A Diagnostic Approach to Pruritus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Clinical and Histopathological Study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka

ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Clinical and Histopathological study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka. Khaled A1, Banu SG 2, Kamal M 3, Manzoor J 4, Nasir TA 5 Introduction studies from other countries. Skin diseases manifested by lichenoid eruption, With this background, this present study was is common in our country. Patients usually undertaken to know the clinical and attend the skin disease clinic in advanced stage histopathological pattern of lichenoid eruption, of disease because of improper treatment due to age and sex distribution of the diseases and to difficulties in differentiation of myriads of well assess the clinical diagnostic accuracy by established diseases which present as lichenoid histopathology. eruption. When we call a clinical eruption lichenoid, we Materials and Method usually mean it resembles lichen planus1, the A total of 134 cases were included in this study prototype of this group of disease. The term and these cases were collected from lichenoid used clinically to describe a flat Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University topped, shiny papular eruption resembling 2 (Jan 2003 to Feb 2005) and Apollo Hospitals lichen planus. Histopathologically these Dhaka (Oct 2006 to May 2008), both of these are diseases show lichenoid tissue reaction. The large tertiary care hospitals in Dhaka. Biopsy lichenoid tissue reaction is characterized by specimen from patients of all age group having epidermal basal cell damage that is intimately lichenoid eruption was included in this study. associated with massive infiltration of T cells in 3 Detailed clinical history including age, sex, upper dermis. distribution of lesions, presence of itching, The spectrum of clinical diseases related to exacerbating factors, drug history, family history lichenoid tissue reaction is wider and usually and any systemic manifestation were noted. -

Common Dermatoses in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Mircea Tampa Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tampa [email protected]

Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 7 2015 Common Dermatoses in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorders Mircea Tampa Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, [email protected] Maria Isabela Sarbu Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, [email protected] Clara Matei Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Vasile Benea Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases Simona Roxana Georgescu Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Tampa, Mircea; Sarbu, Maria Isabela; Matei, Clara; Benea, Vasile; and Georgescu, Simona Roxana (2015) "Common Dermatoses in Patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorders," Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol2/iss2/7 This Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. JMMS 2015, 2(2): 150- 158. Review Common dermatoses in patients with obsessive compulsive disorders Mircea Tampa1, Maria Isabela Sarbu2, Clara Matei1, Vasile Benea2, Simona Roxana Georgescu1 1 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Dermatology and Venereology 2 Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department of Dermatology and Venereology Corresponding author: Maria Isabela Sarbu, e-mail: [email protected] Running title: Dermatoses in obsessive compulsive disorders Keywords: Factitious disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, acne excoriee www.jmms.ro 2015, Vol. -

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

LICHEN SIMPLEX CHRONICUS http://www.aocd.org Lichen simplex chronicus is a localized form of lichenified (thickened, inflamed) atopic dermatitis or eczema that occurs in well defined plaques. It is the result of ongoing, chronic rubbing and scratching of the skin in localized areas. It is generally seen in patients greater than 20 years of age and is more frequent in women. Emotional stress can play a part in the course of this skin disease. There is mainly one symptom: itching. The rubbing and scratching that occurs in response to the itch can become automatic and even unconscious making it very difficult to treat. It can be magnified by seeming innocuous stimuli such as putting on clothes, or clothes rubbing the skin which makes the skin warmer resulting in increased itch sensation. The lesions themselves are generally very well defined areas of thickened, erythematous, raised area of skin. Frequently they are linear, oval or round in shape. Sites of predilection include the back of the neck, ankles, lower legs, upper thighs, forearms and the genital areas. They can be single lesions or multiple. This can be a very difficult condition to treat much less resolve. It is of utmost importance that the scratching and rubbing of the skin must stop. Treatment is usually initiated with topical corticosteroids for larger areas and intralesional steroids might also be considered for small lesion(s). If the patient simply cannot keep from rubbing the area an occlusive dressing might be considered to keep the skin protected from probing fingers. Since this is not a histamine driven itch phenomena oral antihistamines are generally of little use in these cases. -

Photodermatoses Update Knowledge and Treatment of Photodermatoses Discuss Vitamin D Levels in Photodermatoses

Ashley Feneran, DO Jenifer Lloyd, DO University Hospitals Regional Hospitals AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC COLLEGE OF DERMATOLOGY Objectives Review key points of several photodermatoses Update knowledge and treatment of photodermatoses Discuss vitamin D levels in photodermatoses Types of photodermatoses Immunologically mediated disorders Defective DNA repair disorders Photoaggravated dermatoses Chemical- and drug-induced photosensitivity Types of photodermatoses Immunologically mediated disorders Polymorphous light eruption Actinic prurigo Hydroa vacciniforme Chronic actinic dermatitis Solar urticaria Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) Most common form of idiopathic photodermatitis Possibly due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an endogenous cutaneous photo- induced antigen Presents within minutes to hours of UV exposure and lasts several days Pathology Superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate Marked papillary dermal edema PMLE Treatment Topical or oral corticosteroids High SPF Restriction of UV exposure Hardening – natural, NBUVB, PUVA Antimalarial PMLE updates Study suggests topical vitamin D analogue used prophylactically may provide therapeutic benefit in PMLE Gruber-Wackernagel A, Bambach FJ, Legat A, et al. Br J Dermatol, 2011. PMLE updates Study seeks to further elucidate the pathogenesis of PMLE Found a decrease in Langerhans cells and an increase in mast cell density in lesional skin Wolf P, Gruber-Wackernagel A, Bambach I, et al. Exp Dermatol, 2014. Actinic prurigo Similar to PMLE Common in native -

Patch Testing in Adverse Drug Reactions Has Not Always Been Appreciated, but There Is Growing a Interest in This Field

24_401_412 05.11.2005 10:37 Uhr Seite 401 Chapter 24 Patch Testing 24 in Adverse Drug Reactions Derk P.Bruynzeel, Margarida Gonçalo Contents Core Message 24.1 Introduction . 401 24.2 Pathomechanisms . 403 í A drug eruption is an adverse skin reaction 24.3 Patch Test Indications . 404 caused by a drug used in normal doses 24.4 Technique and Test Materials . 406 and presents a wide variety of cutaneous reactions. 24.5 Relevance and Consequences . 407 References . 408 24.1 Introduction A drug eruption is an adverse skin reaction caused by a drug used in normal doses. Systemic exposure to drugs can lead to a wide variety of cutaneous reac- tions, ranging from erythema, maculopapular erup- tions (the most frequent reaction pattern), acrovesic- ular dermatitis, localized fixed drug eruptions, to toxic epidermal necrolysis and from urticaria to anaphylaxis (Figs. 1, 2). The incidence of these erup- tions is not exactly known; 2%–5% of inpatients ex- perience such a reaction and it is a frequent cause of consultation in dermatology [1–3]. Topically applied drugs may cause contact dermatitis reactions. Topi- cal sensitization and subsequent systemic exposure may induce dermatological patterns similar to drug eruptions or patterns more typical of a systemic con- tact dermatitis, like the “baboon syndrome” (Chap. 16). It is clear that, in these situations, patch testing can be of great help as a diagnostic tool [4]. In patients with drug eruptions without previous contact sensitization, patch testing seems less logical, but is still a strong possibility, as systemic exposure of drugs may also lead to T-cell sensitization and to delayed type IV hypersensitivity reactions [5–8]. -

Triamcinolone Acetonide Injectable Suspension, USP)

KENALOG®-10 INJECTION (triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension, USP) NOT FOR USE IN NEONATES CONTAINS BENZYL ALCOHOL For Intra-articular or Intralesional Use Only NOT FOR INTRAVENOUS, INTRAMUSCULAR, INTRAOCULAR, EPIDURAL, OR INTRATHECAL USE DESCRIPTION Kenalog®-10 Injection (triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension, USP) is triamcinolone acetonide, a synthetic glucocorticoid corticosteroid with marked anti-inflammatory action, in a sterile aqueous suspension suitable for intralesional and intra-articular injection. THIS FORMULATION IS SUITABLE FOR INTRA-ARTICULAR AND INTRALESIONAL USE ONLY. Each mL of the sterile aqueous suspension provides 10 mg triamcinolone acetonide, with 0.66% sodium chloride for isotonicity, 0.99% (w/v) benzyl alcohol as a preservative, 0.63% carboxymethylcellulose sodium, and 0.04% polysorbate 80. Sodium hydroxide or hydrochloric acid may have been added to adjust pH between 5.0 and 7.5. At the time of manufacture, the air in the container is replaced by nitrogen. The chemical name for triamcinolone acetonide is 9-Fluoro-11β,16α,17,21-tetrahydroxypregna- 1,4-diene-3,20-dione cyclic 16,17-acetal with acetone. Its structural formula is: 1 Reference ID: 4241593 MW 434.50 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Glucocorticoids, naturally occurring and synthetic, are adrenocortical steroids that are readily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. Naturally occurring glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone and cortisone), which also have salt- retaining properties, are used as replacement therapy in adrenocortical deficiency states. -

Practical Dermatology Methodical Recommendations

Vitebsk State Medical University Practical Dermatology Methodical recommendations Adaskevich UP, Valles - Kazlouskaya VV, Katina MA VSMU Publishing 2006 616.5 удк-б-1^«адл»-2о -6Sl«Sr83p3»+4£*łp30 А28 Reviewers: professor Myadeletz OD, head of the department of histology, cytology and embryology in VSMU: professor Upatov Gl, head of the department of internal diseases in VSMU Adaskevich IIP, Valles-Kazlouskaya VV, Katina МЛ. A28 Practical dermatology: methodical recommendations / Adaskevich UP, Valles-Kazlouskaya VV, Katina MA. - Vitebsk: VSMU, 2006,- 135 p. Methodical recommendations “Practical dermatology” were designed for the international students and based on the typical program in dermatology. Recommendations include tests, clinical tasks and practical skills in dermatology that arc used as during practical classes as at the examination. УДК 616.5:37.022.=20 ББК 55.83p30+55.81 p30 C Adaskev ich UP, Valles-Ka/.louskaya VV, Katina MA. 2006 OVitebsk State Medical University. 2006 Content 1. Practical skills.......................................................................................................5 > 1.1. Observation of the patient's skin (scheme of the case history).........................5 1.2. The determination of skin moislness, greasiness, dryness and turgor.......... 12 1.3. Dermographism determination.........................................................................12 1.4. A method of the arrangement of dropping and compressive allergic skin tests and their interpretation........................................................................................................ -

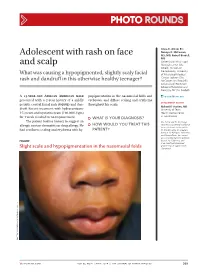

Adolescent with Rash on Face and Scalp

Photo RoUNDS Anna K. Allred, BS; Nancye K. McCowan, Adolescent with rash on face MS, MD; Robert Brodell, MD University of Mississippi and scalp Medical Center (Ms. Allred); Division of Dermatology, University What was causing a hypopigmented, slightly scaly facial of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson (Drs. rash and dandruff in this otherwise healthy teenager? McCowan and Brodell); University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, NY (Dr. Brodell) A 13-year-old African American male popigmentation in the nasomesial folds and [email protected] presented with a 2-year history of a mildly eyebrows, and diffuse scaling and erythema DEpartment EDItOR pruritic central facial rash (FIGURE) and dan- throughout his scalp. Richard p. Usatine, MD druff. Recent treatment with hydrocortisone University of Texas 1% cream and nystatin cream (100,000 U/gm) Health Science Center at San Antonio for 1 week resulted in no improvement. ● What is youR diAgnosis? The patient had no history to suggest an Ms. Allred and Dr. McCowan allergic contact dermatitis or drug allergy. He ● HoW Would you TReAT THIS reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article. had confluent scaling and erythema with hy- pATIENT? Dr. Brodell serves on speaker’s bureaus for Allergan, Galderma, and PharmaDerm, has served as a consultant and on advisory Figure boards for Galderma, and is an investigator/received grant/research support from Slight scale and hypopigmentation in the nasomesial folds Genentech. PHO T o COU RT ESY OF : R o B e RT BR ODELL , MD jfponline.com Vol 63, no 4 | ApRIL 2014 | The jouRnAl of Family PracTice 209 PHOTO RoUNDS Diagnosis: the Malassezia yeast and topical steroids are Seborrheic dermatitis used to suppress inflammation. -

DRUG-INDUCED PHOTOSENSITIVITY (Part 1 of 4)

DRUG-INDUCED PHOTOSENSITIVITY (Part 1 of 4) DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION Drug-induced photosensitivity: cutaneous adverse events due to exposure to a drug and either ultraviolet (UV) or visible radiation. Reactions can be classified as either photoallergic or phototoxic drug eruptions, though distinguishing between the two reactions can be difficult and usually does not affect management. The following criteria must be met to be considered as a photosensitive drug eruption: • Occurs only in the context of radiation • Drug or one of its metabolites must be present in the skin at the time of exposure to radiation • Drug and/or its metabolites must be able to absorb either visible or UV radiation Photoallergic drug eruption Phototoxic drug eruption Description Immune-mediated mechanism of action. Response is not dose-related. More frequent and result from direct cellular damage. May be dose- Occurs after repeated exposure to the drug dependent. Reaction can be seen with initial exposure to the drug Incidence Low High Pathophysiology Type IV hypersensitivity reaction Direct tissue injury Onset >24hrs <24hrs Clinical appearance Eczematous Exaggerated sunburn reaction with erythema, itching, and burning Localization May spread outside exposed areas Only exposed areas Pigmentary changes Unusual Frequent Histology Epidermal spongiosis, exocytosis of lymphocytes and a perivascular Necrotic keratinocytes, predominantly lymphocytic and neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate dermal infiltrate DIAGNOSIS Most cases of drug-induced photosensitivity can be diagnosed based on physical examination, detailed clinical history, and knowledge of drug classes typically implicated in photosensitive reactions. Specialized testing is not necessary to make the diagnosis for most patients. However, in cases where there is no prior literature to support a photosensitive reaction to a given drug, or where the diagnosis itself is in question, implementing phototesting, photopatch testing, or rechallenge testing can be useful. -

Chronic Pruritic Vulva Lesion

Photo RoUNDS Stephen Colden Cahill, DO Chronic pruritic vulva lesion College of Osteopathic Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing; The patient was not sexually active and denied any and Lakeshore Health vaginal discharge. So what was causing the intense Partners, Holland, Mich itching on her labia? [email protected] Department eDItOr richard p. Usatine, mD University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio During a routine exam, a 45-year-old Cau- both of her labia majora (FIGURE). Throughout casian woman complained of intense itching the lesion, there were scattered areas of exco- The author reported no potential conflict of interest on her labia. She said that the itching had been riation. Her labia minor were spared. relevant to this article. an issue for more than 9 months and that she A speculum and bimanual exam were found herself scratching several times a day. normal. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was She denied any vaginal discharge and said she present. hadn’t been sexually active in years. She had tried over-the-counter antifungals and topical ● WhaT is your diagnosis? Benadryl, but they provided only limited relief. The patient had red thickened plaques ● HoW Would you TREAT THIS with accentuated skin lines (furrows) covering PATIENT? Figure Red thickened plaques on labia majora p ho T o cour T esy of: St ephen c olden c ahill, DO jfponline.com Vol 62, no 2 | february 2013 | The journal of family pracTice 97 PHOTO RoUNDS Diagnosis: taneous lesion of unknown etiology. It can Lichen simplex chronicus be found throughout the body, including the This patient was given a diagnosis of lichen mucous membranes. -

Studies in Abnormal Human Sensitivity to Light I

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector STUDIES IN ABNORMAL HUMAN SENSITIVITY TO LIGHT I. PRTJRIGO AEST1VALIS, ECZEMA SOLARE AND URTICARIA PHOTOGENICA. REPORT OF 17CASESAND REVIEW OF THE L1TERATTJRE STEPHAN EPSTEIN, M.D.' Marshfield, Wisconsin (Received for publication May 6, 1942) Prurigo aestivalis, eczema solare and urticaria photogenica form a special group among those dermatoses which are considered as caused by light. Rela- tively little is known about them. They have received only short mention in most textbooks; few investigators have concerned themselves with experimental studies. The following is a report of clinical and experimental investigations of these conditions which will be presented in four parts. I. Clinical report. II. Experimental study of light sensitivity. III. Passive transfer in prurigo aestivalis. IV. Photoallergic concept of prurigo aestivalis. I The confusion which exists in regard to diagnosis and classification of these conditions warrants a short review of their clinical diagnosis.2 1. Prurigo aestivalis:Thiscondition, also known as chronic polymorphic light eruption, dermatopathia photogenica, erythema perstans solare, was first described by Hutchinson as summer prurigo in 1888. It is characterized by re- current eruptions of prurigo-like papules and nodules on those parts of the body which are exposed to the sunlight, face, neck, arms, hands, jugular triangle and to some extent, the lower legs (Figs. 1—3). The first symptom is burning and itching of the skin followed by erythema with more or less urticaria-like swelling. Combination with urticaria has been observed. The clinical picture is varied and may change in the same patient. -

COFP Janmar Text

B I O T E R R O R I S M PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE OF DERMATOLOGY Dr Matthew Ng Joo Ming INTRODUCTION DIAGNOSIS Medical schools and textbooks teach us The diagnosis of skin lesion is made by following dermatology by subjects such as eczema and the same general principle as in any branch of psoriasis. This is useful only for students who are medicine. The process begins by taking a history, new to dermatology. However, it has no use to the followed by a physical examination and if the practicing physician. Patient don’t come to you diagnosis is not made at this stage, further with a diagnosis but they come with a problem of investigations can be carried out. an unknown rash. HISTORY MORPHOLOGY OF SKIN LESION K Duration Characteristics morphology, pattern of K Relationship to physical agents: sun exposure, arrangement and lesions found in a particular occupation, and medication anatomical location can strongly suggest a certain K Puritis dermatological diagnosis. For example, group K Size and colour change vesicles on the penis strongly suggest a diagnosis K Family history of herpes simplex infection. A concise summation K Previous treatment of clinical features, including morphology of skin When describing skin lesion, the following should lesions, pattern of any eruption as well as symptoms be identified in turn: (e.g. itch), is helpful in arriving at a diagnosis. K Site and distribution: symmetrical, Consulting a good picture atlas of skin disease also asymmetrical aids clinical diagnosis. K Erythematous and non-erythematous Lesions can be grouped into four distinct K Surface characteristics: smooth, scaly, warty patterns: linear, annular, group and reticular.