Syphilis As Seen by a Hospital Physician

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Known Infectious Causes of Vasculitis in Man

PATHOGENESIS Known infectious causes of vasculitis in man STANLEY J. NAIDES, MD n array of pathogens is known to cause vasculi- and our ability to intervene in disease processes, have ren- tis in man.1,2 For several of these agents, vas- dered some causes of vasculitis far less common. culitis is the major manifestation of disease. The Amajority, however, typically present as infec- ■ VIRAL CAUSES OF VASCULITIS tious processes in which vasculitis is an occasional mani- Our knowledge of viral pathogenesis has exploded in the festation of disease. For many, vasculitis may be a compo- last quarter of the twentieth century, accelerated in large nent of disease pathogenesis but is not a prominent feature part by epidemics of “emerging” viral diseases. Hepatitis C of the clinical presentation. The various agents—viruses, virus, discovered in 1989, has worldwide prevalence.3 The bacteria, and fungi—share a common target, blood vessels. 10- to 20-year latent period before hepatic or rheumatic The involvement of vessels may be direct, with vascular manifestations of disease explains the increasing number structures serving as targets. Many infectious pathogens of cases of hepatitis C virus–mediated vasculitis currently have tissue tropism that includes endothelium. Other being seen in the United States following the epidemic of agents may bind to the vessel wall because the vascular en- new infections in the 1980s.4 Prior to the discovery and dothelium expresses specific receptors for the pathogen or characterization of hepatitis C virus in the late 1980s, the another moiety with which the pathogen travels. Even triad of arthritis, palpable purpura, and type II cryoglobu- when the agent does not enter the endothelial cell, the im- linemia was given the sobriquet “essential mixed cryo- mune response to the agent may be focused at the vessel globulinemia” and considered an idiopathic vasculitis. -

Identification of Microorganisms Using Nucleic Acid Probes

Identification of Microorganisms Using Page 1 of 45 Nucleic Acid Probes Medical Policy An Independent Licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association Title: Identification of Microorganisms Using Nucleic Acid Probes See Also: Influenza Virus Diagnostic Testing and Treatment in the Outpatient Setting Professional Institutional Original Effective Date: July 8, 2008 Original Effective Date: July 16, 2009 Revision Date(s): June 16, 2009; Revision Date(s): March 1, 2012; March 1, 2012; June 5, 2012; June 5, 2012; November 19, 2012; November 19, 2012; January 15, 2013; January 15, 2013; November 12, 2013 November 12, 2013 Current Effective Date: November 12, 2013 Current Effective Date: November 12, 2013 State and Federal mandates and health plan member contract language, including specific provisions/exclusions, take precedence over Medical Policy and must be considered first in determining eligibility for coverage. To verify a member's benefits, contact Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas Customer Service. The BCBSKS Medical Policies contained herein are for informational purposes and apply only to members who have health insurance through BCBSKS or who are covered by a self-insured group plan administered by BCBSKS. Medical Policy for FEP members is subject to FEP medical policy which may differ from BCBSKS Medical Policy. The medical policies do not constitute medical advice or medical care. Treating health care providers are independent contractors and are neither employees nor agents of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas and are solely responsible for diagnosis, treatment and medical advice. If your patient is covered under a different Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan, please refer to the Medical Policies of that plan. -

A Review of Primary Vasculitis Mimickers Based on the Chapel Hill Consensus Classification

Hindawi International Journal of Rheumatology Volume 2020, Article ID 8392542, 11 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8392542 Review Article A Review of Primary Vasculitis Mimickers Based on the Chapel Hill Consensus Classification Farah Zarka ,1 Charles Veillette ,1 and Jean-Paul Makhzoum 2 1Hôpital du Sacré-Cœur de Montreal, University of Montreal, Canada 2Vasculitis Clinic, Department of Internal Medicine, Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montreal, University of Montreal, Canada Correspondence should be addressed to Jean-Paul Makhzoum; [email protected] Received 10 July 2019; Accepted 7 January 2020; Published 18 February 2020 Academic Editor: Charles J. Malemud Copyright © 2020 Farah Zarka et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Primary systemic vasculitides are rare diseases that may manifest similarly to more commonly encountered conditions. Depending on the size of the vessel affected (large vessel, medium vessel, or small vessel), different vasculitis mimics must be considered. Establishing the right diagnosis of a vasculitis mimic will prevent unnecessary immunosuppressive therapy. 1. Introduction 2. Large-Vessel Vasculitis Mimics Vasculitides are rare heterogenous diseases that affect vessel Large-vessel vasculitis (LVV) is an inflammatory vascu- walls as the main site of inflammation. Organs affected vary lopathy affecting large arteries; giant cell arteritis (GCA) depending on the type and size of blood vessels involved and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) are the two main docu- [1]. Autoimmune vasculitis can be primary (idiopathic) or mented variants, each with their own characteristic fea- secondary to an underlying disease. -

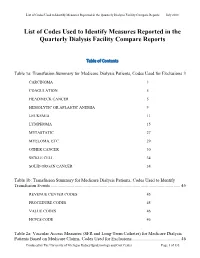

List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the QDFC

List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports July 2018 List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports Table of Contents Table 1a: Transfusion Summary for Medicare Dialysis Patients, Codes Used for Exclusions 3 CARCINOMA 3 COAGULATION 5 HEAD/NECK CANCER 5 HEMOLYTIC OR APLASTIC ANEMIA 9 LEUKEMIA 11 LYMPHOMA 15 METASTATIC 27 MYELOMA, ETC. 29 OTHER CANCER 30 SICKLE CELL 34 SOLID ORGAN CANCER 34 Table 1b: Transfusion Summary for Medicare Dialysis Patients, Codes Used to Identify Transfusion Events .................................................................................................................. 45 REVENUE CENTER CODES 45 PROCEDURE CODES 45 VALUE CODES 46 HCPCS CODE 46 Table 2a: Vascular Access Measures (SFR and Long-Term Catheter) for Medicare Dialysis Patients Based on Medicare Claims, Codes Used for Exclusions ........................................... 46 Produced by The University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center Page 1 of 135 List of Codes Used to Identify Measures Reported in the Quarterly Dialysis Facility Compare Reports July 2018 COMA 46 END STAGE LIVER DISEASE 48 METASTATIC CANCER 48 Table 2b: Standardized Fistulae Rate (SFR) for Medicare Dialysis Patients Based on Medicare Claims, Codes Used for Prevalent Comorbidities Adjusted in Model .................................... 50 ANEMIA 50 CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE 52 CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE 55 CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE 56 CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE 68 DIABETES 69 DRUG DEPENDENCE 79 INFECTIONS (NON-VASCULAR ACCESS-RELATED): 93 PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE (INCLUDES ARTERIAL, VENOUS AND NONSPECIFIC DISEASES) 124 Table 3: Dialysis Adequacy ................................................................................................... -

Lecture 1 ― INTRODUCTION INTO MICROBIOLOGY

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ БЕЛАРУСЬ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ «ГОМЕЛЬСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ» Кафедра микробиологии, вирусологии и иммунологии А. И. КОЗЛОВА, Д. В. ТАПАЛЬСКИЙ МИКРОБИОЛОГИЯ, ВИРУСОЛОГИЯ И ИММУНОЛОГИЯ Учебно-методическое пособие для студентов 2 и 3 курсов факультета по подготовке специалистов для зарубежных стран медицинских вузов MICROBIOLOGY, VIROLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY Teaching workbook for 2 and 3 year students of the Faculty on preparation of experts for foreign countries of medical higher educational institutions Гомель ГомГМУ 2015 УДК 579+578+612.017.1(072)=111 ББК 28.4+28.3+28.073(2Англ)я73 К 59 Рецензенты: доктор медицинских наук, профессор, заведующий кафедрой клинической микробиологии Витебского государственного ордена Дружбы народов медицинского университета И. И. Генералов; кандидат медицинских наук, доцент, доцент кафедры эпидемиологии и микробиологии Белорусской медицинской академии последипломного образования О. В. Тонко Козлова, А. И. К 59 Микробиология, вирусология и иммунология: учеб.-метод. пособие для студентов 2 и 3 курсов факультета по подготовке специалистов для зарубежных стран медицинских вузов = Microbiology, virology and immunology: teaching workbook for 2 and 3 year students of the Faculty on preparation of experts for foreign countries of medical higher educa- tional institutions / А. И. Козлова, Д. В. Тапальский. — Гомель: Гом- ГМУ, 2015. — 240 с. ISBN 978-985-506-698-0 В учебно-методическом пособии представлены тезисы лекций по микробиоло- гии, вирусологии и иммунологии, рассмотрены вопросы морфологии, физиологии и генетики микроорганизмов, приведены сведения об общих механизмах функциони- рования системы иммунитета и современных иммунологических методах диагности- ки инфекционных и неинфекционных заболеваний. Приведены сведения об этиоло- гии, патогенезе, микробиологической диагностике и профилактике основных бакте- риальных и вирусных инфекционных заболеваний человека. Может быть использовано для закрепления материала, изученного в курсе микро- биологии, вирусологии, иммунологии. -

Tabes Dorsalis and Perforated Duodenal Ulcer J

i6o Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.37.425.160 on 1 March 1961. Downloaded from POSTGRAD. MED. J. (1961), 37, i60 TABES DORSALIS AND PERFORATED DUODENAL ULCER J. P. LAWSON, M.B., Ch.B. Late Senior House Officer in Medicine, Crumpsall Hospital, Manchester Senior House Oficer in Radiology, David Lewis Northern Hospital, Liverpool 3 IT is well recorded that tabes dorsalis can mask between the shoulder blades whilst standing in a bus serious visceral disease. Wilson mentions queue. This was shortly followed by a bout of vomiting (1954) and sweating. There was no dyspncea, pain in the chest that tabes can disrupt nervous pathways so as to or abdominal pain. The patient was able to make his produce a visceral analgesia capable of masking own way home on foot. serious abdominal disease. At home he took a Sedlitz powder, which was followed by three further attacks of vomiting and four Connor (I91o) published a case of a brakeman, loose bowel actions. There was no blood in either aged 42, who died in hospital following an acute vomitus or faeces. The pain spread to both shoulder febrile attack and vomiting. There had been no tips, where it persisted and was the cause of his attend- abdominal tenderness or to ance at the casualty department. pain, rigidity explain Four years previously he had developed a similar the condition but autopsy revealed a perforated attack of sweating and stated that he had also vomited appendix abscess and peritonitis. blood. At this time he was apparently found to be from and was trans- Hanser (I9I9) recorded the case of a tabetic suffering pulmonary tuberculosis, by copyright. -

Diagnosis One To

Diagnosis One-to-One I9cm I9 Long Desc I10cm I10 Long Desc 0010 Cholera due to vibrio cholerae A000 Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar cholerae 0011 Cholera due to vibrio cholerae el tor A001 Cholera due to Vibrio cholerae 01, biovar eltor 0019 Cholera, unspecified A009 Cholera, unspecified 0021 Paratyphoid fever A A011 Paratyphoid fever A 0022 Paratyphoid fever B A012 Paratyphoid fever B 0023 Paratyphoid fever C A013 Paratyphoid fever C 0029 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified A014 Paratyphoid fever, unspecified 0030 Salmonella gastroenteritis A020 Salmonella enteritis 0031 Salmonella septicemia A021 Salmonella sepsis 00320 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified A0220 Localized salmonella infection, unspecified 00321 Salmonella meningitis A0221 Salmonella meningitis 00322 Salmonella pneumonia A0222 Salmonella pneumonia 00323 Salmonella arthritis A0223 Salmonella arthritis 00324 Salmonella osteomyelitis A0224 Salmonella osteomyelitis 0038 Other specified salmonella infections A028 Other specified salmonella infections 0039 Salmonella infection, unspecified A029 Salmonella infection, unspecified 0040 Shigella dysenteriae A030 Shigellosis due to Shigella dysenteriae 0041 Shigella flexneri A031 Shigellosis due to Shigella flexneri 0042 Shigella boydii A032 Shigellosis due to Shigella boydii 0043 Shigella sonnei A033 Shigellosis due to Shigella sonnei 0048 Other specified shigella infections A038 Other shigellosis 0049 Shigellosis, unspecified A039 Shigellosis, unspecified 0050 Staphylococcal food poisoning A050 Foodborne staphylococcal -

BQI Icare HIV/AIDS

RESOURCE AND PATIENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM iCare Population Management GUI (BQI) HIV/AIDS Management User Manual Version 2.6 July 2017 Office of Information Technology (OIT) Division of Information Technology iCare Population Management GUI (BQI) Version 2.6 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Key Functional Features .......................................................................... 1 1.2 Sensitive Patient Data ............................................................................. 2 2.0 Patient Management ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 Data Specifically Related to HIV/AIDS ..................................................... 3 2.2 Search for and View a Patient Record ..................................................... 6 2.2.1 Using a Panel ........................................................................................ 6 2.2.2 Using Quick Search ............................................................................... 7 2.3 Displaying Care Management as Default Tab ......................................... 8 2.4 Add/Edit Care Management Data ............................................................ 8 2.4.1 Entering Data on the General Area ....................................................... 9 2.4.2 Entering Data on the Partner Notification Area .................................... 11 2.4.3 Entering Data on the Antiretroviral -

United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,464,124 B2 Bancel Et Al

USOO9464124B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,464,124 B2 Bancel et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 11, 2016 (54) ENGINEERED NUCLEIC ACIDS AND 4,500,707 A 2f1985 Caruthers et al. METHODS OF USE THEREOF 4,579,849 A 4, 1986 MacCoSS et al. 4,588,585 A 5/1986 Mark et al. 4,668,777 A 5, 1987 Caruthers et al. (71) Applicant: Moderna Therapeutics, Inc., 4,737.462 A 4, 1988 Mark et al. Cambridge, MA (US) 4,816,567 A 3/1989 Cabilly et al. 4,879, 111 A 11/1989 Chong (72) Inventors: Stephane Bancel, Cambridge, MA 4,957,735 A 9/1990 Huang (US); Jason P. Schrum, Philadelphia, 4.959,314 A 9, 1990 Mark et al. 4,973,679 A 11/1990 Caruthers et al. PA (US); Alexander Aristarkhov, 5.012.818 A 5/1991 Joishy Chestnut Hill, MA (US) 5,017,691 A 5/1991 Lee et al. 5,021,335 A 6, 1991 Tecott et al. (73) Assignee: Moderna Therapeutics, Inc., 5,036,006 A 7, 1991 Sanford et al. Cambridge, MA (US) 9. A 228 at al. J. J. W. OS a 5,130,238 A 7, 1992 Malek et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,132,418 A 7, 1992 °N, al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,153,319 A 10, 1992 Caruthers et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,168,038 A 12/1992 Tecott et al. 5,169,766 A 12/1992 Schuster et al. -

Tomonidan Ithutuotte

TOMONIDANUS010022425B2 ITHUTUOTTE (12 ) United States Patent (10 ) Patent No. : US 10 ,022 , 425 B2 Bancel et al. ( 45) Date of Patent : Jul. 17 , 2018 ( 54 ) ENGINEERED NUCLEIC ACIDS AND 4 , 399 ,216 A 8 / 1983 Axel et al. METHODS OF USE THEREOF 4 ,401 , 796 A 8 / 1983 Itakura 4 ,411 ,657 A 10 / 1983 Galindo 4 ,415 , 732 A 11/ 1983 Caruthers et al . @(71 ) Applicant : Moderna TX , Inc ., Cambridge , MA 4 ,458 , 066 A 7 / 1984 Caruthers et al. (US ) 4 , 474 , 569 A 10 / 1984 Newkirk 4 ,500 ,707 A 2 / 1985 Caruthers et al . @(72 ) Inventors : Stephane Bancel, Cambridge , MA 4 , 579 , 849 A 4 / 1986 MacCoss et al. 4 ,588 , 585 A 5 / 1986 Mark et al. (US ) ; Jason P . Schrum , Philadelphia , 4 ,668 , 777 A 5 / 1987 Caruthers et al . PA (US ) ; Alexander Aristarkhov , 4 , 737 ,462 A 4 / 1988 Mark et al . Chestnut Hill, MA (US ) 4 ,816 , 567 A 3 / 1989 Cabilly et al . 4 ,879 , 111 A 11 /1989 Chong ( 73 ) Assignee : ModernaTX , Inc. , Cambridge, MA 4 , 957 , 735 A 9 / 1990 Huang 4 , 959 , 314 A 9 / 1990 Mark et al. (US ) 4 ,973 ,679 A 11/ 1990 Caruthers et al. 5 ,012 ,818 A 5 / 1991 Joishy @( * ) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5 ,017 ,691 A 5 / 1991 Lee et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5 ,021 , 335 A 6 / 1991 Tecott et al. U . S . C . 154 (b ) by 0 days . 5 , 036 , 006 A 7 / 1991 Sanford et al . 5 , 047 ,524 A 9 / 1991 Andrus et al . -

Report for the Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Standardized Fistula Rate

ESRD Quality Measure Development, Maintenance, and Support Contract Number HHSM-500-2013-13017I Report for the Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Standardized Fistula Rate (SFR) NQF #2977 Submitted to CMS by the University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center June 21, 2017 Produced by UM-KECC Submitted: 6.21.2017 1 ESRD Quality Measure Development, Maintenance, and Support Contract Number HHSM-500-2013-13017I Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Overview ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Data Sources ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Outcome Definition .................................................................................................................................. 4 Denominator Definition ............................................................................................................................ 5 Risk Adjustment ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Choosing Adjustment Factors -

Are Those of Longcope', Allbutt23, and Reid45. 662 Negroes Who Had Syphilis

656 Ti, CANADIN MEDICAL ASsOcIATIoN JOURNAL [Nov. 1930 SYPHILIS OF THE AORTA AND HEART* A CLINICAL STUDY BY SAMUEL S. RIVEN, M.D., Ann Arbor, Mich., and J. FEIGENBAUM, M.D., Montreal THIS article presents a summary of the clinical can be demonstrated microscopically in findings in a series of 74 patients with practically 100 per cent of the cases syphilitic cardiovascular disease observed at Very different is the case in the syphilitic female. the University Hospital, Arn Arbor, between In a large proportion of such, no characteristic July, 1925 and July, 1927. Seven of these gross or microscopic syphilitic lesions can be patients were subjected to autopsy. In the found in either aorta or heart." remaining instances the diagnosis was made on Racial incidence.-Sixty-four of the patients the history, and the clinical and laboratory here reported belonged-to the white race and findings. No doubtful cases were included. 10 to the coloured r4k. The proportion in The clinical diagnoses are summarized in Table I. Scott's series between white and coloured in- There is an extensive literature dealing with dividuals was 34 to 41. Paullin found evidence this subject. Among the more important studies of cardiovascular syphilis in 39 per cent of are those of Longcope', Allbutt23, and Reid45. 662 negroes who had syphilis. This percentage We have compared our data with the findings is apparently not any greater than occurs in of these and various other authors. the white population with syphilis. No definite conclusion can be drawn regarding the pre- TABLE I. disposition of negroes to syphilis of the circulatory Clinical Diagnosis No.