The Dramaturgy of Marivaux: Three Elements of Technique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Renaissance Dream Theory and Its Use in Shakespeare

THE RICE INSTITUTE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE DREAM THEORY MID ITS USE IN SHAKESPEARE By COMPTON REES, JUNIOR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Houston, Texas April, 1958 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............. 1-3 Chapter I Psychological Background: Imagination and Sleep ............................... 4-27 Chapter II Internal Natural Dreams 28-62 Chapter III External Natural Dreams ................. 63-74 Chapter IV Supernatural Dreams ...................... 75-94 Chapter V Shakespeare’s Use of Dreams 95-111 Bibliography 112-115 INTRODUCTION This study deals specifically with dream theories that are recorded in English books published before 1616, the year of Shakespeare1s death, with a few notable exceptions such as Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Though this thesis does not pretend to include all available material on this subject during Shakespeare*s time, yet I have attempted to utilise all significant material found in the prose writings of selected doctors, theologians, translated Latin writers, recognised Shakespeare sources (Holinshed, Plutarch), and other prose writers of the time? in a few poets; and in representative dramatists. Though some sources were not originally written during the Elizabethan period, such as classical translations and early poetry, my criterion has been that, if the work was published in English and was thus currently available, it may be justifiably included in this study. Most of the source material is found in prose, since this A medium is more suited than are imaginative poetry anl drama y:/h to the expository discussions of dreams. The imaginative drama I speak of here includes Shakespeare, of course. -

Géraldine Crahay a Thesis Submitted in Fulfilments of the Requirements For

‘ON AURAIT PENSÉ QUE LA NATURE S’ÉTAIT TROMPÉE EN LEUR DONNANT LEURS SEXES’: MASCULINE MALAISE, GENDER INDETERMINACY AND SEXUAL AMBIGUITY IN JULY MONARCHY NARRATIVES Géraldine Crahay A thesis submitted in fulfilments of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in French Studies Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures June 2015 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix Declaration and Consent ........................................................................................................... xi Introduction: Masculine Ambiguities during the July Monarchy (1830‒48) ............................ 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework: Masculinities Studies and the ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity ............................. 4 Literature Overview: Masculinity in the Nineteenth Century ......................................................... 9 Differences between Masculinité and Virilité ............................................................................... 13 Masculinity during the July Monarchy ......................................................................................... 16 A Model of Masculinity: -

Sept. 15, 2019

September 15, 2019 24th Sunday in Ordinary Time Our parish still has no phone lines. I’ve talked to 10 people over at CenturyLink last week and nobody will listen to me. I’m not an expert. I just want a tech to come out and I can show him what’s going on. I was really upset Friday because I called and said, “You guys were supposed to be here by 5:00.” It was 5:15. “Oh, it says here it can be done remotely.” No, it cannot be done remotely, I need somebody here. “Well, you’ve got to wait until the work order’s finished at 6:00 tonight and call back to repair and service and talk to them.” So I did. They’re going to come out Monday, when I’m not here. Maybe this week we’ll have phone service, who knows. It’s interesting building buildings. Somebody was asking me the other day, “Isn’t it tremendously stressful? How can you do that and be spiritual too?” I said, “You don’t.” I’m going to read you a modern day prodigal son. Dear Dad, It is with heavy heart that I write this letter. I decided to elope with my new girlfriend tomorrow. We wanted to avoid a scene with you and Mom. I found real passion with Tamara, and she is so lovely even with her nose piercing, tattoos and her tight motorcycle clothes. It’s not only the joy Dad, she’s pregnant and Tamara said that we’ll be very happy. -

My Children, Teaching, and Nimrod the Word

XIV Passions: My Children, Teaching, and Nimrod The word passion has most often been associated with strong sexual desire or lust. I have felt a good deal of that kind of passion in my life but I prefer not to speak of it at this moment. Instead, it is the appetite for life in a broader sense that seems to have driven most of my actions. Moreover, the former craving is focused on an individual (unless the sexual drive is indiscriminant) and depends upon that individual for a response in order to intensify or even maintain. Fixating on my first husband—sticking to him no matter what his response, not being able to say goodbye to him —almost killed me. I had to shift the focus of my sexual passion to another and another and another in order to receive the spark that would rekindle and sustain me. That could have been dangerous; I was lucky. But with the urge to create, the intense passion to “make something,” there was always another outlet, another fulfillment just within reach. My children, teaching, and Nimrod, the journal I edited for so many years, eased my hunger, provided a way to participate and delight in something always changing and growing. from The passion to give birth to and grow with my children has, I believe, been expressed in previous chapters. I loved every aspect of having children conception, to the four births, three of which I watched in a carefully placed mirror at the foot of the hospital delivery room bed: May 6, 1957, birth of Leslie Ringold; November 8, 1959, birth of John Ringold; August 2, 1961: birth of Jim Ringold; July 27, 1964: birth of Suzanne Ringold (Harman). -

Summer 2021 M D I a P

Planning for Sustainability: Effective Wastewater Management Strategies for Communities, 10 Legislative Update, 8 Take a Chance on Me: Hiring Veterans, 14 Remembering Dick Otis, 16 4 2 7 . o N t i m r e P H N , r e t s e h c n a SUMMER 2021 M D I A P e g a t s o P . S . U D T S T R S R P 2 TM Passive Onsite Wastewater Treatment Systems ADVERTISER INDEX Combined Treatment and Dispersal Skimmer • Treats and disperses Tabs Ridges wastewater in the same footprint. • No electricity, replacement media or maintenance required. Geotextile • Flexible configurations for sloped or curved sites. Bio-Accelerator® Plastic Fiber Mat P E I presbyenvironmental.com • [email protected] • (800) 473-5298 Presby Environmental, Inc. An Infiltrator Water Technologies Company INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 A Note From The President ...................... 4 NOWRA Board of Directors ...................... 5 State Affiliate News .................................. 6 Legislative Update .................................... 8 Corporate Members ................................. 9 Feature: Planning for Sustainability ........ 10 Take a Chance on Me: Hiring Veterans ... 14 Tribute to Dick Otis ................................. 16 Executive Director’s Message ................. 20 Industry News ......................................... 22 Thank you to Eric Casey .......................... 23 ADVERTISER INDEX Presby Environmental ..........................................2 Jet, Inc. ..............................................................15 Salcor ...................................................................5 -

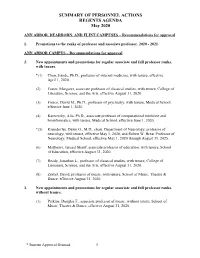

May 2020 Personnel Actions

SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR, DEARBORN, AND FLINT CAMPUSES – Recommendations for approval 1. Promotions to the ranks of professor and associate professor, 2020 - 2021. ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 2. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, with tenure. *(1) Chen, Jiande, Ph.D., professor of internal medicine, with tenure, effective April 1, 2020. (2) Foster, Margaret, associate professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (3) Fresco, David M., Ph.D., professor of psychiatry, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. (4) Karnovsky, Alla, Ph.D., associate professor of computational medicine and bioinformatics, with tenure, Medical School, effective June 1, 2020. *(5) Kleindorfer, Dawn O., M.D., chair, Department of Neurology, professor of neurology, with tenure, effective May 1, 2020, and Robert W. Brear Professor of Neurology, Medical School, effective May 1, 2020 through August 31, 2025. (6) Matthews, Jamaal Sharif, associate professor of education, with tenure, School of Education, effective August 31, 2020. (7) Ready, Jonathan L., professor of classical studies, with tenure, College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, effective August 31, 2020. (8) Zerkel, David, professor of music, with tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. 3. New appointments and promotions for regular associate and full professor ranks, without tenure. (1) Perkins, Douglas F., associate professor of music, without tenure, School of Music, Theatre & Dance, effective August 31, 2020. * Interim Approval Granted 1 SUMMARY OF PERSONNEL ACTIONS REGENTS AGENDA May 2020 ANN ARBOR CAMPUS – Recommendations for approval 4. -

Pretty Tgirls Magazine Is a Production of the Pretty Tgirls Group and Is Intended As a Free Resource for the Transgendered Community

PrettyPretty TGirlsTGirls MagazineMagazine Featuring An Interview with Melissa Honey December 2008 Issue Pretty TGirls Magazine is a production of the Pretty TGirls Group and is intended as a free resource for the Transgendered community. Articles and advertisements may be submitted for consideration to the editor, Rachel Williston, at [email protected] . It is our hope that our magazine will increase the understanding of the TG world and better acceptance of TGirls in our society. To that end, any articles are appreciated and welcomed for review ! Pretty TGirls Magazine – December 2008 page 1 PrettyPretty TGirlsTGirls MagazineMagazine December 2008 Welcome to the December 2008 issue … Take pride and joy with being a TGirl ! Table of contents: Our Miss 2008 Cover Girls ! Our Miss December 2008 Cover Girls Cover Girl Feature – Melissa Honey Editor’s Corner – Rachel Williston Ask Sarah – Sarah Cocktails With Nicole – Nicole Morgin Dear Abby L – Abby Lauren TG Crossword – Rachel Williston In The Company Of Others – Candice O. Minky TGirl Tips – Melissa Lynn Traveling As A TGirl – Mary Jane My “Non Traditional” Makeover – Barbara M. Davidson Transgender Tunes To Try – Melissa Lynn Then and Now Photo’s Recipes by Mollie – Mollie Bell Transmission: Identity vs. Identification – Nikki S. Candidly Transgender – Brianna Austin TG Conferences and Getaways Advertisements and newsy items Our 2008 Calendar! Magazine courtesy of the Pretty TGirls Group at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/prettytgirls Pretty TGirls Magazine – December 2008 page 2 Our Miss December 2008 Cover Girls ! How about joining us? We’re a tasteful, fun group of girls and we love new friends! Just go to … http://groups.yahoo.com/group/prettytgirls Pretty TGirls Magazine – December 2008 page 3 An Interview With Melissa Honey Question: When did you first start crossdressing? Melissa: Early teens, I found a pair of nylons and thought what the heck lets try them on! I was always interested in looking at women's legs and loved the look of nylons. -

The 35Th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy Award

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES 35th ANNUAL DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT EMMY ® AWARD NOMINATIONS Daytime Emmy Awards To Be Telecast June 20, 2008 On ABC at 8:00 p.m. (ET) Live from Hollywood’s’ Kodak Theatre Regis Philbin to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York – April 30, 2008 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences today announced the nominees for the 35th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy ® Awards. The announcement was made live on ABC’s “The View”, hosted by Whoopi Goldberg, Joy Behar, Elisabeth Hasselbeck, and Sherri Shepherd. The nominations were presented by “All My Children” stars Rebecca Budig (Greenlee Smythe) and Cameron Mathison (Ryan Lavery), Farah Fath (Gigi Morasco) and John-Paul Lavoisier (Rex Balsam) of “One Life to Live,” Marcy Rylan (Lizzie Spaulding) from “Guiding Light” and Van Hansis (Luke Snyder) of “As the World Turns” and Bryan Dattilo (Lucas Horton) and Alison Sweeney (Sami DiMera) from “Days of our Lives.” Nominations were announced in the following categories: Outstanding Drama Series; Outstanding Lead Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Supporting Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Younger Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Talk Show – Informative; Outstanding Talk Show - Entertainment; and Outstanding Talk Show Host. As previously announced, this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award will be presented to Regis Philbin, host of “Live with Regis and Kelly.” Since Philbin first stepped in front of the camera more than 40 years ago, he has ambitiously tackled talk shows, game shows and almost anything else television could offer. Early on, Philbin took “A.M. Los Angeles” from the bottom of the ratings to number one through his 7 year tenure and was nationally known as Joey Bishop’s sidekick on “The Joey Bishop Show.” In 1983, he created “The Morning Show” for WABC in his native Manhattan. -

Israël Veut Un « Changement Complet » De La Politique Menée Par L'olp

LeMonde Job: WMQ0208--0001-0 WAS LMQ0208-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 01-08-97 T.: 11:23 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:01,11, Base : LMQPAG 27Fap:99 No:0328 Lcp: 196 CMYK CINQUANTE-TROISIÈME ANNÉE – No 16333 – 7,50 F SAMEDI 2 AOÛT 1997 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Les athlètes Israël veut un « changement complet » à Athènes de la politique menée par l’OLP Rigor Mortis a Brigitte Aubert Participation record Benyamin Nétanyahou exige de Yasser Arafat qu’il éradique le terrorisme a aux championnats ISRAÉLIENS et responsables de Jérusalem. Les premiers accusent Le premier ministre a mis Yasser maine. « On ne peut faire avancer du monde l’Autorité palestinienne se sont l’OLP de ne pas en faire assez dans Arafat en demeure d’éradiquer le le processus diplomatique alors que renvoyés, jeudi 31 juillet, la res- la lutte contre le terrorisme ; les terrorisme et a juré qu’il n’y aurait l’Autorité palestinienne ne prend une nouvelle inédite ponsabilité de l’attentat qui, la seconds affirment que la politique pas de reprise des conversations pas les mesures minimales qu’elle qui s’ouvrent samedi veille, a fait quinze morts et plus du gouvernement de Benyamin israélo-palestiniennes tant qu’Is- s’est engagée à prendre contre les de cent cinquante blessés sur un Nétanyahou favorise la montée raël ne jugerait pas l’action de foyers du terrorisme », a dit M. Né- dames a des marchés les plus populaires de des extrémistes palestiniens. l’OLP satisfaisante dans ce do- tanyahou. « Il faut un changement du noir La pollution peut complet de politique de la part des Palestiniens, une campagne vigou- perturber les épreuves reuse, systématique et immédiate pour éliminer le terrorisme », a-t-il Les Dames a lancé, jeudi soir, à la télévision. -

Sample Chapter

3 Pain, Misery, Hate and Love All at Once A THEOLOGY OF SUFFERING I remember the period well. It was the months following the 1992 LA Riots. We were young, full of energy, and having bore witness to the destructive forces that tore our community apart, we wanted to change the direction of the ‘hood. So what did we do? We organized gangs, nonprofits and people with like-minded worldviews to create something that had never been done, a gang truce. A fifteen-city organizational effort involving gang leaders, commu- nity organizations and rappers like Tupac, the then lesser known Snoop Dogg and former members of NWA, as well as people who wanted to see a change from the violence of the 1980s, put together posters, banners, flyers and events that helped put a message of peace out in the commu- nity. Large gangs like the Crips and the Bloods came to park BBQ’s to celebrate the newfound peace. MTV covered many of the events. For the first time it seemed as though urban peace was beginning to take shape. I was truly amazed. Especially being as angry as I was after the Rodney King trial verdict, I was beginning to see some change that I could be a part of. We decided that each city needed to take their concerns to City SoulOfHipHop.indb 75 4/26/10 11:13:30 AM 76 THE SOUL OF HIP HOP Hall. We had hoped to file for a “state of emergency” to begin receiv- ing federal funds to clean up our ‘hoods and begin to restore our fam- ilies. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu .................................................................................................