Coccidioidomycosis STUDY GROUP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Athlete's Foot

South African Family Practice 2018; 60(5):37-41 S Afr Fam Pract Open Access article distributed under the terms of the ISSN 2078-6190 EISSN 2078-6204 Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] © 2018 The Author(s) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 REVIEW Managing athlete’s foot Nkatoko Freddy Makola,1 Nicholus Malesela Magongwa,1 Boikgantsho Matsaung,1 Gustav Schellack,2 Natalie Schellack3 1 Academic interns, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 2 Clinical research professional, pharmaceutical industry 3 Professor, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed at providing a succinct overview of the condition tinea pedis, commonly referred to as athlete’s foot. Tinea pedis is a very common fungal infection that affects a significantly large number of people globally. The presentation of tinea pedis can vary based on the different clinical forms of the condition. The symptoms of tinea pedis may range from asymptomatic, to mild- to-severe forms of pain, itchiness, difficulty walking and other debilitating symptoms. There is a range of precautionary measures available to prevent infection, and both oral and topical drugs can be used for treating tinea pedis. This article briefly highlights what athlete’s foot is, the different causes and how they present, the prevalence of the condition, the variety of diagnostic methods available, and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the -

HIV Infection and AIDS

G Maartens 12 HIV infection and AIDS Clinical examination in HIV disease 306 Prevention of opportunistic infections 323 Epidemiology 308 Preventing exposure 323 Global and regional epidemics 308 Chemoprophylaxis 323 Modes of transmission 308 Immunisation 324 Virology and immunology 309 Antiretroviral therapy 324 ART complications 325 Diagnosis and investigations 310 ART in special situations 326 Diagnosing HIV infection 310 Prevention of HIV 327 Viral load and CD4 counts 311 Clinical manifestations of HIV 311 Presenting problems in HIV infection 312 Lymphadenopathy 313 Weight loss 313 Fever 313 Mucocutaneous disease 314 Gastrointestinal disease 316 Hepatobiliary disease 317 Respiratory disease 318 Nervous system and eye disease 319 Rheumatological disease 321 Haematological abnormalities 322 Renal disease 322 Cardiac disease 322 HIV-related cancers 322 306 • HIV INFECTION AND AIDS Clinical examination in HIV disease 2 Oropharynx 34Neck Eyes Mucous membranes Lymph node enlargement Retina Tuberculosis Toxoplasmosis Lymphoma HIV retinopathy Kaposi’s sarcoma Progressive outer retinal Persistent generalised necrosis lymphadenopathy Parotidomegaly Oropharyngeal candidiasis Cytomegalovirus retinitis Cervical lymphadenopathy 3 Oral hairy leucoplakia 5 Central nervous system Herpes simplex Higher mental function Aphthous ulcers 4 HIV dementia Kaposi’s sarcoma Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy Teeth Focal signs 5 Toxoplasmosis Primary CNS lymphoma Neck stiffness Cryptococcal meningitis 2 Tuberculous meningitis Pneumococcal meningitis 6 -

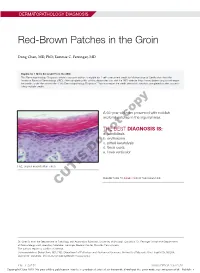

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

Tinea Capitis 2014 L.C

BJD GUIDELINES British Journal of Dermatology British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of tinea capitis 2014 L.C. Fuller,1 R.C. Barton,2 M.F. Mohd Mustapa,3 L.E. Proudfoot,4 S.P. Punjabi5 and E.M. Higgins6 1Department of Dermatology, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, U.K. 2Department of Microbiology, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds LS1 3EX, U.K. 3British Association of Dermatologists, Willan House, 4 Fitzroy Square, London W1T 5HQ, U.K. 4St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, St Thomas’ Hospital, Westminster Bridge Road, London SE1 7EH, U.K. 5Department of Dermatology, Hammersmith Hospital, 150 Du Cane Road, London W12 0HS, U.K. 6Department of Dermatology, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, U.K. 1.0 Purpose and scope Correspondence Claire Fuller. The overall objective of this guideline is to provide up-to- E-mail: [email protected] date, evidence-based recommendations for the management of tinea capitis. This document aims to update and expand Accepted for publication on the previous guidelines by (i) offering an appraisal of 8 June 2014 all relevant literature since January 1999, focusing on any key developments; (ii) addressing important, practical clini- Funding sources cal questions relating to the primary guideline objective, i.e. None. accurate diagnosis and identification of cases; suitable treat- ment to minimize duration of disease, discomfort and scar- Conflicts of interest ring; and limiting spread among other members of the L.C.F. has received sponsorship to attend conferences from Almirall, Janssen and LEO Pharma (nonspecific); has acted as a consultant for Alliance Pharma (nonspe- community; (iii) providing guideline recommendations and, cific); and has legal representation for L’Oreal U.K. -

List Item Posaconazole SP-H-C-611-II

European Medicines Agency London, 4 December 2006 Product Name: POSACONAZOLE SP Procedure number: EMEA/H/C/611/II/01 authorised SCIENTIFIC DISCUSSION longer no product Medicinal 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) 74 18 86 68 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.europa.eu 1 Introduction Fungal infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Filamentous mould and yeast-like fungi are ubiquitous organisms found worldwide in many different media. The Candida species are the most common cause of fungal infections. However, epidemiologic shifts have begun to occur, most likely due to the prophylactic and empiric use of antifungal agents. Emerging fungal pathogens, such as Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Zygomycetes, are changing the clinical spectrum of fungal diagnoses. Pathogens General risk factors for invasive fungal infections are exposure to pathogens, an impaired immune system, and fungal spores. The presence of a colonised environment, partnered with a disruption in a physiologic barrier, potentiates the risk of an invasive fungal infection in an immunologically impaired host, such as a patient infected with HIV, someone taking chronic systemic steroids, or a transplant recipient. In addition, contaminated implanted devices (e.g., catheters, prostheses), external devices (e.g., contact lenses), and community reservoirs (e.g., hand lotion, pepper shakers) have all been implicated as sources of fungal outbreaks. Candida albicans continues to be the most frequent cause of invasive fungal infections in most patient populations. However, prophylaxis and the widespread use of antifungal agents as empiric therapy for neutropenic fever have led to a shift in the epidemiology of invasive Candida infections. -

Fungal Diseases

Abigail Zuger Fungal Diseases For creatures your size I offer a free choice of habitat, so settle yourselves in the zone that suits you best, in the pools of my pores or the tropical forests of arm-pit and crotch, in the deserts of my fore-arms, or the cool woods of my scalp Build colonies: I will supply adequate warmth and moisture, the sebum and lipids you need, on condition you never do me annoy with your presence, but behave as good guests should not rioting into acne or athlete's-foot or a boil. from "A New Year Greeting" by W.H. Auden. Introduction Most of the important contacts between human beings and the fungi occur outside medicine. Fungi give us beer, bread, antibiotics, mushroom omelets, mildew, and some devastating crop diseases; their ability to cause human disease is relatively small. Of approximately 100,000 known species of fungi, only a few hundred are human pathogens. Of these, only a handful are significant enough to be included in medical texts and introductory courses like this one. On the other hand, while fungal virulence for human beings is uncommon, the fungi are not casual pathogens. In the spectrum of infectious diseases, they can cause some of the most devastating and stubborn infections we see. Most human beings have a strong natural immunity to the fungi, but when this immunity is breached the consequences can be dramatic and severe. As modern medicine becomes increasingly adept in prolonging the survival of some patients with naturally-occurring immunocompromise (diabetes, cancer, AIDS), and causing iatrogenic immunocompromise in others (antibiotics, cytotoxic and MID 25 & 26 immunomodulating drugs), fungal infections are becoming increasingly important. -

Valley Fever a K a Coccidioidomycosis Coccidioidosis Coccidiodal Granuloma San Joaquin Valley Fever Desert Rheumatism Valley Bumps Cocci Cox C

2019 Lung Infection Symposium - Libke 10/26/2019 58 YO ♂ • 1974 PRESENTED WITH HEADACHE – DX = COCCI MENINGITIS WITH HYDROCEPHALUS – Rx = IV AMPHOTERICIN X 6 WKS – VP SHUNT – INTRACISTERNAL AMPHO B X 2.5 YRS (>200 PUNCTURES) • 1978 – 2011 VP SHUNT REVISIONS X 5 • 1974 – 2019 GAINFULLY EMPLOYED, RAISED FAMILY, RETIRED AND CALLS OCCASIONALLY TO SEE HOW I’M DOING. VALLEY FEVER A K A COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS COCCIDIOIDOSIS COCCIDIODAL GRANULOMA SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY FEVER DESERT RHEUMATISM VALLEY BUMPS COCCI COX C 1 2019 Lung Infection Symposium - Libke 10/26/2019 COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS • DISEASE FIRST DESCRIBED IN 1892 – POSADAS –ARGENTINA – RIXFORD & GILCHRIST - CALIFORNIA – INITIALLY THOUGHT PARASITE – RESEMBLED COCCIDIA “COCCIDIOIDES” – “IMMITIS” = NOT MINOR COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS • 1900 ORGANISM IDENTIFIED AS FUNGUS – OPHULS AND MOFFITT – ORGANISM CULTURED FROM TISSUES OF PATIENT – LIFE CYCLE DEFINED – FULFULLED KOCH’S POSTULATES 2 2019 Lung Infection Symposium - Libke 10/26/2019 COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS • 1932 ORGANISM IN SOIL SAMPLE FROM DELANO – UNDER BUNKHOUSE OF 4 PATIENTS – DISEASE FATAL • 1937 DICKSON & GIFFORD CONNECTED “VALLEY FEVER” TO C. IMMITIS – USUALLY SELF LIMITED – FREQUENTLY SEEN IN SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY – RESPIRATORY TRACT THE PORTAL OF ENTRY The usual cause for coccidioidomycosis in Arizona is C. immitis A. True B. False 3 2019 Lung Infection Symposium - Libke 10/26/2019 COCCIDIOIDAL SPECIES • COCCIDIOIDES IMMITIS – CALIFORNIA • COCCIDIOIDES POSADASII – NON-CALIFORNIA • ARIZONA, MEXICO • OVERLAP IN SAN DIEGO AREA THE MICROBIAL WORLD • PRIONS -

Detection of Histoplasma DNA from Tissue Blocks by a Specific

Journal of Fungi Article Detection of Histoplasma DNA from Tissue Blocks by a Specific and a Broad-Range Real-Time PCR: Tools to Elucidate the Epidemiology of Histoplasmosis Dunja Wilmes 1,*, Ilka McCormick-Smith 1, Charlotte Lempp 2 , Ursula Mayer 2 , Arik Bernard Schulze 3 , Dirk Theegarten 4, Sylvia Hartmann 5 and Volker Rickerts 1 1 Reference Laboratory for Cryptococcosis and Uncommon Invasive Fungal Infections, Division for Mycotic and Parasitic Agents and Mycobacteria, Robert Koch Institute, 13353 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (I.M.-S.); [email protected] (V.R.) 2 Vet Med Labor GmbH, Division of IDEXX Laboratories, 71636 Ludwigsburg, Germany; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (U.M.) 3 Department of Medicine A, Hematology, Oncology and Pulmonary Medicine, University Hospital Muenster, 48149 Muenster, Germany; [email protected] 4 Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, 45147 Essen, Germany; [email protected] 5 Senckenberg Institute for Pathology, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt, 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-30-187-542-862 Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Lack of sensitive diagnostic tests impairs the understanding of the epidemiology of histoplasmosis, a disease whose burden is estimated to be largely underrated. Broad-range PCRs have been applied to identify fungal agents from pathology blocks, but sensitivity is variable. In this study, we compared the results of a specific Histoplasma qPCR (H. qPCR) with the results of a broad-range qPCR (28S qPCR) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens from patients with proven fungal infections (n = 67), histologically suggestive of histoplasmosis (n = 36) and other mycoses (n = 31). -

Therapies for Common Cutaneous Fungal Infections

MedicineToday 2014; 15(6): 35-47 PEER REVIEWED FEATURE 2 CPD POINTS Therapies for common cutaneous fungal infections KENG-EE THAI MB BS(Hons), BMedSci(Hons), FACD Key points A practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of common fungal • Fungal infection should infections of the skin and hair is provided. Topical antifungal therapies always be in the differential are effective and usually used as first-line therapy, with oral antifungals diagnosis of any scaly rash. being saved for recalcitrant infections. Treatment should be for several • Topical antifungal agents are typically adequate treatment weeks at least. for simple tinea. • Oral antifungal therapy may inea and yeast infections are among the dermatophytoses (tinea) and yeast infections be required for extensive most common diagnoses found in general and their differential diagnoses and treatments disease, fungal folliculitis and practice and dermatology. Although are then discussed (Table). tinea involving the face, hair- antifungal therapies are effective in these bearing areas, palms and T infections, an accurate diagnosis is required to ANTIFUNGAL THERAPIES soles. avoid misuse of these or other topical agents. Topical antifungal preparations are the most • Tinea should be suspected if Furthermore, subsequent active prevention is commonly prescribed agents for dermatomy- there is unilateral hand just as important as the initial treatment of the coses, with systemic agents being used for dermatitis and rash on both fungal infection. complex, widespread tinea or when topical agents feet – ‘one hand and two feet’ This article provides a practical approach fail for tinea or yeast infections. The pharmacol- involvement. to antifungal therapy for common fungal infec- ogy of the systemic agents is discussed first here. -

Yeast Infection Division of Disease Control What Do I Need to Know?

Division of Disease Control What Do I Need To Know? Yeast Infection (Thrush, Diaper Rash, Vaginitis) What is a yeast infection? Yeast infections are caused by a fungus called Candida albicans. These infections can present in a variety of forms. Yeast infections in women can infect the vagina, called vaginitis. Thrush causes mouth infections in young infants and can also be a presenting sign of HIV infection in adults. Candida also may be the cause of many types of diaper rash in young children. Who is at risk for a yeast infection? Anyone can get a yeast infection. What are the symptoms of a yeast infection? Candidia diaper rash: The diaper area is red. The redness is worse in the creases. Redness is often bordered by red pimples. Rash may have a shiny appearance. Sores or cracking or oozing is present in severe cases. Thrush White patches appear on the inside of cheeks and gums and tongue. Thrush usually causes no other signs or symptoms. Vaginitis Vaginal irritation, intense itchiness and vaginal discharge. How soon do symptoms appear? Incubation period is unknown. How is a yeast infection spread? The fungus is present in the intestinal tract and mucous membranes of healthy people. A warm environment allows for growth and spread. Page 1 of 2 Last Updated: 01/2016 Person-to-person transmission may occur from a woman to her infant when the mother has a yeast infection in her vagina and in breastfeeding mothers whose babies with thrush infect the mothers’ nipples. When and for how long is a person able to spread the disease? A person can spread disease as long as the infection is present. -

Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Tutorial for Primary Care Professionals, Now in Its Second Printing

Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis) Tutorial for Primary Care Professionals Prepared by the VALLEY FEVER CENTER FOR EXCELLENCE The University of Arizona 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................... 4 SECTION 1 ................................................................................. 7 OVERVIEW OF COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS History .................................................................................... 8 Mycology ................................................................................ 8 Epidemiology ....................................................................... 10 Spectrum of disease ........................................................... 11 Current therapies ................................................................. 12 SECTION 2 ............................................................................... 13 THE IMPORTANCE OF VALLEY FEVER IN PRIMARY CARE Case reporting ..................................................................... 14 Value of early diagnosis ....................................................... 17 SECTION 3 ............................................................................... 19 PRIMARY CARE MANAGEMENT OF COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS C onsider the diagnosis ........................................................ 20 O rder the right tests ............................................................. 23 C heck for risk factors .......................................................... 29 C heck for complications -

Yeast Infection (Candidiasis)

PROVIDER YEAST INFECTION (CANDIDIASIS) Candida can normally be found on the skin and in the mouth, throat, intestinal tract, and vagina of healthy people. In children, yeast infections are commonly found in the mouth or throat (thrush) or the diaper area. CAUSE Candida albicans, a fungus. SYMPTOMS Thrush - White, slightly raised patches on the tongue or inside the cheek. Diaper Rash - Smooth, shiny "fire engine" red rash with a raised border. Children who suck their thumbs or fingers may occasionally develop Candida infections around their fingernails. Under certain conditions, such as during antibiotic use or when skin is damaged and exposed to excessive moisture, the balance of the normal, healthy skin germs is upset. Therefore, yeast that normally live on the skin can overgrow and cause yeast infections. Most of the time these infections heal quickly, but sometimes illness can occur in infants, persons with weakened immune systems, or those taking certain antibiotics. SPREAD Rarely, by contact with skin lesions and mouth secretions of infected persons or asymptomatic carriers. Most infants who have Candida got it from their mother during childbirth. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, outbreaks of thrush in childcare settings may be the result of increased use of antibiotics rather than newly acquired Candida infections. INCUBATION Variable. For thrush in infants, it usually takes 2 to 5 days. For others, yeast infections may occur while taking antibiotics or shortly after stopping the antibiotics. CONTAGIOUS Contagious while lesions are present. Most infections occur from yeast in the PERIOD person’s own body. DIAGNOSIS Recommend parents/guardians call their healthcare provider to identify the fungus.