For Peer Review Onlyemail: [email protected] 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetics, Comparative Parasitology, and Host Affinities of Chipmunk Sucking Lice and Pinworms Kayce Bell

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2016 Coevolving histories inside and out: phylogenetics, comparative parasitology, and host affinities of chipmunk sucking lice and pinworms Kayce Bell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Recommended Citation Bell, Kayce. "Coevolving histories inside and out: phylogenetics, comparative parasitology, and host affinities of chipmunk sucking lice and pinworms." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/120 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kayce C. Bell Candidate Department of Biology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph A. Cook , Chairperson Dr. John R. Demboski Dr. Irene Salinas Dr. Kenneth Whitney Dr. Jessica Light i COEVOLVING HISTORIES INSIDE AND OUT: PHYLOGENETICS, COMPARATIVE PARASITOLOGY, AND HOST AFFINITIES OF CHIPMUNK SUCKING LICE AND PINWORMS by KAYCE C. BELL B.S., Biology, Idaho State University, 2003 M.S., Biology, Idaho State University, 2006 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2016 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of my degree and this dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support of my mentors, family, and friends. Dr. Joseph Cook first introduced me to phylogeography and parasites as undergraduate and has proven time and again to be the best advisor a graduate student could ask for. -

Full Proposal

FUNDING APPLICATION FOR YOUNG RESEARCH TEAMS - PN-II-RU-TE-2014-4 This document uses Times New Roman font, 12 point, 1.5 line spacing and 2 cm margins. Any modification of these parameters (excepting the figures and their captions), as well as exceeding the maximum number of pages set for each section will lead to the automatic disqualification of the application. The imposed number of pages does not contain the references; these will be written on additional pages. The black text must be kept, as it marks the mandatory information and sections of the application. CUPRINS B. Project leader ................................................................................................................................. 3 B1. Important scientific achievements of the project leader ............................................................ 3 B2. Curriculum vitae ........................................................................................................................ 5 B3. Defining elements of the remarkable scientific achievements of the project leader ................. 7 B3.1 The list of the most important scientific publications from 2004-2014 period ................... 7 B3.2. The autonomy and visibility of the scientific activity. ....................................................... 9 C.Project description ....................................................................................................................... 11 C1. Problems. ................................................................................................................................ -

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (Takım Düzeyinde)

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (TAKIM DÜZEYİNDE) GÖKHAN AYDIN 2016 Editör : Gökhan AYDIN Dizgi : Ziya ÖNCÜ ISBN : 978-605-87432-3-6 Böceklerin Sınıflandırılması isimli eğitim amaçlı hazırlanan bilgisayar programı için lütfen aşağıda verilen linki tıklayarak programı ücretsiz olarak bilgisayarınıza yükleyin. http://atabeymyo.sdu.edu.tr/assets/uploads/sites/76/files/siniflama-05102016.exe Eğitim Amaçlı Bilgisayar Programı ISBN: 978-605-87432-2-9 İçindekiler İçindekiler i Önsöz vi 1. Protura - Coneheads 1 1.1 Özellikleri 1 1.2 Ekonomik Önemi 2 1.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 2 2. Collembola - Springtails 3 2.1 Özellikleri 3 2.2 Ekonomik Önemi 4 2.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 4 3. Thysanura - Silverfish 6 3.1 Özellikleri 6 3.2 Ekonomik Önemi 7 3.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 7 4. Microcoryphia - Bristletails 8 4.1 Özellikleri 8 4.2 Ekonomik Önemi 9 5. Diplura 10 5.1 Özellikleri 10 5.2 Ekonomik Önemi 10 5.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 11 6. Plocoptera – Stoneflies 12 6.1 Özellikleri 12 6.2 Ekonomik Önemi 12 6.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 13 7. Embioptera - webspinners 14 7.1 Özellikleri 15 7.2 Ekonomik Önemi 15 7.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 15 8. Orthoptera–Grasshoppers, Crickets 16 8.1 Özellikleri 16 8.2 Ekonomik Önemi 16 8.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 17 i 9. Phasmida - Walkingsticks 20 9.1 Özellikleri 20 9.2 Ekonomik Önemi 21 9.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 21 10. Dermaptera - Earwigs 23 10.1 Özellikleri 23 10.2 Ekonomik Önemi 24 10.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 24 11. Zoraptera 25 11.1 Özellikleri 25 11.2 Ekonomik Önemi 25 11.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 26 12. -

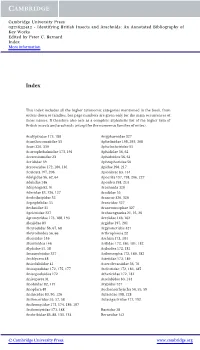

Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: an Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C

Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. Barnard Index More information Index This index includes all the higher taxonomic categories mentioned in the book, from orders down to families, but page numbers are given only for the main occurrences of those names. It therefore also acts as a complete alphabetic list of the higher taxa of British insects and arachnids (except for the numerous families of mites). Acalyptratae 173, 188 Anyphaenidae 327 Acanthosomatidae 55 Aphelinidae 198, 293, 308 Acari 320, 330 Aphelocheiridae 55 Acartophthalmidae 173, 191 Aphididae 56, 62 Acerentomidae 23 Aphidoidea 56, 61 Acrididae 39 Aphrophoridae 56 Acroceridae 172, 180, 181 Apidae 198, 217 Aculeata 197, 206 Apioninae 83, 134 Adelgidae 56, 62, 64 Apocrita 197, 198, 206, 227 Adelidae 146 Apoidea 198, 214 Adephaga 82, 91 Arachnida 320 Aderidae 83, 126, 127 Aradidae 55 Aeolothripidae 52 Araneae 320, 326 Aepophilidae 55 Araneidae 327 Aeshnidae 31 Araneomorphae 327 Agelenidae 327 Archaeognatha 21, 25, 26 Agromyzidae 173, 188, 193 Arctiidae 146, 162 Alexiidae 83 Argidae 197, 201 Aleyrodidae 56, 67, 68 Argyronetidae 327 Aleyrodoidea 56, 66 Arthropleona 22 Alucitidae 146 Aschiza 173, 184 Alucitoidea 146 Asilidae 172, 180, 181, 182 Alydidae 55, 58 Asiloidea 172, 181 Amaurobiidae 327 Asilomorpha 172, 180, 182 Amblycera 48 Asteiidae 173, 189 Anisolabiidae 41 Asterolecaniidae 56, 70 Anisopodidae 172, 175, 177 Atelestidae 172, 183, 185 Anisopodoidea 172 Athericidae 172, 181 Anisoptera 31 Attelabidae 83, 134 Anobiidae 82, 119 Atypidae 327 Anoplura 48 Auchenorrhyncha 54, 55, 59 Anthicidae 83, 90, 126 Aulacidae 198, 228 Anthocoridae 55, 57, 58 Aulacigastridae 173, 192 Anthomyiidae 173, 174, 186, 187 Anthomyzidae 173, 188 Baetidae 28 Anthribidae 83, 88, 133, 134 Beraeidae 142 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. -

The Mitochondrial Genome of the Guanaco Louse, Microthoracius Praelongiceps: Insights Into the Ancestral Mitochondrial Karyotype of Sucking Lice (Anoplura, Insecta)

GBE The Mitochondrial Genome of the Guanaco Louse, Microthoracius praelongiceps: Insights into the Ancestral Mitochondrial Karyotype of Sucking Lice (Anoplura, Insecta) Renfu Shao1,*, Hu Li2, Stephen C. Barker3, and Simon Song1,* 1GeneCology Research Centre, School of Science and Engineering, Faculty of Science, Health, Education and Engineering, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, Queensland, Australia 2Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China 3Parasitology Section, School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia *Corresponding authors: E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]. Accepted: January 31, 2017 Data deposition: The nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial genome of the guanaco louse, Microthoracius praelongiceps, has been deposited at GenBank (accession numbers KX090378–KX090389). Abstract Fragmented mitochondrial (mt) genomes have been reported in 11 species of sucking lice (suborder Anoplura) that infest humans, chimpanzees, pigs, horses, and rodents. There is substantial variation among these lice in mt karyotype: the number of minichromo- somes of a species ranges from 9 to 20; the number of genes in a minichromosome ranges from 1 to 8; gene arrangement in a minichromosome differs between species, even in the same genus. We sequenced the mt genome of the guanaco louse, Microthoracius praelongiceps, to help establish the ancestral mt karyotype for sucking lice and understand how fragmented mt genomes evolved. The guanaco louse has 12 mt minichromosomes; each minichromosome has 2–5 genes and a non-coding region. The guanaco louse shares many features with rodent lice in mt karyotype, more than with other sucking lice. The guanaco louse, however, is more closely related phylogenetically to human lice, chimpanzee lice, pig lice, and horse lice than to rodent lice. -

Insecta: Psocodea: 'Psocoptera'

Molecular systematics of the suborder Trogiomorpha (Insecta: Title Psocodea: 'Psocoptera') Author(s) Yoshizawa, Kazunori; Lienhard, Charles; Johnson, Kevin P. Citation Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 146(2): 287-299 Issue Date 2006-02 DOI Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/43134 The definitive version is available at www.blackwell- Right synergy.com Type article (author version) Additional Information File Information 2006zjls-1.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKZOJZoological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4082The Lin- nean Society of London, 2006? 2006 146? •••• zoj_207.fm Original Article MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF THE SUBORDER TROGIOMORPHA K. YOSHIZAWA ET AL. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2006, 146, ••–••. With 3 figures Molecular systematics of the suborder Trogiomorpha (Insecta: Psocodea: ‘Psocoptera’) KAZUNORI YOSHIZAWA1*, CHARLES LIENHARD2 and KEVIN P. JOHNSON3 1Systematic Entomology, Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Sapporo 060-8589, Japan 2Natural History Museum, c.p. 6434, CH-1211, Geneva 6, Switzerland 3Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820, USA Received March 2005; accepted for publication July 2005 Phylogenetic relationships among extant families in the suborder Trogiomorpha (Insecta: Psocodea: ‘Psocoptera’) 1 were inferred from partial sequences of the nuclear 18S rRNA and Histone 3 and mitochondrial 16S rRNA genes. Analyses of these data produced trees that largely supported the traditional classification; however, monophyly of the infraorder Psocathropetae (= Psyllipsocidae + Prionoglarididae) was not recovered. Instead, the family Psyllipso- cidae was recovered as the sister taxon to the infraorder Atropetae (= Lepidopsocidae + Trogiidae + Psoquillidae), and the Prionoglarididae was recovered as sister to all other families in the suborder. -

Psocodea, “Psocoptera”, Psocidae), with One New Species

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeysA review 203: 27–46 of the(2012) genus Neopsocopsis (Psocodea, “Psocoptera”, Psocidae), with one new species... 27 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.203.3138 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A review of the genus Neopsocopsis (Psocodea, “Psocoptera”, Psocidae), with one new species from China Lu-Xi Liu1,†, Kazunori Yoshizawa2,‡, Fa-Sheng Li1,§, Zhi-Qi Liu1,| 1 Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 100193, China 2 Systematic Entomo- logy, Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, 060-8589, Japan † urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:192B5D2C-88C9-41A6-95B5-C6F992B2573B ‡ urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:E6937129-AF09-4073-BABF-5C025930BF31 § urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:46BA87D8-F520-4E04-B72A-87901DAFB46E | urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A642446F-B2A9-409F-A3D4-0C882890B846 Corresponding author: Zhi-Qi Liu ([email protected]) Academic editor: Vincent Smith | Received 29 March 2012 | Accepted 6 June 2012 | Published 19 June 2012 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:45CC60D2-0723-4177-A271-451D933B8D87 Citation: Liu L-X, Yoshizawa K, Li F-S, Liu Z-Q (2012) A review of the genus Neopsocopsis (Psocodea, “Psocoptera”, Psocidae), with one new species from China. ZooKeys 203: 27–46. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.203.3138 Abstract A review of species of the genus Neopsocopsis Badonnel, 1936 is presented. Four species are redescribed, viz. N. hirticornis (Reuter, 1893), N. quinquedentata (Li & Yang, 1988), N. profunda (Li, 1995), and N. flavida (Li, 1989), as well as the description of one new species, N. convexa sp. n. Seven new synonymies are proposed as follows: Pentablaste obconica Li syn. -

Psocoptera Em Cavernas Do Brasil: Riqueza, Composição E Distribuição

PSOCOPTERA EM CAVERNAS DO BRASIL: RIQUEZA, COMPOSIÇÃO E DISTRIBUIÇÃO THAÍS OLIVEIRA DO CARMO 2009 THAÍS OLIVEIRA DO CARMO PSOCOPTERA EM CAVERNAS DO BRASIL: RIQUEZA, COMPOSIÇÃO E DISTRIBUIÇÃO Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Lavras, como parte das exigências do programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia Aplicada, área de concentração em Ecologia e Conservação de Paisagens Fragmentadas e Agroecossistemas, para obtenção do título de “Mestre”. Orientador Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira LAVRAS MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL 2009 Ficha Catalográfica Preparada pela Divisão de Processos Técnicos da Biblioteca Central da UFLA Carmo, Thaís Oliveira do. Psocoptera em cavernas do Brasil: riqueza, composição e distribuição / Thaís Oliveira do Carmo. – Lavras : UFLA, 2009. 98 p. : il. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Lavras, 2009. Orientador: Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira. Bibliografia. 1. Insetos cavernícolas. 2. Ecologia. 3. Diversidade. 4. Fauna cavernícola. I. Universidade Federal de Lavras. II. Título. CDD – 574.5264 THAÍS OLIVEIRA DO CARMO PSOCOPTERA EM CAVERNAS DO BRASIL: RIQUEZA, COMPOSIÇÃO E DISTRIBUIÇÃO Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Lavras, como parte das exigências do programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia Aplicada, área de concentração em Ecologia e Conservação de Paisagens Fragmentadas e Agroecossistemas, para obtenção do título de “Mestre”. APROVADA em 04 de dezembro de 2009 Prof. Dr. Marconi Souza Silva UNILAVRAS Prof. Dr. Luís Cláudio Paterno Silveira UFLA Prof. Dr. Rodrigo Lopes Ferreira UFLA (Orientador) LAVRAS MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL ...Então não vá embora Agora que eu posso dizer Eu já era o que sou agora Mas agora gosto de ser (Poema Quebrado - Oswaldo Montenegro) AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus, pois com Ele nada nessa vida é impossível! Agradeço aos meus pais, Joaquim e Madalena, pela oportunidade e apoio. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Elephant Bibliography Elephant Editors

Elephant Volume 2 | Issue 3 Article 17 12-20-1987 Elephant Bibliography Elephant Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/elephant Recommended Citation Shoshani, J. (Ed.). (1987). Elephant Bibliography. Elephant, 2(3), 123-143. Doi: 10.22237/elephant/1521732144 This Elephant Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Elephant by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Fall 1987 ELEPHANT BIBLIOGRAPHY: 1980 - PRESENT 123 ELEPHANT BIBLIOGRAPHY With the publication of this issue we have on file references for the past 68 years, with a total of 2446 references. Because of the technical problems and lack of time, we are publishing only references for 1980-1987; the rest (1920-1987) will appear at a later date. The references listed below were retrieved from different sources: Recent Literature of Mammalogy (published by the American Society of Mammalogists), Computer Bibliographic Search Services (CCBS, the same used in previous issues), books in our office, EIG questionnaires, publications and other literature crossing the editors' desks. This Bibliography does not include references listed in the Bibliographies of previous issues of Elephant. A total of 217 new references has been added in this issue. Most of the references were compiled on a computer using a special program developed by Gary L. King; the efforts of the King family have been invaluable. The references retrieved from the computer search may have been slightly altered. These alterations may be in the author's own title, hyphenation and word segmentation or translation into English of foreign titles. -

THE LIFE HISTORY and COMPARATIVE INFESTATIONS of POLYPLAX SPINULOSA (BURMEISTER) on NORMAL and RIBOFLAVIN-DEFICIENT RATS : Prese

THE LIFE HISTORY AND COMPARATIVE INFESTATIONS OF POLYPLAX SPINULOSA (BURMEISTER) ON NORMAL AND RIBOFLAVIN-DEFICIENT RATS dissertation : Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University 3y DEFIELD TROLLINGER HOLMES,, B. Sc., M; Sc. The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by BriLd: Adviser Department of Zoology and Entomology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS X would like to make special acknowledgment to my adviser, Dr. C. E. Venard, Department of Zoology and Entomology, The Ohio State University, for his understanding encouragement and oontlnued assistance and stimulation throughout this research. Thanks are also due to Dr. D. M. DeLong and Dr. F. W. Fisk, also of this department, for the contribution of materials when needed; to Mr. Fhelton Simmons of the Columbus Health Department for kindly contributing rats from various areas In Columbus; to Mr. William W. Barnes and Mr. Roger Meola for technical assistance. Finally, I wish to express sincere appreciation to my wife, Ophelia, for her patience and enoouragement throughout this research and for her aid In the preparation and typing of this material. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pag© Introduction .............................................. 1 Historical Review and Taxonomy .................. .... 6 Materials and Methods .....................................14 Life History ........................... .22 Incubation Period of the E g g ....................... 23 First Stage Nymph ....................................26 Second -

Pacific Insects Four New Species of Gyropidae

PACIFIC INSECTS Vol. ll, nos. 3-4 10 December 1969 Organ of the program ' 'Zoogeography and Evolution of Pacific Insects." Published by Entomology Department, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii, U. S. A. Editorial committee: J. L. Gressitt (editor), S. Asahina, R. G. Fennah, R. A. Harrison, T. C. Maa, CW. Sabrosky, J. J. H. Szent-Ivany, J. van der Vecht, K. Yasumatsu and E. C. Zimmerman. Devoted to studies of insects and other terrestrial arthropods from the Pacific area, includ ing eastern Asia, Australia and Antarctica. FOUR NEW SPECIES OF GYROPIDAE (Mallophaga) FROM SPINY RATS IN MIDDLE AMERICA By Eustorgio Mendez1 Abstract: The following new species of biting lice from mammals are described and figured: Gyropus emersoni from Proechimys semispinosus panamensis, Panama; G. meso- americanus from Hoplomys gymnurus truei, Nicaragua; Gliricola arboricola from Diplomys labilis, Panama; G. sylvatica from Hoplomys gymnurus, Panama. The spiny rat family Echimyidae evidently is one of the rodent groups which is more favored by Mallophaga. Members of several genera belonging to two Amblyceran families of biting lice (Gyropidae and Trimenoponidae) are known to parasitize spiny rats. The present contribution adds to the knowledge of the Mallophagan fauna of these neotropi cal rodents two species each of Gyropus and Gliricola (Gyropidae). My gratitude is expressed to Dr K. C. Emerson, who furnished most of the material used in this study. He also invited me to describe the first two species here treated and critically read the manuscript. The specimens of Gyropus mesoamericanus n. sp., kindly submitted for description by Dr J. Knox Jones Jr., were collected under contract (DA-49-193-MD-2215) between the U.