Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods

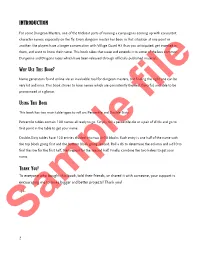

Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods by Mark L. Chance Playtesting, Help, and/or Editing by Christopher Chance, Katrina Chance, and Alexander Hay Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................3 The Hugag............................................................4 The Gumberoo....................................................5 The Roperite.........................................................6 The Snoligoster....................................................7 The Leprocaun.....................................................8 The Funeral Mountain Terrashot......................9 The Slide-Rock Bolter.......................................10 The Tote-Road Shagamaw...............................11 The Wapaloosie..................................................12 The Cactus Cat...................................................13 The Hodag..........................................................14 The Squonk.........................................................15 The Whirling Whimpus....................................16 The Agropelter...................................................17 The Splinter Cat.................................................18 The Snow Wasset...............................................19 The Central American Whintosser.................20 The Billdad..........................................................21 The Tripodero....................................................22 Slumgullion.........................................................23 Sample file -

California Folklore Miscellany Index

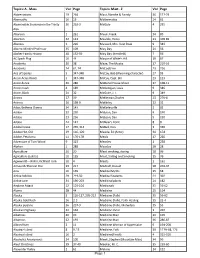

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Wisconsin Folklore and Folklife Society Which Has Excellent Promise

FOLKLORE Walker D. Wyman Acknowledgement Unive rsity of Wisconsin-Extension· is especially indebted to Dr. Loren Robin son of the Department of J ournali sm, University of Wisconsin, River Fall s, and lo Leon Zaborowski, Universit y Extension, River Falls, for the initial concept of a series of articles on Wisconsin fo lklore, published through daily and weekly newspa pe rs in Wisconsin. It was from those articles by Walker Wyman that this book was developed. The contribution of the va rious newspapers which ca rried the articles is also gratefully acknowledged. A Grass Roots Book Copyright © 1979 by Unive r sity of Wisconsin Boar d of Regents All r ight s r eserved Libra ry of Congress Catalog Ca rd Number 79-65323 Published by University of Wisconsin-Extension Department of Arts Development. Price: $4.95 ii Foreword The preparation of a book on folklore to be published by the University Exten sion is a major event. There has been, for many years, strong sentiment that the University of Wisconsi n ought to take a more dynamic interest in folklore, and that eventually, academic work in that subject should be established on many of the cam puses. So far only the Universities at Eau C laire, River Falls, and at Stevens Point have formal courses. The University at M adison has never had an y such course though informal interest has been strongly present. The University at R iver Falls has developed, through the activities and interests of Dr. Walker W yman, a publish ing program which has produced several books of regional fol klore. -

Bugbear Distinct from Other Goblinoids, Bugbear Name Their Offspring After Any Number of Things

INTRODUCTION For some Dungeon Masters, one of the trickiest parts of running a campaign is coming up with consistent character names, especially on the fly. Every dungeon master has been in that situation at one point or another; the players have a longer conversation with Village Guard #3 than you anticipated, get invested in them, and want to know their name. This book takes that issue and extends it to some of the less common Dungeons and Dragons races which have been released through officially published material. Why Use This Book? Name generators found online are an invaluable tool for dungeon masters, but finding the right one can be very hit and miss. This book strives to have names which are consistently themed, flavorful, and able to be pronounced at a glance. Using This Book This book has two main table types to roll on: Percentile and Double-Sixty. Percentile tables contain 100 names all ready to go. Simply roll a percentile die or a pair of d10s and go to that point in the table to get your name. Double-Sixty tables have 120 entries divided into two 6x10 blocks. Each entry is one half of the name with the top block going first and the bottom block going second. Roll a d6 to determine the column and a d10 to find the row for the first half, then repeat for the second half. Finally, combine the two halves to get your name. Thank You! To everyone who bought this book, told their friends, or shared it with someone, your support is encouraging me to make bigger and better projects! Thank you! ~J.L. -

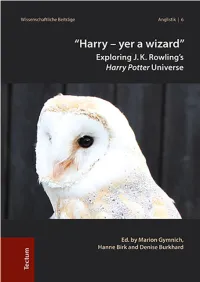

“Harry – Yer a Wizard” Exploring J

Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus dem Tectum Verlag Reihe Anglistik Band 6 Marion Gymnich | Hanne Birk | Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Tectum Verlag Marion Gymnich, Hanne Birk and Denise Burkhard (Eds.) “Harry – yer a wizard” Exploring J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter Universe Wissenschaftliche Beiträge aus demT ectum Verlag, Reihe: Anglistik; Bd. 6 © Tectum Verlag – ein Verlag in der Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2017 ISBN: 978-3-8288-6751-2 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Werk unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-4035-5 und als ePub unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-6752-9 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) ISSN: 1861-6859 Umschlaggestaltung: Tectum Verlag, unter Verwendung zweier Fotografien von Schleiereule Merlin und Janna Weinsch, aufgenommen in der Falknerei Pierre Schmidt (Erftstadt/Gymnicher Mühle) | © Denise Burkhard Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm finden Sie unter www.tectum-verlag.de Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available online at http://dnb.ddb.de. Contents Hanne Birk, Denise Burkhard and Marion Gymnich ‘Happy Birthday, Harry!’: Celebrating the Success of the Harry Potter Phenomenon ........ 7 Marion Gymnich and Klaus Scheunemann The ‘Harry Potter Phenomenon’: Forms of World Building in the Novels, the Translations, the Film Series and the Fandom ................................................................. 11 Part I: The Harry Potter Series and its Sources Laura Hartmann The Black Dog and the Boggart: Fantastic Beasts in Joanne K. -

Doc Brewer, Brewer's Backwoods

BREWER’S BACKWOODS Fearsome critters, strange flora, and fabled treasures lie beyond Fort Brewer A one-page wilderness adventure created by Doc Brewer MAP KEY (1 HEX = 10 MILES) 0100: A baneful aura lingers in this comet blast zone 0913: Fort Brewer, plus respectable New Town, seedy Old Town 0112: Enclave of druids—will they help you, or sacrifice you? 1001: An ancient evil dwells in the bottomless pool 0204: Nesting grounds of the fearsome Hodag; eggs are priceless 1006: Nocturnal horned-folk stalk these dense, dark woods 0209: Island of cursed souls who rise after nightfall 1110: Sinkholes dot the landscape; some are inhabited 0210: Dryad grove; rare and precious wood is a lure to loggers 1209: Whispers echo up and down natural limestone caves 0307: A Lorelei sings from atop a rock to enchant passersby 1212: Wellman’s Wade: crossing, trading post and gathering place 0312: Standing stone circle acts as a gate, but the secret is lost 1306: Limestone cave system leads to inky river underground 0403: What lurks behind the mists of the weird waterfall? 1313: The moonshiners in these hollows value their privacy 0509: Silver mine abandoned after too many men went missing 1404: Standing stone circle; the other end of the gate in 0312 0511: Lumberton, last outpost of loggers and hunters 1411: Reward to be had for rooting out river reavers’s roost 0513: Two clans of witches have feuded here for generations 1508: When the Pineys come out of their hiding holes, it’s too late 0606: Hidebehind that hunts here is the last thing you’ll never see 1601: -

2017 Iron Butt Rally, Leg 1 Minneapolis, MN to Allen, TX

2017 Iron Butt Rally, Leg 1 Minneapolis, MN to Allen, TX Packing List Leg 1 Bonus Pack – Minneapolis, MN to Allen, TX Claimed Bonuses Form Ask Rallymaster if there are any changes or corrections Before leaving the checkpoint, make sure you can find each bonus location and have a clear understanding of what is required to earn the bonus WARNING: DO NOT LEAVE ON A LEG UNTIL YOU HAVE VERIFIED THAT ALL PAPERWORK IS IN YOUR RALLY PACKAGE FOR THAT LEG. EACH PAGE IS NUMBERED. THIS IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY. CRITICAL: Please be respectful when placing your flag in photos. Private property and priceless museum pieces must not be used as your flag support. To earn any bonus, you MUST claim it on the Claimed Bonuses form. This includes Rest bonuses and Call-In bonuses. If you lose the Claimed Bonuses form, you will earn no bonus points for the leg. REMEMBER: Unless otherwise specified, I.D. Flags are required in all photos. Page 1 of 12 Scoring Instructions All bonuses are available at point values listed in this pack within the time restrictions listed in the rally book. Bonuses in the rally book are divided into five categories: Air, Land, Mythical, Prehistoric, and Water. Those categories are denoted in the bonus codes by the first letter of the code. For example, the “A” in code “ABB” indicates this as an “Air” bonus. Riders who successfully visit and claim three (3) bonuses in a row of the same category will earn double (2x) the listed value of the third bonus in that string of three. -

Table of Contents

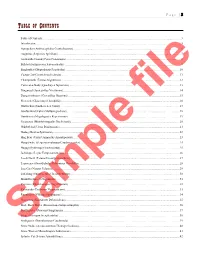

P a g e | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Agropelter (Anthrocephalus Craniofractens) ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Augerino (Serpentes Spirillum) ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Axehandle Hound (Canis Consumens).......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Billdad (Saltipiscator Falcorostratus) ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 Bingbuffer (Glyptodontis Petrobolus) ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Cactus Cat (Cactifelinus Inebrius).............................................................................................................................................................. -

1. American Folklore Creatures

1. American Folklore Creatures 1 1. Abbagoochie >The abbagoochie (pronounced abba-GOO-cheez) is a fierce little creature resembling a cross between an owl, a fox, and a deer. It is indigenous to Costa Rica, where people refer to it as a "dryland piranha" because it will eat anything, including creatures far larger than itself such as horses and cows. If cornered, an abbagoochie will consume itself "in a devilish whirlwind" rather than allow itself to be captured. They mate only once every 6 ½ years. 2. The Alkali Monster >This gargantuan, mono-horned, foul smelling, reptilian beast is reputed to lurk in the depths of Nebraska’s famed Alkali Lake, devouring all who come near it. Located in central Nebraska, Walgren Lake (formerly known as Alkali Lake) is an eroded volcanic outcropping that is reputed to be the nesting place of one of the most unusual lake monsters ever recorded and, if the legends are true, the habitat of the only aquatic monster ever reported in the state of Nebraska. Originally chronicled in Native American folklore, this creature has been described as a gargantuan alligator-like beast with some unique attributes. Eyewitnesses claim that the beast is approximately 40-feet long, with rough, grayish-brown skin and a horny outgrowth located between its eyes and nostrils. 3. The Altamaha-ha >Local legend reports a 20-foot-long water serpent that dwarfs the size of alligators in the region. It lives where the Altahama River dumps into the Atlantic Ocean, and thus a host of very real sea creatures have been suggested as explanations for the beast. -

LA CHASSE AU SQUONK Épopée Folk Et Humour Sauvage a Partir De 7 Ans – 80 Min

LA CHASSE AU SQUONK Épopée folk et humour sauvage A partir de 7 ans – 80 min. Gabriel Zegna Photographies Frédéric Duvaud et Julien Rambaud Duo « La truite a fourrure » www.latruiteafourrure.fr [email protected] port. : 06 86 89 14 83 LA CHASSE AU SQUONK Épopée folk et humour sauvage Épopée Nord-Américaine a partir de 7 ans - Durée : 80 min. Duo « la truite a Fourrure » Fred Duvaud et Jul Rambaud. Photo : Paola Guigou Un crapaud, c'est moche. Mais un crapaud ne sait pas qu’il l'est. Le squonk n’a pas cette chance. Lui, il sait qu'il est laid et ca le rend tres triste. Attendez... Vous ne connaissez pas le squonk ? A vrai dire, nous non plus, enfin on ne l’a jamais vraiment vu. Mais parfois, la nuit, au fond des bois de Pennsylvanie, Etats-unis, on peut l’entendre pleurer... Et quand il pleure, il laisse des flaques d'eau, comme des traces. Alors partons a la chasse ! Prenons nos grosses bottes et surtout ouvrons nos oreilles. C’est que dans cette foret americaine, d'autres bestioles rodent : le chat- cactus, le mange-manche, la truite a fourrure, le lapin a cornes, sans oublier le terrible "Hide-Behind", que personne n'a jamais vu car il est toujours cache dans le dos des gens. Mais la plus terrible des créatures, c'est sur, ca reste le bucheron. Fred Duvaud est conteur et slameur, Julien Rambaud est guitariste et chanteur. Tous deux partagent un même goût pour la musique américaine et son folklore. Ensemble, ils vous invitent à explorer, dans une embardée musicale country, folk et hip-hop, la faune sauvagement drôle des récits de trappeurs et bûcherons de l'Amérique du nord. -

America's Fearsome Creatures

America’s Fearsome Creatures By Aoty 1 43. A Composite Monster 1. The Abbagoochie 44. Commodore Preble’s Monster 2. The Alkali Monster 45. The Cougar Fish 3. The Altamaha-ha 46. The Cuba 4. Amhuluk 47. The Devil-Jack Diamond Fish 5. Angont 48. The Dewayo 6. Apotamkin 49. The Dew Mink 7. The Argopelter 50. The Ding-ball 8. The Arkansas Snipe 51. The Dingbat 9. The Augerino 52. The Double Rat 10. The Axehandle Hound 53. The Dubuque Monster Reptile 11. The Backus Monster 54. The Duck-Footed Dum DUm 12. The Balloon Fish 55. The Dungavenhooter 13. The Bassigator 56. The Fire-Starter Beast 14. The Bear Lake Monster 57. The Fish-Fox 15. The Beazel 58. The Fish-Hound 16. The Bildad 59. The Flittericks 17. The Biloxi Bay Devil Fish 60. The Flying Serpents 18. The Bird of Winnemucca 61. The Funeral Mountain Terrashot 19. The Black Dog 62. The Gaasyendietha 20. The Black Newfoundland DOg 63. The Galliwampus 21. The Black Hodag 64. The Gallywampus 22. The Black Fox of Salmon River 65. The Gazerium and Snydae 23. The Boat Hound 66. The Gazunk, or The Flute Bill 24. The Bone-Headed Penguin 67. The Godaphro 25. The Booger Dog 68. The Golden Bears 26. The Boont 69. The Gollywog 27. The Brazilian Trench Digger 70. The Goofang 28. The Bright Old Inhabitants 71. The Goofus Bird 29. The Bull of Durham 72. The Giant Lobster 30. The Cactus Cat 73. The Giddy Fish 31. Caldera Dick 74. The Gigantic Feathered Creature 32.