United States Air Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 Be It Enacted Hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the ^^"'^'/Or^ C ^ United States Of

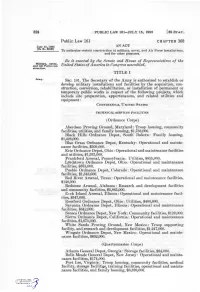

324 PUBLIC LAW 161-JULY 15, 1955 [69 STAT. Public Law 161 CHAPTER 368 July 15.1955 AN ACT THa R 68291 *• * To authorize certain construction at inilitai-y, naval, and Air F<n"ce installations, and for otlier purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the an^^"'^'/ord Air Forc^e conc^> United States of America in Congress assembled^ struction TITLE I ^'"^" SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army is authorized to establish or develop military installations and facilities by the acquisition, con struction, conversion, rehabilitation, or installation of permanent or temporary public works in respect of the following projects, which include site preparation, appurtenances, and related utilities and equipment: CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES TECHNICAL SERVICES FACILITIES (Ordnance Corps) Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Troop housing, community facilities, utilities, and family housing, $1,736,000. Black Hills Ordnance Depot, South Dakota: Family housing, $1,428,000. Blue Grass Ordnance Depot, Kentucky: Operational and mainte nance facilities, $509,000. Erie Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities and utilities, $1,933,000. Frankford Arsenal, Pennsylvania: Utilities, $855,000. LOrdstown Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Operational and maintenance facilities, $875,000. Pueblo Ordnance Depot, (^olorado: Operational and maintenance facilities, $1,843,000. Ked River Arsenal, Texas: Operational and maintenance facilities, $140,000. Redstone Arsenal, Alabama: Research and development facilities and community facilities, $2,865,000. E(.>ck Island Arsenal, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facil ities, $347,000. Rossford Ordnance Depot, Ohio: Utilities, $400,000. Savanna Ordnance Depot, Illinois: Operational and maintenance facilities, $342,000. Seneca Ordnance Depot, New York: Community facilities, $129,000. -

Jeannie Leavitt, MWAOHI Interview Transcript

MILITARY WOMEN AVIATORS ORAL HISTORY INITIATIVE Interview No. 14 Transcript Interviewee: Major General Jeannie Leavitt, United States Air Force Date: September 19, 2019 By: Lieutenant Colonel Monica Smith, USAF, Retired Place: National Air and Space Museum South Conference Room 901 D Street SW, Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20024 SMITH: I’m Monica Smith at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Today is September 19, 2019, and I have the pleasure of speaking with Major General Jeannie Leavitt, United States Air Force. This interview is being taped as part of the Military Women Aviators Oral History Initiative. It will be archived at the Smithsonian Institution. Welcome, General Leavitt. LEAVITT: Thank you. SMITH: So let’s start by me congratulating you on your recent second star. LEAVITT: Thank you very much. SMITH: You’re welcome. You’re welcome. So you just pinned that [star] on this month. Is that right? LEAVITT: That’s correct, effective 2 September. SMITH: Great. Great. So that’s fantastic, and we’ll get to your promotions and your career later. I just have some boilerplate questions. First, let’s just start with your full name and your occupation. LEAVITT: Okay. Jeannie Marie Leavitt, and I am the Commander of Air Force Recruiting Service. SMITH: Fantastic. So when did you first enter the Air Force? LEAVITT: I was commissioned December 1990, and came on active duty January 1992. SMITH: Okay. And approximately how many total flight hours do you have? LEAVITT: Counting trainers, a little over 3,000. SMITH: And let’s list, for the record, all of the aircraft that you have piloted. -

Gen. Mark A. Welsh III Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. Mark A. Welsh III Is Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, Washingto

Gen. Mark A. Welsh III Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. Mark A. Welsh III is Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, Washington, D.C. As Chief, he serves as the senior uniformed Air Force officer responsible for the organization, training and equipping of 690,000 active-duty, Guard, Reserve and civilian forces serving in the United States and overseas. As a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the general and other service chiefs function as military advisers to the Secretary of Defense, National Security Council and the President. General Welsh was born in San Antonio, Texas. He entered the Air Force in June 1976 as a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy. He has been assigned to numerous operational, command and staff positions. Prior to his current position, he was Commander, U.S. Air Forces in Europe. EDUCATION 1976 Bachelor of Science degree, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colo. 1984 Squadron Officer School, by correspondence 1986 Air Command and Staff College, by correspondence 1987 Master of Science degree in computer resource management, Webster University 1988 Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kan. 1990 Air War College, by correspondence 1993 National War College, Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C. 1995 Fellow, Seminar XXI, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge 1998 Fellow, National Security Studies Program, Syracuse University and John Hopkins University, Syracuse, N.Y. 1999 Fellow, Ukrainian Security Studies, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. 2002 The General Manager Program, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. -

Meet Tomorrow's Military Aviators We're Proud to Highlight These Daedalian Matching Scholarship Recipients Who Are Pursuing Careers As Military Aviators

Daedalian Quick Links Website | Membership Application | Scholarship Application | Make a Donation | Pay Dues | Magazine AUGUST 2018 Meet tomorrow's military aviators We're proud to highlight these Daedalian Matching Scholarship recipients who are pursuing careers as military aviators. They are our legacy! If you would like to offer career advice or words of encouragement to these future aviators, please email us at [email protected] and we'll pass them on to the cadets. Cadet Jeffrey Iraheta Colorado State University $1,850 scholarship Mile High Flight 18 "I am hoping to become a first generation pilot and military member in my family. Currently I have been accepted to attend pilot training as of February 2018 when I commission in May 2019. I hope to make a career in the Air Force and go over 20 years of active duty time in order to give back to this country." Cadet Corum Krebsbach University of Central Florida $7,250 scholarship George "Bud" Day Flight 61 "My career goals are to join the United States Air Force as an officer through ROTC and go through flight school to become a fighter pilot, or any other kind of pilot if I cannot become a fighter pilot. I wish to be a pilot in the Air Force as long as I possibly can. After retirement, I plan to work either as a civilian contractor for the Air Force through Boeing or Lockheed-Martin or another aerospace company, or possibly work for NASA." Cadet Sierra Legendre University of West Florida $7,250 scholarship George "Bud" Day Flight 61 "My goal is to be a career pilot in the United States Air Force. -

Southern Arizona Military Assets a $5.4 Billion Status Report Pg:12

Summer 2014 TucsonChamber.org WHAT’S INSIDE: Higher State Standards Southern Arizona Military Assets 2nd Session/51st Legislature Improve Southern Arizona’s A $5.4 Billion Status Report pg:12 / Report Card pg:22 / Economic Outlook pg:29 B:9.25” T:8.75” S:8.25” WHETHER YOU’RE AT THE OFFICE OR ON THE GO, COX BUSINESS KEEPS YOUR B:11.75” S:10.75” BUSINESS RUNNING. T:11.25” In today’s world, your business counts on the reliability of technology more than ever. Cox Business provides the communication tools you need for your company to make sure your primary focus is on what it should be—your business and your customers. Switch with confidence knowing that Cox Business is backed by our 24/7 dedicated, local customer support and a 30-day Money-Back Guarantee. BUSINESS INTERNET 10 /mo* AND VOICE $ • Internet speeds up to 10 Mbps ~ ~ • 5 Security Suite licenses and 5 GB of 99 Online Backup FREE PRO INSTALL WITH • Unlimited nationwide long distance A 3-YEAR AGREEMENT* IT’S TIME TO GET DOWN TO BUSINESS. CALL 520-207-9576 OR VISIT COXBUSINESS.COM *Offer ends 8/31/14. Available to new customers of Cox Business VoiceManager℠ Office service and Cox Business Internet℠ 10 (max. 10/2 Mbps). Prices based on 1-year service term. Equipment may be required. Prices exclude equipment, installation, taxes, and fees, unless indicated. Phone modem provided by Cox, requires electricity, and has battery backup. Access to E911 may not be available during extended power outage. Speeds not guaranteed; actual speeds vary. -

General James V. Hartinger

GENERAL JAMES V. HARTINGER Retired July 31, 1984. Died Oct. 9, 2000. General James V. Hartinger is commander of the U.S. Air Force Space Command and commander in chief of the North American Aerospace Defense Command, with consolidated headquarters at Peterson Air Force Base, Colo. General Hartinger was born in 1925, in Middleport, Ohio, where he graduated from high school in 1943. He received a bachelor of science degree from the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, N.Y., in 1949, and a master's degree in business administration from The George Washington University, Washington, D.C., in 1963. The general is also a graduate of Squadron Officer School at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., in 1955 and the Industrial College of the Armed Forces at Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C., in 1966. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in July 1943 and attained the grade of sergeant while serving in the Infantry. Following World War II he entered the academy and upon graduation in 1949 was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force. General Hartinger attended pilot training at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas, and Williams Air Force Base, Ariz., where he graduated in August 1950. He then was assigned as a jet fighter pilot with the 36th Fighter-Bomber Wing at Furstenfeldbruck Air Base, Germany. In December 1952 the general joined the 474th Fighter-Bomber Wing at Kunsan Air Base, South Korea. While there he flew his first combat missions in F-84 Thunderjets. Returning to Williams Air Force Base in July 1953, he served as a gunnery instructor with the 3526th Pilot Training Squadron. -

Brigadier General Randall K. "Randy" Bigum

BRIGADIER GENERAL RANDALL K. "RANDY" BIGUM BRIGADIER GENERAL RANDALL K. "RANDY" BIGUM Retired Oct. 1, 2001. Brig. Gen. Randall K. "Randy" Bigum is director of requirements, Headquarters Air Combat Command, Langley Air Force Base, Va. As director, he is responsible for all functions relating to the acquisition of weapons systems for the combat air forces, to include new systems and modifications to existing systems. He manages the definition of operational requirements, the translation of requirements to systems capabilities and the subsequent operational evaluation of the new or modified systems. He also chairs the Combat Air Forces Requirements Oversight Council for modernization investment planning. He directs a staff of seven divisions, three special management offices and three operating locations, and he actively represents the warfighter in defining future requirements while supporting the acquisition of today's combat systems. The general was born in Lubbock, Texas. A graduate of Ohio State University, Columbus, with a bachelor of science degree in business, he entered the Air Force in 1973. He served as commander of the 53rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Bitburg Air Base, Germany, the 18th Operations Group at Kadena Air Base, Japan, and the 4th Fighter Wing at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, S.C. He has served at Headquarters Tactical Air Command and the Pentagon, and at U.S. European Command in Stuttgart- Vaihingen where he was executive officer to the deputy commander in chief. The general is a command pilot with more than 3,000 flight hours in fighter aircraft. He flew more than 320 combat hours in the F- 15C during Operation Desert Storm. -

Historical Brief Installations and Usaaf Combat Units In

HISTORICAL BRIEF INSTALLATIONS AND USAAF COMBAT UNITS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM 1942 - 1945 REVISED AND EXPANDED EDITION OFFICE OF HISTORY HEADQUARTERS THIRD AIR FORCE UNITED STATES AIR FORCES IN EUROPE OCTOBER 1980 REPRINTED: FEBRUARY 1985 FORE~ORD to the 1967 Edition Between June 1942 ~nd Oecemhcr 1945, 165 installations in the United Kingdom were used by combat units of the United States Army Air I"orce~. ;\ tota) of three numbered .,lr forl'es, ninc comllklnds, frJur ;jfr divi'iions, )} w1.l\~H, Illi j(r,IUpl', <lnd 449 squadron!'! were at onE' time or another stationed in ',r'!;rt r.rftaIn. Mnny of tlal~ airrll'lds hnvc been returned to fann land, others havl' houses st.lnding wh~rr:: t'lying Fortr~ss~s and 1.lbcratorR nllce were prepared for their mis.'ilons over the Continent, Only;l few rcm:l.1n ;IS <Jpcr.Jt 11)11., 1 ;'\frfll'ldH. This study has been initl;ltcd by the Third Air Force Historical Division to meet a continuin~ need for accurate information on the location of these bases and the units which they served. During the pas t several years, requests for such information from authors, news media (press and TV), and private individuals has increased. A second study coverin~ t~e bases and units in the United Kingdom from 1948 to the present is programmed. Sources for this compilation included the records on file in the Third Air Force historical archives: Maurer, Maurer, Combat Units of World War II, United States Government Printing Office, 1960 (which also has a brief history of each unit listed); and a British map, "Security Released Airfields 1n the United Kingdom, December 1944" showing the locations of Royal Air Force airfields as of December 1944. -

Transfer of Training with Formation Flight Trainer. INSTITUTION Air Force Human Resources Lab.; Williams AFB, Ariz

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 109 451 CE 004 301 AUTHOR Reid, Gary B.; Cyrus, Michael L. TITLE Transfer of Training with Formation Flight Trainer. INSTITUTION Air Force Human Resources Lab.; Williams AFB, Ariz. Flying Training Div. REPORT NO AFHRL-TP-74-102 PUB DATE Dec 74 NOTE 15p. EDRS PPICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aircraft Pilots; *Flight Training; *Simulation; *Skill Development; Training Techniques; *Transfer of Training ABSTRACT The.present research was conducted to determine transfer of practice from a formation simulator to actual aircraft flight for the wing aircraft component of the formation flying task. Evidence in support of positive transfer was obtained by comparing students trained in the formation simulator with students who were essentially untrained and with students trained in the aircraft. This design provided dat'S for a direct comparison of five simulator sorties with two aircraft sorties in an effort to quickly establish a training cost/transfer comparison. The results indicate that the simulator has at least the training effectiveness of two aircraft sorties. (Author/JB) AFHRL-TR-74-102 AIR FORCE TRANSFER OF TRAINING WITH FORMATION FLIGHT TRAINER HUMAN By Gary B. Reid Michael L. Cyrus FLYING TRAINING DIVISION Williams Air Force Base, Arizona 85224 . RESOURCESDecember 1974 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. LABORATORY AIR FORCE SYSTEMS COMMAND BROOKS AIR FORCE BASE,TEXAS 78235 NOTICE When US Government drawing, specifications, or other data are used for oany purpose other than a definitely related Government procurement operation, the Government thereby incurs no responsibility .nor any obligation whatsoever, and the fact that the Government may have formulated, furnished, or in any way supplied the said drawings, specifications, or other data is no to be regarded by implication or otherwise, as in any manner licensing the holder or any other person or corporation, or conveying any rights or permission to manufacture, use, or sell any patented invention that may in any way be related thereto. -

Air Force Task Force to Assess Religious Climate

Vol. 45 No. 18 May 6, 2005 Inside COMMENTARY: Air Force’s religious respect history, Page 2 NEWS: Outstanding Academy educators, Page 3 Cadet rocket launch, Page 5 Tuskegee Airmen honored, Page 6 FEATURE: Aeronautics takes on C-130, Page 8 Medical group in Ecuador, Page 10 SPORTS: Men’s tennis results, Page 11 Ultimate frisbee, Page 11 Cycling, volleyball, Page 12 NEWS FEATURE: Music soothes, Page 13 Medical mission Maj. (Dr.) Dayton Kobayashi performs a physical exam on a pediatric patient while deployed to Ecuador for a medical Briefly readiness training exercise April 2-15. See complete coverage, Page 10. Academy Spring Clean-Up Air Force task force to assess religious climate May 20-22 all 10th Air Base Wing, Dean of the By Air Force Public Affairs Using feedback from that team, focus Separation of Church and State are being Faculty, 34th Training Wing, groups and others, the Academy leadership, taken very seriously by the Air Force. This Preparatory School, Tenants, WASHINGTON — Acting Secretary of with assistance from the Air Force chief of newly appointed task force will assess the reli- Facility Managers and Military the Air Force, the Honorable Michael L. chaplains, instituted a new training program gious climate and adequacy of Air Force Family Housing occupants and Dominguez, on Tuesday directed the Air for all Academy cadets, staff and faculty efforts to address the issue at the Academy. personnel will participate in Force Deputy Chief of Staff and Personnel, called Respecting the Spiritual Values of all Specifically, the task force is directed to clean-up efforts at the Lt. -

Before, During and After Sandy Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts Pages 8-13

AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 21 • Number 1 • Winter 2013 Before, During and After Sandy Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts Pages 8-13 In Review: 44th Annual A/TA Convention and the 2012 AMC and A/TA Air Mobility Symposium & Technology Exposition Pages 16-17 CONTENTS… Association News Chairman’s Comments ........................................................................2 President’s Message ...............................................................................3 Secretary’s Notes ...................................................................................3 Association Round-Up ..........................................................................4 AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 21 • Number 1 • Winter 2013 Cover Story Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published four times a year by the Airlift/Tanker Association, Before, During and After Sandy 9312 Convento Terrace, Fairfax, Virginia 22031. Postage paid at Belleville, Illinois. Air Mobility Forces Support Superstorm Sandy Relief Efforts ...8-13 Subscription rate: $40.00 per year. Change of address requires four weeks notice. The Airlift/Tanker Association is a non-profit Features professional organization dedicated to providing a forum for people interested in improving the capability of U.S. air mobility forces. Membership CHANGES AT THE TOP in the Airlift/Tanker Association is $40 annually or $110 for three years. Full-time student Air Mobility Command and membership is $15 per year. Life membership is 18th Air Force Get New Commanders ..........................................6-7 $500. Industry Partner membership includes five individual memberships and is $1500 per year. Membership dues include a subscription to Airlift/ An Interview with Lt Gen Darren McDew, 18AF/CC ...............14-15 Tanker Quarterly, and are subject to change. by Colonel Greg Cook, USAF (Ret) Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published for the use of subscribers, officers, advisors and members of the Airlift/Tanker Association. -

Fall 2015, Vol

Fall 2015, Vol. LVI No.3 CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 04 06 Newsbeat Daedalian Citation of Honor 05 09 Commander’s Perspective The WASP Uniforms 06 15 Adjutant’s Column Experiences of being among the first fifty 07 female pilots in the modern Air Force Linda Martin Phillips Book Reviews 08 34 Jackie Cochran Caitlin’s Corner 35 10 Chuck Yeager Awards Jack Oliver 18 Flightline America’s Premier Fraternal Order of Military Pilots 36 Promoting Leadership in Air and Space New/Rejoining Daedalians 37 Eagle Wing/Reunions 38 In Memoriam 39 Flight Addresses THE ORDER OF DAEDALIANS was organized on 26 March 1934 by a representative group of American World War I pilots to perpetuate the spirit of patriotism, the love of country, and the high ideals of sacrifice which place service to nation above personal safety or position. The Order is dedicated to: insuring that America will always be preeminent in air and space—the encourage- ment of flight safety—fostering an esprit de corps in the military air forces—promoting the adoption of military service as a career—and aiding deserving young individuals in specialized higher education through the establishment of scholarships. THE DAEDALIAN FOUNDATION was incorporated in 1959 as a non-profit organization to carry on activities in furtherance of the ideals and purposes of the Order. The Foundation publishes the Daedalus Flyer and sponsors the Daedalian Scholarship Program. The Foundation is a GuideStar Exchange member. The Scholarship Program recognizes scholars who indicate a desire to become military pilots and pursue a career in the military. Other scholarships are presented to younger individuals interested in aviation but not enrolled in college.