Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development Potentials in Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Prosperity Initiative

USAID/GEORGIA DO2: Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth October 1, 2011 – September 31, 2012 Gagra Municipal (regional) Infrastructure Development (MID) ABKHAZIA # Municipality Region Project Title Gudauta Rehabilitation of Roads 1 Mtskheta 3.852 km; 11 streets : Mtskheta- : Mtanee Rehabilitation of Roads SOKHUMI : : 1$Mestia : 2 Dushet 2.240 km; 7 streets :: : ::: Rehabilitation of Pushkin Gulripshi : 3 Gori street 0.92 km : Chazhashi B l a c k S e a :%, Rehabilitaion of Gorijvari : 4 Gori Shida Kartli road 1.45 km : Lentekhi Rehabilitation of Nationwide Projects: Ochamchire SAMEGRELO- 5 Kareli Sagholasheni-Dvani 12 km : Highway - DCA Basisbank ZEMO SVANETI RACHA-LECHKHUMI rehabilitaiosn Roads in Oni Etseri - DCA Bank Republic Lia*#*# 6 Oni 2.452 km, 5 streets *#Sachino : KVEMO SVANETI Stepantsminda - DCA Alliance Group 1$ Gali *#Mukhuri Tsageri Shatili %, Racha- *#1$ Tsalenjikha Abari Rehabilitation of Headwork Khvanchkara #0#0 Lechkhumi - DCA Crystal Obuji*#*# *#Khabume # 7 Oni of Drinking Water on Oni for Nakipu 0 Likheti 3 400 individuals - Black Sea Regional Transmission ZUGDIDI1$ *# Chkhorotsku1$*# ]^!( Oni Planning Project (Phase 2) Chitatskaro 1$!( Letsurtsume Bareuli #0 - Georgia Education Management Project (EMP) Akhalkhibula AMBROLAURI %,Tsaishi ]^!( *#Lesichine Martvili - Georgia Primary Education Project (G-Pried) MTSKHETA- Khamiskuri%, Kheta Shua*#Zana 1$ - GNEWRC Partnership Program %, Khorshi Perevi SOUTH MTIANETI Khobi *# *#Eki Khoni Tskaltubo Khresili Tkibuli#0 #0 - HICD Plus #0 ]^1$ OSSETIA 1$ 1$!( Menji *#Dzveli -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

FÁK Állomáskódok

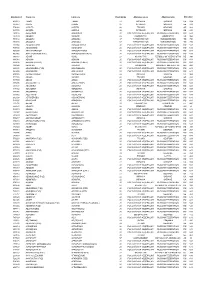

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Ethnobiology of Georgia

SHOTA TUSTAVELI ZAAL KIKVIDZE NATIONAL SCIENCE FUNDATION ILIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS ETHNOBIOLOGY OF GEORGIA ISBN 978-9941-18-350-8 Tbilisi 2020 Ethnobiology of Georgia 2020 Zaal Kikvidze Preface My full-time dedication to ethnobiology started in 2012, since when it has never failed to fascinate me. Ethnobiology is a relatively young science with many blank areas still in its landscape, which is, perhaps, good motivation to write a synthetic text aimed at bridging the existing gaps. At this stage, however, an exhaustive representation of materials relevant to the ethnobiology of Georgia would be an insurmountable task for one author. My goal, rather, is to provide students and researchers with an introduction to my country’s ethnobiology. This book, therefore, is about the key traditions that have developed over a long history of interactions between humans and nature in Georgia, as documented by modern ethnobiologists. Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my colleagues – Rainer Bussmann, Narel Paniagua Zambrana, David Kikodze and Shalva Sikharulidze for the exciting and fruitful discussions about ethnobiology, and their encouragement for pushing forth this project. Rainer Bussmann read the early draft of this text and I am grateful for his valuable comments. Special thanks are due to Jana Ekhvaia, for her crucial contribution as project coordinator and I greatly appreciate the constant support from the staff and administration of Ilia State University. Finally, I am indebted to my fairy wordmother, Kate Hughes whose help was indispensable at the later stages of preparation of this manuscript. 2 Table of contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. A brief introduction to ethnobiology...................................................................................... -

ELKANA/FAO Workshop on EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

ELKANA/FAO Workshop on EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT AMONG AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH, EXTENSION AND FARMERS FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN GEORGIA organized by the Biological Farming Association “ELKANA”, Georgia and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 1-3 February 2005 Tbilisi, Georgia TABLE OF CONTENT EXECUT IVE S UMM ARY ...................................................................................................... 4 ACKNO WLEDG EM ENTS ..................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND................................................................... 7 2. PRESENTATIONS........................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Participants............................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Programme of the workshop .................................................................................. 7 2.3 Summary of presentations and discussions............................................................ 9 2.4 SWOT Analysis.................................................................................................... 11 2.5 Developing ideas for cooperation......................................................................... 13 2.6 Session A. Drafting a project outline by group representatives........................... 13 2.7 Conclusions and Recommendations of the Workshop........................................ -

Anatolian Rivers Between East and West

Anatolian Rivers between East and West: Axes and Frontiers Geographical, economical and cultural aspects of the human-environment interactions between the Kızılırmak and Tigris Rivers in ancient times A series of three Workshops * First Workshop The Connectivity of Rivers Bilkent University Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture & Faculty of Humanities and Letters Ankara 18th November 2016 ABSTRACTS Second Workshop, 4th – 7th May 2017, at the State University Shota Rustaveli, Batumi. The Exploitation of the Economic Resources of Rivers. Third Workshop, 28th – October 1st September 2017, at the French Institute for Anatolian Studies, Istanbul. The Cultural Aspects of Rivers. Frontier Rivers between Asia and Europe Anca Dan (Paris, CNRS-ENS, [email protected]) The concept of « frontier », the water resources and the extension of Europe/Asia are currently topics of debates to which ancient historians and archaeologists can bring their contribution. The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the watercourses which played a part in the mental construction of the inhabited world, in its division between West and East and, more precisely, between Europe and Asia. The paper is organized in three parts: the first is an inventory of the watercourses which have been considered, at some point in history, as dividing lines between Europe and Asia; the second part is an attempt to explain the need of dividing the inhabited world by streams; the third part assesses the impact of this mental construct on the reality of a river, which is normally at the same time an obstacle and a spine in the mental organization of a space. -

17. Preliminary Data on the Studies of Alosa Immaculate in Romanian

Scientific Annals of the Danube Delta Institute Tulcea, România Vol. 22 2016 pp. 141-148 Preliminary Data on the Studies of Alosa immaculate in Romanian marine waters 17. ȚIGANOV George1, NĂVODARU Ion1, CERNIȘENCU Irina1, NĂSTASE Aurel1, MAXIMOV Valodia2, OPREA Lucian3 1 - Danube Delta National Institute for Research and Development: 165 Babadag street, Tulcea - 820112, Romania; e-mail: [email protected] 2 - National Institute for Marine Research and Development “Grigore Antipa”: 300 Blvd Mamaia, Constanta - 900581, Romania 3- "Lower Danube" University of Galati, Faculty of Food Science and Engineering, 111 Domnească Street, Galați, 800201, Romania Address of author responsible for correspondence: ȚIGANOV George, Danube Delta National Institute for Research and Development: Babadag street, No. 165, Tulcea - 820112, Romania; email: [email protected] bstract: Danube shad is a fish with high economic and socio-cultural value for the human communities established in the Danubian-Pontic space. In Romania, shad fishery has a market Avalue of about 1.5 million euro, with average annual catches of 200-500 tonnes. Biological material was collected during research surveys organized along the Black Sea coast, in 2012-2013, in spring season (March, April), summer (June, July) and autumn (September). Experimental fishing was done with fishing gillnets. Demographic structure of Alosa immaculata consists of generations of 2-5 years, dominated by generations of 3 to 4 years. The aim of this paper is to provide recent data regarding Alosa immaculata population along the Black Sea Coast consideribg that its biology is less known. Keywords: Danube shad, experimental fishing, Alosa immaculata, Black Sea. INTRODUCTION Genus Alosa is represented by several species, the most important being distributed in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, Black Sea and Caspian Sea. -

Abhazya/Gürcistan: Tarih – Siyaset – Kültür

TÜR L Ü K – CEMAL GAMAKHARİA LİA AKHALADZE T ASE Y Sİ – H ARİ T : AN T S Cİ R A/GÜ Y ABHAZ ZE D İA AKHALA İA L İA İA R ABHAZYA/GÜRCİSTAN: ,6%1 978-9941-461-51-4 L GAMAKHA L TARİH – SİYASET – KÜLTÜR CEMA 9 7 8 9 9 4 1 4 6 1 5 1 4 CEMAL GAMAKHARİ A Lİ A AKHALADZE ABHAZYA/GÜRCİ STAN: TARİ H – Sİ YASET – KÜLTÜR Tiflis - İ stanbul 2016 UDC (uak) 94+32+008)(479.224) G-16 Yayın Kurulu: Teimuraz Mjavia (Editör), Prof. Dr. Roin Kavrelişvili, Prof. Dr. Erdoğan Altınkaynak, Prof. Dr. Rozeta Gujejiani, Giorgi Iremadze. Gürcüce’den Türkçe’ye Prof. Dr. Roin Kavrelişvili tarafından tercüme edil- miştir. Bu kitapta Gürcistan’ın Özerk Cumhuriyeti Abhazya’nın etno-politik tarihi üzerine dikkat çekilmiş ve bu bölgede bulunan kadim Hıristiyan kül- türüne ait ana esaslar ile ilgili genel görüşler ortaya konulmuştur. Etnik, siyasi ve kültürel açıdan bakıldığında, Abhazya’nın günümüzde sahip olduğu toprakların, tarihin eski dönemlerinden bu yana Gürcü bölgesi olduğu ve bölgede gerçekleşen demografik değişiklilerin ancak Orta Çağın son dönemlerinde gerçekleştiği anlaşılmaktadır. Bu kitabın yazarları 1992 – 1993 yılları arasında Rusya tarafından Gürcistan’a karşı girişilen hibrid savaşlardan ve 2008’de gerçekleştirilen açık saldırganlıktan bahsetmektedirler. Burada, savaştan sonra meydana gelen insani felaketler betimlenmiş, Abhazya’nın işgali ile Avrupa- Atlantik sahasına karşı yapılan hukuksuz jeopolitik gelişmeler anlatılmış ve uluslararası kuruluşların katılımıyla Abhazya’da sürekli ortaya çıkan çatışmaların barışçıl bir yol ile çözülmesinin gerekliliği üzerinde durulmuştur. Düzenleme Levan Titmeria ISBN 978-9941-461-51-4 İçindekiler Giriş (Prof. Dr. Cemal Gamakharia) ..................................... 5 1. -

Three New Species of Alburnoides (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) from Euphrates River, Eastern Anatolia, Turkey

Zootaxa 3754 (2): 101–116 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3754.2.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:33DCB673-BC7C-4DB2-84CE-5AC5C6AD2052 Three new species of Alburnoides (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) from Euphrates River, Eastern Anatolia, Turkey DAVUT TURAN1,3, CÜNEYT KAYA1, F. GÜLER EKMEKÇİ2 & ESRA DOĞAN1 1Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University, Faculty of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 53100 Rize, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Hacettepe University, Beytepe Campus, 06800 Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Three new species of Alburnoides, Alburnoides emineae sp. n., Alburnoides velioglui sp. n., Alburnoides recepi sp. n., are described from the Euphrates River drainages (Persian Gulf basin) in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. Alburnoides emineae, from Beyazsu Stream (south-eastern Euphrates River drainage), is distinguished from all species of Alburnoides in Turkey and adjacent regions by a combination of the following characters (none unique to the species): a well developed ventral keel between pelvic and anal fins, commonly scaleless or very rarely 1–2 scales covering the anterior portion of the keel; a deep body (depth at dorsal-fin origin 31–36% SL); 37–43 + 1–2 lateral-line scales, 13½–15½ branched anal-fin rays; number of total vertebrae 41–42, modally 41, comprising 20–21 abdominal and 20–21 caudal vertebrae. Alburnoides velioglui, from Sırlı, Karasu, Divriği and Sultansuyu streams (northern and northeastern Euphrates River drainages), is distinguished by a poorly developed ventral keel, completely scaled; a moderately deep body (depth at dorsal-fin origin 24–29% SL); 45–53 + 1–2 lateral-line scales, 11½ –13½ branched anal-fin rays; number of total vertebrae 41–42, modally 42, comprising 20–22 abdominal and 20–21 caudal vertebrae. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 66462-GE PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 25.8 MILLION Public Disclosure Authorized (US$40.00 MILLION EQUIVALENT) AND A PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$30 MILLION TO GEORGIA Public Disclosure Authorized FOR THE SECOND SECONDARY AND LOCAL ROADS PROJECT (SLRP-II) FEBRUARY 21, 2012 Sustainable Development Department South Caucasus Country Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 1, 2012) Currency Unit = Georgian Lari (GEL) GEL 1.66 = US$ 1.00 US$1.551 = SDR 1.00 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AADT Average Annual Daily Traffic MCC Millennium Challenge Corporation ADB Asian Development Bank MENR Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources CPS Country Partnership Strategy MESD Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development EA Environmental Assessment MRDI Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure EIB European Investment Bank NBG National Bank of Georgia EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return NCB National Competitive Bidding EMP Environmental Management Plan NPV Net Present Value ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ORAF Operational Risk Assessment Framework FA Financing Agreement PAD -

Abkhazia: Deepening Dependence

ABKHAZIA: DEEPENING DEPENDENCE Europe Report N°202 – 26 February 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. RECOGNITION’S TANGIBLE EFFECTS ................................................................... 2 A. RUSSIA’S POST-2008 WAR MILITARY BUILD-UP IN ABKHAZIA ...................................................3 B. ECONOMIC ASPECTS ....................................................................................................................5 1. Dependence on Russian financial aid and investment .................................................................5 2. Tourism potential.........................................................................................................................6 3. The 2014 Sochi Olympics............................................................................................................7 III. LIFE IN ABKHAZIA........................................................................................................ 8 A. POPULATION AND CITIZENS .........................................................................................................8 B. THE 2009 PRESIDENTIAL POLL ..................................................................................................10 C. EXTERNAL RELATIONS ..............................................................................................................11 -

Glaciers Change Over the Last Century, Caucasus Mountains, Georgia

1 Glaciers change over the last century, Caucasus Mountains, 2 Georgia, observed by the old topographical maps, Landsat 3 and ASTER satellite imagery 4 5 L. G. Tielidze 6 7 Department of Geomorphology, Vakhushti Bagrationi Institute of Geography, Ivane 8 Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, 6 Tamarashvili st. Tbilisi 0177, Georgia 9 10 Correspondence to: L. G. Tielidze ([email protected]) 11 12 13 Abstract 14 15 The study of glaciers in the Caucasus began in the first quarter of the 18th century. The 16 first data on glaciers can be found in the works of great Georgian scientist Vakhushti 17 Bagrationi. After almost hundred years the foreign scientists began to describe the 18 glaciers of Georgia. Information about the glaciers of Georgia can be found in the 19 works of W. Abich, D. Freshfield, G. Radde, N. Dinik, I. Rashevskiy, A. Reinhardt etc. The 20 first statistical information about the glaciers of Georgia are found in the catalog of the 21 Caucasus glaciers compiled by K. Podozerskiy in 1911. Then, in 1960s the large-scale 22 (1 : 25 000, 1 : 50 000) topographic maps were published, which were compiled in 23 1955–1960 on the basis of the airphotos. On the basis of the mentioned maps R. 24 Gobejishvili gave quite detailed statistical information about the glaciers of Georgia. Then 25 in 1975 the results of glaciers inventory of the former USSR was published, where the 26 statistical information about the glaciers of Georgia was obtained on the basis of the 27 almost same time (1955-1957) aerial images.