A Review of Primary Vasculitis Mimickers Based on the Chapel Hill Consensus Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Known Infectious Causes of Vasculitis in Man

PATHOGENESIS Known infectious causes of vasculitis in man STANLEY J. NAIDES, MD n array of pathogens is known to cause vasculi- and our ability to intervene in disease processes, have ren- tis in man.1,2 For several of these agents, vas- dered some causes of vasculitis far less common. culitis is the major manifestation of disease. The Amajority, however, typically present as infec- ■ VIRAL CAUSES OF VASCULITIS tious processes in which vasculitis is an occasional mani- Our knowledge of viral pathogenesis has exploded in the festation of disease. For many, vasculitis may be a compo- last quarter of the twentieth century, accelerated in large nent of disease pathogenesis but is not a prominent feature part by epidemics of “emerging” viral diseases. Hepatitis C of the clinical presentation. The various agents—viruses, virus, discovered in 1989, has worldwide prevalence.3 The bacteria, and fungi—share a common target, blood vessels. 10- to 20-year latent period before hepatic or rheumatic The involvement of vessels may be direct, with vascular manifestations of disease explains the increasing number structures serving as targets. Many infectious pathogens of cases of hepatitis C virus–mediated vasculitis currently have tissue tropism that includes endothelium. Other being seen in the United States following the epidemic of agents may bind to the vessel wall because the vascular en- new infections in the 1980s.4 Prior to the discovery and dothelium expresses specific receptors for the pathogen or characterization of hepatitis C virus in the late 1980s, the another moiety with which the pathogen travels. Even triad of arthritis, palpable purpura, and type II cryoglobu- when the agent does not enter the endothelial cell, the im- linemia was given the sobriquet “essential mixed cryo- mune response to the agent may be focused at the vessel globulinemia” and considered an idiopathic vasculitis. -

Identification of Microorganisms Using Nucleic Acid Probes

Identification of Microorganisms Using Page 1 of 45 Nucleic Acid Probes Medical Policy An Independent Licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association Title: Identification of Microorganisms Using Nucleic Acid Probes See Also: Influenza Virus Diagnostic Testing and Treatment in the Outpatient Setting Professional Institutional Original Effective Date: July 8, 2008 Original Effective Date: July 16, 2009 Revision Date(s): June 16, 2009; Revision Date(s): March 1, 2012; March 1, 2012; June 5, 2012; June 5, 2012; November 19, 2012; November 19, 2012; January 15, 2013; January 15, 2013; November 12, 2013 November 12, 2013 Current Effective Date: November 12, 2013 Current Effective Date: November 12, 2013 State and Federal mandates and health plan member contract language, including specific provisions/exclusions, take precedence over Medical Policy and must be considered first in determining eligibility for coverage. To verify a member's benefits, contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Customer Service. The BCBSKS Medical Policies contained herein are for informational purposes and apply only to members who have health insurance through BCBSKS or who are covered by a self-insured group plan administered by BCBSKS. Medical Policy for FEP members is subject to FEP medical policy which may differ from BCBSKS Medical Policy. The medical policies do not constitute medical advice or medical care. Treating health care providers are independent contractors and are neither employees nor agents of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas and are solely responsible for diagnosis, treatment and medical advice. If your patient is covered under a different Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan, please refer to the Medical Policies of that plan. -

Syphilis As Seen by a Hospital Physician

284 Prof. Monro?Syphilis as seen by a Hospital Physician. SYPHILIS AS SEEN BY A HOSPITAL PHYSICIAN* By T. K. MONRO, M.A., M.D., Professor of Medicine, University of Glasgow. \ " / Mr. President and Gentlemen,?I thank you heartily for the honour you have done me in inviting me to be Honorary President of this Faculty for the session which is now opening. I was duly informed by Dr. Wardlaw that my principal duty as incumbent of this honourable office was to deliver an address to the Faculty, and as his invitation reached me while I was on holiday, with other objects in view, I had time to contemplate the responsibility I had undertaken, and to consider how I was to face it. In getting over the usual initial difficulty as to the choice of a subject, some assistance was afforded me by the President's instruction that the address ought to be one for the general practitioner. Quite a number of subjects would be appropriate from this point of view. I should have been glad to say some- thing on oral sepsis, a condition often spoken of, and no doubt often wrongly blamed, but also apt to be overlooked. Dentists do not always realise how completely one may be misled by the absence of subjective and objective evidence; so that even an experienced man may pass as innocuous a tooth which subse- quent extraction shows to have disease at its root. Medical men sometimes make a mistake in the opposite direction, by insisting, without sufficient justification, on the removal of teeth, e.g., in epileptiform neuralgia. -

ANCA--Associated Small-Vessel Vasculitis

ANCA–Associated Small-Vessel Vasculitis ISHAK A. MANSI, M.D., PH.D., ADRIANA OPRAN, M.D., and FRED ROSNER, M.D. Mount Sinai Services at Queens Hospital Center, Jamaica, New York and the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)–associated vasculitis is the most common primary sys- temic small-vessel vasculitis to occur in adults. Although the etiology is not always known, the inci- dence of vasculitis is increasing, and the diagnosis and management of patients may be challenging because of its relative infrequency, changing nomenclature, and variability of clinical expression. Advances in clinical management have been achieved during the past few years, and many ongoing studies are pending. Vasculitis may affect the large, medium, or small blood vessels. Small-vessel vas- culitis may be further classified as ANCA-associated or non-ANCA–associated vasculitis. ANCA–asso- ciated small-vessel vasculitis includes microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg- Strauss syndrome, and drug-induced vasculitis. Better definition criteria and advancement in the technologies make these diagnoses increasingly common. Features that may aid in defining the spe- cific type of vasculitic disorder include the type of organ involvement, presence and type of ANCA (myeloperoxidase–ANCA or proteinase 3–ANCA), presence of serum cryoglobulins, and the presence of evidence for granulomatous inflammation. Family physicians should be familiar with this group of vasculitic disorders to reach a prompt diagnosis and initiate treatment to prevent end-organ dam- age. Treatment usually includes corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy. (Am Fam Physician 2002;65:1615-20. Copyright© 2002 American Academy of Family Physicians.) asculitis is a process caused These antibodies can be detected with indi- by inflammation of blood rect immunofluorescence microscopy. -

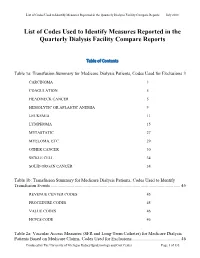

List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the QDFC

List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports July 2018 List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports Table of Contents Table 1a: Transfusion Summary for Medicare Dialysis Patients, Codes Used for Exclusions 3 CARCINOMA 3 COAGULATION 5 HEAD/NECK CANCER 5 HEMOLYTIC OR APLASTIC ANEMIA 9 LEUKEMIA 11 LYMPHOMA 15 METASTATIC 27 MYELOMA, ETC. 29 OTHER CANCER 30 SICKLE CELL 34 SOLID ORGAN CANCER 34 Table 1b: Transfusion Summary for Medicare Dialysis Patients, Codes Used to Identify Transfusion Events .................................................................................................................. 45 REVENUE CENTER CODES 45 PROCEDURE CODES 45 VALUE CODES 46 HCPCS CODE 46 Table 2a: Vascular Access Measures (SFR and Long-Term Catheter) for Medicare Dialysis Patients Based on Medicare Claims, Codes Used for Exclusions ........................................... 46 Produced by The University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center Page 1 of 135 List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports July 2018 COMA 46 END STAGE LIVER DISEASE 48 METASTATIC CANCER 48 Table 2b: Standardized Fistulae Rate (SFR) for Medicare Dialysis Patients Based on Medicare Claims, Codes Used for Prevalent Comorbidities Adjusted in Model .................................... 50 ANEMIA 50 CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE 52 CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE 55 CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE 56 CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE 68 DIABETES 69 DRUG DEPENDENCE 79 INFECTIONS (NON-VASCULAR ACCESS-RELATED): 93 PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE (INCLUDES ARTERIAL, VENOUS AND NONSPECIFIC DISEASES) 124 Table 3: Dialysis Adequacy ................................................................................................... -

Rheumatology 2 Objectives

1 RHEUMATOLOGY 2 OBJECTIVES Know and understand: • How the clinical presentations of rheumatologic diseases can vary • Components of a thorough physical examination for investigating rheumatoid complaints • How to differentiate between different rheumatologic diseases • Evidence-based management of rheumatologic diseases 3 TOPICS COVERED • Osteoarthritis • Rheumatoid Arthritis • Gout • Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease • Polymyalgia Rheumatica • Giant Cell Arteritis (Temporal Arteritis) • Systemic Lupus Erythematosus • Sjögren Syndrome • Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis • Fibromyalgia 4 OSTEOARTHRITIS (OA): OVERVIEW • Principal cause of knee, hip, and back pain in older adults, and most common source of chronic pain • Avoid the reflexive conclusion that all joint pain in older adults is the result of OA • Can develop in any joint that has suffered injury or other disease • Hallmark: cartilage degeneration Ø But not purely a degenerative disease; subchondral bone abnormalities and focal synovial inflammation are also seen in pathologic specimens 5 OA: DIAGNOSIS • Differential diagnosis: inflammatory and crystal arthritides, septic arthritis, bone pain due to malignancy • Bony enlargement and crepitus suggest OA Ø In the fingers, bony enlargement occurs in the distal interphalangeal joint (Heberden nodes) and in the proximal interphalangeal joints (Bouchard nodes) Ø Osteophytes are the radiographic counterpart of this enlargement, and asymmetric joint space narrowing is common • Joint tenderness and warmth may appear, but true synovitis -

Lecture 1 ― INTRODUCTION INTO MICROBIOLOGY

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ БЕЛАРУСЬ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ «ГОМЕЛЬСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ» Кафедра микробиологии, вирусологии и иммунологии А. И. КОЗЛОВА, Д. В. ТАПАЛЬСКИЙ МИКРОБИОЛОГИЯ, ВИРУСОЛОГИЯ И ИММУНОЛОГИЯ Учебно-методическое пособие для студентов 2 и 3 курсов факультета по подготовке специалистов для зарубежных стран медицинских вузов MICROBIOLOGY, VIROLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY Teaching workbook for 2 and 3 year students of the Faculty on preparation of experts for foreign countries of medical higher educational institutions Гомель ГомГМУ 2015 УДК 579+578+612.017.1(072)=111 ББК 28.4+28.3+28.073(2Англ)я73 К 59 Рецензенты: доктор медицинских наук, профессор, заведующий кафедрой клинической микробиологии Витебского государственного ордена Дружбы народов медицинского университета И. И. Генералов; кандидат медицинских наук, доцент, доцент кафедры эпидемиологии и микробиологии Белорусской медицинской академии последипломного образования О. В. Тонко Козлова, А. И. К 59 Микробиология, вирусология и иммунология: учеб.-метод. пособие для студентов 2 и 3 курсов факультета по подготовке специалистов для зарубежных стран медицинских вузов = Microbiology, virology and immunology: teaching workbook for 2 and 3 year students of the Faculty on preparation of experts for foreign countries of medical higher educa- tional institutions / А. И. Козлова, Д. В. Тапальский. — Гомель: Гом- ГМУ, 2015. — 240 с. ISBN 978-985-506-698-0 В учебно-методическом пособии представлены тезисы лекций по микробиоло- гии, вирусологии и иммунологии, рассмотрены вопросы морфологии, физиологии и генетики микроорганизмов, приведены сведения об общих механизмах функциони- рования системы иммунитета и современных иммунологических методах диагности- ки инфекционных и неинфекционных заболеваний. Приведены сведения об этиоло- гии, патогенезе, микробиологической диагностике и профилактике основных бакте- риальных и вирусных инфекционных заболеваний человека. Может быть использовано для закрепления материала, изученного в курсе микро- биологии, вирусологии, иммунологии. -

Guideline-Management-Giant-Cell

Arthritis Care & Research Vol. 73, No. 8, August 2021, pp 1071–1087 DOI 10.1002/acr.24632 © 2021 American College of Rheumatology. This article has been contributed to by US Government employees and their work is in the public domain in the USA. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Giant Cell Arteritis and Takayasu Arteritis Mehrdad Maz,1 Sharon A. Chung,2 Andy Abril,3 Carol A. Langford,4 Mark Gorelik,5 Gordon Guyatt,6 Amy M. Archer,7 Doyt L. Conn,8 Kathy A. Full,9 Peter C. Grayson,10 Maria F. Ibarra,11 Lisa F. Imundo,5 Susan Kim,2 Peter A. Merkel,12 Rennie L. Rhee,12 Philip Seo,13 John H. Stone,14 Sangeeta Sule,15 Robert P. Sundel,16 Omar I. Vitobaldi,17 Ann Warner,18 Kevin Byram,19 Anisha B. Dua,7 Nedaa Husainat,20 Karen E. James,21 Mohamad A. Kalot,22 Yih Chang Lin,23 Jason M. Springer,1 Marat Turgunbaev,24 Alexandra Villa-Forte, 4 Amy S. Turner,24 and Reem A. Mustafa25 Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particu- lar patient. The ACR considers adherence to the recommendations within this guideline to be voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding their application to be made by the physician in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are intended to promote beneficial or desirable outcomes but cannot guarantee any specific outcome. -

PMR) / Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA

Arthritis and Rheumatology Clinics of Kansas Patient Education Polymyalgic Rheumatica (PMR) / Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) Introduction: PMR and GCA are related conditions affecting adults over the age of 50. Both are inflammatory diseases, with PMR involving the large joints of the hips and/or shoulders and GCA involving large and medium sized blood vessels. PMR occurs in about 30 individuals over the age of 50 per 100,000 population per year, while GCA is roughly half as common. Both conditions are about twice as common in women as in men and are seen most commonly in those of Northern European descent. The average age of onset is about 70 for both conditions, and with the aging population the prevalence of these disorders is expected to increase in the next few decades. While the cause of these conditions is unknown, the fact that they tend to occur in cooler climates and in clusters of cases every several years suggests that infections may trigger PMR and GCA. Having certain genes also seems to increase the risk of developing either of these disorders. Features of PMR: Patients with PMR tend to experience widespread pain in the regions of the shoulders, upper arms, neck, hips, buttock, and thighs. These symptoms may be sudden in onset and are accompanied by up to several hours of morning stiffness. While swelling of knees, elbows, or wrists may occur, there is most often no visible joint swelling but only difficulty with movement of the larger joints. A small percentage of patients may experience swelling of the entire hand and foot with edema, or excess fluid accumulation. -

Tabes Dorsalis and Perforated Duodenal Ulcer J

i6o Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.37.425.160 on 1 March 1961. Downloaded from POSTGRAD. MED. J. (1961), 37, i60 TABES DORSALIS AND PERFORATED DUODENAL ULCER J. P. LAWSON, M.B., Ch.B. Late Senior House Officer in Medicine, Crumpsall Hospital, Manchester Senior House Oficer in Radiology, David Lewis Northern Hospital, Liverpool 3 IT is well recorded that tabes dorsalis can mask between the shoulder blades whilst standing in a bus serious visceral disease. Wilson mentions queue. This was shortly followed by a bout of vomiting (1954) and sweating. There was no dyspncea, pain in the chest that tabes can disrupt nervous pathways so as to or abdominal pain. The patient was able to make his produce a visceral analgesia capable of masking own way home on foot. serious abdominal disease. At home he took a Sedlitz powder, which was followed by three further attacks of vomiting and four Connor (I91o) published a case of a brakeman, loose bowel actions. There was no blood in either aged 42, who died in hospital following an acute vomitus or faeces. The pain spread to both shoulder febrile attack and vomiting. There had been no tips, where it persisted and was the cause of his attend- abdominal tenderness or to ance at the casualty department. pain, rigidity explain Four years previously he had developed a similar the condition but autopsy revealed a perforated attack of sweating and stated that he had also vomited appendix abscess and peritonitis. blood. At this time he was apparently found to be from and was trans- Hanser (I9I9) recorded the case of a tabetic suffering pulmonary tuberculosis, by copyright. -

Diagnosis One To

Diagnosis One-to-One I9cm I9 Long Desc I10cm I10 Long Desc 0010 Cholera due to vibrio cholerae A000 Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar cholerae 0011 Cholera due to vibrio cholerae el tor A001 Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar eltor 0019 Cholera, unspecified A009 Cholera, unspecified 0021 Paratyphoid fever A A011 Paratyphoid fever A 0022 Paratyphoid fever B A012 Paratyphoid fever B 0023 Paratyphoid fever C A013 Paratyphoid fever C 0029 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified A014 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified 0030 Salmonella gastroenteritis A020 Salmonella enteritis 0031 Salmonella septicemia A021 Salmonella sepsis 00320 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified A0220 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified 00321 Salmonella meningitis A0221 Salmonella meningitis 00322 Salmonella pneumonia A0222 Salmonella pneumonia 00323 Salmonella arthritis A0223 Salmonella arthritis 00324 Salmonella osteomyelitis A0224 Salmonella osteomyelitis 0038 Other specified salmonella infections A028 Other specified salmonella infections 0039 Salmonella infection, unspecified A029 Salmonella infection, unspecified 0040 Shigella dysenteriae A030 Shigellosis due to Shigella dysenteriae 0041 Shigella flexneri A031 Shigellosis due to Shigella flexneri 0042 Shigella boydii A032 Shigellosis due to Shigella boydii 0043 Shigella sonnei A033 Shigellosis due to Shigella sonnei 0048 Other specified shigella infections A038 Other shigellosis 0049 Shigellosis, unspecified A039 Shigellosis, unspecified 0050 Staphylococcal food poisoning A050 Foodborne staphylococcal -

BQI Icare HIV/AIDS

RESOURCE AND PATIENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM iCare Population Management GUI (BQI) HIV/AIDS Management User Manual Version 2.6 July 2017 Office of Information Technology (OIT) Division of Information Technology iCare Population Management GUI (BQI) Version 2.6 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Key Functional Features .......................................................................... 1 1.2 Sensitive Patient Data ............................................................................. 2 2.0 Patient Management ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 Data Specifically Related to HIV/AIDS ..................................................... 3 2.2 Search for and View a Patient Record ..................................................... 6 2.2.1 Using a Panel ........................................................................................ 6 2.2.2 Using Quick Search ............................................................................... 7 2.3 Displaying Care Management as Default Tab ......................................... 8 2.4 Add/Edit Care Management Data ............................................................ 8 2.4.1 Entering Data on the General Area ....................................................... 9 2.4.2 Entering Data on the Partner Notification Area .................................... 11 2.4.3 Entering Data on the Antiretroviral