An Ethnohistory of the Temple Trust of Manakamana in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Manaslu Trekking - 10 Days

Lower Manaslu Trekking - 10 Days Trip Facts Destination Nepal Duration 10 Days Group Size 2 - 40 Trip Code DWT21 Grade Moderate Activity Manaslu Treks Region Manaslu Region Max. Altitude 5,160m at Larkya la pass Nature of Trek N/A Activity per Day Approx. 4-6 hrs walking Accomodation Selected hotel in Kathmandu and homestay during the trek Start / End Point Kathmandu / Kathmandu Meals Included Breakfast in Kathmandu and all meals during the trek Best Season Feb, Mar, Apri, May, June, Sep, Oct, Nov & Dec, Transportation Private vehicle A Leading Himalayan Trekking & Adventure Specialists TRULY YOUR TRUSTED NEPAL’S TRIP OPERATOR. Discovery world Trekking would like to recommend all our trekkers that they should add an extra day at Kathmandu at weekdays (Not in the weekend) before we start our Lower Manaslu Trekking next day after for Manaslu special permit process where we need your original Passport with Nepali visa at Immigrant Office Nepal and also for official Briefing as proper mental guidance and necessary information just to have a recheck of equipment and goods for the journey to make sure you haven't forgotten anything and if forgotten, then make sure that you are provided with those things ASAP on that very day at our office. On our way, we'll be travelling in public buses but if you want a bit comfortable ride as the road is not that good we can provide you jeep at some extra cost as simple cars can't go there. About the Trip Best Price Guarantee Hassle-Free Booking No Booking or Credit Card Fees Team of highly experienced Experts Your Happiness Guaranteed Highlights Explore historical Gorkha Palace, home of the king Prithvi Narayan Shah, Gorkha meusem, Gorakkhali temple. -

Nepal Itenary

Phewa Lake WONDERS OF NEPAL 06 Nights / 07 Days 2N Kathmandu - 1N Pokhra - 2N Chitwan - 1N Kathmandu PACKAGE HIGHLIGHTS • Visit Kathmandu, Pashupatinath, Boudhanath, Durbar Square & Swayambhunath Stupa • Cable car ride to Manakamana temple & Boating in Phewa Lake • Popular Lakes of Pokhra - Phewa, Begnas and Rupa • Sightseeing in Pokhra • Chitwan National Park and Elephant Safari • Services of English speaking guide during sightseeing tours • Assistance at airport and sightseeing tours by private air-conditioned vehicle • Start and End in Kathmandu Manakamana Temple Day 01 Arrival in Kathmandu Our representative will meet you upon arrival in Kathmandu - an exotic and fascinating showcase of a very rich culture, art and tradition. The valley, roughly an oval bowl, is encircled by a range of green terraced hills and dotted by compact clusters of red tiled-roofed houses. After reaching, check-in at the hotel and spend the rest of the evening at leisure with an overnight stay in Kathmandu. Day 02 Sightseeing in Kathmandu After breakfast, set out to discover the bustling Kathmandu. Start by visiting Pashupatinath temple, Boudhanath temple and famous Durbar Square. Also visit Swayambhunath Stupa, the most ancient and enigmatic of all the holy shrines in Kathmandu valley. In the evening, visit the Thamel neighborhood & the Garden of Dreams. Stay overnight in Kathmandu. Day 03 Kathmandu – Pokhara (210 kms / approx.5 hours) After breakfast, drive to Pokhara and en route enjoy a beautiful cable car ride to Manakamana temple. Pokhara is known for its lovely lakes - Phewa, Begnas and Rupa, which have their source in the glacial Annapurna Range of the Himalayas. -

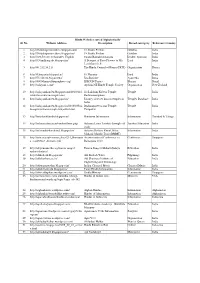

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Le Népal : Deux Mois Après Le Séisme Du 25 Avril 2015

Groupe interparlementaire d’amitié France-Népal (1) Le Népal : deux mois après le séisme du 25 avril 2015 Actes du colloque du 23 juin 2015 Palais du Luxembourg Salle Clemenceau Les propos des intervenants durant cette journée d’échanges n’engagent qu’eux-mêmes, et ne sauraient donc être imputés au Sénat, ni considérés comme exprimant son point de vue ou comme ayant son approbation. 1 ( ) Membres du groupe interparlementaire d’amitié France-Népal : M. Yvon COLLIN, Président ; Mme Leila AÏCHI, Secrétaire ; M. Michel BERSON ; Mme Joëlle GARRIAUD-MAYLAM ; Mme Sylvie GOY-CHAVENT, Secrétaire ; Mme Christiane KAMMERMANN, Vice-Présidente ; Mme Françoise LABORDE ; M. Jacques MÉZARD ; Mme Marie-Françoise PEROL-DUMONT, Vice-Présidente ; M. Simon SUTOUR. ________________ N° GA 131 - Janvier 2016 - 3 - SOMMAIRE Pages AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................................................................. 9 M. Yvon COLLIN, Président du groupe d’amitié France – Népal ..................................... 9 PARTIE I - LE NÉPAL ÉBRANLÉ : CONSÉQUENCES HUMAINES ET POLITIQUES DU SÉISME DU 25 AVRIL 2015 ................................................................11 Mme Marie LECOMTE-TILOUINE, Directrice de recherche au Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), attachée au laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale (CNRS/Collège de France/ EHESS) ................................................................................11 I. L’HISTOIRE DU NÉPAL S’EFFONDRE ....................................................................... -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Earthquake Emergency Preparedness and Response – a Case Study of Thecho Vdc Lalitpur

EARTHQUAKE EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE – A CASE STUDY OF THECHO VDC LALITPUR A Thesis Submitted to the Central Department of Geography Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of Tribhuvan University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for MASTER’S DEGREE In GEOGRAPHY By SONY MAHARJAN Symbol No. 280166 Central Department of Geography Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu January 2016 LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION This is to certify that the thesis submitted by Miss Sony Maharjan, “ Earthquake Emergency Preparedness and Response - A Case Study of Thecho VDC.”, has been prepared under my supervision in partial fulfillment of requirement for the Degree of Master of Social Science in Geography. I recommend this thesis to the evaluation committee for examination. Date: ………………………… Mrs. Shova Shrestha (Ph.D) Thesis Supervisor Associate Professor Central Department of Geography Tribhuvan University i Tribhuvan University Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences CENTRAL DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRPAY APPROVAL LETTER The present thesis submitted by Ms. Sony Maharjan entitled as “Earthquake Emergency Preparedness and Response - A Case Study of Thecho VDC” has been accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Master’s Degree of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science in Geography. Thesis Committee Mrs. Shova Shrestha (Ph.D) Thesis Supervisor Prof. Krishan Prashad Poude (Ph.D) External Examiner Prof. Padma Chandra Poudel (Ph.D) Head of the Department Date: ............................. ii ABSTRACT Natural disaster cannot be stopped but its effect can be minimized or avoided by science, technology and necessary human adjustment i.e. emergency preparedness. Earthquake is one natural event which gives severe threat due to the irregular time intervals between events and lack of adequate forecasting due to its extreme speed of onset. -

Tourism in Gorkha: a Proposition to Revive Tourism After Devastating Earthquakes

Tourism in Gorkha: A proposition to Revive Tourism After Devastating Earthquakes Him Lal Ghimire* Abstract Gorkha, the epicenter of devastating earthquake 2015 is one of the important tourist destinations of Nepal. Tourism is vulnerable sector that has been experiencing major crises from disasters. Nepal is one of the world’s 20 most disaster-prone countries where earthquakes are unique challenges for tourism. Nepal has to be very optimistic about the future of tourism as it has huge potentials to be the top class tourist destinations by implementing best practices and services. Gorkha tourism requires a strategy that will help manage crises and rapid recovery from the damages and losses. This paper attempts to explain tourism potentials of Gorkha, analyze the impacts of devastating earthquakes on tourism and outline guidelines to revive tourism in Gorkha. Key words: Disasters. challenges, strategies, planning, mitigation, positive return. Background Gorkha is one of the important tourist destinations in Nepal. Despite its natural beauty, historical and religious importance, diverse culture, very close from the capital city Kathmandu and other important touristic destinations Pokhara and Chitwan, tourism in Gorkha could not have been developed expressively. Gorkha was the epicenter of 7.8 earthquake on April 25, 2015 in Nepal that damaged or destroyed the tourism products and tourism activities were largely affected. Tourism is an expanding worldwide phenomenon, and has been observed that by the next century, tourism will be the single largest industry in the world. Today, tourism is also the subject of great media attention (Ghimire, 2014:98). Tourism industry, arguably one of the most important sources of income and foreign exchange, is growing rapidly. -

729 24 - 30 October 2014 20 Pages Rs 50

#729 24 - 30 October 2014 20 pages Rs 50 BIKRAM RAI Celebrating colours POST-MORTEM WHERE OF A TRAGEDY TO BE A We know that our preparedness GURKHA? was disastrous, the question is A retired Nepali how do we reduce the chances soldier who served of needless casualties in future in Singapore tells blizzards, fl oods or earthquakes? authors of a new EDITORIAL book: PAGE 2 “I love Singapore. ust like the Tihar palette (top), the country’s top leaders are trying to I am ready to go Jfind a way to craft a new constitution that will embrace all identities back and die for without undermining national unity. Senior leaders of the three main Singapore.” parties meeting at Gokarna Resort (above) over the holidays have so far EYE-WITNESS TO failed to come up with a compromise between single-identity based PAGE 16-17 federalism and the territorial model. But if the ruling NC-UML coalition SEARCH AND RESCUE agrees to increase the proportional representation ratio in future elections IN MUSTANG to make them more inclusive, it could convince the Maoist-Madhesi BY SUBINA SHRESTHA opposition about the rationale for fewer federal units based on geography. PAGE 3 CHONG ZI LIANG 2 EDITORIAL 24 - 30 OCTOBER 2014 #729 POST-MORTEM OF A TRAGEDY s with the other disasters in Nepal this year (Bhote Kosi landslide, Surkhet-Dang flashfloods and the We know that our preparedness was AEverest avalanche) there has been a lot of blame- disastrous, the question is how do throwing after the Annapurna blizzard last week that claimed at least 45 lives. -

Chemjong Cornellgrad 0058F

“LIMBUWAN IS OUR HOME-LAND, NEPAL IS OUR COUNTRY”: HISTORY, TERRITORY, AND IDENTITY IN LIMBUWAN’S MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dambar Dhoj Chemjong December 2017 © 2017 Dambar Dhoj Chemjong “LIMBUWAN IS OUR HOME, NEPAL IS OUR COUNTRY”: HISTORY, TERRITORY, AND IDENTITY IN LIMBUWAN’S MOVEMENT Dambar Dhoj Chemjong, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This dissertation investigates identity politics in Nepal and collective identities by studying the ancestral history, territory, and place-naming of Limbus in east Nepal. This dissertation juxtaposes political movements waged by Limbu indigenous people with the Nepali state makers, especially aryan Hindu ruling caste groups. This study examines the indigenous people’s history, particularly the history of war against conquerors, as a resource for political movements today, thereby illustrating the link between ancestral pasts and present day political relationships. Ethnographically, this dissertation highlights the resurrection of ancestral war heroes and invokes war scenes from the past as sources of inspiration for people living today, thereby demonstrating that people make their own history under given circumstances. On the basis of ethnographic examples that speak about the Limbus’ imagination and political movements vis-à-vis the Limbuwan’s history, it is argued in this dissertation that there can not be a singular history of Nepal. Rather there are multiple histories in Nepal, given that the people themselves are producers of their own history. Based on ethnographic data, this dissertation also aims to debunk the received understanding across Nepal that the history of Nepal was built by Kings. -

Trekking Trails in Nepal

Trek, Bike and Raft EXPLORING THE TOURISM POSSIBILITIES OF DOLPA THE RUBY VALLey TREK GANESH HIMAL REGION DiscoveringTAAN Tourism Destinations & Trekking Trails in Nepal LOWER MANASLU ECO TREK- GORKHA LUMBA - SUMBA PASS KANCHENJUNGA & MAKALU www.taan.org.np DiscoveringTAAN Tourism Destinations & Trekking Trails in Nepal © All rights reserved: Trekking Agencies' Association of Nepal- TAAN- 2012 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under Copyright Laws of the Nepal, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the TAAN. Any enquiries should be directed to TAAN, [email protected] Trekking Agencies' Association of Nepal (TAAN) P.O. Box : 3612 Maligaun Ganeshthan, Kathmandu Tel. : 977-1-4427473, 4440920, 4440921 Fax : 977-1-4419245 Email : [email protected] Price: Organizational NRs. 500, Individual NRs. 300. Publication Coordinator: Amber Tamang Designed Processed by: PrintComm 42244148, Kathmandu Printed in Nepal Discovering Tourism Destinations & Trekking Trails in Nepal 5 TAAN STRENGTHENING THE TREKKING TOURISM INDUSTRY am highly privileged to offer you this I book, which is a product of very hard work and dedication of the team of TAAN. This book, “TAAN- Discovering Tourism Destinations and Trekking Trails in Nepal”, is a very important book in the tourism industry of Nepal. There are dozens of trekking trails discovered and described in detail with day-to –day itineraries. Lumba-Sumba Pass Taplejung, Eco-cultural trails in Gorkha, high altitude treks and cultural book possible in time working days treks in Dhading Ganesh Himal region, and nights. and incredible, hidden treasures trekking in Dolpa district have been I remember all the individuals involved studied by different teams of experts in this process. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

A Light in the Heart: Faces of Nepal Celebrating 75 Years of the United Nations FOREWORD

eart: d Nations the H rs of the Unite yea ating 75 Faces of Nepal ebr l Ce A Light in A Light in the Heart: Faces of Nepal Celebrating 75 years of the United Nations Copyright ©2020 United Nations Development Programme Nepal All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Printed in Nepal First Printing, October 2020 A Light in the Heart: Faces of Nepal Celebrating 75 years of the United Nations FOREWORD 2020 has been a year of exceptional disruption for the world, This is for the above reason, -to uphold intergenerational compounded by an unprecedented global health crisis and its solidarity- that the book also presents several poems by accompanying economic and social impacts. Besides, in 2020, some Nepal’s greatest and most famous literary figures, such UNDP joined the United Nations team in Nepal to observe as Laxmi Prasad Devkota (Mahakavi) and Madhav Prasad three important events – the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Ghimire, with heartfelt tributes to them. To complement, there United Nations, the thirtieth anniversary of the International are beautiful poems by young poets, who are already part way Day for Older Persons, and the Decade of Healthy Ageing. through their respective literary journeys. In this way, the book embraces expressions from three Nepali generations. Thus, as an acknowledgement of a generation, UNDP organized a virtual exhibition of photographs of seventy-five And so I express sincere gratitude to those featured on the people born with the United Nations, who are featured in this photography – and through them to their whole generation –, book.