7608336.PDF (7.065Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to the 1645 Volume: Poems of Mr. John Milton

C01.qxd 8/18/08 14:44 Page 1 Introduction to the 1645 Volume: Poems of Mr. John Milton In 1645, Milton published most but not all of the poems he had composed by that date. The publisher Humphrey Moseley had been bringing out volumes of lyric poetry by royalist poets such as Edmund Waller, and it was likely, as he claims in the intro- duction to the volume, that he approached Milton and encouraged him to publish his verse. Moseley also arranged for the engraved portrait of Milton by William Marshall (see Figure 1), beneath which Milton, who considered the engraving unflattering, placed a witty Greek epigram ridiculing it in a language neither Marshall nor Moseley under- stood. Unlike most contemporary poets, Milton neither wrote a preface, solicited commendatory poems, nor acknowledged a patron. He organized his volume more or less chronologically, thus displaying his poetic development, but also carefully grouped together poems of similar themes and genres. With the Latin tag from Virgil’s Eclogues on the title page (“Baccare frontem / Cingite, ne vati noceat mala lingua futuro” – “Bind my forehead with foxglove, lest evil tongues harm the future Bard”), he promises future poems on even greater themes. In the Latin ode sent with a replacement copy of the volume to John Rouse, librar- ian of the Bodleian Library at Oxford, Milton describes the 1645 volume as a “twin book, rejoicing in a single cover, but with a double title page.” The first section of the volume presents his vernacular poems (mostly in English, but also including a mini-sonnet sequence in Italian), and concludes with A MASK Presented At LUDLOW- Castle. -

Edward Jones

Edward Jones Events in John Milton’s life Events in Milton’s time JM is born in Bread Street (Dec 9) 1608 Shakespeare’s Pericles debuts to and baptized in the church of All great acclaim. Hallows, London (Dec 20). Champlain founds a colony at Quebec. 1609 Shakespeare’s Cymbeline is performed late in the year or in the first months of 1610, most likely indoors at the Blackfriars Theatre. The British establish a colony in Bermuda. Moriscos (Christianized Muslims) are expelled from Spain. Galileo constructs his first telescope. The Dutch East India Company ships the first tea to Europe. A tax assessment (E179/146/470) 1610 Galileo discovers the four largest confirms the Miltons residing in moons of Jupiter (Jan 7). the parish of All Hallows, London Ellen Jeffrey, JM’s maternal 1611 Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale is grandmother, is buried in All performed at the Globe Theatre Hallows, London (Feb 26). (May). The Authorized Version (King James Bible) is published. Shakespeare’s The Tempest is performed at court (Nov 1). The Dutch begin trading with Japan. The First Presbyterian Congregation is established at Jamestown. JM’s sister Sara is baptized (Jul 15) 1612 Henry, Prince of Wales, dies. and buried in All Hallows, London Charles I becomes heir to the (Aug 6). throne. 1613 A fire breaks out during a performance of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII and destroys the Globe Theatre (Jun 29). 218 Select Chronology Events in John Milton’s life Events in Milton’s time JM’s sister Tabitha is baptized in 1614 Shakespeare’s Two Noble Kinsmen All Hallows, London (Jan 30). -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Rosentene Bennett Purnell 1967

This dissertation has been microiihned exactly as received 67-11,478 PURNELL, Rosentene Bennett, 1933- JOHN MILTON AND THE DOCTRINE OF SYMPATHY; DEONTOLOGY AND AMBIANCE. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D„ 1967 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Rosentene Bennett Purnell 1967. All Rights Reserved THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JOHN MILTON AND THE DOCTRINE OF SYMPATHY: DEONTOLOGY AND AMBIANCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ROSENTENE BENNETT PURNELL Norman, Oklahoma 1967 JOHN MILTON AND THE DOCTRINE OF SYMPATHY: DEONTOLOGY AND AMBIANCE APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE 5o mij éetoved parents ^M,r. and <SKrs. Utorace benjam in 'Bennett to ivfiom S owe ai( that S am or ever iiope to ée and Uke ’^partner oj mif iije/ ¥rank '"Deiano Ÿurneit ACKNOWLEDGMENT My debts are great, as is my gratitude, for the generous help proffered from many sources during my doctoral study at the University of Oklahoma, and specifically, during the preparation of this dissertation. To Dr. David S. Berkeley, Oklahoma State University, I am grateful for the beginning and deepening of my interest in Milton. His en thusiasm and encouragement inspired me to pursue further the idea of sympathy in Milton, the inception of which was in his Milton course here at the University of Oklahoma. I wish to thank.the entire Department of English for its many contributions to my growth, both as a student and as a member of the staff. To the members of my committee: Dr. -

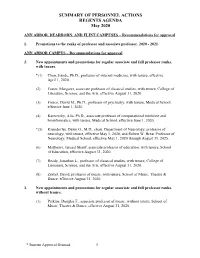

May 2020 Personnel Actions

SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR, DEARBORN, AND FLINT CAMPUSES – Recommendations for approval 1. Promotions to the ranks of professor and associate professor, 2020 - 2021. ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 2. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, with tenure. *(1) Chen, Jiande, Ph.D., professor of internal medicine, with tenure, effective April 1, 2020. (2) Foster, Margaret, associate professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (3) Fresco, David M., Ph.D., professor of psychiatry, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. (4) Karnovsky, Alla, Ph.D., associate professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. *(5) Kleindorfer, Dawn O., M.D., chair, Department of Neurology, professor of neurology, with tenure, effective May 1, 2020, and Robert W. Brear Professor of Neurology, Medical School, effective May 1, 2020 through August 31, 2025. (6) Matthews, Jamaal Sharif, associate professor of education, with tenure, School of Education, effective August 31, 2020. (7) Ready, Jonathan L., professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (8) Zerkel, David, professor of music, with tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. 3. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, without tenure. (1) Perkins, Douglas F., associate professor of music, without tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. * Interim Approval Granted 1 SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 4. -

Israël Veut Un « Changement Complet » De La Politique Menée Par L'olp

LeMonde Job: WMQ0208--0001-0 WAS LMQ0208-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 01-08-97 T.: 11:23 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:01,11, Base : LMQPAG 27Fap:99 No:0328 Lcp: 196 CMYK CINQUANTE-TROISIÈME ANNÉE – No 16333 – 7,50 F SAMEDI 2 AOÛT 1997 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Les athlètes Israël veut un « changement complet » à Athènes de la politique menée par l’OLP Rigor Mortis a Brigitte Aubert Participation record Benyamin Nétanyahou exige de Yasser Arafat qu’il éradique le terrorisme a aux championnats ISRAÉLIENS et responsables de Jérusalem. Les premiers accusent Le premier ministre a mis Yasser maine. « On ne peut faire avancer du monde l’Autorité palestinienne se sont l’OLP de ne pas en faire assez dans Arafat en demeure d’éradiquer le le processus diplomatique alors que renvoyés, jeudi 31 juillet, la res- la lutte contre le terrorisme ; les terrorisme et a juré qu’il n’y aurait l’Autorité palestinienne ne prend une nouvelle inédite ponsabilité de l’attentat qui, la seconds affirment que la politique pas de reprise des conversations pas les mesures minimales qu’elle qui s’ouvrent samedi veille, a fait quinze morts et plus du gouvernement de Benyamin israélo-palestiniennes tant qu’Is- s’est engagée à prendre contre les de cent cinquante blessés sur un Nétanyahou favorise la montée raël ne jugerait pas l’action de foyers du terrorisme », a dit M. Né- dames a des marchés les plus populaires de des extrémistes palestiniens. l’OLP satisfaisante dans ce do- tanyahou. « Il faut un changement du noir La pollution peut complet de politique de la part des Palestiniens, une campagne vigou- perturber les épreuves reuse, systématique et immédiate pour éliminer le terrorisme », a-t-il Les Dames a lancé, jeudi soir, à la télévision. -

Download M51 Redux.Pdf

I MILTON (ANDREW FLETCHER, Lord). See FLiT'CHER (ANDREW) Lord Milton. MILTON (CHARLES WILLIAM Wi TWOR'TH FITZWILLIAM, Viscount). See FITZWILLIAM (CHARLES WILLIAM WENTWORTH FITZWILLIAM, 5th Earl). MILTON (GEORGE FORT). - -- Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth Column. [Collier Bks. AS 204.1 New York, 1962. .9(73785-86) Lin. Mil. - -- The eve of conflict; Stephen A. Douglas and the needless war. Boston, 1934 .9(736) Dou. Mil. - -- The use of presidential power, 1789 -1943. Repr. Boston, 1945 .35303 Mil. MILTON (HENRY). - -- Letters on the fine arts, written from Paris, in ... 1815. Lond., 1816. Bound in V.17.42. Al)l)17'lUNS MILTON (CATHERINE HIGGS). - -- joint- author. Police use of deadly force. See POLICE USE OF DEADLY FORCE. - -- joint- author. Women in policing; a manual. See WOMEN IN POLICING; ... -- See SHERMAN (LAWRENCE W.), M. (C.H.) and KELLY (THOMAS V.). MILTON (DEREK). --- The rainfall from tropical cyclones in Western Australia. See GEOWEST. No. 13. MILTON (J.R.L.). --- Statutory offences ... See SOUTH AFRICAN CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE. Vol. 3. MILTON (JOHN). ARRANGEMENT Collections 1. General 2. Poetry 3. Prose Correspondence Accidence L'allegro and Il penseroso Animadversions upon the remonstrant's defence Arcades Areopagitica Artis logicae plenior institutio Brief history of Moscovia Brief notes on a late sermon titl'd The fear of God and the King Commonplace book Cornus De doctrina Christiana Doctrine and discipline of divorce Eikonoklastes Epitaph on Shakespeare. See On Shakespeare Epitaphium Damons History of Britain Lycidas Of education Of reformation touching church discipline On Shakespeare [Continued overleaf.] MILTON (JOHN) [continued]. ARRANGEMENT [continued] Paradise lost Paradise regained Il penseroso. -

Punctuation of Verse

Punctuating quotations American typographic convention calls for commas and periods to come before the final, closing quotation mark, not after. Note proper usage around poem titles. not. The messages of “On the University Carrier”, “Another on the Same”, and “On Shakespeare” are clear to careful readers. The messages of “On the University Carrier,” “Another on the Same,” and “On Shakespeare” are clear to careful readers. not. Milton broaches the issue of death in several of his early poems including “On the Death of a Fair Infant”, “On Shakespeare”, “On the University Carrier”, and “Another on the S a m e”. Milton broaches the issue of death in several of his early poems including “On the Death of a Fair Infant,” “On Shakespeare,” “On the University Carrier,” and “Another on the Same.”1 • The titles “On Time” and “On the University Carrier” are placed in quotation marks, but Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained are formatted with italics. Titles of works published in collections, thus most poems titles, are typically placed in quotation marks. Titles of full-length works are formatted with italics. • When quoting, the simplest form of MLA citation places the author’s name and an appropriate page number inside a parenthetical citation. Punctuation follows the citation. Chapter four of Tales and Towns of Northern New Jersey opens with the remark: “I don’t remember just when it was that I first 1 Notice the terminal comma before and. The necessity of its use is debated. Whether you choose to employ it or not, make sure that your sentences are clear. -

The Dramaturgy of Marivaux: Three Elements of Technique

72-4653 SPINELLI, Donald Carmen, 1942- THE DRAMATURGY OF MARIVAUX: THREE ELEMENTS OF TECHNIQUE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms,A XE R O X Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © 1 9 7 1 Donald Carmen Spinelli ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE DRAMATURGY OF MARIVAUX* THREE ELEMENTS OF TECHNIQUE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donald C. Spinelli, B.A., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by Adviser nt of Romance Languages PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have Indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS TO MY MOTHER AND FATHER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to some of the people who have made this work possible. Professors Pierre Aubery and V. Frederick Koenig took a personal interest in my academic progress while I was at the University of Buffalo and both en couraged me to continue my studies in French, At Ohio State University I am grateful to my ad visor* Professor Hugh M. Davidson* whose seminar first interested me in Marivaux. Professor Davidson*s sound advice* helpful comments* clarifying suggestions and tactful criticism while discussing the manuscript gave direction to this study and were invaluable in bringing it to its fruition. 1 must thank Emily Cronau who often gave of her own time to type and to help edit this dissertation! but most of all I am grateful for her just being there when she was needed during the past few years. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography Poems of Mr John Milton: the 1645 Edition with Essays in Analysis, ed. Cleanth Brooks and John E. Hardy (Harcourt, Brace, 1951). Milton's L ycidas: the Tradition and the Poem, ed. C. A. Patrides (Holt, Rinehart, 1961). Milton: Modern Essays in Criticism, ed. Arthur E. Barker (Oxford U.P., 1965). Rosemond Tuve, Images and Themes in Five Poems by 1Uilton (Harvard U.P., 1957; Oxford U.P., 1958). The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands, ed. Frank Kermode (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1960; paperback, 1963). Anne D. Ferry, Milton's Epic Voice: the Narrator in Paradise Lost (Harvard U.P., 1963; Oxford U.P., 1963). C. S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (Oxford U.P., 1942; paperback, 1960). Arnold Stein, Answerable Style: Essays on Paradise Lost (University of Minnesota P., 1953; Oxford U.P., 1953). Joseph H. Summers, The Muse's Method: an Introduction to Paradise Lost (Harvard U.P., 1962; Chatto & Windus, 1962). A.J. A. Waldock, Paradise Lost and its Critics (Cambridge U.P., 1947; paperback, 1962; Peter Smith, 1962). B. A. Wright, Milton's Paradise Lost: a Reassessment of the Poem (Methuen, 1962; Barnes & Noble, 1962). Christopher B. Ricks, Milton's Grand Style: A Study of Paradise Lost (Clarendon P., 1963). Stanley E. Fish, Surprised by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost (Macmillan, 1967; StMartin's Press, 1967). Arnold Stein, Heroic Knowledge: An Interpretation of Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes (University of Minnesota P., 1957; Oxford U.P., 1957). M. M. Mahood, Poetry and Humanism (Yale U.P., 1950; Jonathan Cape, 1950). F. T. -

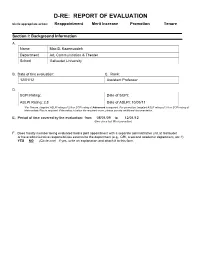

Report of Evaluation

D-RE: REPORT OF EVALUATION Circle appropriate action: Reappointment Merit Increase Promotion Tenure Section I: Background Information A. Name Max B. Kazemzadeh Department Art, Communication & Theater School Gallaudet University B. Date of this evaluation: C. Rank: 12/01/12 Assistant Professor D. SCPI Rating: Date of SCPI: ASLPI Rating: 2.8 Date of ASLPI: 10/05/11 *For Tenure, targeted ASLPI rating of 2.5 or SCPI rating of Advanced is required. For promotion, targeted ASLP rating of 3.0 or SCPI rating of Intermediate Plus is required. If the rating is below the required score, please provide additional documentation. E. Period of time covered by the evaluation: from _08/01/09_ to __12/01/12__ (time since last MI or promotion) F. Does faculty member being evaluated hold a joint appointment with a separate administrative unit at Gallaudet or have administrative responsibilities external to the department (e.g., GRI, a second academic department, etc.?) YES NO (Circle one) If yes, write an explanation and attach it to this form. Section II: Teaching From UF Guidelines, Section 2.1.2.1: Teaching competence includes both expertise in the faculty member's field and the ability to impart knowledge deriving from that field to Gallaudet students. A competent teacher must possess the ability to communicate course content clearly and effectively; he/she must also be available to the students individually, responsive to their academic needs, and flexible enough to adapt curriculum and methodology to those needs. [Effective communication as intended by this heading is separate from and in addition to proficiency in Sign Communication as outlined in Section 2.1.2.4.] A. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 25,1905-1906, Trip

INFANTRY HALL, PROVIDENCE. BostonSympIiQnu Dictiestra WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor. Twenty-fifth Season, 1905-1906. PROGRAMME OF THE FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 2, AT 8.15. Hale. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by Philip Published by C. A. ELLIS, Manager, l A PIANO FOR THE MUSICALLY INTELLIGENT artists' pianos f| Pianos divide into two classes, and popular pianos. The proportion of the first class to the second class is precisely the proportion of cultivated music lovers to the rest of society. A piano, as much as a music library, is the index of the musical taste of its owner. are among the musically intelligent, the ^f If you PIANO is worth your study. You will appreciate the " theory and practice of its makers : Let us have an artist's piano ; therefore let us employ the sci- ence, secure the skill, use the materials, and de- vote the time necessary to this end. Then let us count the cost and regulate the -price" \ In this case hearing, not seeing, is believing. Let us send you a list of our branch houses and sales agents (located in all important cities), at whose warerooms our pianos may be heard. fllnsmt&ijermlh Boston, Mass., 492 Boylston Street New York, 139 Fifth Avenue Chicago, Wabash Avenue and Jackson Boulevard . Boston Symphony Orchestra. PERSONNEL. Twenty=fifth Season, 1905-1906. WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor First Violins. Hess, Willy, Concertmeister. Adamowski, T. Ondricek, K. Mahn, F Back, A. Roth, O. Krafft, W. Eichheim, H. Sokoloff, N. Kuntz, D. Hoffmann, J. Fiedler, E. Mullaly, J. Moldauer, A. Strube, G. Rissland, K. -

Bibliography

Bibliography MANUSCRll'TS' (INCLUDING BOOKS WITH MANUSCRll'T ANNOTAnONS) Amsterdam, Universiteits-Bibliotheek MS ill.E.9 (letters from Nicolas Heinsius to Isaac Vossius) Austin, Harry Ranson Humanities Research Center Pre-1700 Manuscript 127 (see 1615) Austin, University of Texas Library Milton, John, Defensio Pro Populo Anglicano (1651) (see 24 Febru ary 1651) Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire County Record Office DAT 107 Horton, Bishop's Transcript, 1637 PR 10711/1 (Horton Parish Register) Bedford, Bedfordshire Record Office MS Pl1/28/2 (see 24 June 1695) Bloomington, Lilly Library, Indiana University George Sikes, The Life and Death of Sir Henry Vane (see 5 Septem ber 1662) Boston, Massachusetts Historical Society , Winthrop Papers Boulder, Colorado University Library Leo Miller Collection Box XXII, File 17 (Leo Miller, 'Milton in Geneva and the significance of the Cardoini Album') Brussels, Bibliotheque Royale MS II 4109 Mus. Fetis 3095 (a collection of 100 songs in the hand of Thomas Myriell) Cambridge, Christ's College Admissions Book MS 8 ('Milton Autographs') Cambridge, Trinity College MS R.3.4 (JM's workbook) MS R.5.5 (Anne Sadleir's letterbook) MS 0.ii.68 (MS copy of John Lane's Triton's Trumpet) JM, Eikonoklastes (C.9.179; see 19 June 1650) Cambridge University Library Justa Edouardo King 1638 (Add MS 154); annotated by JM University Archives 233 234 A Milton Chronology Matriculation Book Subscription Book Supplicats 1627, 1628, 1629 Supplicats 1630, 1631, 1632 Canterbury, Cathedral Library JM, Eikonoklastes (Elham 732); See. 11