Aboriginal Astronomy: WA Focus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15Th October at 19:00 Hours Or 7Pm AEST

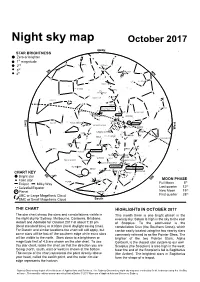

TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 URSA MINOR CEPHEUS CASSIOPEIA DRACO Night sky map OctoberDRACO 2017 URSA MAJOR North North STAR BRIGHTNESS Zero or brighter 1st magnitude nd LACERTA Deneb 2 NE rd NE Vega CYGNUS CANES VENATICI LYRAANDROMEDA 3 Vega NW th NW 4 LYRA LEO MINOR CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES VULPECULA COMA BERENICES Arcturus PEGASUS SAGITTA DELPHINUS SAGITTA SERPENS LEO Altair EQUULEUS PISCES Regulus AQUILAVIRGO Altair OPHIUCHUS First Quarter Moon SERPENS on the 28th Spica AQUARIUS LIBRA Zubenelgenubi SCUTUM OPHIUCHUS CORVUS Teapot SEXTANS SERPENS CAPRICORNUS SERPENSCRATER AQUILA SCUTUM East East Antares SAGITTARIUS CETUS PISCIS AUSTRINUS P SATURN Centre of the Galaxy MICROSCOPIUM Centre of the Galaxy HYDRA West SCORPIUS West LUPUS SAGITTARIUS SCULPTOR CORONA AUSTRALIS Antares GRUS CENTAURUS LIBRA SCORPIUS NORMAINDUS TELESCOPIUM CORONA AUSTRALIS ANTLIA Zubenelgenubi ARA CIRCINUS Hadar Alpha Centauri PHOENIX Mimosa CRUX ARA CAPRICORNUS TRIANGULUM AUSTRALEPAVO PYXIS TELESCOPIUM NORMAVELALUPUS FORNAX TUCANA MUSCA 47 Tucanae MICROSCOPIUM Achernar APUS ERIDANUS PAVO SMC TRIANGULUM AUSTRALE CIRCINUS OCTANSCHAMAELEON APUS CARINA HOROLOGIUMINDUS HYDRUS Alpha Centauri OCTANS SouthSouth CelestialCelestial PolePole VOLANS Hadar PUPPIS RETICULUM POINTERS SOUTHERN CROSS PISCIS AUSTRINUS MENSA CHAMAELEONMENSA MUSCA CENTAURUS Adhara CANIS MAJOR CHART KEY LMC Mimosa SE GRUS DORADO SMC CAELUM LMCCRUX Canopus Bright star HYDRUS TUCANA SWSW MOON PHASE Faint star VOLANS DORADO -

Aboriginal History Journal

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Editor Shino Konishi, Book Review Editor Luise Hercus, Copy Editor Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, are welcomed. Subjects include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, archival and bibliographic articles, and book reviews. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, Coombs Building (9) ANU, ACT, 0200, or [email protected]. -

0 Report of an Aboriginal Heritage Survey for the Armadale Road Duplication Project in the City of Armadale and City of Cockburn, Western Australia

REPORT OF AN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE SURVEY FOR THE ARMADALE ROAD DUPLICATION PROJECT IN THE CITY OF ARMADALE AND CITY OF COCKBURN, WESTERN AUSTRALIA A report prepared for Main Roads Western Australia By Ms Louise Huxtable Consulting Anthropologist 79 Naturaliste Terrace DUNSBOROUGH WA 6281 [email protected] Mr Thomas O’Reilly Consulting Archaeologist 250 Barker Road SUBIACO WA 6008 [email protected] Report submitted March 2017 to: Mr Brian Norris Principal Project Manager, Transport WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff Level 5 503 Murray Street PERTH WA 6000 The Registrar Department of Aboriginal Affairs PO Box 3153 151 Royal Street EAST PERTH WA 6892 0 REPORT OF AN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE SURVEY FOR THE ARMADALE ROAD DUPLICATION PROJECT IN THE CITY OF ARMADALE AND CITY OF COCKBURN, WESTERN AUSTRALIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank the following organisations and individuals who helped with the management of this Aboriginal heritage survey: Mr John Braid – Main Roads Western Australia (Principal Environment Officer) Ms Marni Baetge – Main Roads Western Australia (Environment Officer) Mr Sergio Martinez – Main Roads Western Australia (Project Manager) Mr Todd Craig – Main Roads Western Australia (Principal Heritage Officer) Mr JJ McDermott – Main Roads Western Australia (Heritage Contractor) Mr Brian Norris – WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff (Project Manager) Ms Hayley Martin – WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff (Civil Engineer) Ms Orlagh Brady – WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff (Graduate Civil Engineer) Ms Lyndall Ford – Department of Aboriginal -

![[2001] Wamw 19 Calder Sm](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3575/2001-wamw-19-calder-sm-93575.webp)

[2001] Wamw 19 Calder Sm

[2001] WAMW 19 CALDER SM JURISDICTION : MINING WARDEN TITLE OF COURT : OPEN COURT LOCATION : PERTH CITATION : NORMANDY BOW RIVER DIAMOND MINE LTD -v- CLINTON ANDELA (2001) WAMW15 CORAM : CALDER SM HEARD : 5-6 OCTOBER, 6 NOVEMBER 2000 AND 8-9 FEBRUARY 2001 DELIVERED : 16 AUGUST 2001 FILE NO/S : APPLICATIONS FOR EXEMPTION 10/990 TO 18/990 TENEMENT NO/S : MINING LEASES 80/108 TO 113; EXPLORATION LICENCES 80/2054, 80/2084-5 BETWEEN : NORMANDY BOW RIVER DIAMOND MINE LTD Applicant AND CLINTON ANDELA Objector Catchwords: EXPLORATION LICENCE - exemption – obtaining approvals EXPLORATION LICENCE - exemption - time required EXEMPTION - exploration licence – obtaining approvals EXEMPTION - exploration licence - time required EXEMPTION - mining lease – obtaining approvals Document Name: [2001]WAMW19.doc Normandy v Andela CM Page 1 [2001] WAMW 19 CALDER SM EXEMPTION - mining lease - time required MINING LEASE - exemption – obtaining approvals MINING LEASE - exemption - time required Legislation: MINING ACT 1978 (WA) - s 102(2)(b) MINING ACT 1978 (WA) - s 102(2)(g) Result: Representation: Counsel: Mr R.M. Edel for the applicant Mr M.P. Workman for the objector Solicitors: Gadens Lawyers for the applicant Michael Workman for the objector Case(s) referred to in judgment(s): Re Heaney; ex parte Tunza Holdings Pty Ltd (1997) 18 WAR 420 Ward and Others v State of Western Australia and Others 159 ALR 483 Case(s) also cited: Document Name: [2001]WAMW19.doc Normandy v Andela CM Page 2 [2001] WAMW 19 CALDER SM REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE WARDEN FOR THE MINISTER - S102(5) MINING ACT 1978 THE PROCEEDINGS 1 Normandy Bow River Diamond Mine Ltd ("Normandy") has made application for the grant of certificates of exemption in respect of mining leases 80/108 to 113 inclusive for the expenditure year ended 28 July 1999 in respect of each mining lease. -

02 Southern Cross

Asterism Southern Cross The Southern Cross is located in the constellation Crux, the smallest of the 88 constellations. It is one of the most distinctive. With the four stars Mimosa BeCrux, Ga Crux, A Crux and Delta Crucis, forming the arms of the cross. The Southern Cross was also used as a remarkably accurate timepiece by all the people of the southern hemisphere, referred to as the ‘Southern Celestial Clock’ by the portuguese naturalist Cristoval D’Acosta. It is perpendicular as it passes the meridian, and the exact time can thus be calculated visually from its angle. The german explorer Baron Alexander von Humboldt, sailing across the southern oceans in 1799, wrote: “It is a timepiece, which advances very regularly nearly 4 minutes a day, and no other group of stars affords to the naked eye an observation of time so easily made”. Asterism - An asterism is a distinctive pattern of stars or a distinctive group of stars in the sky. Constellation - A grouping of stars that make an imaginary picture in the sky. There are 88 constellations. The stars and objects nearby The Main-Themes in asterism Southern Cross Southern Cross Ga Crux A Crux Mimosa, Be Crux Delta Crucis The Motives in asterism Southern Cross Crucis A Bayer / Flamsteed indication AM Arp+Madore - A Catalogue of Southern peculiar Galaxies and Associations [B10] Boss, 1910 - Preliminary General Catalogue of 6188 Stars C Cluster CCDM Catalogue des composantes d’étoiles doubles et multiples CD Cordoba Durchmusterung Declination Cel Celescope Catalog of ultraviolet Magnitudes CPC -

Hunting Down Stars with Unusual Infrared Properties Using Supervised Machine Learning

. Magnificent beasts of the Milky Way: Hunting down stars with unusual infrared properties using supervised machine learning Julia Ahlvind1 Supervisor: Erik Zackrisson1 Subject reader: Eric Stempels1 Examiner: Andreas Korn1 Degree project E in Physics { Astronomy, 30 ECTS 1Department of Physics and Astronomy { Uppsala University June 22, 2021 Contents 1 Background 2 1.1 Introduction................................................2 2 Theory: Machine Learning 2 2.1 Supervised machine learning.......................................3 2.2 Classification...............................................3 2.3 Various models..............................................3 2.3.1 k-nearest neighbour (kNN)...................................3 2.3.2 Decision tree...........................................4 2.3.3 Support Vector Machine (SVM)................................4 2.3.4 Discriminant analysis......................................5 2.3.5 Ensemble.............................................6 2.4 Hyperparameter tuning.........................................6 2.5 Evaluation.................................................6 2.5.1 Confusion matrix.........................................6 2.5.2 Precision and classification accuracy..............................7 3 Theory: Astronomy 7 3.1 Dyson spheres...............................................8 3.2 Dust-enshrouded stars..........................................8 3.3 Gray Dust.................................................9 3.4 M-dwarf.................................................. 10 3.5 post-AGB -

I Nomi Delle Stelle

I nomi delle stelle Se state leggendo questa pagina perché volete acquistare il nome di una stella, visitate IAU Theme Buying Stars and Star Names. Altrimenti, proseguite con il testo sottostante. L'UAI intende delineare una distinzione tra i termini nome e designazione. In questo testo, così come in altre pubblicazioni dell'UAI, il nome si riferisce al termine (solitamente colloquiale) utilizzato per una stella nel linguaggio quotidiano, mentre la designazione è esclusivamente alfanumerica e viene usata quasi esclusivamente nei cataloghi ufficiali e nell'astronomia professionale. Storia dei cataloghi stellari La catalogazione delle stelle ha una lunga storia alle spalle. Sin dalla preistoria, culture e civiltà in tutto il mondo hanno dato dei propri nomi alle stelle più luminose e importanti nel cielo notturno. Attraversando le culture greca, latina e araba, alcuni nomi hanno subito pochi cambiamenti e altri sono in uso ancora oggi. Mentre l'astronomia si sviluppava e si evolveva nel corso dei secoli, sorgeva la necessità di un sistema di catalogazione universale, in base al quale le stelle più luminose (e quindi quelle più studiate) fossero conosciute secondo gli stessi appellativi, indipendentemente dal Paese o dalla cultura da cui provenivano gli astronomi. Per risolvere questo problema, gli astronomi durante il Rinascimento hanno tentato di produrre cataloghi stellari seguendo un insieme di regole. Il primo esempio, ancora oggi popolare, è stato introdotto da Johann Bayer nel suo atlante Uranometria del 1603. Bayer ha catalogato le stelle in ogni costellazione con lettere greche minuscole, seguendo l'ordine approssimativo della loro luminosità apparente, in modo che la stella più luminosa di una costellazione fosse solitamente (ma non sempre) etichettata come Alpha, la seconda più brillante fosse Beta, e così via. -

Extremely Extended Dust Shells Around Evolved Intermediate Mass Stars: Probing Mass Loss Histories,Thermal Pulses and Stellar Evolution

EXTREMELY EXTENDED DUST SHELLS AROUND EVOLVED INTERMEDIATE MASS STARS: PROBING MASS LOSS HISTORIES,THERMAL PULSES AND STELLAR EVOLUTION A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by BASIL MENZI MCHUNU Dr. Angela K. Speck December 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled: EXTREMELY EXTENDED DUST SHELLS AROUND EVOLVED INTERMEDIATE MASS STARS PROBING MASS LOSS HISTORIES, THERMAL PULSES AND STELLAR EVOLUTION USING FAR-INFRARED IMAGING PHOTOMETRY presented by Basil Menzi Mchunu, a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Angela K. Speck Dr. Sergei Kopeikin Dr. Adam Helfer Dr. Bahram Mashhoon Dr. Haskell Taub DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my family, who raised me to be the man I am today under challenging conditions: my grandfather Baba (Samuel Mpala Mchunu), my grandmother (Ma Magasa, Nonhlekiso Mchunu), my aunt Thembeni, and my mother, Nombso Betty Mchunu. I would especially like to thank my mother for all the courage she gave me, bringing me chocolate during my undergraduate days to show her love when she had little else to give, and giving her unending support when I was so far away from home in graduate school. She passed away, when I was so close to graduation. To her, I say, ′′Ulale kahle Macingwane.′′ I have done it with the help from your spirit and courage. I would also like to thank my wife, Heather Shawver, and our beautiful children, Rosemary and Brianna , for making me see life with a new meaning of hope and prosperity. -

Documentation of Northern Alta: Grammar, Texts and Glossary

Documentation of Northern Alta: grammar, texts and glossary Alexandro-Xavier García Laguía ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

The Sky Tonight

MARCH POUTŪ-TE-RANGI HIGHLIGHTS Conjunction of Saturn and the Moon A conjunction is when two astronomical objects appear close in the sky as seen THE- SKY TONIGHT- - from Earth. The planets, along with the TE AHUA O TE RAKI I TENEI PO Sun and the Moon, appear to travel across Brightest Stars our sky roughly following a path called the At this time of the year, we can see the ecliptic. Each body travels at its own speed, three brightest stars in the night sky. sometimes entering ‘retrograde’ where they The brightness of a star, as seen from seem to move backwards for a period of time Earth, is measured as its apparent (though the backwards motion is only from magnitude. Pictured on the cover is our vantage point, and in fact the planets Sirius, the brightest star in our night sky, are still orbiting the Sun normally). which is 8.6 light-years away. Sometimes these celestial bodies will cross With an apparent magnitude of −1.46, paths along the ecliptic line and occupy the this star can be found in the constellation same space in our sky, though they are still Canis Major, high in the northern sky. millions of kilometres away from each other. Sirius is actually a binary star system, consisting of Sirius A which is twice the On March 19, the Moon and Saturn will be size of the Sun, and a faint white dwarf in conjunction. While the unaided eye will companion named Sirius B. only see Saturn as a bright star-like object (Saturn is the eighth brightest object in our Sirius is almost twice as bright as the night sky), a telescope can offer a spectacular second brightest star in the night sky, view of the ringed planet close to our Moon. -

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. -

Beverages Bridal Apparel Cakes Calligraphy Catering

BEVERAGES Espresso Dave’s Specialty Coffee Catering Dave Salzman • espressodave.com FLORAL DESIGN [email protected] • 888-221-9029 Artistic Blossoms Floral Design Studio Kelly Dolloff • artisticblossoms.com Gordon’s Fine Wines & Liquors [email protected] • 781-837-6251 Leslie Lamb • gordonswine.com [email protected] • 781-893-6700 x1 Jeri Solomon Floral Design Jeri Solomon • jerifloraldesign.com Revolution Cocktails [email protected] • 781-435-1410 Patrick Sullivan • revolutioncocktails.com [email protected] • 781-939-6977 Mimosa Fresh Flower Design Christina Cheung • mimosastyle.com BRIDAL APPAREL [email protected] • 617-751-0855 Bella Sera Bridal Lisa Almeida • bellaserabride.com GOWN PRESERVATION [email protected] • 978-774-4077 Dependable Cleaners Elton Crespo • dependablecleaners.com Shoes to Dye For [email protected] • 617-698-8300 Ron Davis • shoestodyefor.com [email protected] • 888-393-2253 HAIR STYLING Blondie Brides Tuxedos by Merian Krysten Deveaux • blondiesalonandspa.com Paul Merian • tuxedostoyou.com [email protected] • 781-464-0064 [email protected] • 508-612-2687 Demiche CAKES Michelle De Voe • demiche.com Cakes for Occasions [email protected] • 781-662-1796 Katrina O’donnell • cakes4occasions.com [email protected] • 978-774-4545 Studio 9 Debbie Welch • studio9boston.com Jenny’s Wedding Cakes [email protected] • 617-267-9990 Jennifer Williamson • jencakes.com [email protected] • 978-269-7195 INVITATIONS Invitations