10 Differential Diagnosis of Atopic Eczema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Diagnostic Approach to Pruritus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Air Force Research U.S. Department of Defense 2011 A Diagnostic Approach to Pruritus Brian V. Reamy Christopher W. Bunt Stacy Fletcher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usafresearch This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. Air Force Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Diagnostic Approach to Pruritus BRIAN V. REAMY, MD, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland CHRISTOPHER W. BUNT, MAJ, USAF, MC, and STACY FLETCHER, CAPT, USAF, MC Ehrling Bergquist Family Medicine Residency Program, Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, and the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska Pruritus can be a symptom of a distinct dermatologic condition or of an occult underlying systemic disease. Of the patients referred to a dermatologist for generalized pruritus with no apparent primary cutaneous cause, 14 to 24 percent have a systemic etiology. In the absence of a primary skin lesion, the review of systems should include evaluation for thyroid disorders, lymphoma, kidney and liver diseases, and diabetes mellitus. Findings suggestive of less seri- ous etiologies include younger age, localized symptoms, acute onset, involvement limited to exposed areas, and a clear association with a sick contact or recent travel. Chronic or general- ized pruritus, older age, and abnormal physical findings should increase concern for underly- ing systemic conditions. -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Clinical and Histopathological Study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka

ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Clinical and Histopathological study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka. Khaled A1, Banu SG 2, Kamal M 3, Manzoor J 4, Nasir TA 5 Introduction studies from other countries. Skin diseases manifested by lichenoid eruption, With this background, this present study was is common in our country. Patients usually undertaken to know the clinical and attend the skin disease clinic in advanced stage histopathological pattern of lichenoid eruption, of disease because of improper treatment due to age and sex distribution of the diseases and to difficulties in differentiation of myriads of well assess the clinical diagnostic accuracy by established diseases which present as lichenoid histopathology. eruption. When we call a clinical eruption lichenoid, we Materials and Method usually mean it resembles lichen planus1, the A total of 134 cases were included in this study prototype of this group of disease. The term and these cases were collected from lichenoid used clinically to describe a flat Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University topped, shiny papular eruption resembling 2 (Jan 2003 to Feb 2005) and Apollo Hospitals lichen planus. Histopathologically these Dhaka (Oct 2006 to May 2008), both of these are diseases show lichenoid tissue reaction. The large tertiary care hospitals in Dhaka. Biopsy lichenoid tissue reaction is characterized by specimen from patients of all age group having epidermal basal cell damage that is intimately lichenoid eruption was included in this study. associated with massive infiltration of T cells in 3 Detailed clinical history including age, sex, upper dermis. distribution of lesions, presence of itching, The spectrum of clinical diseases related to exacerbating factors, drug history, family history lichenoid tissue reaction is wider and usually and any systemic manifestation were noted. -

Common Dermatoses in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Mircea Tampa Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tampa [email protected]

Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 7 2015 Common Dermatoses in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Mircea Tampa Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, [email protected] Maria Isabela Sarbu Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, [email protected] Clara Matei Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Vasile Benea Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases Simona Roxana Georgescu Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Tampa, Mircea; Sarbu, Maria Isabela; Matei, Clara; Benea, Vasile; and Georgescu, Simona Roxana (2015) "Common Dermatoses in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorders," Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol2/iss2/7 This Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. JMMS 2015, 2(2): 150- 158. Review Common dermatoses in patients with obsessive compulsive disorders Mircea Tampa1, Maria Isabela Sarbu2, Clara Matei1, Vasile Benea2, Simona Roxana Georgescu1 1 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Dermatology and Venereology 2 Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Dermatology and Venereology Corresponding author: Maria Isabela Sarbu, e-mail: [email protected] Running title: Dermatoses in obsessive compulsive disorders Keywords: Factitious disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, acne excoriee www.jmms.ro 2015, Vol. -

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

LICHEN SIMPLEX CHRONICUS http://www.aocd.org Lichen simplex chronicus is a localized form of lichenified (thickened, inflamed) atopic dermatitis or eczema that occurs in well defined plaques. It is the result of ongoing, chronic rubbing and scratching of the skin in localized areas. It is generally seen in patients greater than 20 years of age and is more frequent in women. Emotional stress can play a part in the course of this skin disease. There is mainly one symptom: itching. The rubbing and scratching that occurs in response to the itch can become automatic and even unconscious making it very difficult to treat. It can be magnified by seeming innocuous stimuli such as putting on clothes, or clothes rubbing the skin which makes the skin warmer resulting in increased itch sensation. The lesions themselves are generally very well defined areas of thickened, erythematous, raised area of skin. Frequently they are linear, oval or round in shape. Sites of predilection include the back of the neck, ankles, lower legs, upper thighs, forearms and the genital areas. They can be single lesions or multiple. This can be a very difficult condition to treat much less resolve. It is of utmost importance that the scratching and rubbing of the skin must stop. Treatment is usually initiated with topical corticosteroids for larger areas and intralesional steroids might also be considered for small lesion(s). If the patient simply cannot keep from rubbing the area an occlusive dressing might be considered to keep the skin protected from probing fingers. Since this is not a histamine driven itch phenomena oral antihistamines are generally of little use in these cases. -

Triamcinolone Acetonide Injectable Suspension, USP)

KENALOG®-10 INJECTION (triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension, USP) NOT FOR USE IN NEONATES CONTAINS BENZYL ALCOHOL For Intra-articular or Intralesional Use Only NOT FOR INTRAVENOUS, INTRAMUSCULAR, INTRAOCULAR, EPIDURAL, OR INTRATHECAL USE DESCRIPTION Kenalog®-10 Injection (triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension, USP) is triamcinolone acetonide, a synthetic glucocorticoid corticosteroid with marked anti-inflammatory action, in a sterile aqueous suspension suitable for intralesional and intra-articular injection. THIS FORMULATION IS SUITABLE FOR INTRA-ARTICULAR AND INTRALESIONAL USE ONLY. Each mL of the sterile aqueous suspension provides 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide, with 0.66% sodium chloride for isotonicity, 0.99% (w/v) benzyl alcohol as a preservative, 0.63% carboxymethylcellulose sodium, and 0.04% polysorbate 80. Sodium hydroxide or hydrochloric acid may have been added to adjust pH between 5.0 and 7.5. At the time of manufacture, the air in the container is replaced by nitrogen. The chemical name for triamcinolone acetonide is 9-Fluoro-11β,16α,17,21-tetrahydroxypregna- 1,4-diene-3,20-dione cyclic 16,17-acetal with acetone. Its structural formula is: 1 Reference ID: 4241593 MW 434.50 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Glucocorticoids, naturally occurring and synthetic, are adrenocortical steroids that are readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Naturally occurring glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone and cortisone), which also have salt- retaining properties, are used as replacement therapy in adrenocortical deficiency states. -

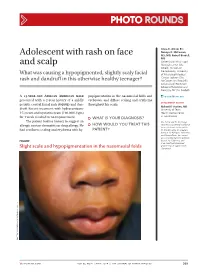

Adolescent with Rash on Face and Scalp

Photo RoUNDS Anna K. Allred, BS; Nancye K. McCowan, Adolescent with rash on face MS, MD; Robert Brodell, MD University of Mississippi and scalp Medical Center (Ms. Allred); Division of Dermatology, University What was causing a hypopigmented, slightly scaly facial of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson (Drs. rash and dandruff in this otherwise healthy teenager? McCowan and Brodell); University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, NY (Dr. Brodell) A 13-year-old African American male popigmentation in the nasomesial folds and [email protected] presented with a 2-year history of a mildly eyebrows, and diffuse scaling and erythema DEpartment EDItOR pruritic central facial rash (FIGURE) and dan- throughout his scalp. Richard p. Usatine, MD druff. Recent treatment with hydrocortisone University of Texas 1% cream and nystatin cream (100,000 U/gm) Health Science Center at San Antonio for 1 week resulted in no improvement. ● What is youR diAgnosis? The patient had no history to suggest an Ms. Allred and Dr. McCowan allergic contact dermatitis or drug allergy. He ● HoW Would you TReAT THIS reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article. had confluent scaling and erythema with hy- pATIENT? Dr. Brodell serves on speaker’s bureaus for Allergan, Galderma, and PharmaDerm, has served as a consultant and on advisory Figure boards for Galderma, and is an investigator/received grant/research support from Slight scale and hypopigmentation in the nasomesial folds Genentech. PHO T o COU RT ESY OF : R o B e RT BR ODELL , MD jfponline.com Vol 63, no 4 | ApRIL 2014 | The jouRnAl of Family PracTice 209 PHOTO RoUNDS Diagnosis: the Malassezia yeast and topical steroids are Seborrheic dermatitis used to suppress inflammation. -

Chronic Pruritic Vulva Lesion

Photo RoUNDS Stephen Colden Cahill, DO Chronic pruritic vulva lesion College of Osteopathic Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing; The patient was not sexually active and denied any and Lakeshore Health vaginal discharge. So what was causing the intense Partners, Holland, Mich itching on her labia? [email protected] Department eDItOr richard p. Usatine, mD University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio During a routine exam, a 45-year-old Cau- both of her labia majora (FIGURE). Throughout casian woman complained of intense itching the lesion, there were scattered areas of exco- The author reported no potential conflict of interest on her labia. She said that the itching had been riation. Her labia minor were spared. relevant to this article. an issue for more than 9 months and that she A speculum and bimanual exam were found herself scratching several times a day. normal. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was She denied any vaginal discharge and said she present. hadn’t been sexually active in years. She had tried over-the-counter antifungals and topical ● WhaT is your diagnosis? Benadryl, but they provided only limited relief. The patient had red thickened plaques ● HoW Would you TREAT THIS with accentuated skin lines (furrows) covering PATIENT? Figure Red thickened plaques on labia majora p ho T o cour T esy of: St ephen c olden c ahill, DO jfponline.com Vol 62, no 2 | february 2013 | The journal of family pracTice 97 PHOTO RoUNDS Diagnosis: taneous lesion of unknown etiology. It can Lichen simplex chronicus be found throughout the body, including the This patient was given a diagnosis of lichen mucous membranes. -

Views in Allergy and Immunology

CLINICAL REVIEWS IN ALLERGY AND IMMUNOLOGY Dermatology for the Allergist Dennis Kim, MD, and Richard Lockey, MD specific laboratory tests and pathognomonic skin findings do Abstract: Allergists/immunologists see patients with a variety of not exist (Table 1). skin disorders. Some, such as atopic and allergic contact dermatitis, There are 3 forms of AD: acute, subacute, and chronic. are caused by abnormal immunologic reactions, whereas others, Acute AD is characterized by intensely pruritic, erythematous such as seborrheic dermatitis or rosacea, lack an immunologic basis. papules associated with excoriations, vesiculations, and se- This review summarizes a select group of dermatologic problems rous exudates. Subacute AD is associated with erythematous, commonly encountered by an allergist/immunologist. excoriated, scaling papules. Chronic AD is associated with Key Words: dermatology, dermatitis, allergy, allergic, allergist, thickened lichenified skin and fibrotic papules. There is skin, disease considerable overlap of these 3 forms, especially with chronic (WAO Journal 2010; 3:202–215) AD, which can manifest in all 3 ways in the same patient. The relationship between AD and causative allergens is difficult to establish. However, clinical studies suggest that extrinsic factors can impact the course of disease. Therefore, in some cases, it is helpful to perform skin testing on foods INTRODUCTION that are commonly associated with food allergy (wheat, milk, llergists/immunologists see patients with a variety of skin soy, egg, peanut, tree nuts, molluscan, and crustaceous shell- Adisorders. Some, such as atopic and allergic contact fish) and aeroallergens to rule out allergic triggers that can dermatitis, are caused by abnormal immunologic reactions, sometimes exacerbate this disease. -

Lichen Simplex Chronicus: Easy Psychological Interventions That Every Dermatologist Should Know

SMGr up Review Article SM Dermatology Lichen Simplex Chronicus: Easy Journal Psychological Interventions that Every Dermatologist Should Know Julio Torales1*, Iván Barrios2, Liz Lezcano3 and Beatriz Di Martino4 1Professor and Head of the Psychodermatology Unit, Clinicas Hospital, National University of Asunción, Paraguay, USA 2Student fellow, Neuroscience Department, Clinicas Hospital, National University of Asunción, Paraguay, USA 3Professor of Dermatology, Clinicas Hospital, National University of Asunción, Paraguay, USA 4Professor and Head of the Dermato-pathology Unit, Clinicas Hospital, National University of Asunción, Paraguay, USA Article Information Abstract Received date: Jul 02, 2016 Lichen Simplex Chronicus (LSC) is a chronic skin disease characterized by lichenified plaques, which Accepted date: Nov 04, 2016 occur as result of constant scratching or rubbing of skin. Pruritus is the predominant symptom that leads to the development of LSC. Frequent pruritus triggers include mechanical irritation, environmental factors, such as heat Published date: Nov 10, 2016 and sweating, and psychological factors, such as stress and anxiety. *Corresponding author From a psychodermatology point of view, the interruption of the never-ending itch-scratch cycle, which characterizes LSC, is of supreme importance for patient’s recovery. Furthermore, emotional tensions, as seen Julio Torales, Professor and Head in patients with anxiety, depression, or obsessive-compulsive disorder, may play a key role in inducing a pruritic of the Psychodermatology Unit, sensation, leading to scratching that can become self-perpetuating. National University of Asunción, Referral to a psychiatrist or a psychotherapist might be required in many cases. However, this referral San Lorenzo - Paraguay, USA, could be difficult in daily practice, given the patient’s unwillingness to seek mental health counseling. -

Skin Damage from Chronic Irritation Or Scratching

Skin Damage from Chronic Irritation or Scratching Chronic irritation and scratching can cause skin damage to the vulva. Confusingly, this may be called many different things like Eczema, Lichen Simplex Chronicus (LSC), Chronic Dermatitis or Squamous Cell Hyperplasia. Some of these diagnoses require that a biopsy of the vulva has been performed; others are based just on clinical opinion after history and physical examination. Many things can trigger irritation of the vulva. For instance, scratching alone can lead to changes on the vulva that can be seen on physical exam or self-inspection. Often the original event that precipitated irritation and itching is unknown. Sometimes it is a vaginal infection, sometimes it is a contact irritant and sometimes it is a nervous itch. Regardless, the skin becomes irritated and inflamed, therefore beginning the “Scratch-Itch” cycle. Once this cycle is perpetuated, it is difficult for the vulvar skin to heal and the changes persist. When a biopsy is performed, it can greatly assist your practitioner in finding a diagnosis that can lead to successful treatment. Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) and Squmous Cell Hyperplasia are 2 diagnoses that can be rendered after a skin biopsy. These are essentially similar entities and are defined as abnormal thickening of the skin of the vulva. Two thirds of patients who develop this condition are premenopausal. Moisture, chronic scratching, scrubbing, allergens, and medications may cause variations in the appearance of the lesions. The size of the lesions ranges from small to large, red to white, excoriated to eroded, and most frequently involve certain areas of the vulva like the hood of the clitoris, the labia majora, the interlabial sulcus (space between major and minor lips) outer aspect of the labia minora, and the perineal body (space between anus and vaginal opening). -

Dermatology in Geriatrics a Gandhi, M Gandhi, S Kalra

The Internet Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology ISPUB.COM Volume 5 Number 2 Dermatology in Geriatrics A Gandhi, M Gandhi, S Kalra Citation A Gandhi, M Gandhi, S Kalra. Dermatology in Geriatrics. The Internet Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology. 2009 Volume 5 Number 2. Abstract Over the past few years the world's population has continued on its remarkable transition from a state of high birth and death rates to one characterized by low birth and death rates. Consequently, primary care physicians and dermatologists will see more elderly patients presenting age related dermatological conditions.As people age, their chances of developing skin-related disorders increase due to multiple underlying medical conditions i.e. diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis and decreased immunity. Common skin disorders found in the elderly individual are xerosis, pruritus, eczematous dermatitis, purpura, chronic venous insufficiency, psychocutaneous disorders etc. Caregivers and medical personnel can help decrease or prevent the development of many skin disorders in the elderly by addressing several factors i.e patient’s nutritional status, medical history, current medications, allergies, physical limitations, mental state, and personal hygiene and for specific underlying etiologies; several pharmacological treatment choices are suggested. INTRODUCTION and assisted living facilities3 .Caregivers and medical The famous old saying OLD IS GOLD doesn’t apply to personnel can help decrease or prevent the development of human skin as elderly people are recognized by their many skin disorders in the elderly by addressing several wrinkled and dull skin. The population is getting older, with factors i.e patient’s nutritional state, medical history, current a greater percentage of the population in the over-65 age medications, allergies, physical limitations, mental state, and group. -

86A1bedb377096cf412d7e5f593

Contents Gray..................................................................................... Section: Introduction and Diagnosis 1 Introduction to Skin Biology ̈ 1 2 Dermatologic Diagnosis ̈ 16 3 Other Diagnostic Methods ̈ 39 .....................................................................................Blue Section: Dermatologic Diseases 4 Viral Diseases ̈ 53 5 Bacterial Diseases ̈ 73 6 Fungal Diseases ̈ 106 7 Other Infectious Diseases ̈ 122 8 Sexually Transmitted Diseases ̈ 134 9 HIV Infection and AIDS ̈ 155 10 Allergic Diseases ̈ 166 11 Drug Reactions ̈ 179 12 Dermatitis ̈ 190 13 Collagen–Vascular Disorders ̈ 203 14 Autoimmune Bullous Diseases ̈ 229 15 Purpura and Vasculitis ̈ 245 16 Papulosquamous Disorders ̈ 262 17 Granulomatous and Necrobiotic Disorders ̈ 290 18 Dermatoses Caused by Physical and Chemical Agents ̈ 295 19 Metabolic Diseases ̈ 310 20 Pruritus and Prurigo ̈ 328 21 Genodermatoses ̈ 332 22 Disorders of Pigmentation ̈ 371 23 Melanocytic Tumors ̈ 384 24 Cysts and Epidermal Tumors ̈ 407 25 Adnexal Tumors ̈ 424 26 Soft Tissue Tumors ̈ 438 27 Other Cutaneous Tumors ̈ 465 28 Cutaneous Lymphomas and Leukemia ̈ 471 29 Paraneoplastic Disorders ̈ 485 30 Diseases of the Lips and Oral Mucosa ̈ 489 31 Diseases of the Hairs and Scalp ̈ 495 32 Diseases of the Nails ̈ 518 33 Disorders of Sweat Glands ̈ 528 34 Diseases of Sebaceous Glands ̈ 530 35 Diseases of Subcutaneous Fat ̈ 538 36 Anogenital Diseases ̈ 543 37 Phlebology ̈ 552 38 Occupational Dermatoses ̈ 565 39 Skin Diseases in Different Age Groups ̈ 569 40 Psychodermatology