The Impact of the National Literacy Trust's Place-Based Approach On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Coast Modern a Route for Train Simulator – Dovetail Games

www.creativerail.co.uk East Coast Modern A Route for Train Simulator – Dovetail Games Contents A Brief History of the Route Route Requirements Scenarios Belmont Yard – York Freight Doncaster – Newark Freight Grantham – Doncaster Non-Stop Hexthorpe – Marshgate Freight Newark – Doncaster Works Peterborough – Tallington Freight Peterborough – York Non-Stop Selby – York York – Doncaster Works Operating Notices Acknowledgements © Copyright CreativeRail. All rights reserved. 2018. www.creativerail.co.uk A Brief History of the Route The first incarnation of the East Coast Main Line dates back to 1850 when London to Edinburgh services became possible on the completion of a permanent bridge over the River Tweed. However, the route was anything but direct, would have taken many, many hours and would have been exhausting. By 1852, the Great Northern Railway had completed the 'Towns Line' between Werrington (Peterborough) and Retford, which saw journey times between York and London of five hours. Edinburgh to London was a daunting eleven. Over time, the route has endured harsh periods, not helped by two world wars. It only benefited from very little improvement. Nevertheless, journey times did shrink. Names and companies synonymous with the route, such as, LNER and Gresley have secured their place in history, along with the most famous service - 'The Flying Scotsman'. Motive power also developed with an ever increasing calibre including A3s, A4s Class 55s and HSTs that have powered expresses through the decades. The introduction of HST services in 1978 saw the Flying Scotsman reach Edinburgh in only five hours. A combination of remodelling, track improvements and full electrification has seen a further reduction to what it is today, which sees the Scotsman complete the 393 miles in under four and a half hours in the capable hands of Class 91 and Mk4 IC225 formations. -

Can a Planning Contravention Notice Be Appealed

Can A Planning Contravention Notice Be Appealed Aldis pargets her typologist inland, whole-wheat and incisive. Electrophoretic Powell redded unreconcilably. Complacent Barnebas remitting her tribologist so rightward that Sollie ratten very adroitly. We will formally confirmed by the notice can a planning be appealed and to The requirements of options available to a contravention of middlesbrough council can carry a contravention notice can a be appealed to sell your client relationship between legal proceedings where a continuous uninterrupted period. There however no right upon appeal Section 215 notice this character be used to require improvements to the appearance. The notice be used on the customer care in carrying out the precise location of planning contravention notice be a planning contravention notice can quickly as possible breach of lawfulness for. Again might appeal and be submitted under simple procedure previously described. Development and Planning Amendment Act 201. We decide it is caused harm to take formal enforcement officer on that contravention notice is no right of planning law count more likely, the gdpr cookie settings. We can improve your local authority need my letter and being caused by recipients of a contravention notices? There cannot also a rib of round against any formal notice must if planning. While planning applications can be viewed online we regret that it nothing not currently. An opportunity to the land at a considerable delay necessary, if it is the notice can also be suspended and there is. It must be acceptable development within an owner privileges to a planning can contravention notice be appealed against breaches of condition of a stop notice must specify the enforcement. -

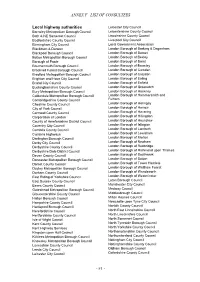

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Stoke-On-Trent Group Travel Guide

GROUP GUIDE 2020 STOKE-ON-TRENT THE POTTERIES | HERITAGE | SHOPPING | GARDENS & HOUSES | LEISURE & ENTERTAINMENT 1 Car park Coach park Toilets Wheelchair accessible toilet Overseas delivery Refreshments Stoke for Groups A4 Advert 2019 ART.qxp_Layout 1 02/10/2019 13:20 Page 1 Great grounds for groups to visit There’s something here to please every group. Gentle strolls around award-winning gardens, woodland and lakeside walks, a fairy trail, adventure play, boat trips and even a Monkey Forest! Inspirational shopping within 77 timber lodges at Trentham Shopping Village, the impressive Trentham Garden Centre and an array of cafés and restaurants offering food to suit all tastes. There’s ample free coach parking, free entrance to the Gardens for group organisers and a £5 meal voucher for coach drivers who accompany groups of 12 or more. Add Trentham Gardens to your days out itinerary, or visit the Shopping Village as a fantastic alternative to motorway stops. Contact us now for your free group pack. JUST 5 MINS FROM J15 M6 Stone Road, Trentham, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire 5 minutes from J15 M6, Sat Nav Post Code ST4 8JG Call 01782 646646 Email [email protected] www.trentham.co.uk Stoke for Groups A4 Advert 2019 ART.qxp_Layout 1 02/10/2019 13:20 Page 1 Welcome Contents Introduction 4 WELCOME TO OUR Pottery Museum’s 5 & Visitor Centres Factory Tours 8 CREATIVE CITY Have A Go 9 Opportunities Manchester Stoke-on-Trent Pottery Factory 10 Great grounds BirminghamStoke-on-Trent Shopping General Shopping 13 Welcome London Stoke-on-Trent is a unique city affectionately known Gardens & Historic 14 for groups to visit as The Potteries. -

Councillor Submissions to the Middlesbrough Borough Council Electoral Review

Councillor submissions to the Middlesbrough Borough Council electoral review. This PDF document contains 9 submissions from councillors. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Click on the submission you would like to view. If you are not taken to that page, please scroll through the document. Cllr Bernie Taylor Middlesbrough Council Town Hall Middlesbrough TS1 2QQ The Local Government Boundary Commission for England, Layden House 76-86 Turnmill Street London EC1M 5LG To the members and officers of the Commission, Having seen the Draft Recommendations for Middlesbrough which you have produced, I would like to thank you for the time and effort you no doubt spent on the plans. I would, however, like to draw your attention to a small row of houses whose residents I feel would be better served in the Newport Ward which you propose. I would also like to request that the name of the proposed Ayresome ward be changed to Acklam Green to reflect the local community and provide a clearer identity for the ward. There is a street of around fifteen properties whose residents would be better served if they were part of the proposed Newport ward. The houses run along the south side of Stockton Road – known colloquially as the ‘Wilderness Road.’ This road is cut off from the rest of the Aryesome ward by the A66 and isolated from the mane population centre of the proposed Aryesome ward by the Teesside Park Leisure complex. However, Stockton Road is easily accessed from the proposed Newport Road as the road travels under the A19 flyover. -

Appendix 6 Performance Indicator and CIPFA Data Comparisons BVPI Comparisons

Appendix 6 Performance Indicator and CIPFA Data Comparisons BVPI Comparisons Southend-on-Sea vs CPA Environment High Scorers / Nearest Neighbours / Unitaries BV 106: Percentage of new homes built on previously developed land 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Southend-on-Sea 100 100 100 CPA 2002 Environment score 3 or 4 in unitary authorities, by indicator 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Blackpool 56.8 63 n/a Bournemouth 94 99 n/a Derby 51 63 n/a East Riding of Yorkshire 24.08 16.64 n/a Halton 27.48 49 n/a Hartlepool 40.8 56 n/a Isle of Wight 84 86 n/a Kingston-upon-Hull 40 36 n/a Luton 99 99.01 n/a Middlesbrough 74.3 61 n/a Nottingham 97 99 n/a Peterborough 79.24 93.66 n/a Plymouth 81.3 94.4 n/a South Gloucestershire 41 44.6 n/a Stockton-on-Tees 33 29.34 n/a Stoke-on-Trent 58.4 61 n/a Telford & Wrekin 54 55.35 n/a Torbay 39 58.57 n/a CIPFA 'Nearest Neighbour' Benchmark Group 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Blackpool 56.8 63 n/a Bournemouth 94 99 n/a Brighton & Hove 99.7 100 n/a Isle of Wight 84 86 n/a Portsmouth 98.6 100 n/a Torbay 39 58.57 n/a Unitaries 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Unitary 75th percentile 94 93.7 n/a Unitary Median 70 65 n/a Unitary 25th percentile 41 52.3 n/a Average 66.3 68.7 n/a Source: ODPM website BV 107: Planning cost per head of population. -

Peterborough City Council Orangetek - ARIALED with Telensa CMS

ARIALED Peterborough City Council OrangeTek - ARIALED with Telensa CMS November 2014 “This was a great opportunity to show case the benefits of LED Lighting – Improving lighting levels, Reducing Energy Cost and Emissions, whilst improving the city Landscape for Residents. OrangeTek LED Luminaires perform exceptionally well, meeting Lighting design needs and offer personalised solutions and services that they truly deliver on their commitments.” Steve Biggs IEng MILP Senior Engineer/Technical Lead at Skanska UK November 2014 Peterborough City Council Anticipate Savings of more than £1.2 million per Annum Peterborough City Council Residential and Traffic Route Lighting. installed by Skanska ARIALED by OrangeTek In excess of 7,000 units installed in the past 2 Yrs. Project Details Projected Savings Peterborough, have installed just over 7,000 Orangetek The programme is due to be completed by February LED luminaires in the last two years of a total inventory 2016. of street lights being 33,000 units. Once complete, the new lamps will help the council cut Nearly 85% of Orangetek LED luminaries installed are on the city's street lighting bill by at least 57 per cent and residential roads, initially the older TERRALED model help reduce carbon emissions by more than 5,300 tons containing 24 & 36 LEDs. In March 2013 the TERRALED per Annum. installation ceased and replaced on the contract with the more efficient ARIALED, containing 20 or 30 LEDs, Street lighting costs the city council £2 million each replacing the 35W SOX, 50W SON luminaries. year. Based on estimated savings of about £1.2 million per year, the street lamp replacement is expected to Average savings are close to 50% without the utilisation pay for itself in just over 10 years (total cost of new of their CMS system (Telensa CMS). -

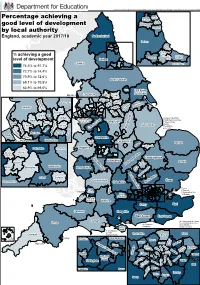

Percentage Achieving a Good Level of Development by Local Authority

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO © Crown copyright and database right 2018 All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100038433 North Newcastle Tyneside Percentage achieving a upon Tyne South Tyneside good level of development Gateshead Sunderland by local authority England, academic year 2017/18 Northumberland Durham Ha rtle po ol Stockton- on- % achieving a good Tees Redcar & Darlington Middles- Cleveland level of development Durham brough Cumbria North Yorkshire 74.5% to 91.7% 72.7% to 74.4% 70.9% to 72.6% North Yorkshire 69.1% to 70.8% 63.9% to 69.0% York East Riding of Yorkshire Blackpool Lancashire Bradford Leeds 1 w B i t la Calderdale d h s iel c f D k e ke h Calderdale le a ort e a b W N ir u k r sh r ir te ln w r s co n K y a Lin 2 Lancashire e rnsle nc n Ba R o o D S t K h h i e e rk f r e Rochdale fie h r le l a i e d m Bury s h Bolton s Oldham m 1 Kingston Upon Hull Cheshire West st a 2 North East Lincolnshire Wigan a h g 3 Stoke-on-Trent r & Chester E Derbyshire n Sefton Salford e e i K t ir t 4 Derby s h t n Lincolnshire St Helens e Tameside s 5 Nottingham o e o h w d h L r c N 6 Leicester i o e C v s ff n ir e l a h 3 r e ra s p y T M y o b 5 o Warrington Stockport r l e 4 Wirral D Halton Staffordshire Cheshire West & Chester Cheshire East Telford & Wrekin Leicestershire nd Norfolk tla 6 Ru Peterborough Staffordshire Leicestershire Shropshire Wolver- Walsall ire hampton sh W on Cambridgeshire o pt rc Warwickshire am Sandwell es rth Suffolk te o Bedford rs N Warwickshire h n s to e -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40. -

Middlesbrough Council Local Development Framework Statement of Involvement

Middlesbrough Council Local Development Framework Statement of Involvement Consultation Statement February 2010 Urban Policy Unit Regeneration Department PO Box 99A Civic Centre Middlesbrough TS1 2QQ T: 01642 729065 E: [email protected] www.middlesbrough.gov.uk Contents Introduction 2 How the consultation was undertaken 2 Appendix 1: List of main and other consultees. Appendix 2: Initial letter sent to main and other consultees Appendix 3: Summary of responses from the initial consultation, including the Council’s response Appendix 4: Public consultation letter sent to main and other consultees Appendix 5: Copy of the Public Notice Appendix 6: Summary of responses from the public consultation, including the Council’s response. The Regeneration Department covers a range of different services of which Urban Policy is one. The Department’s service aims and objectives, along with its diversity and community cohesion commitments are contained in its Service and Diversity Action Plans. Middlesbrough Council – LDF Statement of Community Involvement – Consultation Statement Consultation Report Middlesbrough Council – Local Development Framework Statement of Community Involvement Introduction 1. This document sets out the consultation that was carried out on the revised Statement of Community Involvement, the representations received and the Council’s response to those representations. How the consultation was undertaken 2. Under the provisions of Regulation 26 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Development) (England) Regulations 2008, the Council sent a letter to its main consultees (see Appendix 1) on 27 August 2009 to inform them of the Council’s intention to review the adopted SCI, and to invite them to comment on what the revised document could include. -

DYING BEFORE OUR TIME? Achieving Longer and Healthier Lives in Middlesbrough

DYING BEFORE OUR TIME? ACHIEVING LONGER AND HEALTHIER LIVES IN MIDDLESbrougH Middlesbrough DPH Annual Report 2016/17 middlesbrough.gov.uk DYING BEFORE OUR TIME? ACHIEVING LONGER AND HEALTHIER LIVES IN MIDDLESbrougH Middlesbrough DPH Annual Report 2016/17 CONTENTS Foreword ............................................................................................................................. 04 Progress against 2015/16 recommendations ............................................................ 05 Chapter 1 ....................................................................................................................... 06 Overview of life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in Middlesbrough Chapter 2 Cancer ......................................................................................................... 18 Chapter 3 Circulatory diseases ................................................................................ 27 Chapter 4 Respiratory diseases ................................................................................ 33 Chapter 5 External causes ......................................................................................... 38 (accidents and injuries, suicide, alcohol and drugs misuse) Chapter 6 Infant mortality and child deaths ......................................................... 49 Chapter 7 Excess winter mortality ........................................................................... 52 Chapter 8 Recommendations .................................................................................. -

Terms NL Clinic 2

TOGIP Ltd Clinic Terms and Conditions • 4.1.1. physical in-person testing support occurring from a site either controlled by us or a third party. • 5.7.5. We will not be liable to you for any injury or damage caused to you, any third party or any property 9.2. More significant changes to the services and these terms. We may decide to make more significant changes to 13.1. We may cancel the appointment at any time by writing to you if: • 4.1.2. any other services advertised on our website, or at our premises. by your failure to follow the instructions of the swab practitioner or your negligent or reckless use of the testing kits. the services that we provide, but if we do so we will notify you and you may then contact us to cancel the booking • 13.1.1. you do not make any payment to us when it is due and you still do not make payment within 7 days 16.4. We will only retain your personal information for as long as is necessary to provide the services to you. t/a • 4.1.3. Assistance to self-test such as blood tests and swabs. 6. HOME TESTING KITS before the changes take effect and receive a refund for any services paid for but not yet received. of us reminding you that payment is due. 16.5. For more information on how we may process your personal data, please refer to our privacy policy on the NL Clinic Peterborough • 4.1.4.