Prayers in Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuneo Come Porta Transfrontaliera Verso La Francia Meridionale”

Le relazioni tra il Piemonte e la Francia sono sempre stata strettissime. Oggi però si sta aprendo una fase nuova, di vera e propria integrazione del modello di sviluppo. -),!./ Questo studio di fattibilità, commissionato dal Comune di Cuneo, nell’ambito del Programma innovativo S.I.S.Te.M.A. Centro Nord, fi nanziato dal Ministero delle Infrastrutture e in ./6!2! coerenza con il Piano Strategico Cuneo 2020, analizza le opportunità e i rischi collegati alle 4/2)./ sfi de dell’integrazione. Il raddoppio del traforo al Col di Tenda, in particolare, risulta essere un fattore decisivo, se Cuneo come porta transfrontaliera :! accompagnato da misure adeguate, affi nché Cuneo come porta transfrontaliera Cuneo e il suo territorio possano orientare il verso la Francia meridionale verso la Francia meridionale proprio sviluppo in una logica di innovazione STUDIO DI FATTIBILITA e sostenibilità. Il Ministero delle Infrastrutture, con il !34) coordinamento dell’Arch. Gaetano Fontana, capo dipartimento per il coordinamento dello sviluppo del territorio, il personale e i servizi '%./6!' generali, ha lanciato da anni modalità innovative della gestione delle complessità territoriali. #5.%/ In particolare S.I.S.Te.M.A. (Sviluppo integrato 3!6/.!/.!! Sistemi Territoriali Multi Azioni), coordinato dal responsabile unico del procedimento Arch. Francesco Giacobone, sta coinvolgendo una serie di territori-bersaglio nei quali si articola il Documento attuativo del sistema infrastrutturale e territoriale italiano. Programma Innovativo Il Comune di Cuneo, impegnato in una S.I.S.Te.M.A. radicale opera di miglioramento territoriale Cuneo come porta e infrastrutturale, è stato selezionato come .)#% transfrontaliera tra il sistema piattaforma territoriale trasfrontaliera oggetto territoriale del Piemonte del fi nanziamento che ha permesso l’attuazione meridionale, il territorio dell’idea-programma. -

MONASTÈRE DE SAORGE Le Couvent Des Franciscains Observantins Réformés Est L’Un Des Derniers Encore Conservés Dans Le Haut Pays Niçois

www.tourisme.monuments-nationaux.fr MONASTÈRE DE SAORGE Le couvent des Franciscains observantins réformés est l’un des derniers encore conservés dans le haut pays niçois. Le bourg de Saorge surplombe les gorges de la Roya. L’église du ACCÈS couvent des Franciscains fondé en 1633, est de style baroque ; le réfectoire conserve une décoration peinte du XVIIe siècle, et le cloître est orné de fresques du XVIIIe siècle illustrant la vie de Saint François d’Assise. Le Monastère conserve un ensemble intéressant de neuf cadrans solaires des XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. L’église présente l’un des plus anciens chemins de croix peints sur toile des Alpes-Maritimes. Depuis 2011, un jardin potager “bio”, aménagé en terrasse, est ouvert à la visite. ACCUEIL Horaires d’ouverture sous réserve de modifications. Ouvert De juin à septembre : de 10h à 12h30 et de 14h30 à 18h30 Axe Turin / Nice, en bordure de la D 6204 Du 1er octobre au 31 octobre et du 1er février au 30 avril : À 33 km au nord de Vintimille de 10h à 12h30 et de 14h30 à 17h30 De Nice : A8 et E74 jusqu’à Vintimille, Fermé Col de Tende-Breil, puis D6204 Du 1er novembre au 31 janvier 1er mai RENSEIGNEMENTS MONASTÈRE DE SAORGE SERVICES 06540 Saorge tél. : (33) (0)4 93 04 55 55 Possibilité de repos pendant la visite fax : (33) (0)4 93 04 52 37 Toilettes [email protected] Traversée de Saorge impossible en voiture www.monastere-saorge.fr Parking pour autocars 600 m (le car accède au parking par l’entrée nord du village), une partie du chemin en forte pente SUD EST PROVENCE-ALPES-CÔTE -

VALLÉE TANARO VALLÉES PESIO Et COLLA VALLÉE VERMENAGNA

VALLÉE TANARO MONDOVÌ et les VALLÉES MONREGALESI VALLÉES PESIO et COLLA VALLÉE VERMENAGNA Ormea - ph. G. Mignone Piazza Maggiore - Mondovì - ph. G. Gamberini Chartreuse de Pesio - ph. R. Croci À Mondovì et dans ses vallées, il y en a pour tous les goûts : situées Sans doute la plus connue des touristes, la vallée Vermenagna, entre les Alpes et les Langhe, elles sont ponctuées d’églises et de À quelques km de Cuneo, les vallées Pesio et Colla, accessibles aussi e notamment la partie haute, offre des paysages soignés et des forêts chapelles médiévales, riches en belles fresques du XV s., même le plus en vélo électrique, présentent des prairies verdoyantes et des forêts vertes, qui offrent une atmosphère chaleureuse et accueillante tout au petit bourg possède d’importantes églises paroissiales baroques, dont ombragées, mais aussi des sites riches en histoire plongés dans la Sa position géographique, entre les Langhe, la Ligurie et le Monregalese, long de l’année. Ce territoire est habité depuis l’époque romaine grâce à beaucoup ont été conçues par l’architecte local Francesco Gallo. nature. Habitée dès l’ère protohistorique, cette zone était organisée au confère à la vallée Tanaro une grande variété de paysages et d’influences la présence du col du mont Cornio (ou Col de Tende), facile à emprunter Moyen-âge en petits centres fortifiés avec des enceintes et des châteaux : culturelles. Les événements historiques du passé ont laissé des traces par les marchands et les voyageurs. sur les éperons rocheux, des ruines dominent encore les villages. La du passage de marcheurs et marchands, comme en témoigne le pont MONDOVÌ C’est une ville aux âmes multiples : une balade dans le Jusqu’au début du XVI e s., cette zone faisait partie du petit mais puissant dévotion des habitants et l’influence de la magnifique chartreuse de romain de Bagnasco. -

La Via Del Sale 2008.Pdf

La via del sale 2008:Limone 2007 17-06-2008 10:24 Pagina 1 LLAA VVIIAA DDEELL SSAALLEE La via del sale 2008:Limone 2007 17-06-2008 10:24 Pagina 2 LA VIA DEL SALE (E DEI BRIGANTI) renga ha quindi almeno 800 anni e può considerarsi una delle più antiche vie del sale. Il nome stesso di Colle delle Selle Vecchie è probabilmente la deformazio - el cuore delle Alpi Liguri, lungo il crinale che separa la pianura dal mare, ne dal francese di Col des Sels Vieils (colle dei vecchi sali) oppure Col des Sels, si sviluppa uno dei tracciati della «Via del Sale», così chiamata per il pre - le vieil (il vecchio colle dei sali). Nzioso minerale trasportato per secoli a dorso di mulo attraverso questi Dalla strada si diramavano numerose vie secondarie, sentieri e scorciatoie, che monti. Perché «Via del Sale»? Va ricordato che il sale, elemento base dell’ali - servivano a deviare i carichi di sale verso le varie destinazioni. La stessa strada mentazione umana e animale, è stato nei secoli più prezioso dell’oro, tanto che era percorsa da numerosi contrabbandieri, povera gente che cercava di trarre le piste del sale hanno costituito le grandi strade commerciali dell’antichità, in Eu - qualche guadagno per il sostentamento della famiglia commerciando clande - ropa come in Asia e in Africa. stinamente la preziosa materia prima. Le gole, i crocevia, gli anfratti, che si tro - Anche a Limone Piemonte il commercio di questa materia prima ha assunto vano numerosi lungo tutto il percorso, erano propizi ai numerosi agguati dei bri - grande importanza per via della posizione geografica del Piemonte, circondato ganti che depredavano del carico i mulattieri: sul Colle dei Signori, dietro l’at - per una metà dalle Alpi e senza alcuno sbocco verso il mare dall’altra. -

Illustrations of the Passes of the Alps”

Note di viaggio riferite agli anni 1826/1828 tratte da: “Illustrations of the passes of the Alps” by wich Italy communicates with France, Switzerland, Germany by William Brockedon F.R.S. member of the academies of fine arts at Florence and Rome London 1836 – II edition pagine 61-68 (la prima edizione è del 1828) Vol. II Capitolo The Tende and the Argentiere ROUTE FROM NICE TO TURIN, by THE PASS OF THE COL DE TENDE. NICE has long possessed the reputation of having a climate and a situation peculiarly favourable to those invalids who arrive there from more northern countries; a circumstance that probably led to the improvements of the road which lies between this city and Turin, by the Col de Tende. The situation of Nice is strikingly beautiful from many points of view in its neighbourhood, and many interesting remains of antiquity may be visited in short excursions from the city: these are sources of enjoyment within the reach of the valetudinarian, and add to the pleasures and advantages of a residence at Nice; but they are principally to be found coastways. The rich alluvial soil at the mouth of the Paglione, that descends from the Maritime Alps, gives a luxuriant character to the plain, which, near Nice, is covered with oranges, olives, vines, and other productions of a southern climate; but the moment this little plain is left, on the road to Turin, and the ascent commences towards Lascarene, the traveller must bid adieu to the country where "the oil and the wine abound." The sudden change to stones and sterility, with here and there a stunted, miserable-looking olive-tree, is very striking; and the eye scarcely finds any point of relief from this barrenness until the little valley appears in which Lascarene is situated. -

M Ar M Editerraneo M Er M É Diterran É E M Editerranean

Tête de la Mazelière 2881 M. Sautron Rocca Rossa Chiappera Sant Anna Morra San Bernardo L. du Lauzerot 2452 3166 2355 426 Centallo Pic de Charance Ponte Marmora Bonvicino M. Vallonasso Tarantasca Lovera 502 2316 743 Riserva Naturale dei Ciciu del Villar Réserve Collinaire Tête de Maralouches Fort de La Meyna 3034 1030 Rifugio Alpino Palent Lottulo Serre 451 Meyronnes 3067 2888 1526 St-Ours 2685 Colle del Sautron (Posto Tappa) Celle di Macra San Costanzo Le Belvédère San Quirico 637 Le Gros Ferrant Saint-Ours Col de Sautron M. Viraysse Ponte Maira M. BauveèSan Damiano Macra Rif. Privato al M.e L. di S.Anna La Madonnina 639 Belvedere Langhe de Sainte-Anne Saretto 1200 P.ta Cialier 1203 Villar San Costanzo 2401A B C D TêteE de Viraysse 2838 F G Prazzo M. Buch H 1270 I L M N O P Q R S 6°30’E 6°36’E 6°42’E 2210 6°48’E 6°54’E 7°00’E 7°06’E1728 7°12’E 7°18’ESanta Maria 7°24’E 7°30’E 7°36’E 7°42’E 7°48’E 7°54’E 8°00’E Le Petit Ferrant Pointe de Pémian Sainte-Anne Fort de 2771 L. de Viraysse Aiguille de Barsin 2111 P.ta Gordan 2560 P.ta le Teste P.ta Meleze 690 Delibera Morra del Villar 2440 2769 la Condamine Tournoux 2683 2595 P.ta Fornetti 1292 M 700 Murazzo Ceriolo San Bened Le Pouzenc 1746 a San Biagio La Batterie L. de la Reculaye 2701 1291 i 364 2898 Fort de Roche la Croix L. -

Traité De Paix Avec L'italie (10 Février 1947)

Traité de Paix avec l'Italie (10 février 1947) Légende: Le 10 février 1947, l'Italie signe à Paris le traité de paix, négocié avec le "Conseil des Quatre" puissances alliées (États-Unis, France, Grande-Bretagne et URSS), qui comporte des clauses territoriales et des stipulations concernant les réparations économiques. Source: Traité de paix avec l'Italie-Treaty of peace with Italy-Mirnyj dogovor s Italiej-Trattato di pace con l'Italia. [s.l.]: 1947 Copyright: Tous droits de reproduction, de communication au public, d'adaptation, de distribution ou de rediffusion, via Internet, un réseau interne ou tout autre moyen, strictement réservés pour tous pays. Les documents diffusés sur ce site sont la propriété exclusive de leurs auteurs ou ayants droit. Les demandes d'autorisation sont à adresser aux auteurs ou ayants droit concernés. Consultez également l'avertissement juridique et les conditions d'utilisation du site. URL: http://www.ena.lu/traite_paix_italie_10_fevrier_1947-1-988 www.ena.lu Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l'Europe (CVCE) 1 / 110 Traité de Paix avec l'Italie (10 février 1947) Traité de Paix avec l’Italie (1947) Les Etats-Unis d’Amérique, la Chine, la France, le Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d’Irlande du Nord, l’Union des Républiques Soviétiques Socialistes, l’Australie, la Belgique, la République Soviétique Socialiste de Biélorussie, le Brésil, la Canada, l’Ethiopie, la Grèce, l’Inde, la Nouvelle-Zélande, les Pays-Bas, la Pologne, la Tchécoslovaquie, la République Soviétique Socialiste d’Ukraine, l’Union Sud-Africaine, -

Guide Des Vallees Occitanes De La Province De Cuneo

guide des vallées occitanes de la province de Cuneo NUOVO, DA SEMPRE. La ligne verte délimite la partie du territoire qui est de compétence de l’A.T.L. du Cuneese. INDEX L’Occitanie page 3 Bienvenus dans les vallées occitanes de la Province de Cuneo ! »4 L’Occitanie à pied »5 VALLÉES PÔ, BRONDA, INFERNOTTO »6 Les noms du Mont Viso » 7 Du Mombracco au Buco di Viso » 8 À la découverte de la haute vallée » 9 Peintres en route » 10 Foi religieuse et légendes » 11 VAL VARAITA »12 Artisanat “solaire” » 13 Sous le Col de l’Agnel » 14 Casteldelfino et le bois de l’Alevé » 15 Poésies et rubans colorés » 16 Lys et dauphins » 17 Mistà et danse » 18 Les sons de la vallée » 19 VAL MAIRA »20 Une anglaise à Dronero » 21 Grands maîtres » 22 Les ciciu du Saint » 24 Musées de vallée » 26 Dans le village de Matteo Olivero » 27 Manger d’oc » 28 Un “espace”tout occitan » 29 VALLE GRANA »32 Fromage Castelmagno » 33 Sanctuaire de Castelmagno » 34 Novè »36 Fêtes à Coumboscuro » 37 Sur les traces de Pietro » 38 Caraglio: soie, musique et art » 39 VALLE STURA »42 Musées d’altitude » 43 Vinadio en mouvement » 44 Frontières de beurre » 45 Mémoires des Alpes en guerre » 46 Les merveilles de Pedona » 47 Parcours littéraires et légendes » 48 VALLE GESSO page 52 L’ours et le seigle » 53 Mémoires royales à Valdieri et Entracque » 54 Sur les traces des loups et des gypaètes » 57 Le Parlate, théâtre d’oc » 58 Gastronomie de vallée » 59 Histoire de bergers migrants » 60 VAL VERMENAGNA »62 Les Forts de Tende » 63 Ubi stabant cathari »64 Pinocchio à Vernante » 65 Le génie -

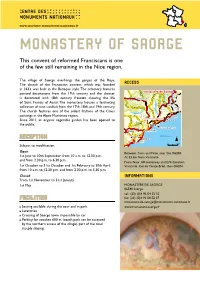

MONASTERY of SAORGE This Convent of Reformed Franciscans Is One of the Few Still Remaining in the Nice Region

www.tourisme.monuments-nationaux.fr MONASTERY OF SAORGE This convent of reformed Franciscans is one of the few still remaining in the Nice region. The village of Saorge overhangs the gorges of the Roya. ACCESS The church of the Franciscan convent, which was founded in 1633, was built in the Baroque style. The refectory features painted decorations from the 17th century and the cloister is decorated with 18th century frescœs showing the life of Saint Francis of Assisi. The monastery houses a fascinating collection of nine sundials from the 17th, 18th, and 19th century. The church features one of the oldest Stations of the Cross paintings in the Alpes-Maritimes region. Since 2011, an organic vegetable garden has been opened to the public. RECEPTION Subject to modification. Open Between Turin and Nice, near the D6204 1st June to 30th September: from 10 a.m. to 12.30 p.m. At 33 km from Vintimille and from 2.30 p.m. to 6.30 p.m. From Nice: A8 motorway and E74 direction 1st October to 31st October and 1st February to 30th April: Vintimille, Col de Tende-Breil, then D6204 from 10 a.m. to 12.30 p.m. and from 2.30 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. Closed INFORMATIONS From 1st November to 31st January 1st May MONASTÈRE DE SAORGE 06540 Saorge tel.: (33) (0)4 93 04 55 55 FACILITIES fax: (33) (0)4 93 04 52 37 [email protected] Seating available during the tour and in park www.monastere-saorge.fr Lavatories Crossing of Saorge town impossible by car Parking for coaches 600 m (coach park can be accessed by the northern access of the village), part of the road steeply sloping SOUTH EASTERN FRANCE PROVENCE-ALPES-CÔTE D’AZUR / MONASTERY OF SAORGE TOURS Unaccompanied tour with guide booklet French, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Dutch Duration: 40 min Guided tour (gardens included) French, English, Italian Visits (subject to modifications): ACCESS High season (June to September): 10.45 a.m., 2.30 p.m., 3.30 p.m., 4.30 p.m. -

Cuneo Caraglio Dronero Demonte Borgo San Dalmazzo Barcelonnette

Cima del Pelvo Punta Vergia Scalenghe La Grande Roche du Lauzon Monte Cialmetta San Bernardo Pointe du Sélé Saint-Antoine 1260 262 La Rouya Cervières 3264 2992 Punta Gardetta Malanaggio L’Olan Mont Gioberney 3556 274-578 1831 Pointe Guyard Villar-Saint-Pancrace 2335 2737 Monte Servin Rif. Vaccera a 3350 B 1468 in A B 2751C D n ria F G H I Monte Freidour L M Monte Craviale N O P m Q R 35646°12’E Cime du Vallon Ref. du6°18’E Pigeonnier 3461 6°24’E 6°30’E o n 6°48’ECima Dormillouse 6°54’E 7°00’E 7°06’E 7°12’E 7°18’E 7°24’E 7°30’Ee 7°36’E 7°42’E Pointe du Rascrouset La Blanche ç ço Turge de Peyron 1756 Gaido L Aiguille des Saffres an n 2571 Rif. Jumarre 787 Miradolo 376 3418 ri 2908 Buriasco 1 3135 3082 2954 B Bric Froid 301 Sommet Sud des Bans Puy Aillaud 2791 Lem Pic du Lauzon Tête d’Amont ina Ref. de l’Olan Ref. de Chalance 4 Cime de la Charvie Monte Terra Nera Prarostino Osasio 2344 2560 Chalet Ref. 3669 3302 Punta Cialancia Punta Rognosa Pinerolo 245 413 241 2949 du Globerney 2814 Rif. Alpino 738 San Luigi 2881 3100 ai Sap Virle Piemonte Piton de la Viaclose Vallouise 2855 1321 San Secondo Lem o Le villard ina SP 663 P l a S e 1200 Punta Merciantaria Cima Frappier Baudenasca nd D 904 di Pinerolo 3010 Ref. des Bans L’O d e é Le Petit Peygu Cercenasco l é e 2083 Pic Charbonnel 3003 Punta Cornour Rif. -

Télécharger La Fiche Complète

BASE DE DONNEES DES BIENS IMMOBILIERS Référencement du bien Code base données FO-1-I-f-En-A1-V1-2 Dénomination Ouvrages ferroviaires PLM de Fontan - Saorge Type Bâtiment / Ouvrage d’art / Site aménagé Localisation 1) Gare : Route RD 38, entre le village de Fontan et celui de Saorge 2) Autres ouvrages : voir cartographie Coordonnées GPS 1) Gare : 43°59’48’’ N – 7°33’06.5’’ E 2) Autres ouvrages : voir cartographie Nature Système d’ouvrages à vocation semblable Vocation initiale Civile / Industrielle Vocation actuelle Civile / Industrielle Usage initial Transport de passagers et de fret. Usage actuel Transport de passagers, affectations diverses. Propriétaire SNCF Protection légale Pas de protection officielle hormis servitude SNCF Mots clés Fontan, Saorge, Roya, chemin de fer, gare, voie ferrée, ferroviaire, train, viaduc, tunnel, boucle de Berghe, Scarassoui. Informations sur la situation du bien Accès 1) Gare : Au départ de la route RD 6204 dans le village, prendre la route RD 38. 2) Autres ouvrages : souvent visibles depuis la route RD 6204. Voir cartographie Eléments cartographiques Localisation de la gare de Fontan – Saorge entre les deux villages. (© geopotail.gouv.fr) Tracé de le boucle ferroviaire hélicoïdale de Berghe et localisation du viaduc de Scarassoui, au nord de Fontan. (© geopotail.gouv.fr) Localisation du viaduc de Saorge au sud, et de la gare de Fontan-Saorge plus au nord. (© geopotail.gouv.fr) Contexte / 1) La gare de Fontan-Saorge a nécessité d’importants terrassements dans la implantation pente naturelle du site, pour la création d’une plateforme pouvant accueillir la gare, les voies et les bâtiments annexes, à l’altitude souhaitée. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 01:06:06PM Via Free Access

Contributions to Zoology 89 (2020) 270-281 CTOZ brill.com/ctoz Environmental correlates of the European common toad hybrid zone Jan W. Arntzen Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] Daniele Canestrelli Department of Ecological and Biological Science, Largo dell’Università s.n.c., 01100 Viterbo, Italy [email protected] Iñigo Martínez-Solano Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands Department of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, c/ José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain [email protected] Abstract The interplay between intrinsic (development, physiology, behavior) and extrinsic (landscape features, climate) factors determines the outcome of admixture processes in hybrid zones, in a continuum from complete genetic merger to full reproductive isolation. Here we assess the role of environmental corre- lates in shaping admixture patterns in the long hybrid zone formed by the toads Bufo bufo and B. spinosus in western Europe. We used species-specific diagnostic SNP markers to genotype 6584 individuals from 514 localities to describe the contact zone and tested for association with topographic, bioclimatic and land use variables. Variables related to temperature and precipitation contributed to accurately predict the distribution of pure populations of each species, but the models did not perform well in areas where genetically admixed populations occur. A sliding window approach proved useful to identify different sets of variables that are important in different sections of this long and heterogeneous hybrid zone, and offers good potential to predict the fate of moving contact zones in global change scenarios.