The Problems of Our Musical Folklore*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euroradio Folk Festival RÄTTVIK 28–30 JUNI

P2 sveriges radio presenterar Euroradio folk festival RÄTTVIK 28–30 JUNI 2014 AN ILJ S ID V IK S U M V A L E 29 JUNI – 5 JULI D LEKSAND • MORA SID 1 Euroradio folk festival N MED RESERVATION FÖR& ÄNDRINGAR RÄTTVIK E FOTO: MICKE GRÖNBERG/ SVERIGES RADIO Welcome! The Swedish Radio is both proud and happy to be able to present a part of Sweden which is famous for its blue hills, its flowery mead- ows, its magical lakes and its music. Folk musicians in the beautiful national cos- tumes of the province of Dalecarlia are a common feature at Swedish weddings, re- Välkommen! gardless of where in the country the wedding Vi från Sveriges Radio är stolta och glada över takes place, and when Swedes celebrate att få visa upp en del av Sverige som är känt midsummer and erect a maypole decorated för sina blåa kullar, sina blommande ängar, with summer flowers and green birch leaves, sina trollska sjöar och sin musik. nowhere in Sweden are people more eager to dance round the maypole to the accom- Spelmän i vackra folkdräkter från Dalarna paniment of accordion and fiddles than in är ett vanligt inslag på svenska bröllop oav- Dalecarlia. sett var i landet bröllopet står och att resa en midsommarstång klädd med sommarens Never before have tradition and innovation blommor och gröna björkris som man dansar been as intimately linked as they are in the kring till dragspel och fiol gör man ingenstans folk music of today, and therefore we are es- så gärna som här. -

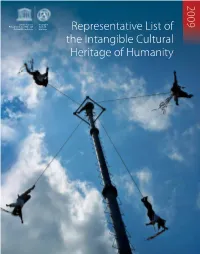

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

110 ICTM Bulletin (Apr 2007).Pdf

CONTENTS From the ICTMSecretariat 2 From The SecReTaRy General, .4 39Th World ConfeRence of the ICTM July 4 - 11,2007 - Vienna, AUStria ConfeRence UpdaTe 6 Preliminary Program 19 ICTM Election 2007 .49 ANNOUNCEMENTS 38th Ordinary Meeting of the ICTM GeneRal Assembly 50 9th Meeting of the ICTM ASSembly of National & Regional RepS 50 Study Group on Historical Sources of Traditional MuSic - Meeting 51 Study Group on Anthropology of MuSic in Mediterranean Cultures - Meeting 51 Ethnomusicology Symposium aTCardiffUniversity 52 Fourth Conference on Interdisciplinary Musicology - CIM 2008 52 REPORTS National and Regional Committees Denmark 55 Germany 56 Switzerland 58 Taiwan 59 Liaison Officers Vanuatu 60 Study GroupS Study Group on Ethnochoreology 60 Sub-Study Group Group on Dance Iconography 65 Study Group on MusicS of Oceania 66 SympoSium "Ethnomusicology and Ethnochoreology in Education: IsSues in Applied Scholarship' 67 RECENT PUBLICATIONS 70 ICTM MEETING CALENDAR 71 MEETINGS OF RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 74 MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION & APPLICATION 75 CONTENTS From the ICTMSecretariat 2 From The SecReTaRy General, .4 39Th World ConfeRence of the ICTM July 4 - 11,2007 - Vienna, AUStria ConfeRence UpdaTe 6 Preliminary Program 19 ICTM Election 2007 .49 ANNOUNCEMENTS 38th Ordinary Meeting of the ICTM GeneRal Assembly 50 9th Meeting of the ICTM ASSembly of National & Regional RepS 50 Study Group on Historical Sources of Traditional MuSic - Meeting 51 Study Group on Anthropology of MuSic in Mediterranean Cultures - Meeting 51 Ethnomusicology Symposium -

Documenting and Presenting Intangible Cultural Heritage on Film

DOCUMENTING AND PRESENTING INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE ON FILM DOCUMENTING AND PRESENTING INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE ON FILM DOKUMENTIRANJE IN PREDSTAVLJANJE NESNOVNE KULTURNE DEDIŠČINE S FILMOM Edited by Nadja Valentinčič Furlan Ljubljana, 2015 Documenting and Presenting Intangible Cultural Heritage on Film Editor: Nadja Valentinčič Furlan Peer-reviewers: Felicia Hughes-Freeland, Tanja Bukovčan Translation into English and language revision of English texts: David Limon Translation into Slovene: Franc Smrke, Nives Sulič Dular, Nadja Valentinčič Furlan Language revision of Slovene texts: Vilma Kavšček Graphic art and design: Ana Destovnik Cover photo: Confronting the “ugly one” in Drežnica, photomontage from photographs by Kosjenka Brajdić Petek (Rovinj, 2015) and Rado Urevc (Drežnica, 2007). Issued and published by: Slovene Ethnographic Museum, represented by Tanja Roženbergar Printed by: T2 studio d.o.o. Print run: 500 Ljubljana, 2015 © 2015, authors and the Slovene Ethnographic Museum The authors are responsible for the content of the contributions. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 719:791.229.2(497.4)(082) DOKUMENTIRANJE in predstavljanje nesnovne kulturne dediščine s filmom = Documenting and presenting intangible cultural heritage on film / uredila Nadja Valentinčič Furlan ; [prevodi David Limon ... et al.]. - Ljubljana : Slovenski etnografski muzej, 2015 ISBN 978-961-6388-60-3 1. Vzp. stv. nasl. 2. Valentinčič Furlan, Nadja 283065600 Published with the support of the Ministry of -

52. Međunarodna Smotra Folklora / 52Nd International Folklore Festival Zagreb, Croatia 2018

Zagreb, Croatia 2018. ND international folklore festival 52 nd INTERNATIONAL Baština i FOLKLORE FESTIVAL migracije 18.-22.7.2018. 52. Međunarodna ZAGREB, smotra folklora HRVATSKA www.msf.hr 52. međunarodna smotra folklora / 52 52. Međunarodna smotra folklora 52nd International Folklore Festival 18. - 22. 7. 2018. Zagreb, Hrvatska Baština i migracije U EUROPSKOJ GODINI KULTURNE BAŠTINE / IN EUROPEAN YEAR OF CULTURAL HERITAGE POD POKROVITELJSTVOM HRVATSKOG POVJERENSTVA ZA UNESCO I HRVATSKOGA SABORA / UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE CROATIAN COMMISSION FOR UNESCO AND CROATIAN PARLIAMENT Međunarodna smotra The International Folklore folklora u Zagrebu Festival Međunarodna smotra folklora održava The International Folklore Festival has se u Zagrebu od 1966. godine. Prikazuje i traditionally been held in Zagreb since afirmira tradicijsku kulturu i folklor brojnih 1966. The Festival’s objective is to present domaćih i stranih sudionika. Nastavlja dugu and affirm the status of traditional culture tradiciju smotri Seljačke sloge, kulturne, and folklore of its numerous local and prosvjetne i dobrotvorne organizacije international participants. The event Hrvatske seljačke stranke između dvaju continues the old tradition of festivals svjetskih ratova. U suvremenoj Hrvatskoj organised by the Peasant Concord, a cultural, Smotra je dio svjetskog pokreta za očuvanje educational and humanitarian organisation kulturne baštine koji prati programe of the Croatian Peasant Party from time in UNESCO-a. Odlukom Ministarstva kulture between the two World Wars. In modern-day Republike Hrvatske i Grada Zagreba, 2014. Croatia, the International Folklore Festival godine Smotra je proglašena festivalskom has become part of the global movement priredbom od nacionalnog značenja. led by the UNESCO that aims to safeguard intangible cultural heritage. In 2014, the Croatian Ministry of Culture and the City of Zagreb pronounced it as a festival of national significance. -

Imitation of Animal Sound Patterns in Serbian Folk Music

journal of interdisciplinary music studies fall 2011, volume 5, issue 2, art. #11050201, pp. 101-118 Imitation of animal sound patterns in Serbian folk music Milena Petrovic1 and Nenad Ljubinkovic2 1 Faculty of Music, University of Arts Belgrade 2 Institute of Literature Belgrade Background in evolution of music. Many parallels can be drawn between human music and animal sounds in traditional Serbian folk songs and dances. Animal sound patterns are incorporated into Serbian folk songs and dances by direct imitation for different ritual purposes. Popular dances are named after animals. Background in folkloristics. The hypothesized relationship between humans and other members of the animal kingdom is reflect in theories that consider imitation of animal sounds as an element from which human language developed. In Serbian folklore, a frequent trope is the eternal human aspiration to speak to animals and learn their language. Serbs maintain an animal cult, showing the importance of totem animals in everyday life and rituals. Aims. The main aim of the article is to highlight some of the similarities between humans' and animals' communication systems, and to discuss this in light of the possible origins of music and language. We aim to show that there is an unbreakable connection between humans and other animals, and that their mutual affection may be because humans and animals have, since antiquity, lived in a close contact. Humans imitated animals' sound patterns and incorporated them into their primordial songs and dances for ritual purposes. As traditional Serbian culture is particularly nature-oriented, we can still find many elements that reflect animal sound patterns in their music folklore. -

Eurostat – Culture Statistics 2019 Edition

Culture statistics 2019 edition STATISTICAL BOOKS Culture statistics 2019 edition Printed by Imprimerie Bietlot Manuscript completed in September 2019 Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 Theme: Population and social conditions Collection: Statistical books © European Union, 2019 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Copyright for photographs: cover: © toriru/Shutterstock.com; Chapter 1: © Dodokat/ Shutterstock.com; Chapter 2: © dmitro2009/Shutterstock.com; Chapter 3: © Stock-Asso/ Shutterstock.com; Chapter 4: © Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock.com; Chapter 5: © Elnur/Shutterstock. com; Chapter 6: © Kamira/Shutterstock.com; Chapter 7: © DisobeyArt/Shutterstock.com; Chapter 8: © Dusan Petkovic/Shutterstock.com; Chapter 9: © Anastasios71/Shutterstock.com. For any use or reproduction of material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. For more information, please consult: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/about/policies/copyright Print: ISBN 978-92-76-09703-7 PDF: ISBN 978-92-76-09702-0 doi:10.2785/824495 doi:10.2785/118217 Cat. No: KS-01-19-712-EN-C Cat. No: KS-01-19-712-EN-N Abstract Abstract This fourth edition of publication Culture statistics — 2019 edition presents a selection of indicators on culture pertaining to cultural employment, international trade in cultural goods, cultural enterprises, cultural participation and the use of the internet for cultural purposes, as well as household and government cultural expenditure. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, 2009; 2010

2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

ALMA – Austria Julia Lacherstorfer

ALMA – Austria Julia Lacherstorfer - violin, voice Evelyn Mair - violin, voice Matteo Haitzmann - violin, voice Marie-Theres Stickler – accordion, voice Marlene Lacherstorfer - double bass, voice The five-piece band ALMA, founded in 2011, has deep roots in Austrian folk tradition. Their music can be understood as a bow to tradition – full of reverence, yet with a twinkle in the eye. All the band members grew up in musical families, so singing and playing folk music was as much a part of daily life during their childhood as going to school or learning to ride a bicycle. Now they have grown up and they breathe new life into the old forms. ALMA arrange and compose their own pieces, aiming to create a vibrant, contemporary sound, playfully combining elements of traditional music in arrangements that are sometimes complex but always accessible. www.almamusik.at ALMA – Österrike Julia Lacherstorfer - violin, sång Evelyn Mair - violin, sång Matteo Haitzmann - violin, sång Marie-Theres Stickler – dragspel, sång Marlene Lacherstorfer - kontrabas, sång Femmannabandet ALMA, grundat 2011, har sina rötter djupt rotade i den österrikiska folkmusiken. Deras musik kan ses som en ärofull bugning till traditionen – men med glimten i ögat. Bandmedlemmarna växte upp i musikaliska familjer, att sjunga och spela folkmusik var i deras barndom lika naturligt som att gå till skolan eller lära sig att cykla. Som vuxna har de fortsatt att utveckla traditionen. ALMA arrangerar och komponerar sina egna låtar och vill skapa en livfull, modern klangvärld som lekfullt kombinerar traditionella element med ibland komplexa men alltid lättillgängliga arrangemang. 1 Andreas Aase – Norway Andreas Aase – guitar-bouzouki Andreas Aase spent many years as a sideman for Norway’s best-known artists. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (As of 2018)

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (As of 2018) 2018 Art of dry stone walling, knowledge and techniques Croatia – Cyprus – France – Greece – Italy – Slovenia – Spain – Switzerland As-Samer in Jordan Jordan Avalanche risk management Switzerland – Austria Blaudruck/Modrotisk/Kékfestés/Modrotlač, resist block printing Austria – Czechia – and indigo dyeing in Europe Germany – Hungary – Slovakia Bobbin lacemaking in Slovenia Slovenia Celebration in honor of the Budslaŭ icon of Our Lady (Budslaŭ Belarus fest) Chakan, embroidery art in the Republic of Tajikistan Tajikistan Chidaoba, wrestling in Georgia Georgia Dondang Sayang Malaysia Festivity of Las Parrandas in the centre of Cuba Cuba Heritage of Dede Qorqud/Korkyt Ata/Dede Korkut, epic Azerbaijan – culture, folk tales and music Kazakhstan – Turkey Horse and camel Ardhah Oman Hurling Ireland Khon, masked dance drama in Thailand Thailand La Romería (the pilgrimage): ritual cycle of 'La llevada' (the Mexico carrying) of the Virgin of Zapopan Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa, knowledge and China practices concerning life, health and illness prevention and treatment among the Tibetan people in China Međimurska popevka, a folksong from Međimurje Croatia Mooba dance of the Lenje ethnic group of Central Province of Zambia Zambia Mwinoghe, joyous dance Malawi Nativity scene (szopka) tradition in Krakow Poland Picking of iva grass on Ozren mountain Bosnia and Herzegovi na Pottery skills of the women of Sejnane Tunisia Raiho-shin, ritual visits of deities in masks -

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

4 COM ITH/09/4.COM/CONF.209/13 Rev.2 Paris, 23 September 2009 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION FOR THE SAFEGUARDING OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE INTERGOVERNMENTAL COMMITTEE FOR THE SAFEGUARDING OF THE INTANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE Fourth session Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 28 September to 2 October 2009 Item 13 of the Provisional Agenda: Evaluation of the nominations for inscription on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Summary At its third session, the Committee established a Subsidiary Body responsible for the examination of nominations for inscription on the Representative List in 2009 and 2010 (Decision 3.COM 11). This document constitutes the report of the Subsidiary Body, which includes an overview of the 2009 nomination files (Part A), the recommendations of the Subsidiary Body (Part B), and a set of draft decisions for the Committee’s consideration (Part C). Decision required: paragraph 25 ITH/09/4.COM/CONF.209/13 Rev.2 – page 2 Report and recommendations of the Subsidiary Body for the examination of nominations to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (Decision 4.COM 1.SUB 5) 1. According to paragraph 23 of the Operational Directives, the examination of nominations to the Representative List is accomplished by a Subsidiary Body of the Committee established in accordance with Rule 21 of its Rules of Procedure. At its third session (Istanbul, Turkey, 4 to 8 November 2008), the Committee established a Subsidiary Body responsible for the examination of nominations for inscription on the Representative List in 2009 and 2010 (Decision 3.COM 11).