Man and Beast in American Comic Legena • PART~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

Massachusetts History and Social Science Guide for Pre-Kindergarten to Grade 4

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 447 022 SO 032 239 AUTHOR Goldsmith, Susan Secor TITLE Massachusetts History and Social Science Guide for Pre-Kindergarten to Grade 4. A Model Scope and Sequence and Sample Resources. INSTITUTION Massachusetts State Dept. of Education, Boston. PUB DATE 2000-06-00 NOTE 72p.; For Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework, see SO 030 597. AVAILABLE FROM Massachusetts State Department of Education, 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5023; Tel: 781-338-3000; Web site: (http://www.doe.mass.edu). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052)-- Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; *History; Models; Preschool Education; *Public Schools; Reading Aloud to Others; *Reading Material Selection; *Social Sciences; *Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Massachusetts; *Scope and Sequence ABSTRACT This model responds to the need of many Massachusetts schools and teachers for specific guides to the required scope of core knowledge, to curriculum design, and to teaching resources. Each unit of study in the model is accompanied by a group of sample readings from children's literature, largely nonfiction selections. The model is not prescriptive, but intended solely to assist curriculum committees and teachers who want assistance in planning and carrying out engaging units of study. The model is divided into the following sections: "Introduction"; "The Scope of Introductory History Study"; "Model Scope and Sequence Overviews" ("Pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten"; -

Program Notes by MARTIN BOOKSPAN

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER March 24, 1999 8-10 PM New York City Opera: Lizzie Borden Program Notes by MARTIN BOOKSPAN "Lizzie Borden"- Music by Jack Beeson; libretto by Kenward Elmslie; based on a scenario by Richard Plant. World premiere given at New York City Opera, March 25, 1965. "Lizzie Borden took an ax, and gave her father forty whacks." This childhood rhyme may have passed from currency in the waning years of the twentieth century, but the event it memorialized was very much alive in the waning years of the nineteenth. Along with the likes of Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, Lizzie Borden of Fall River, Massachusetts, assumed legendary status in the American popular imagination. In some respects the situation seems to be a remarkable parallel to one with which we are all familiar, the O.J. Simpson affair. These are the facts: on August 4, 1892, the citizens of Fall River were shaken by the brutal murder of two of its most solid citizens, Andrew Borden and his wife, Abbie Gray Borden. The finger of suspicion soon pointed to Andrew Borden's thirty-three-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, known as Lizzie, an apparently demure and reserved gentlewoman. She testified at an inquest, but thereafter refused comment, even declining to testify in her own defense at the trial that ensued. The evidence arrayed against her seemed confused and even conflicting, and many in the community could not bring themselves to believe that she was guilty. Weak testimony in her favor was offered by her sister, Emma; in the final summation, these were the words of her chief defense attorney: "To find her guilty, you must believe she is a fiend. -

Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods

Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods by Mark L. Chance Playtesting, Help, and/or Editing by Christopher Chance, Katrina Chance, and Alexander Hay Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................3 The Hugag............................................................4 The Gumberoo....................................................5 The Roperite.........................................................6 The Snoligoster....................................................7 The Leprocaun.....................................................8 The Funeral Mountain Terrashot......................9 The Slide-Rock Bolter.......................................10 The Tote-Road Shagamaw...............................11 The Wapaloosie..................................................12 The Cactus Cat...................................................13 The Hodag..........................................................14 The Squonk.........................................................15 The Whirling Whimpus....................................16 The Agropelter...................................................17 The Splinter Cat.................................................18 The Snow Wasset...............................................19 The Central American Whintosser.................20 The Billdad..........................................................21 The Tripodero....................................................22 Slumgullion.........................................................23 Sample file -

PAUL BUNYAN TALES the QUESTION Raised by Mr

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS THE PAUL BUNYAN TALES THE QUESTION raised by Mr. Carleton C. Ames in his ar ticle on "Paul Bunyan — Myth or Hoax?," published in the March issue of this magazine, has been the subject of extensive comment in Minnesota newspapers. Among those publishing editorials on the theme are the St. Paul Pioneer Press of April 10, the Minneapolis Star-Journal of April 11, the Bemidji Daily Pioneer of April 13, the Duluth Herald of April 17, the Lake Wilson Pilot of April 18, and the Minneapolis Times-Tribune of April 19. The writers of most of these comments take the attitude that Mr. Ames is attempting to "debunk" the mythical hero of the lumber jacks; others, however, make it clear that his criticism "is not an attack on Paul but a doubt as to the age of the stories themselves." Mr. Ames restates his case In the Bemidji Pioneer of April 19, asserting that his purpose "was simply to raise the question as to whether the Paul Bunyan legend has come up out of the woods and the logging camps, or whether it has been superimposed upon them." The Pioneer Press of April 10 appeals for " evidence that stories about Bunyan were told in the period from 1860 to 1890." Something approaching such evidence Is offered by Mr. Raymond Jackson of Minneapolis in a recent letter to the editor of this magazine. He reports an interview with Mr. Fred Staples of Lakeland, the " only real lumberjack left of my acquaintance, now eighty-seven years of age." He is a son of Winslow Staples and a nephew of Isaac Staples, " two brothers who came to Minnesota from Maine to cut trees . -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

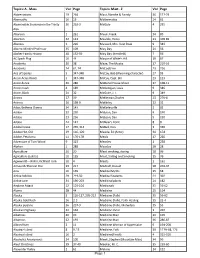

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Wisconsin Folklore and Folklife Society Which Has Excellent Promise

FOLKLORE Walker D. Wyman Acknowledgement Unive rsity of Wisconsin-Extension· is especially indebted to Dr. Loren Robin son of the Department of J ournali sm, University of Wisconsin, River Fall s, and lo Leon Zaborowski, Universit y Extension, River Falls, for the initial concept of a series of articles on Wisconsin fo lklore, published through daily and weekly newspa pe rs in Wisconsin. It was from those articles by Walker Wyman that this book was developed. The contribution of the va rious newspapers which ca rried the articles is also gratefully acknowledged. A Grass Roots Book Copyright © 1979 by Unive r sity of Wisconsin Boar d of Regents All r ight s r eserved Libra ry of Congress Catalog Ca rd Number 79-65323 Published by University of Wisconsin-Extension Department of Arts Development. Price: $4.95 ii Foreword The preparation of a book on folklore to be published by the University Exten sion is a major event. There has been, for many years, strong sentiment that the University of Wisconsi n ought to take a more dynamic interest in folklore, and that eventually, academic work in that subject should be established on many of the cam puses. So far only the Universities at Eau C laire, River Falls, and at Stevens Point have formal courses. The University at M adison has never had an y such course though informal interest has been strongly present. The University at R iver Falls has developed, through the activities and interests of Dr. Walker W yman, a publish ing program which has produced several books of regional fol klore. -

American Studies Through Folktales. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 24P.; Journal Article Offprint

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 765 SO 026 134 AUTHOR Pedersen, E. Martin TITLE American Studies through Folktales. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 24p.; Journal article offprint. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) JOURNAL CIT Messana: Rassegna Di Studi Filologici Linguistici E Storici; nll p165-185 1992 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Studies; *Folk Culture; Higher Education; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Folktales; Steinbeck (John); Twain (Mark) ABSTRACT American studies is a combination of fields such as literature, history, phinsophy, politics, and economics. This publication examines how tie different fields of study relate to American studies through folklore or folktales. The use of folktales can provide better illust-ations and understandings of U.S. individuals' heritage and evolution. Famous artists noted for using folktales to describe U.S. culture are Mark Twain and John Steinbeck. (JAG) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office ol Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES originating it. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." Qs Minor changes have been made to -----------improve reproduction quality. 0 Points of view or opinions staled in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy. VJ BEST COPY AVAILABLE % AMERICAN STUDIES THROUGH FOLK TALES' Folklore and American studies The basic social sciences, the language arts, and the fine and prac- tical arts all have aspects of similarity, and there is some overlapping among them. -

Fort Laramie Park History, 1834 – 1977

Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1977 FORT LARAMIE PARK HISTORY 1834-1977 by Merrill J. Mattes September 1980 Rocky Mountain Regional Office National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior TABLE OF CONTENTS fola/history/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Mar-2003 file:///C|/Web/FOLA/history/index.htm [9/7/2007 12:41:47 PM] Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Fort Laramie Park History, 1834-1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Author's Preface Part I. FORT LARAMIE, 1834 - 1890 I Introduction II Fur Trappers Discover the Oregon Trail III Fort William, the First Fort Laramie IV Fort John, the Second Fort Laramie V Early Migrations to Oregon and Utah VI Fort Laramie, the U.S. Army, and the Forty-Niners VII The Great California Gold Rush VIII The Indian Problem: Treaty and Massacre IX Overland Transportation and Communications X Uprising of the Sioux and Cheyenne XI Red Cloud's War XII Black Hills Gold and the Sioux Campaigns XIII The Cheyenne-Deadwood Stage Road XIV Decline and Abandonment XV Evolution of the Military Post XVI Fort Laramie as Country Village and Historic Ruin Part II. THE CRUSADE TO SAVE FORT LARAMIE I The Crusade to Save Fort Laramie Footnotes to Part II file:///C|/Web/FOLA/history/contents.htm (1 of 2) [9/7/2007 12:41:48 PM] Fort Laramie NHS: Park History Part III. THE RESTORATION OF FORT LARAMIE 1. Interim State Custodianship 1937-1938 - Greenburg, Rymill and Randels 2. Early Federal Custodianship 1938-1939 - Mattes, Canfield, Humberger and Fraser 3. -

Bugbear Distinct from Other Goblinoids, Bugbear Name Their Offspring After Any Number of Things

INTRODUCTION For some Dungeon Masters, one of the trickiest parts of running a campaign is coming up with consistent character names, especially on the fly. Every dungeon master has been in that situation at one point or another; the players have a longer conversation with Village Guard #3 than you anticipated, get invested in them, and want to know their name. This book takes that issue and extends it to some of the less common Dungeons and Dragons races which have been released through officially published material. Why Use This Book? Name generators found online are an invaluable tool for dungeon masters, but finding the right one can be very hit and miss. This book strives to have names which are consistently themed, flavorful, and able to be pronounced at a glance. Using This Book This book has two main table types to roll on: Percentile and Double-Sixty. Percentile tables contain 100 names all ready to go. Simply roll a percentile die or a pair of d10s and go to that point in the table to get your name. Double-Sixty tables have 120 entries divided into two 6x10 blocks. Each entry is one half of the name with the top block going first and the bottom block going second. Roll a d6 to determine the column and a d10 to find the row for the first half, then repeat for the second half. Finally, combine the two halves to get your name. Thank You! To everyone who bought this book, told their friends, or shared it with someone, your support is encouraging me to make bigger and better projects! Thank you! ~J.L. -

English As a Second Language Podcast ENGLISH CAFÉ – 546 TOPICS Paul Bunyan; American Songs – “You're the Top”; Big Ve

English as a Second Language Podcast www.eslpod.com ENGLISH CAFÉ – 546 TOPICS Paul Bunyan; American Songs – “You’re the Top”; big versus huge versus massive; at all and show off; to be beside (oneself) _____________ GLOSSARY legend – a story from the past that many people know and repeat but that may not be true, usually of an amazing person or event * There is a legend about a ship carrying millions of gold coins which sank in the Caribbean Ocean over two hundred years ago. axe – a tool with a wooden handle and a heavy metal blade that is used for chopping wood * The firefighter swung his axe to chop down the door of the burning building to save the trapped people inside. lumberjack – a person whose job is to cut down trees that are used in building * The lumberjacks worked in teams in the woods to fell trees. canyon – a deep valley (low area between mountains) with steep and rocky sides, often with a river at the bottom * It would take a hiker several days to hike to the bottom of this canyon. hero – a person who is admired for his or her bravery or important actions * In our community, we are surrounded by real-life heroes who risk their own lives for other people, but who are unrecognized. mainstream – ideas, views, and activities that are considered normal or shared by most people * Names like Ethel and Bertha used to be considered mainstream in the U.S. but are not popular today. chopping block – a hard, usually round, piece of wood on which things such as meat, vegetables, or wood are cut * The chef put the large piece of meat on the chopping block and carefully cut it into thin steaks. -

Library Weeding Log Wiley Elementary School From: 1/7/2019 To: 4/29/2019

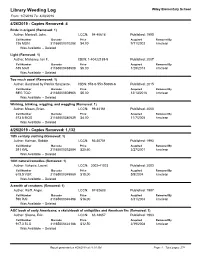

Library Weeding Log Wiley Elementary School From: 1/7/2019 To: 4/29/2019 4/26/2019 - Copies Removed: 4 Birds in origami (Removed: 1) Author: Montroll, John. LCCN: 94-40618 Published: 1995 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 736 MON 31165000310288 $4.00 9/11/2002 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted Light (Removed: 1) Author: Mahaney, Ian F. ISBN: 1-40422185-9 Published: 2007 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 535 MAH 31165000468508 $5.00 1/28/2013 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted Too much ooze! (Removed: 1) Author: illustrated by Patrick Spaziante. ISBN: 978-0-553-50866-6 Published: 2015 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By BEG TOO 31165000508956 $5.00 12/13/2016 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted Winking, blinking, wiggling, and waggling (Removed: 1) Author: Moses, Brian. LCCN: 99-44161 Published: 2000 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 573.8 MOS 31165000380539 $4.00 11/7/2005 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted 4/25/2019 - Copies Removed: 1,132 18th century clothing (Removed: 1) Author: Kalman, Bobbie. LCCN: 93-30701 Published: 1993 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 391 KAL 31165000352884 $20.60 3/27/2001 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted 1001 natural remedies (Removed: 1) Author: Vukovic, Laurel. LCCN: 2002-41023 Published: 2003 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 615.5 VUK 31165000349989 $15.00 5/5/2004 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted A-zenith of creatures (Removed: 1) Author: Raiff, Angie. LCCN: 97-92688 Published: 1997 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 590 RAI 31165000346498 $16.00 3/31/2004 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted ABC book of early Americana; a sketchbook of antiquities and American firs (Removed: 1) Author: Sloane, Eric.