Tcherkezian Kathleen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

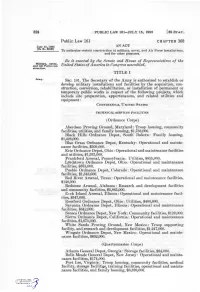

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

Jeannie Leavitt, MWAOHI Interview Transcript

MILITARY WOMEN AVIATORS ORAL HISTORY INITIATIVE Interview No. 14 Transcript Interviewee: Major General Jeannie Leavitt, United States Air Force Date: September 19, 2019 By: Lieutenant Colonel Monica Smith, USAF, Retired Place: National Air and Space Museum South Conference Room 901 D Street SW, Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20024 SMITH: I’m Monica Smith at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Today is September 19, 2019, and I have the pleasure of speaking with Major General Jeannie Leavitt, United States Air Force. This interview is being taped as part of the Military Women Aviators Oral History Initiative. It will be archived at the Smithsonian Institution. Welcome, General Leavitt. LEAVITT: Thank you. SMITH: So let’s start by me congratulating you on your recent second star. LEAVITT: Thank you very much. SMITH: You’re welcome. You’re welcome. So you just pinned that [star] on this month. Is that right? LEAVITT: That’s correct, effective 2 September. SMITH: Great. Great. So that’s fantastic, and we’ll get to your promotions and your career later. I just have some boilerplate questions. First, let’s just start with your full name and your occupation. LEAVITT: Okay. Jeannie Marie Leavitt, and I am the Commander of Air Force Recruiting Service. SMITH: Fantastic. So when did you first enter the Air Force? LEAVITT: I was commissioned December 1990, and came on active duty January 1992. SMITH: Okay. And approximately how many total flight hours do you have? LEAVITT: Counting trainers, a little over 3,000. SMITH: And let’s list, for the record, all of the aircraft that you have piloted. -

Meet Tomorrow's Military Aviators We're Proud to Highlight These Daedalian Matching Scholarship Recipients Who Are Pursuing Careers As Military Aviators

Daedalian Quick Links Website | Membership Application | Scholarship Application | Make a Donation | Pay Dues | Magazine AUGUST 2018 Meet tomorrow's military aviators We're proud to highlight these Daedalian Matching Scholarship recipients who are pursuing careers as military aviators. They are our legacy! If you would like to offer career advice or words of encouragement to these future aviators, please email us at [email protected] and we'll pass them on to the cadets. Cadet Jeffrey Iraheta Colorado State University $1,850 scholarship Mile High Flight 18 "I am hoping to become a first generation pilot and military member in my family. Currently I have been accepted to attend pilot training as of February 2018 when I commission in May 2019. I hope to make a career in the Air Force and go over 20 years of active duty time in order to give back to this country." Cadet Corum Krebsbach University of Central Florida $7,250 scholarship George "Bud" Day Flight 61 "My career goals are to join the United States Air Force as an officer through ROTC and go through flight school to become a fighter pilot, or any other kind of pilot if I cannot become a fighter pilot. I wish to be a pilot in the Air Force as long as I possibly can. After retirement, I plan to work either as a civilian contractor for the Air Force through Boeing or Lockheed-Martin or another aerospace company, or possibly work for NASA." Cadet Sierra Legendre University of West Florida $7,250 scholarship George "Bud" Day Flight 61 "My goal is to be a career pilot in the United States Air Force. -

Southern Arizona Military Assets a $5.4 Billion Status Report Pg:12

Summer 2014 TucsonChamber.org WHAT’S INSIDE: Higher State Standards Southern Arizona Military Assets 2nd Session/51st Legislature Improve Southern Arizona’s A $5.4 Billion Status Report pg:12 / Report Card pg:22 / Economic Outlook pg:29 B:9.25” T:8.75” S:8.25” WHETHER YOU’RE AT THE OFFICE OR ON THE GO, COX BUSINESS KEEPS YOUR B:11.75” S:10.75” BUSINESS RUNNING. T:11.25” In today’s world, your business counts on the reliability of technology more than ever. Cox Business provides the communication tools you need for your company to make sure your primary focus is on what it should be—your business and your customers. Switch with confidence knowing that Cox Business is backed by our 24/7 dedicated, local customer support and a 30-day Money-Back Guarantee. BUSINESS INTERNET 10 /mo* AND VOICE $ • Internet speeds up to 10 Mbps ~ ~ • 5 Security Suite licenses and 5 GB of 99 Online Backup FREE PRO INSTALL WITH • Unlimited nationwide long distance A 3-YEAR AGREEMENT* IT’S TIME TO GET DOWN TO BUSINESS. CALL 520-207-9576 OR VISIT COXBUSINESS.COM *Offer ends 8/31/14. Available to new customers of Cox Business VoiceManager℠ Office service and Cox Business Internet℠ 10 (max. 10/2 Mbps). Prices based on 1-year service term. Equipment may be required. Prices exclude equipment, installation, taxes, and fees, unless indicated. Phone modem provided by Cox, requires electricity, and has battery backup. Access to E911 may not be available during extended power outage. Speeds not guaranteed; actual speeds vary. -

General James V. Hartinger

GENERAL JAMES V. HARTINGER Retired July 31, 1984. Died Oct. 9, 2000. General James V. Hartinger is commander of the U.S. Air Force Space Command and commander in chief of the North American Aerospace Defense Command, with consolidated headquarters at Peterson Air Force Base, Colo. General Hartinger was born in 1925, in Middleport, Ohio, where he graduated from high school in 1943. He received a bachelor of science degree from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, N.Y., in 1949, and a master's degree in business administration from The George Washington University, Washington, D.C., in 1963. The general is also a graduate of Squadron Officer School at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., in 1955 and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces at Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C., in 1966. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in July 1943 and attained the grade of sergeant while serving in the Infantry. Following World War II he entered the academy and upon graduation in 1949 was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force. General Hartinger attended pilot training at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas, and Williams Air Force Base, Ariz., where he graduated in August 1950. He then was assigned as a jet fighter pilot with the 36th Fighter-Bomber Wing at Furstenfeldbruck Air Base, Germany. In December 1952 the general joined the 474th Fighter-Bomber Wing at Kunsan Air Base, South Korea. While there he flew his first combat missions in F-84 Thunderjets. Returning to Williams Air Force Base in July 1953, he served as a gunnery instructor with the 3526th Pilot Training Squadron. -

Brigadier General Randall K. "Randy" Bigum

BRIGADIER GENERAL RANDALL K. "RANDY" BIGUM BRIGADIER GENERAL RANDALL K. "RANDY" BIGUM Retired Oct. 1, 2001. Brig. Gen. Randall K. "Randy" Bigum is director of requirements, Headquarters Air Combat Command, Langley Air Force Base, Va. As director, he is responsible for all functions relating to the acquisition of weapons systems for the combat air forces, to include new systems and modifications to existing systems. He manages the definition of operational requirements, the translation of requirements to systems capabilities and the subsequent operational evaluation of the new or modified systems. He also chairs the Combat Air Forces Requirements Oversight Council for modernization investment planning. He directs a staff of seven divisions, three special management offices and three operating locations, and he actively represents the warfighter in defining future requirements while supporting the acquisition of today's combat systems. The general was born in Lubbock, Texas. A graduate of Ohio State University, Columbus, with a bachelor of science degree in business, he entered the Air Force in 1973. He served as commander of the 53rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Bitburg Air Base, Germany, the 18th Operations Group at Kadena Air Base, Japan, and the 4th Fighter Wing at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, S.C. He has served at Headquarters Tactical Air Command and the Pentagon, and at U.S. European Command in Stuttgart- Vaihingen where he was executive officer to the deputy commander in chief. The general is a command pilot with more than 3,000 flight hours in fighter aircraft. He flew more than 320 combat hours in the F- 15C during Operation Desert Storm. -

Transfer of Training with Formation Flight Trainer. INSTITUTION Air Force Human Resources Lab.; Williams AFB, Ariz

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 109 451 CE 004 301 AUTHOR Reid, Gary B.; Cyrus, Michael L. TITLE Transfer of Training with Formation Flight Trainer. INSTITUTION Air Force Human Resources Lab.; Williams AFB, Ariz. Flying Training Div. REPORT NO AFHRL-TP-74-102 PUB DATE Dec 74 NOTE 15p. EDRS PPICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aircraft Pilots; *Flight Training; *Simulation; *Skill Development; Training Techniques; *Transfer of Training ABSTRACT The.present research was conducted to determine transfer of practice from a formation simulator to actual aircraft flight for the wing aircraft component of the formation flying task. Evidence in support of positive transfer was obtained by comparing students trained in the formation simulator with students who were essentially untrained and with students trained in the aircraft. This design provided dat'S for a direct comparison of five simulator sorties with two aircraft sorties in an effort to quickly establish a training cost/transfer comparison. The results indicate that the simulator has at least the training effectiveness of two aircraft sorties. (Author/JB) AFHRL-TR-74-102 AIR FORCE TRANSFER OF TRAINING WITH FORMATION FLIGHT TRAINER HUMAN By Gary B. Reid Michael L. Cyrus FLYING TRAINING DIVISION Williams Air Force Base, Arizona 85224 . RESOURCESDecember 1974 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. LABORATORY AIR FORCE SYSTEMS COMMAND BROOKS AIR FORCE BASE,TEXAS 78235 NOTICE When US Government drawing, specifications, or other data are used for oany purpose other than a definitely related Government procurement operation, the Government thereby incurs no responsibility .nor any obligation whatsoever, and the fact that the Government may have formulated, furnished, or in any way supplied the said drawings, specifications, or other data is no to be regarded by implication or otherwise, as in any manner licensing the holder or any other person or corporation, or conveying any rights or permission to manufacture, use, or sell any patented invention that may in any way be related thereto. -

Before, During and After Sandy Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts Pages 8-13

AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 21 • Number 1 • Winter 2013 Before, During and After Sandy Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts Pages 8-13 In Review: 44th Annual A/TA Convention and the 2012 AMC and A/TA Air Mobility Symposium & Technology Exposition Pages 16-17 CONTENTS… Association News Chairman’s Comments ........................................................................2 President’s Message ...............................................................................3 Secretary’s Notes ...................................................................................3 Association Round-Up ..........................................................................4 AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 21 • Number 1 • Winter 2013 Cover Story Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published four times a year by the Airlift/Tanker Association, Before, During and After Sandy 9312 Convento Terrace, Fairfax, Virginia 22031. Postage paid at Belleville, Illinois. Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts ...8-13 Subscription rate: $40.00 per year. Change of address requires four weeks notice. The Airlift/Tanker Association is a non-profit Features professional organization dedicated to providing a forum for people interested in improving the capability of U.S. air mobility forces. Membership CHANGES AT THE TOP in the Airlift/Tanker Association is $40 annually or $110 for three years. Full-time student Air Mobility Command and membership is $15 per year. Life membership is 18th Air Force Get New Commanders ..........................................6-7 $500. Industry Partner membership includes five individual memberships and is $1500 per year. Membership dues include a subscription to Airlift/ An Interview with Lt Gen Darren McDew, 18AF/CC ...............14-15 Tanker Quarterly, and are subject to change. by Colonel Greg Cook, USAF (Ret) Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published for the use of subscribers, officers, advisors and members of the Airlift/Tanker Association. -

Fall 2015, Vol

Fall 2015, Vol. LVI No.3 CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 04 06 Newsbeat Daedalian Citation of Honor 05 09 Commander’s Perspective The WASP Uniforms 06 15 Adjutant’s Column Experiences of being among the first fifty 07 female pilots in the modern Air Force Linda Martin Phillips Book Reviews 08 34 Jackie Cochran Caitlin’s Corner 35 10 Chuck Yeager Awards Jack Oliver 18 Flightline America’s Premier Fraternal Order of Military Pilots 36 Promoting Leadership in Air and Space New/Rejoining Daedalians 37 Eagle Wing/Reunions 38 In Memoriam 39 Flight Addresses THE ORDER OF DAEDALIANS was organized on 26 March 1934 by a representative group of American World War I pilots to perpetuate the spirit of patriotism, the love of country, and the high ideals of sacrifice which place service to nation above personal safety or position. The Order is dedicated to: insuring that America will always be preeminent in air and space—the encourage- ment of flight safety—fostering an esprit de corps in the military air forces—promoting the adoption of military service as a career—and aiding deserving young individuals in specialized higher education through the establishment of scholarships. THE DAEDALIAN FOUNDATION was incorporated in 1959 as a non-profit organization to carry on activities in furtherance of the ideals and purposes of the Order. The Foundation publishes the Daedalus Flyer and sponsors the Daedalian Scholarship Program. The Foundation is a GuideStar Exchange member. The Scholarship Program recognizes scholars who indicate a desire to become military pilots and pursue a career in the military. Other scholarships are presented to younger individuals interested in aviation but not enrolled in college. -

97 STAT. 757 Public Law 98-115 98Th Congress an Act

PUBLIC LAW 98-115—OCT. 11, 1983 97 STAT. 757 Public Law 98-115 98th Congress An Act To authorize certain construction at military installations for fiscal year 1984, and for Oct. 11, 1983 other purposes. [H.R. 2972] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled. That this Act may Military be cited as the "Military Construction Authorization Act, 1984'\ Au'thorizSn Act, 1984. TITLE I—ARMY AUTHORIZED ARMY CONSTRUCTION AND LAND ACQUISITION PROJECTS SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army may acquire real property and may carry out military construction projects in the amounts shown for each of the following installations and locations: INSIDE THE UNITED STATES UNITED STATES ARMY FORCES COMMAND Fort Bragg, North Carolina, $31,100,000. Fort Campbell, Kentucky, $15,300,000. Fort Carson, Colorado, $17,760,000. Fort Devens, Massachusetts, $3,000,000. Fort Douglas, Utah, $910,000. Fort Drum, New York, $1,500,000. Fort Hood, Texas, $76,050,000. Fort Hunter Liggett, California, $1,000,000. Fort Irwin, California, $34,850,000. Fort Lewis, Washington, $35,310,000. Fort Meade, Maryland, $5,150,000. Fort Ord, California, $6,150,000. Fort Polk, Louisiana, $16,180,000. Fort Richardson, Alaska, $940,000. Fort Riley, Kansas, $76,600,000. Fort Stewart, Georgia, $29,720,000. Presidio of Monterey, California, $1,300,000. UNITED STATES ARMY WESTERN COMMAND Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, $31,900,000. UNITED STATES ARMY TRAINING AND DOCTRINE COMMAND Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, $1,500,000. Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, $5,900,000. -

Congressional Record—Senate S336

S336 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE January 28, 2010 This extraordinary woman educated ployed to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, as the sionalism with which he has carried herself on VA policy in order to provide chief of air operations, U.S. Central them out reflect a keen intellect and the best assistance to these men and Command Forward from 1991 to 1993. an unrivaled grasp of national security women and went so far as to accom- In 1993, now-Lieutenant Colonel Car- policies developed through both per- pany many of them to the VA to ensure lisle returned to the F–15 Eagle, as op- sonal experience and academic instruc- that they were served as thoroughly as erations officer of the 19th Fighter tion. General Carlisle earned a mas- possible. However, she knew that this Squadron and then commander of the ter’s degree in business administration wasn’t enough for her and that she 54th Fighter Squadron at Elmendorf from Golden Gate University in San could serve these veterans even more. Air Force Base, AK. Following com- Francisco, attended the National Secu- Ricki arranged for speakers from the mand, Lieutenant Colonel Carlisle at- rity Management Course at Syracuse VA, American Legion, Disabled Amer- tended Army War College in 1996, was University, the Seminar XXI—Inter- ican Veterans, State of Nevada, and selected for promotion to colonel, and national Relations programs at Massa- others to address the members of the returned to the Pacific in the F–15 chusetts Institute of Technology, and Siena Veterans Club. Ricki knew that Eagle as the Deputy Commander, 18th the Executive Course on National and she would not rest until she had served Operations Group at Kadena Air Base, International Security at George the needs of these veterans, and serve Japan. -

Catalog of Federal Metrology and Calibration Capabilities

NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION 546 Q 1 979 Edition U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/National Bureau of Standards National Bureau "of Standards Library, E-01 Admin. Bidg. Catalog o Federal Metrology and Calibration Capabilities NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is performed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government Agencies; develops,