADVICE ................... 18 OUT OF CHARACTER ............. 24 Fiction BOOKWYRMs ................... 70 The Quest for Steel CONVENTION CALENDAR .......... 98 Ben Bova DRAGONMIRTH ............... 100 Orion must help a young king find both ROLEPLAYING REVIEWS .......... 104 a weapon and his own courage. KNIGHTS OF THE DINNER TABLE ... 114 TSR PREVIEWS ................. 116 62 PROFILES ..................... 120 Staff Publisher Wendy Noritake Executive Editor Pierce Watters Production Manager John Dunn Editor Dave Gross Art Director Larry Smith Associate Editor Chris Perkins Editorial Assistant Jesse Decker Advertising Sales Manager Bob Henning Advertising Traffic Manager Judy Smitha On the Cover Fred Fields blends fantasy with science fiction in this month's anniversary cover. -

West Virginia Folklife Program Presents Concert with Ballad Singer Phyllis Marks, September 8 for Immediate Release Contact: Em

West Virginia Folklife Program Presents Concert with Ballad Singer Phyllis Marks, September 8 For Immediate Release Contact: Emily Hilliard 304.346.8500 August 30, 2016 [email protected] Charleston— On the evening of Thursday, September 8, The West Virginia Folklife Program, a project of the West Virginia Humanities Council, will present a concert by West Virginia ballad singer Phyllis Marks. The concert will be held from 5:30-7:30pm at the historic MacFarland-Hubbard House, headquarters of the West Virginia Humanities Council (1310 Kanawha Blvd. E) in Charleston. The free event will include a performance, question-answer session, and reception, and will be recorded and archived at the Library of Congress. Phyllis Marks, age 89, is according to folklorist Gerry Milnes the last active ballad singer in the state who “learned by heart” via oral transmission. Marks was recorded for the Library of Congress in 1978 and has performed for 62 years at the West Virginia State Folk Festival in her hometown of Glenville. Phyllis Marks is among West Virginia’s finest traditional musicians and a master of unaccompanied Appalachian ballad singing. Following her performance, Marks will give a brief interview with West Virginia University musicology professor and West Virginia native Travis Stimeling. “West Virginia Folklife Presents Ballad Singer Phyllis Marks” is supported by ZMM Architects & Engineers in Charleston and The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress’ 2016 Henry Reed Fund Award. Established in 2004 with an initial gift from founding AFC director Alan Jabbour, the fund provides small awards to support activities directly involving folk artists, especially when the activities reflect, draw upon, or strengthen the archival collections of the AFC.