Environmental Assessments of Swedish Cyprinids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Fish Edna Metabarcoding: Field Replicates Disproportionately Improve the Detection of Stream Associated Vertebrate Specie

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.26.437227; this version posted March 26, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 2 3 Beyond fish eDNA metabarcoding: Field replicates 4 disproportionately improve the detection of stream 5 associated vertebrate species 6 7 8 9 Till-Hendrik Macher1, Robin Schütz1, Jens Arle2, Arne J. Beermann1,3, Jan 10 Koschorreck2, Florian Leese1,3 11 12 13 1 University of Duisburg-Essen, Aquatic Ecosystem Research, Universitätsstr. 5, 45141 Essen, 14 Germany 15 2German Environmental Agency, Wörlitzer Platz 1, 06844 Dessau-Roßlau, Germany 16 3University of Duisburg-Essen, Centre for Water and Environmental Research (ZWU), Universitätsstr. 17 3, 45141 Essen, Germany 18 19 20 21 22 Keywords: birds, biomonitoring, bycatch, conservation, environmental DNA, mammals 23 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.26.437227; this version posted March 26, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 24 Abstract 25 Fast, reliable, and comprehensive biodiversity monitoring data are needed for 26 environmental decision making and management. Recent work on fish environmental 27 DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding shows that aquatic diversity can be captured fast, reliably, 28 and non-invasively at moderate costs. -

Labidesthes Sicculus

Version 2, 2015 United States Fish and Wildlife Service Lower Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office 1 Atherinidae Atherinidae Sand Smelt Distinguishing Features: — (Atherina boyeri) — Sand Smelt (Non-native) Old World Silversides Old World Silversides Old World (Atherina boyeri) Two widely separated dorsal fins Eye wider than Silver color snout length 39-49 lateral line scales 2 anal spines, 13-15.5 rays Rainbow Smelt (Non -Native) (Osmerus mordax) No dorsal spines Pale green dorsally Single dorsal with adipose fin Coloring: Silver Elongated, pointed snout No anal spines Size: Length: up to 145mm SL Pink/purple/blue iridescence on sides Distinguishing Features: Dorsal spines (total): 7-10 Brook Silverside (Native) 1 spine, 10-11 rays Dorsal soft rays (total): 8-16 (Labidesthes sicculus) 4 spines Anal spines: 2 Anal soft rays: 13-15.5 Eye diameter wider than snout length Habitat: Pelagic in lakes, slow or still waters Similar Species: Rainbow Smelt (Osmerus mordax), 75-80 lateral line scales Brook Silverside (Labidesthes sicculus) Elongated anal fin Images are not to scale 2 3 Centrarchidae Centrarchidae Redear Sunfish Distinguishing Features: (Lepomis microlophus) Redear Sunfish (Non-native) — — Sunfishes (Lepomis microlophus) Sunfishes Red on opercular flap No iridescent lines on cheek Long, pointed pectoral fins Bluegill (Native) Dark blotch at base (Lepomis macrochirus) of dorsal fin No red on opercular flap Coloring: Brownish-green to gray Blue-purple iridescence on cheek Bright red outer margin on opercular flap -

Beyond Fish Edna Metabarcoding: Field Replicates Disproportionately Improve the Detection of Stream Associated Vertebrate Species

Metabarcoding and Metagenomics 5: 59–71 DOI 10.3897/mbmg.5.66557 Research Article Beyond fish eDNA metabarcoding: Field replicates disproportionately improve the detection of stream associated vertebrate species Till-Hendrik Macher1, Robin Schütz1, Jens Arle2, Arne J. Beermann1,3, Jan Koschorreck2, Florian Leese1,3 1 University of Duisburg-Essen, Aquatic Ecosystem Research, Universitätsstr. 5, 45141 Essen, Germany 2 German Environment Agency, Wörlitzer Platz 1, 06844 Dessau-Roßlau, Germany 3 University of Duisburg-Essen, Centre for Water and Environmental Research (ZWU), Universitätsstr. 3, 45141 Essen, Germany Corresponding author: Till-Hendrik Macher ([email protected]) Academic editor: Pieter Boets | Received 26 March 2021 | Accepted 10 June 2021 | Published 13 July 2021 Abstract Fast, reliable, and comprehensive biodiversity monitoring data are needed for environmental decision making and management. Recent work on fish environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding shows that aquatic diversity can be captured fast, reliably, and non-invasively at moderate costs. Because water in a catchment flows to the lowest point in the landscape, often a stream, it can col- lect traces of terrestrial species via surface or subsurface runoff along its way or when specimens come into direct contact with water (e.g., when drinking). Thus, fish eDNA metabarcoding data can provide information on fish but also on other vertebrate species that live in riparian habitats. This additional data may offer a much more comprehensive approach for assessing vertebrate diversity at no additional costs. Studies on how the sampling strategy affects species detection especially of stream-associated communities, however, are scarce. We therefore performed an analysis on the effects of biological replication on both fish as well as (semi-)terrestrial species detection. -

Identification of Priority Areas for the Conservation of Stream Fish Assemblages: Implications for River Management in France A

Identification of Priority Areas for the Conservation of Stream Fish Assemblages: Implications for River Management in France A. Maire, P. Laffaille, J.F. Maire, L. Buisson To cite this version: A. Maire, P. Laffaille, J.F. Maire, L. Buisson. Identification of Priority Areas for the Conservation of Stream Fish Assemblages: Implications for River Management in France. River Research and Applications, Wiley, 2016, 33 (4), pp.524-537. 10.1002/rra.3107. hal-01426354 HAL Id: hal-01426354 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01426354 Submitted on 2 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License IDENTIFICATION OF PRIORITY AREAS FOR THE CONSERVATION OF STREAM FISH ASSEMBLAGES: IMPLICATIONS FOR RIVER MANAGEMENT IN FRANCE A. MAIREa*,†, P. LAFFAILLEb,c, J.-F. MAIREd AND L. BUISSONb,e a Irstea; UR HYAX, Pôle Onema-Irstea Hydroécologie des plans d’eau; Centre d’Aix-en-Provence, Aix-en-Provence, France b CNRS; UMR 5245 EcoLab, (Laboratoire Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Environnement), Toulouse, France c Université de Toulouse, INP, UPS; EcoLab; ENSAT, Castanet Tolosan, France d ONERA, The French Aerospace Lab Composites Department, Châtillon, France e Université de Toulouse, INP, UPS; EcoLab, Toulouse, France ABSTRACT Financial and human resources allocated to biodiversity conservation are often limited, making it impossible to protect all natural places, and priority areas for protection must be identified. -

The Whitefin Gudgeon Romanogobio Belingi New for the Netherlands

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Lauterbornia Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 2005_55 Autor(en)/Author(s): Soes Menno, Spaans Piet J., Veenvliet Paul Artikel/Article: The Whitefin gudgeon Romanogobio belingi new for the Netherlands. 141-144 ©Erik Mauch Verlag, Dinkelscherben, Deutschland,141 Download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Lauterbornia 55: 141-144, D-86424 Dinkelscherben, 2005-08-19 The Whitefin gudgeon Romanogobio belingi new for The Netherlands D. M. Soes, P. J. Spaans and P.Veenvliet With 2 figures Keywords: Romanogobio, Pisces, Waal, Rhine, The Netherlands, first record Schlagwörter: Romanogobio, Pisces, Waal, Rhein, Niederlande, Erstfund The whitefin gudgeon Romanogobia belingi (Lukasch, 1933) is recorded for he first time from The Netherlands 1 Introduction In the past years the fish fauna of the Dutch rivers belonging to the River Rhine system has been altered significantly. Species introduced to the Rhine system, such as Vimba (Vimba vimba), Asp (Aspius aspius) and Danube bream (Abramis sapa) are nowadays found in the Dutch waters (De Nie, 1996; Frey hof, et al., 2000; Van Emmerik, 2003). One Danubian species, the Tubenose goby (Proterorhinus marmoratus), invaded the River Rhine system via the Main-Danube-Canal and made it up to the Netherlands (Winter, 2002). Several other species of gobies are thought to follow (Freyhof, 2003). Already in 1998, Freyhof reported on another species in the River Rhine, which could be expected to occur in the Netherlands. This species, the White fin gudgeon (Romanogobio belingi (Lukasch, 1933), was found to be common and widespread in German parts of the River Rhine. -

Fish, Crustaceans, Molluscs, Etc Capture Production by Species Items Europe

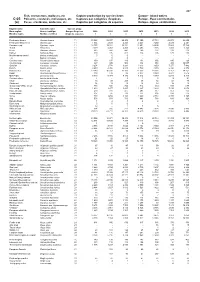

467 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc Capture production by species items Europe - Inland waters C-05 Poissons, crustacés, mollusques, etc Captures par catégories d'espèces Europe - Eaux continentales (a) Peces, crustáceos, moluscos, etc Capturas por categorías de especies Europa - Aguas continentales English name Scientific name Species group Nom anglais Nom scientifique Groupe d'espèces 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Nombre inglés Nombre científico Grupo de especies t t t t t t t Freshwater bream Abramis brama 11 33 823 35 937 29 408 31 390 27 734 28 978 28 655 Freshwater breams nei Abramis spp 11 1 934 2 029 2 223 2 243 3 250 2 439 2 241 Common carp Cyprinus carpio 11 12 755 13 381 13 351 13 951 14 695 17 883 17 729 Tench Tinca tinca 11 3 019 4 053 2 455 2 253 1 686 1 491 1 328 Bleak Alburnus alburnus 11 682 547 441 269 231 213 219 Barbel Barbus barbus 11 300 195 412 224 205 170 188 Mediterranean barbel Barbus meridionalis 11 0 0 0 - - - - ...A Barbus cyclolepis 11 ... 0 0 - - - - Common nase Chondrostoma nasus 11 159 137 189 134 156 195 123 Crucian carp Carassius carassius 11 367 345 506 332 351 305 19 057 Goldfish Carassius auratus 11 3 254 2 778 3 293 3 613 3 653 7 277 7 482 Roach Rutilus rutilus 11 4 259 4 956 4 915 3 789 3 670 6 328 6 378 Roaches nei Rutilus spp 11 13 243 16 331 17 160 17 553 18 361 17 757 14 151 Rudd Scardinius erythrophthalmus 11 108 139 96 8 077 9 380 8 977 7 516 Orfe(=Ide) Leuciscus idus 11 5 040 5 374 5 330 4 812 5 979 6 240 5 316 Common dace Leuciscus leuciscus 11 4 .. -

The Black Sea Region — Shores and Delta

Black Sea region. page 1 European Environment Agency Europe’s biodiversity — biogeographical regions and seas Biogeographical regions in Europe The Black Sea Region — shores and delta Original contributions from ETC/NPB: Sophie Condé, Dominique Richard (coordinators) Nathalie Liamine (editor) Anne-Sophie Leclère (data collection and processing) Barbara Sotolargo (drafting) Ulla Pinborg (final co-editor) Map production: UNEP/GRID Warsaw (final production) Project manager: Tor-Björn Larsson, EEA ZooBoTech HB, Sweden, Linus Svensson (final edition) Black Sea region. page 2 Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 1. What are the main characteristics and trends of the Black Sea biogeographical region? ..................................................................................... 3 1.1 General characteristics.............................................................................. 3 1.1.1 Extent and limitations ............................................................................ 3 1.1.2 Geomorphological and topography ........................................................... 3 1.1.3 Soils .................................................................................................... 4 1.1.4 Climate ................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Present biodiversity status and trends: habitats, fauna and flora ............. 5 1.2.1 Habitats .............................................................................................. -

And Perca Fluviatilis

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Using Rutilus rutilus (L.) and Perca fluviatilis (L.) as Bioindicators of the Environmental Condition and Human Health: Lake Ła ´nskie,Poland Joanna Łuczy ´nska 1,* , Beata Paszczyk 1, Marek Jan Łuczy ´nski 2, Monika Kowalska-Góralska 3 , Joanna Nowosad 4 and Dariusz Kucharczyk 4 1 Chair of Commodity and Food Analysis, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, ul. Plac Cieszy´nski1, 10-726 Olsztyn, Poland; [email protected] 2 The Stanisław Sakowicz Inland Fisheries Institute in Olsztyn, ul. Oczapowskiego 10, 10-719 Olsztyn, Poland; mj.luczynski@infish.com.pl 3 Department of Limnology and Fishery, Institute of Animal Breeding, Faculty of Biology and Animal Science, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, ul. J. Chełmo´nskiego38 c, 51-630 Wrocław, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Ichthyology and Aquaculture, Warmia and Mazury University, Al. Warszawska 117A, 10-701 Olsztyn, Poland; [email protected] (J.N.); [email protected] (D.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-89523-4165 Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 19 October 2020 Abstract: The aim of this study was to determine the mercury content and fatty acids profile in roach (Rutilus rutilus L.) and European perch (Perca fluviatilis L.) from Lake Ła´nskie(Poland). Mercury content was higher in the muscles than other organs in both species (p < 0.05). Mercury accumulates along the food chain of the lake’s ecosystem. The value of the bioconcentration factor (BCF) indicated that Hg had accumulated in the highest amounts in muscles and in the other organs as follows: muscles > liver > gills > gonads. -

AHNELT H. 2008. Bestimmungsschlüssel Für Die In

Ahnelt H. 2008 Bestimmungsschlüssel 1 BESTIMMUNGSSCHLÜSSEL FÜR DIE IN ÖSTERREICH VORKOMMENDEN FISCHE HARALD AHNELT Department für Theoretische Biologie, Fakultät für Lebenswissenschaften, Universität Wien, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Wien [email protected] Online: 10 September 2008 Zitiervorschlag: Ahnelt H. 2008 Bestimmungsschlüssel für die in Österreich vorkommenden Fische. http://homepage.univie.ac.at/harald.ahnelt/Harald_Ahnelts_Homepage/Publications.html [Download-Datum] Bestimmungsschlüssel heimischer Fische Dieser Bestimmungsschlüssel ist für die Fischarten Österreichs ausgelegt. Merkmale und Merkmalskombinationen können daher bei Anwendung auf Fische anderer Länder zu nicht korrekten Ergebnissen führen. Identification key for Austrian freshwater fishes This identification key should only be used for fishes from Austrian freshwaters. This key will possibly not work for fishes from other European countries. Nobody is perfect – schon gar nicht ein Bestimmungsschlüssel. Ein Bestimmungsschlüssel baut auf charakteristischen Merkmalen auf, er vereinfacht und kann keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit erheben. Auch dieser Bestimmungsschlüssel ist nur ein Versuch ein komplexes System in einen übersichtliche Form zu bringen. Die Natur sieht aber oft anders aus. Die Bandbreite an Merkmalen ist bei vielen Arten groß. Manche Populationen sind an unterschiedliche Umweltbedingungen angepasst und bilden unterscheidbare ökologische Formen. Andere Populationen sind isoliert und einige davon sind systematisch noch ungenügend erforscht. Möglicherweise taucht ja in Österreich noch die eine oder andere neue Art auf. Sollte es einmal nicht passen, oder wenn sich ein Fehler eingeschlichen hat, ersuche ich um Information - [email protected] oder unter obiger Adresse. Verbesserungsvorschläge und Ergänzungen sind willkommen. Ahnelt H. 2008 Bestimmungsschlüssel 2 Einleitung 1858 erschien das Buch „Die Süßwasserfische der Österreichischen Monarchie mit Rücksicht auf die angrenzenden Länder“, verfasst von den Österreichern Johann Jakob Heckel und Rudolf Kner. -

Growth, the Length-Weight Relationship, and Reproduction in Vimba (Vimba Vimba L

Turk J Zool 2011; 35(1): 87-96 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-0901-16 Growth, the length-weight relationship, and reproduction in vimba (Vimba vimba L. 1758) sampled from an oligo-mesotrophic lake in northwest Anatolia (Turkey) Hacer OKGERMAN1,*, Mahmut ELP2, Cumhur H. YARDIMCI1 1İstanbul University, Fisheries Faculty, Freshwater Biology Department, İstanbul - TURKEY 2Yüzüncü Yıl University, Agriculture Faculty, Van - TURKEY Received: 13.01.2009 Abstract: The growth parameters and reproduction period in vimba (Vimba vimba L. 1758) sampled from Sapanca Lake were determined monthly between September 2003 and July 2004. The 335 vimba specimens caught ranged in age from 2+ to 6+ years, and the majority of the samples consisted of individuals of the 4+-year-old age group. The length-weight relationship was estimated to be W = 0.0084 FL3.1797±0.0035 for males (r2 = 0.94, P < 0.05) and W = 0.0089 FL3.1572±0.0033 for females (r2 = 0.93, P < 0.05). Regression coefficients for sex were significant (t-test, P < 0.05). The slope (b) significantly differed (ANCOVA, P < 0.05) between months. The fact that the b values for male and female vimba specimens differed from 3.0 indicates that there was positive allometric growth. The von Bertalanffy equation was determined using Lt = 28.940 (1-exp {-0.123[t+2.193]}), ∅’: 2.030, (r = 0.999) for males and Lt = 24.708 [1-exp {-0.205[t+1.464]}), ∅’: 2.097, (r = 0.999) for females. The sex ratio was 1:1.86 (χ2; P < 0.05). The spawning period of vimba began at the end of April and continued until the beginning of July; the water temperature during this period was between 14.8 and 25.9 °C. -

Applied Freshwater Fish Biology an Introduction to Methods of Research and Management

How to preserve and how to exploit natural populations to be sustained for the future. Plain questions without equally plain answers Applied freshwater fish biology An introduction to methods of research and management Arne N. Linløkken, ass. professor Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences Arne N. 1 CONTENT INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Prehistory and evolution ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Short on construction and function ......................................................................................................................... 4 Morphology ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Anatomy and physiology .................................................................................................................................... 5 European freshwater fish species ............................................................................................................................ 6 Immigration and distribution of freshwater fish in western Scandinavia ........................................................... 7 Western immigrants ........................................................................................................................ 8 -

Reproduction Characteristics of the Vimba Vimba Persa (Pallas, 1811), in Coastal Waters of the Caspian Sea

Reproduction characteristics of the Vimba vimba persa (Pallas, 1811), in coastal waters of the Caspian Sea Item Type article Authors Chaichi, A.R.; Vosoughi, G.H.; Kaymaram, F.; Jamili, S.; Fazli, H. Download date 28/09/2021 21:28:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/37234 Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 10(4) 585-595 2011 Reproduction characteristics of the Vimba vimba persa (Pallas, 1811), in coastal waters of the Caspian Sea Chaichi A. R. 1*; Vosoughi G. h.1; Kaymaram F.2; Jamili S.1,2; Fazli H.3 Received: October 2010 Accepted: March 2011 Abstract Some reproduction characteristics of the Caspian Vimba, Vimba vimba persa, were studied from Oct. 2008 to Sep. 2009 in coastal waters of the Caspian Sea (Mazandaran province). 994 specimens were monthly collected from 6 fish landing sites of Ramsar, Tonekabon, Chalus, Mahmood Abad, Sari and Behshahr. The fecundity was measured using 92 specimens. This species was found to have more abundance in spring (especially April and May). The samples composed of 397(42.6%) male, 537(57.4%) female; the sex ratio was M: F = 1:1.35. The advanced stages of maturity (4th & 5th) were found in April and May. The highest Gonadosomatic Index in females was in May and the lowest one was in July. The average of absolute and relative fecundities was 17198±7710 and 171.85±48.8, respectively. Keywords: Caspian Vimba, Vimba vimba persa, Fecundity, GSI, Sex ratio, Caspian Sea Downloaded from jifro.ir at 16:34 +0330 on Monday February 12th 2018 ____________________ 1- Graduate School of Marine Science & Technology, Department of Marine Biology, Science and Research, Islamic Azad University, Tehran- Iran.