The Bestiary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mediaeval Bestiary and Its Textual Tradition

THE MEDIAEVAL BESTIARY AND ITS TEXTUAL TRADITION Volume 1: Text Patricia Stewart A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3628 This item is protected by original copyright The Mediaeval Bestiary and its Textual Tradition Patricia Stewart This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 17th August, 2012 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Patricia Stewart, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in May, 2008; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2007 and 2012. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

Dragon Magazine #248

DRAGONS Features The Missing Dragons Richard Lloyd A classic article returns with three new dragons for the AD&D® game. Departments 26 56 Wyrms of the North Ed Greenwood The evil woman Morna Auguth is now The Moor Building a Better Dragon Dragon. Paul Fraser Teaching an old dragon new tricks 74Arcane Lore is as easy as perusing this menu. Robert S. Mullin For priestly 34 dragons ... Dragon Dweomers III. Dragon’s Bestiary 80 Gregory W. Detwiler These Crystal Confusion creatures are the distant Dragon-Kin. Holly Ingraham Everythingand we mean everything 88 Dungeon Mastery youll ever need to know about gems. Rob Daviau If youre stumped for an adventure idea, find one In the News. 40 92Contest Winners Thomas S. Roberts The winners are revealed in Ecology of a Spell The Dragon of Vstaive Peak Design Contest. Ed Stark Columns Theres no exagerration when Vore Lekiniskiy THE WYRMS TURN .............. 4 is called a mountain of a dragon. D-MAIL ....................... 6 50 FORUM ........................ 10 SAGE ADVICE ................... 18 OUT OF CHARACTER ............. 24 Fiction BOOKWYRMs ................... 70 The Quest for Steel CONVENTION CALENDAR .......... 98 Ben Bova DRAGONMIRTH ............... 100 Orion must help a young king find both ROLEPLAYING REVIEWS .......... 104 a weapon and his own courage. KNIGHTS OF THE DINNER TABLE ... 114 TSR PREVIEWS ................. 116 62 PROFILES ..................... 120 Staff Publisher Wendy Noritake Executive Editor Pierce Watters Production Manager John Dunn Editor Dave Gross Art Director Larry Smith Associate Editor Chris Perkins Editorial Assistant Jesse Decker Advertising Sales Manager Bob Henning Advertising Traffic Manager Judy Smitha On the Cover Fred Fields blends fantasy with science fiction in this month's anniversary cover. -

The Unicorn Tapestries: Religion, Mythology, and Sexuality in Late Medieval Europe

The Unicorn Tapestries: Religion, Mythology, and Sexuality in Late Medieval Europe The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Pansini, Stephanie Rianne. 2020. The Unicorn Tapestries: Religion, Mythology, and Sexuality in Late Medieval Europe. Master's thesis, Harvard University Division of Continuing Education. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367690 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Unicorn Tapestries: Religion, Mythology, and Sexuality in Late Medieval Europe Stephanie Rianne Pansini A Thesis in the Field of Anthropology & Archaeology for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2021 Copyright 2021 Stephanie Rianne Pansini Abstract The Unicorn Tapestries are a set of seven tapestries, located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters in New York, of Parisian design and woven in the Southern Netherlands in the late Middle Ages. It has baffled scholars for decades. These tapestries are shrouded in mystery, especially considering their commissioner, narratives, and sequence of hanging. However, for whom and how they were made is of little importance for this study. The most crucial question to be asked is: why the unicorn? What was the significance of the unicorn during the late Middle Ages? The goal of this thesis is to explore the evolution of the unicorn throughout the Middle Ages as well as important monarchal figures and central themes of aristocratic society during the period in which the tapestries were woven. -

Animal Creatures and Creation

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1998 Volume II: Cultures and Their Myths Universal Myths and Symbols: Animal Creatures and Creation Curriculum Unit 98.02.05 by Pedro Mendia-Landa Mythology and mythological ideas permeate all languages, cultures and lives. Myths affect us in many ways, from the language we use to how we tell time; mythology is an integral presence. The influence mythology has in our most basic traditions can be observed in the language, customs, rituals, values and morals of every culture, yet the limited extent of our knowledge of mythology is apparent. In general we have today a poor understanding of the significance of myths in our lives. One way of studying a culture is to study the underlying mythological beliefs of that culture, the time period of the origins of the culture’s myths, the role of myth in society, the symbols used to represent myths, the commonalties and differences regarding mythology, and the understanding a culture has of its myths. Such an exploration leads to a greater understanding of the essence of a culture. As an elementary school teacher I explore the role that mythology plays in our lives and the role that human beings play in the world of mythology. My objective is to bring to my students’ attention stories that explore the origins of the universe and the origins of human kind, and to encourage them to consider the commonalties and differences in the symbols represented in cross-cultural universal images of the creation of the world. I begin this account of my unit by clarifying the differences between myth, folklore, and legend, since they have been at times interchangeably and wrongly used. -

HERO Bestiary 1 HERO Bestiaryª

HERO Bestiary 1 HERO Bestiary™ CREDITS Author: Doug Tabb Contributing Authors: Darrin C. Zielinski, Brian Nystul, Mark Bennett Editors: George MacDonald, Steve Peterson, and Coleman Charlton Cover Illustration: Storn Cook Colorist: Frank Cirocco Interior Illustration: Storn Cook, Stephan Peregrine, Mitch Byrd, Paul Jaquays, Liz Danforth, Albert Deschesne, Dennis Loubet, Luther, Elissa Martin, Darrell Midgette, Giorgia Ponticelli, Roger Raupp, Paulo Romano, Shawn Sharp, Jason Waltrip. A bibliography for the Dover Publication art and copyright free art used in this product can be found on the last page. Project Specific Contributions: Pagemaking & Layout: Coleman Charlton; Cover Graphics: Terry K. Amthor; Art Direction: Jessica Ney; Editorial Contributions: Ray Greer, Monte Cook Proofreading: Lori Ralston Dedication: To Gary Gygax who gave me role-playing games; to George MacDonald and Steve Peterson who gave me the rules; to Rob Bell who gave me a chance; to Ray Greer who treated me like a real human being; and to Jim, my long time collaborator. ICE Staff — Sales Manager: Deane Begiebing; Editing & Development Manager: Coleman Charlton; President: Peter Fenlon; CEO: Bruce Neidlinger; Editing, Development, & Production Staff: Kevin Barrett, Monte Cook, Jessica Ney, Pete Fenlon, Terry Amthor; Sales, Customer Service & Operations Staff: Heike Kubasch, Chad McCully; Shipping Staff: John Breckenridge, Jasper Merendino, Sterling Williams. HERO Bestiary™ is Hero Games’ trademark for its superhero roleplaying game using the Hero system. Champions® and Champions, The Super Roleplaying Game™ are Hero Games trademarks for its superhero roleplaying game using the Hero System. Hero System™ is Hero Games’ trademark for its roleplaying system. HERO Bestiary Copyright © 1992 Hero Games. All rights reserved. -

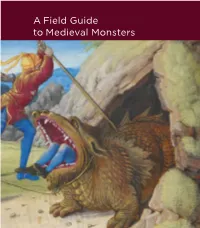

A Field Guide to Medieval Monsters Unicorns

A Field Guide to Medieval Monsters Unicorns. Griffins. Dragons. Sirens. Some of these monsters you may recognize from fairy July 7–October 6 tales, Greek and Roman mythology, or books about your favorite boy wizard. In the Middle Ages, these monsters and many more made their way onto the pages of illuminated manu- scripts. These handwritten texts, which include bibles, books of hours, and books of psalms, were often decorated with elaborate designs and images. This exhibition, Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders, explores how images of monsters played a complex role in medi- eval society and operated in a variety of ways, often instilling fear, revulsion, devotion, or wonderment. Medieval Monsters is organized by the Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Supporting Sponsor: The Womens Council of the Cleveland Museum of Art Media Sponsor: Before you start You are ready to go! Use exploring, there is some this field guide to identify monster terminology monsters you encounter you may need to know. throughout the exhibition. Anthropomorphic a creature or object having humanlike Basilisk a reptile or serpent who can Livre des merveilles du monde (Book of Marvels of the World), characteristics cause death with a glance, often described in French, c. 1460. Illuminated by the Master of the Geneva as a crested snake or as a rooster with a Boccaccio. France, Angers. Ink snake’s tail. Here, the basilisk appears in an and tempera on vellum. The Cryptozoology the study of hidden creatures, which aims to Morgan Library & Museum, image that is supposed to represent Ethiopia. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan prove the existence of beasts from folklore (1837–1913), 1911, MS M.461 (fol. -

Book of Barely Imagined for B 11/01/2013 10:17 Page I

Book of Barely Imagined for B 11/01/2013 10:17 Page i THE BOOK of BARELY IMAGINED BEINGS As centuries pass by, the mass of works grows endlessly, and one can foresee a time when it will be almost as difficult to educate oneself in a library, as in the universe, and almost as fast to seek a truth subsisting in nature, as lost among an immense number of books. Denis Diderot, Encyclopédie, 1755 In our gradually shrinking world, everyone is in need of all the others. We must look for man wherever we can find him. When on his way to Thebes Oedipus encountered the Sphinx, his answer to its riddle was: ‘Man’. That simple word destroyed the monster. We have many monsters to destroy. Let us think of the answer of Oedipus. George Seferis, Nobel Prize speech, 1963 Book of Barely Imagined for B 11/01/2013 10:17 Page ii Book of Barely Imagined for B 11/01/2013 10:17 Page iii THE BOOK of BARELY IMAGINED BEINGS CASPAR HENDERSON Illustrated by GOLBANOU MOGHADDAS Book of Barely Imagined for B 11/01/2013 10:17 Page iv Granta Publications, 12 Addison Avenue, London W11 4QR First published in Great Britain by Granta Books, 2012 Copyright © Caspar Henderson, 2012 Caspar Henderson has asserted his moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. The picture credits on pp. 414–5 and the text credits on pp. 416–7 constitute extensions of this copyright page. All rights reserved. -

Bestiary of Krynn, Revised

Bestiary of Krynn, Revised Designers: Cam Banks, André La Roche Additional Design: Jamie Chambers, Christopher Coyle, Sean Macdonald, Trampas Whiteman Editing: Jamie Chambers Proofreading: Elizabeth Baldwin, Christy Everette, Margaret Weis Project Manager: Jamie Chambers Typesetter: Sean Everette Art Director: Renae Chambers, Christopher Coyle Cover Artist: Jeff Easley Interior Artists: Omar Dogan, Jason Engle, Mark Evans, Eric Fortune, Scott Harshbarger, Scott Hepburn, James Holloway, Jennifer Meyer, Stanley Morrison, Ron Spencer, Eric Vedder, Brad Williams, Kevin Yan, Jim Zubkavich Cover Graphic Designer: Ken Whitman Interior Graphic Designer: Kevin T. Stein Special Thanks: Shivam Bhatt, Ross Bishop, Neil Burton, Weldon Chen, Richard Connery, Luis Fernando De Pippo, Tracy Everette, Matt Haag, Ben Jacobson, Tobin Melroy, Ashe Potter, Joshua Stewart, Heine Kim Stick This d20 System® game accessory utilizes mechanics developed for the new DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® game by Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Peter Adkison. This Wizards of the Coast® Official Licensed Product contains no Open Game Content. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form without written permission. To learn more about the Open Gaming License and the d20 System License, please visit www.wizards.com/d20. DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Dungeon Master, DRAGONLANCE, the DRAGONLANCE Logo, d20, the d20 System Logo, Wizards of the Coast, and the Wizards of the Coast Logo are registered trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, Inc., a subsidiary of Hasbro, Inc. © 2006 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Used with permission. All rights reserved. First Printing—2006. Printed in the USA. © 2006 Margaret Weis Productions, Ltd. Margaret Weis Productions and the Margaret Weis Productions Logo are trademarks owned by Margaret Weis Productions, Ltd. -

Dragon Magazine #199

Issue #199 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Vol. XVIII, No. 6 November 1993 Theres no escape from 9 New options and opportunities for DMs to torment Publisher TSR, Inc. their PCs. Opening the Book of Beasts David Howery Associate Publisher Brian Thomsen 10 Medieval bestiaries had some odd ideas about animalsideas DMs can add to their campaigns. Editor-in-Chief Kim Mohan 16 Crude, But Effective Derek Jensen Associate editor Battle tactics for humanoid monsters, courtesy of Dale A. Donovan Elmonster. Fiction editor The Dragons Bestiary: Those Terrible Trolls Barbara G. Young 23 Alec Baclawski Editorial assistant Several new types to regenerate interest in the Wolfgang H. Baur species. Art director Larry W. Smith FICTION Production staff Tracey Isler One-Eyed Death Jonathan Shipley 30 Savor this tale of honor, obligation, and assassination. Subscriptions Janet L. Winters U.S. advertising REVIEWS Cindy Rick Eye of the Monitor Sandy Petersen U.K. correspondent 56 The Day of the Tentacle has arrived! and U.K. advertising Wendy Mottaz Role-playing Reviews Rick Swan 66 The Force is stronger than ever with the Editorial Contributions STAR WARS* 2nd Edition game. Roger E. Moore Janis Wells Lisa Neuberger DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6646) is published tion throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR, Inc., P.O. Box 756 (201 Sheridan Magazine Marketing, Tavistock Road, West Drayton, Springs Road), Lake Geneva WI 53147, United States Middlesex UB7 7QE, United Kingdom; telephone: of America. The postal address for all materials from 0695-444055. the United States of America and Canada except Subscriptions: Subscription rates via second-class subscription orders is: DRAGON® Magazine, P.O. -

Representing Animals in Early Modern English Heraldry Kathryn Will [email protected]

Early Modern Culture Volume 11 Article 6 7-1-2016 When is a Panther not a Panther? Representing Animals in Early Modern English Heraldry Kathryn Will [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Will, Kathryn (2016) "When is a Panther not a Panther? Representing Animals in Early Modern English Heraldry," Early Modern Culture: Vol. 11 , Article 6. Available at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/emc/vol11/iss1/6 This Seminar Essay is brought to you for free and open access by TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Early Modern Culture by an authorized editor of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When is a Panther Not a Panther? Representing Animals in Early Modern English Heraldry KATHRYN WILL he Blazon of Gentrie, a 1586 book on heraldry written by John Ferne, uses a fictional dialogue between a herald and a knight to discuss “discourses of armes and of gentry,” including “the bearing, and blazon of cote- T armors.”1 Midway through the book, Paradinus, the herald, describes an earlier writer’s take on the meanings of certain animals that may appear on coats of arms. According to “the fragments of Iacobus Capellanus,” he observes, “the Cuckow is for ingratitude, and the Doue for thankefulnesse,” lions signify “courage, furie and rage,” and “the flye is taken for a shamelesse or impudent person.” After listing over a dozen of these symbolic creatures, however, Paradinus cautions -

GURPS Bestiary for Third Edition

G U R P S B E S T I A R Y No matter where or when your campaign is set – from prehistoric times to the jungles of modern Africa – GURPS Bestiary provides all the GURPS Basic Set, Third Edition creatures of fact and fantasy you need to bring Revised and Compendium I: your world to life. So come on – take a walk on Character Creation are required to use this book in a GURPS the wild side! campaign. GURPS Bestiary can also be used as a sourcebook for Inside this third edition, you’ll find: any roleplaying system. Complete descriptions of more than 150 real THE BEAST MASTERS: and imaginary creatures, from Antelope to Written by Water Buffalo, from Agropelter to Yeti. STEFFAN O’SULLIVAN Revised by Expanded information for creating an animal HUNTER JOHNSON character – how to build a racial template from bestiary stats and adapt the template to a Edited by MONICA STEPHENS, character for your campaign. STEVE JACKSON, Guidelines for using animals in your campaign, AND JEFF KOKE S including detailed rules for hunting and Cover by T KEN KELLY E trapping, venom, animals in combat, and V animal companions. Illustrated by E KENT BURLES, J Suggestions for inventing new creatures to keep A DAN CARROLL, C players on their toes. AND SEAN MURRAY K S A complete set of habitat tables, showing where O THIRD EDITION, FIRST PRINTING N each species is most often found and giving UBLISHED CTOBER P O 2000 G their important stats at a glance. A ISBN 1-55634-412-0 M E S ® 9!BMF@JA:RSSPQPoY`ZfZdZnZ` STEVE JACKSON GAMES Printed in the www.sjgames.com SJG01995 6011 U.S.A. -

Unicorn Modello 1

The Path of the Unicorn The Image through the Arts Catalog of the Exhibition Edited by Elisa Lanza The Path of the Unicorn. The Image through the Arts Catalog of the Exhibition 3rd of May - 31st of July 2013 St John International University Campus Art Studio Vinovo (Turin) Castello della Rovere Catalog edited by Elisa Lanza Exhibition Curators: Elisa Lanza Lindsay Wold Panel Designer: Johnny Hill Catalog Layout Editing: Alessia Fassone Elisa Lanza Panel Translation into Italian: Francesco Catalano Simona Da Ros Silvia Duchi Elisa Lanza 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS AKNOWLEDGMENTS | ELISA LANZA ........................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION | ELISA LANZA - LINDSAY WOLD ...................................................................................... 6 THE LOGO OF SJIU .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 T HE EXHIBITION ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 1 . THE COAT OF ARMS OF VINOVO | ALESSIA FASSONE .................................................................. 8 CHAPTER 2 . THE ANCIENT MOSAIC TECHNIQUE | AMBER FRAZIER ............................................................... 11 HISTORY OF THE MOSAIC ...............................................................................................................................................